Towards a new model of ageing together in the UK:The Analysis of New Ground Cohousing

Abstract

Cohousing is an alternative type of collaborative housing development which started in Denmark in the late 1960s. According to Graciano (2011: 169), the aim of this “new” typology is to create a sense of neighborliness and belonging for residents. In this type of community, residents not only share common facilities but also share evening meals despite having their own private homes. As the number of cohousing communities is increasing in the world, in some countries such as the United Kingdom, the pace of this development is slow due to the traditional values and habits. However, the New Ground Cohousing in London faced this cultural blockage and became the UK’s first ever senior cohousing community. In this essay, the New Ground Cohousing in High Barnet will be used to discuss how people gather together in order to live harmoniously in this community building. Some key points such as a sense of community, sense of home, and a blend of privacy and communal life will be investigated in this case study. As cohousing provides an environment that considers various factors such as social community, private living space and community interactions within common facilities, it grants itself open grounds for analytical observation and further investigation. In this essay, the information will be collected from related books, articles, and websites alongside the analysis of some videos proposed by the OWCH and Urban Design Group.

Keywords: cohousing; the New Ground Cohousing; older people; community; privacy

Contents

List of figures 5

Introduction 6

Part I_ Literature Review

1.1. Cohousing 8

1.2. Theory and definition of sense of community 9

1.2.1. Membership 9

1.2.2. Influence 9

1.2.3. Reinforcement (integration and fulfillment of needs) 9

1.2.4. A shared emotional connection 10

1.3. Theory and definition of sense of home 10

1.3.1. Use of the term home 10

1.3.2. Home is more than a physical environment 10

Part II_ Case Study

2.1. The New Ground Cohousing 12

2.2. Sense of community 14

2.3. Sense of home 16

2.3.1. Centrality 16

2.3.2. Continuity 16

2.3.3. Privacy 17

2.3.4. Self- expression and personal identity 17

2.4.5. Social relationship 18

2.4. A blend of privacy and communal life 18

2.4.1. Collaborative design 19

2.4.2. Analysis of the design 20

2.4.3. Privacy and communal life in the New Ground cohousing 20

Conclusion 21

Bibliography and references 23

List of figures

Figure 1: Pollard Thomas Edward (2016), The New Ground Cohousing [image]. Available from http://pollardthomasedwards.co.uk/project/owch/ [Accessed 6 January 2018]

Figure 2: Mairs, J. (2016), Ground Floor [image]. Available from https://www.dezeen.com/2016/12/09/pollard-thomas-edwards-architecture-first-older-co-housing-scheme-owch-uk/ [Accessed 6 January 2018]

Figure 3: Mairs, J. (2016), First Floor [image]. Available from https://www.dezeen.com/2016/12/09/pollard-thomas-edwards-architecture-first-older-co-housing-scheme-owch-uk/ [Accessed 6 January 2018]

Figure 4: Mairs, J. (2016), Second Floor [image]. Available from https://www.dezeen.com/2016/12/09/pollard-thomas-edwards-architecture-first-older-co-housing-scheme-owch-uk/ [Accessed 6 January 2018]

Figure 5: Crocker, T. (2017), Apartments are generous spaces filled with light that have already acquired the feel of their occupants [image]. Available from https://www.ribaj.com/buildings/new-ground [Accessed 8 January 2018]

Figure 6: Crocker, T. (2017), Inside, apartments feel personal sand sheltered [image]. Available from https://www.ribaj.com/buildings/new-ground [Accessed 8 January 2018]

Figure 7: Devlin, P. (2017), Concept diagram mapping out public and private routes and boundaries with a co-house at center [image]. Available from https://www.ribaj.com/buildings/new-ground [Accessed 8 January 2018]

Figure 8: Devlin, P. (2017), The housing is tied together by the gardens [image]. Available from https://www.ribaj.com/buildings/new-ground [Accessed 8 January 2018]

Figure 9: Devlin, P. edited by author (2017), The private, social, and public spaces of the New Ground Cohousing [image]. Available from https://www.ribaj.com/buildings/new-ground [Accessed 8 January 2018]

Introduction

In recent years, there has been considerable attention in the ways in which housing affects the quality of people’s lives. Housing plays an important role in forming the quality of life for all people, particularly elderly people who spend most of their time at home (75% as mentioned by Moose & Lawton, 1982 cited in Zaff and Devlin, 1998). Poor housing standards could potentially result in an increase in mental health diseases. According to Mental Health Foundation (2016), mental health diseases are increasing not only in the UK but also around the world and they also estimated that in every six people, one of them has mental health problems such as depression which is primarily caused by social isolation. As a result, some alternative housing options such as cohousing were developed to fulfill the need of communication and mitigate the isolation and loneliness which often experienced by society.

The idea of living in a community building such as cohousing came from a group of families in Denmark in the late 1960s. They were looking for a place for their children to be looked after and they also wanted to share the preparation of their food because both mother and father had work commitments. After a few years, the first cohousing community building was built in Denmark in 1972 by 27 families who were interested in a greater sense of community (McCamant and Durrett, 2011). Now, cohousing has become attractive to different types of families such as single parents, young people and retired couples.

The term cohousing has originally come from the translation of the Danish word “Bofaellesskaber” which means living communities in English (ScottHanson and ScottHanson, 2005). Some definitions were suggested for the term cohousing in the early 90th century. Fromm (1991) defined cohousing as “collaborated communities”, “central living” and “housing with shared facilities” while Frank and Ahrentzen (1989) propose a definition as “housing that features spaces and facilities for joint use by all residents who also maintain their independent living” (cited in Choi, 2004, p 1190) . In this essay, the main focus is on cohousing communities who live together and share facilities in the cohousing scheme. It is also worth mentioning the definition of “community” in cohousing as there are different interpretations for the word “community”. The first American sociologist who suggested a definition for the word “community” was Robert Park (Lyon and Driskell, 2011). According to Park (1936), “ the essential characteristics of a community, so convinced, are those of: (1) a population territorially organized, (2) more or less completely rooted in the soil it occupies, (3) its individual units living in relationship of mutual interdependence…” (cited in Lyon and Driskell, 2011, p 4). After less than twenty years, George Hillery defined a community “as people in a specific area who share common ties and interact with one another” (Lyon and Driskell, 2011, p 5). Lyon and Driskell (2011) believed that there is still no accurate definition of the term community. They noted that in order to understand community, studies should take into account of the people who are living within the community, placing special focus on the quality and type of their interaction. The origins of community theory came from a German sociologist, Ferdinand Tonnies. He introduced the term Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft which is translated as Community and Society. He considered the type of relationship which existed in an extended family in a rural village as Gemeinschaft (community) in contrast of Gesellschaft (society) found in modern and capitalist states (Tonnies and Loomis, 1957). He explained that Gemeinschaft is formed by social belonging and a strong identification while Gesellschaft includes an emotional disengagement and individualism. According to Tonnies’ theory, it could be assumed that cohousing communities are probably the nostalgia of rural villages because as McCamant and Durrett (2011) mentioned it has many positive effects of traditional rural villages in the twenty-first-century life.

Community and cohousing are the keywords in this essay because cohousing is more than just a physical design. According to Brenton (2017, p 3), it is the “social architecture that makes the place stand out”. In addition, the sociability and the interactions happen within the community could be affected by many factors such as the member of the community and the design of the cohousing. The objectives here are to analyze how people gather together and communicate in this type of community buildings, how cohousing as a typology could generate a sense of community and a sense of home and how the privacy and sociability are blended together. This study takes the form of a case-study of the New Ground Cohousing using journal articles, books, videos and sketch drawings. In addition, attemps were made to visit the site and interview with some of the residents, however, due to the high numbers of past visits the site had received in recent months, further public access was not allowed in the new Ground Cohousing.

Part I

1. Literature Review

1.1. Cohousing

Cohousing is an alternative typology of collaborative housing development designed to create a sense of neighborliness and belonging for residents (Garciano, 2011). While these types of community buildings are different in size, ownership, design and location, they are designed intentionally for the concept of sharing the same characteristics such as evening meals and common facilities. Residents of cohousing also have their own kitchen in their private houses as an option to have their privacy whenever they choose. Having common dinners is a good opportunity for members to get to know each other and according to Scotthanson and Scotthanson (2005, p 13) “together they create a culture of value around meals”. Other common facilities such as a guest room for the events and a children’s playroom make it easier for them to communicate and interact.

Cohousing could be suitable for anyone who has a desire for community, according to the UK Cohousing Network. However, a survey of residents of cohousing in North America demonstrates that the age of the residents is usually between the early thirties and retirement age. In addition, the majority of the residents are individuals that spend the majority of their time at home (Scotthanson and Scotthanson, 2004). There is one specific type of cohousing designed for elderly, known as senior cohousing. This type of cohousing has become popular due to some factors: firstly, according to Grundy (1998), the proportion of the population of the elderly people has increased because of the decrease in the rate of fertility and mortality (cited in Tinker, 2002, p 729). Secondly , “loneliness among the old is now endemic, giving rise to increasing public concern in recent years, making huge demands on the health and care service, and suggesting a pressing need for remedial action” (Brenton, 2017). Finally, Brenton (2008) proposed that at this stage of life, the need for a supportive community is more than any other. As a result, for senior citizens who spend most of their time at home, cohousing could be a valuable alternative to make the quality of their lives better.

Abraham, Delagrange, and Ragland (2006, p 3) argued that elderly people are not interested in nursing homes, retirement homes and etc. any more “instead, people are drawn to the idea of an old-fashioned, egalitarian neighborhood where neighbors help one another through the minor challenges of everyday life and support one another through the major ones”. Cohousing is a chance for seniors to look out for their emotional health after their children have moved away and spouses are infirmed (Durrett, 2009) and also experience the sense of community, belonging and neighborliness which are the main elements of the cohousing communities.

1.2. Theory and definition of sense of community

As mentioned before in this essay, the term community could be used in different ways but in this study both the notion of territorial and geographical community (neighborhood) and the relational communities (the quality of the relationship between members) have been considered. McMillan and Chavis (1986, p 9) proposed four elements for the creation of a sense of community: “membership, influence, reinforcement and shared emotional connection”.

1.2.1. Membership

Beckman and Secord (1959) mentioned in their study that membership is a feeling of belonging and being a part of the group (cited in McMillan and Chavis, 1986, p9). According to McMillen and Chavis (1986), membership consists of five attributes; the first attribute is having boundaries, meaning that there are people who are in and who are out of the group. These boundaries help people feel safe and protect their personal space. They also suggested having boundaries could result in the second attribute which is emotional safety. In addition, boundaries establish a feeling of security that members know who they can trust. The third attribute is a sense of belonging and identification which is defined as being a part of the group, having a place there and having a feeling of acceptance by the group. The fourth attribute of membership is personal investment which is explained by McMillan (1976, p 10) in the journal article of “Sense of Community: A Definition and Theory” as an effort for membership which “provides the feeling of having a place in the group”. The last attribute is common symbol system which has an important role for maintaining the sense of community (McMillen and Chavis, 1986). White (1949) characterized a symbol as “a thing the value or meaning of which is bestowed upon it by those who use it” which could be the name, logo or architectural style for a neighborhood (Cited in McMillan and Chavis, 1986, p 10). These five criteria should work together to create a sense of who belongs to the community and who does not.

1.2.2. Influence

Influence is another factor which could result in a sense of community. McMillan and Chavis (1986) summarized the concept of influence into four sections. First, the more members feel that they are influential for the group, the more they feel attached to that community. Second, members can influence the community as a result of how the community affects them or vice versa. As this relationship becomes stronger, it can result in the development of a tighter community. Third, the influence of the community on its members and cohesiveness have a vital positive relationship which could result in conform. “Both conformity and community influence on its members indicate the strength of the bond” (McMillan and Chavis, 1986, p 12) and last, this conformity plays an important role in the closeness of members and it is also an indicator of cohesiveness (McMillan and Chavis, 1986).

1.2.3. Reinforcement (integration and fulfillment of needs)

According to McMillan and Chavis (1986, p12), “reinforcement as a motivator of behavior is a cornerstone in behavioral research, and it is obvious that for any group to maintain a positive sense of togetherness, the individual-group association must be rewarding for its members”. Status of being a member, competence, and shared values are some of the criteria which could result in a closeness of the members of a group. In addition, by meeting everyone’s needs within the community, reinforcement can be made in order to strengthen the structure of the community (McMillan and Chavis, 1986).

1.2.4. A shared emotional connection

The interaction of members of the group in shared events makes the community stronger. However, interaction is not enough. The quality of the interaction also plays an important role in a community. If the experience of the interaction is positive, it could result in the greater bond. As an example, in most of the cohousing communities, there are so many events, planned by members of the community. These kinds of events which could be celebrations, meetings or traveling affect the relationship between the members who participated in the planning. According to McMillan and Chavis (1986, p 14), “the more important the shared event is to those involved, the greater the community bond”.

1.3. Theory and definition of sense of home

1.3.1. Use of the term home

The broad use of the term ‘home’ is sometimes equated with the term ‘house’. However, the terms ‘house’ and ‘home’ are diverse in the meaning, one has a physical aspect while the other is considered emotional. According to Melinda M. Swenson, PhD, RNCS, FNP (1998, p 391), “the house is a symbol of self, a symbol of aspirations, and a symbol of status” while “homes may be the outward manifestation of an inner reality, reflecting both her identity and her relationship to the larger community”. Home is not just a physical environment, it is the identity of individuals and it is the sense of self, especially for older people as they spend more time in their homes and as a result, the home plays an important role in the quality of their lives (Melinda M. Swenson, PhD, RNCS, FNP, 1998; Tanner, Tilse and Jonge, 2008). Melinda M. Swenson, PhD, RNCS, FNP (1998) believed that the house is necessary as a safe place for protection while a home is essential for human happiness.

1.3.2. Home is more than a physical environment

Tognali (1987), suggested five criteria which are the distinctions between a house and a home. These criteria are “centrality, continuity, privacy, self-expression and personal identity, and social relationships” (cited in Smith, 1994, p 31). Altman (1975) described centrality with the degree of power of individuals which means that the person could control what is happening around him/her in the place of home (cited in Smith, 1994, p 32). Home is a place for individuals to have exclusive control over it and it is also a primary territory (Smith, 1994). Moving to the next criterion which describes a home as a continuity, means that home is a permanent place to return to where you have a sense of belonging. Fried (1963) also mentioned that people with a low income who need to relocate their home have a loss of continuity and stability (cited in Smith, 1994, p 32). One of the most important characteristics of a home is privacy. According to Altman (1975), privacy is coming from the control that individuals have over the space and social interactions (cited in Smith, 1994, p 32). Smith (1994) also added that privacy allows individuals to feel that they are at ease and relaxed. The fourth characteristic of a home is self-expression and personal identity. Self-expression and personal identity is connected to individual’s development of themselves (Smith, 1994). They decorate their home in a way they think of themselves and the way they want others to think of them by putting their identity into their property, changing their house into their home. The last distinctive of a house and a home is the social relationship that takes place within it. Hayward (1977) proposed that home is a place for people to have social relationships with others (cited in Smith, 1994, p 33). People (neighbors, friends, and relatives) might come to their home in special social events under the control of the owner of the house. In short, according to Smith (1994), the positive social relationship, enough privacy and freedom, a sense of continuity and opportunities for self-expression could contribute a sense of home to the house (cited in Annison, 2000, p 258).

Part II

2. Case study

Figure 1: the New Ground Cohousing

2.1. The New Ground Cohousing

The New Ground Cohousing is the first senior cohousing community built in the United Kingdom. This project is located in the north of London (High Barnet) and it was completed at the end of 2016 (Brenton, 2017). Maria Brenton, who is the project consultant at Older Women’s Cohousing (OWCH), mentioned that the New Ground Cohousing includes 25 flats for 26 senior women aged from early 50’s to late 80’s. The idea of living in such a community came from 6 senior women who already knew each other in 1998 (OWCH, 2016). Due to the lack of support from housing association developers, it took 13 years for the OWCH to make this idea to the reality (Brenton, 2017). After finding a site in High Barnet, the OWCH participated in design with Pollard Thomas Edward architects (PTEA) (OWCH, 2016). According to Brenton (2017), the OWCH group asked for personal space, storage, shared facilities with plenty of light. The project had its own distinctive character because it was sitting between neighbored buildings with different architecture (Georgian, Victorian and more modern buildings) (Pollard Thomas Edwards, 2016).

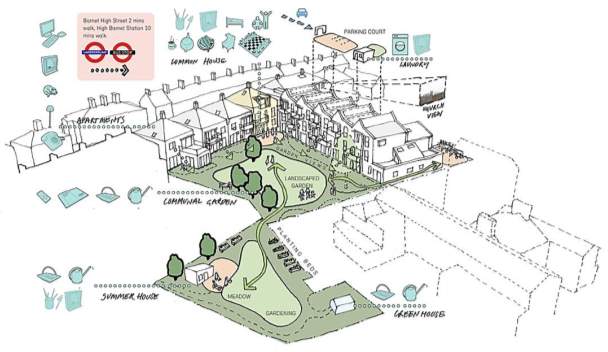

The New Ground Cohousing has easy access to many facilities such as High Barnet Underground Station and Barnet Hospital. The design of the New Ground is a T-Shape layout in which all the flats are facing a big shared garden in the center. This garden is the focal point of the designed which is connected to the “secret culture garden and craft” in the corner of the site (Pollard Thomas Edwards, 2016).

Figure 2: Ground Floor

Figure 3: First Floor

Figure 3: First Floor

Figure 4: Second Floor

Figure 4: Second Floor

Residents also have shared facilities such as a communal house with a kitchen and dining room. The large window of the communal house kitchen is facing the street, as a means for people from the outside of the building could feel the warm atmosphere of this site. In short, Brenton (2017) believed that the main purpose of the design of this project was for enhancing a sense of neighborliness for the residents whilst they age comfortably. The following essay will attempt to analyze how this project approached this purpose.

As mentioned earlier in this essay, visiting the site and interviewing with the residents of the New Ground Cohousing was not possible. However, in order to do the analysis, the videos published by the OWCH were used. The aim of these videos seems to show the success of the New Ground Cohousing Community. All the interviews and comments were positive and the OWCH tries to introduce the cohousing community and the way it works, to people who are not familiar with it. Although the videos give a lot of information about how the community works, the resident’s opinion might be changed over time, as they have only lived in the New Ground Cohousing for about a year.

2.2. Sense of community

The New Ground Cohousing consists of 26 senior women who decided to live in a community. Currently, the participant have been members from one year to 18 years (Brenton, 2017). According to OWCH (2017), all of the residents are either widower, single or their children have moved away. This community was shaped by 6 older women who already knew each other and it developed to 26 members after years. There were some boundaries for the new members who applied to join the community, they had to be adult women aged between 51 and 88 (Brenton, 2017). Brenton (2017) added that the volunteers should first participate in some meetings and social events, which as a result the existing members formally decided which of the volunteers can become a new member in respect to the following OWCH values:

The fact that this community consists of members who are women of similar age, it makes it easier for them to communicate and interact with each other. They are the same gender, they are all elderly and they felt isolated in their lives that they decided to live in a community, as understood from the video published by OWCH. Having some factors in common could result in the closeness of the community. When members feel close together, they can trust each other and they feel safe. According to Hed (one of the residents), when you get old, you feel less safe. In addition, Janet (one of the residents) mentioned that she used to live in a place where she did not know any of her neighbors because they kept changing. It can be understood that one of the advantages of living in the New Ground Cohousing is knowing your neighbors which as a result provides emotional safety. A sense of belonging also plays an important role in the community (McMillan and Chavis, 1986). A sense of belonging comes from the feeling that you are a part of the group and you have a place there. In the New Ground Cohousing, all members know each other and they care for each other. The feeling of acceptance by a group, who care for each other and help each other to improve the quality of their lives could result in a sense of belonging. Members feel that they belong to the community which they tried so hard to make and now when they see that all of their efforts resulted in the New Ground Cohousing Community they feel even closer.

In order for members to be attached to the community, they need to feel they have some influence on what the community does (McMillan and Chavis, 1986). The New Ground cohousing community has meetings once in a while which allows residents to talk about their responsibilities. Members of the cohousing divide into groups, with each group having a different responsibility such as finance, gardening, and housekeeping. Making decisions and sharing the responsibilities could give the members the feeling that they are indirectly controlling and influencing the community. In addition, this influence existed from the beginning, when all the members were involved in the project from designing to financing and shared a common purpose. Now, when they see the result, they know that without each of the member’s efforts, this project might not have been completed.

Another factor which is important in sense of community is integration and fulfillment of the members need (McMillan and Chavis, 1986). The New Ground cohousing community has similar needs, priorities, and aims, especially as they are all senior women. According to Brenton (2017, p 9), “for OWCH, agreeing a common understanding of cohousing and identifying the group’s core values was an early task”. One of the core values of the community is to care and support each other. According to one of the residents, she could get some help from one of the members to look after her cat when she is not home (OWCH, 2017). In addition, one major need this community has is socializing. Having people around who you can communicate with and the fact that they care for you could show that “in joining together they might be better able to satisfy these needs” (McMillan and Chavis, 1986, p 13).

The interaction and communication between the members will result in emotional connection if members have a positive experience from it (McMillan and Chavis, 1986). According to Brenton (2017), there are many social events and fun in the New Ground Cohousing Community. They have a weekly communal meal as well as doing many activities together such as meditation, yoga, and sketching (OWCH, 2017). One of the residents, Janet, mentioned that her most enjoyable moment in the cohousing is the common meal (OWCH, 2017). These activities provide the opportunity for the residents to interact with each other and as a result could strengthen the bond of the community.

It can be seen that there are many factors which could create a sense of community in the New Ground Cohousing. From the beginning, in 1998, a sense of community was built up and as the community live for longer together, their sense of community becomes stronger.

2.3. Sense of home

The residents were interviewed in the video provided by OWCH (2017), the reason they chose to live in cohousing was to improve their quality of life. Tanner, Tilse, and Jonge (2008) also mentioned that housing has an essential role in people’s health, well-being, and independence, particularly for elder people. This essay will analyze how the New Ground Cohousing generates a sense of home based on the theories mentioned in the literature review.

2.3.1. Centrality

The New Ground Cohousing Community was involved in the project from choosing the site and design till the project’s completion. This involvement and personal agency shows that members had control over the project from the initial stages. They asked the architect for lighting, storage, personal space, meaning they were the center of the design. In addition, they were also provided with private flats which are their own territory and have exclusive control over the environment. According to Brenton, the New Ground Cohousing is different from nursing or retirement homes, as here the residents are in charge in this community (OWCH, 2017) and that is what centrality is about.

2.3.2. Continuity

Vivien, one of the resident of the New Ground Cohousing noted she felt younger in this community as she expected she will live longer in there (OWCH, 2017). In addition, Janet, another resident, explained that from the time she moved into the New Ground Cohousing, the quality of her life got better and she wanted to tell everyone about cohousing (OWCH, 2017). It can be seen that the residents are hopeful for their future and they believe that this is the way they should live in this age. Thinking about having a place which is stable and permanent for them and they belong to that place is the continuity character of the home.

2.3.3. Privacy

Privacy plays an important role in the New Ground Cohousing, as the residents need to have the time to be at ease and relaxed outside of the community. Hedi (resident) explained that in the New Ground Cohousing “if I’m feeling like being on my own, I can be on my own and I can spends days without actually doing more than saying hi to people as I meet them going in and out” (OWCH,2017). The residents of the New Ground have their private homes with private balconies. They can spend time in their homes if they do not want to be in the communal house with other residents.

2.3.4. Self- expression and personal identity

Although the New Ground Cohousing residents need to make decisions in a group for the community, their own flats are the place for their self-expression and personal identity. The way they decorate their house could be a symbol of their personality. Some of the residents put pictures of their family in their house which could be a memory for them. Every time they look at the pictures it reminds them of a special event, the person which is known just by the owner of the house. All around the home is familiar, known and meaningful for them.

Figure 5: Apartments are generous spaces filled with light that have already acquired the feel of their occupants.

Figure 6: Inside, apartments feel personal sand sheltered.

2.3.5. Social relationship

One of the characteristics of a home is that it is a setting for social relationship enhancement (Smith, 1994). The main purpose of the New Ground Cohousing is the interaction and communication of the residents. All the members despite their private homes have the second home which is within the community. According to Brenton, the community consists of 26 senior women who know each other, look out for each other and share the core values (OWCH, 2017). They have become a large family of a large home called the New Ground Cohousing.

In short, the New Ground Cohousing generates a sense of home for the residents as the members feel privacy while they have social relations, centrality, continuity and their private homes are the symbols of their self-expression and personal identity.

2.4. A blend of privacy and communal life

As this essay has analyzed some data about the sense of community and sense of home in the New Ground Cohousing, the question which will be raised is how these work together in cohousing? According to Douglas (2015, p 192), “the most important thing about a co-housing scheme is that it is an intentional community, composed of individuals who have come together because they want to share the benefits of good neighborliness and some communality, but are also intent on training their independence and meaning their own lives”. Therefore, the OWCH was looking for a sense of community while they have their independence and privacy. This part of the essay is going to analyze the balance of privacy and communal life in the design of the New Ground Cohousing. However, it is first worth mentioning the process of the design.

2.4.1. Collaborative design process

According to (Devlin, Douglas and Reynolds, 2015) the design of the New Ground Cohousing was a collaborative design which means that the OWCH have participated in the design process. Patrick Devlin who is the architect of the project mentioned that some diagrams were suggested using symbols and markers by the OWCH after the site was picked, (Urban Design Group, 2013). Devlin, Douglas, and Reynolds (2015) noted that there were some similarities between the diagrams. Firstly, the co-house was in the center of the project. Secondly, all the apartments had a view of the garden. Finally, the entrances of the apartments were from the garden and not from the street. All of these features could be seen in the completed project which were the requests of the OWCH. There was also a diagram which suggested a social space in between the apartments and a larger social space in the center. Another diagram had private broken up spaces, located apart from each other, which was not acceptable for the project (Urban Design Group, 2013).

According to (Devlin, Douglas and Reynolds, 2015) the design of the New Ground Cohousing was a collaborative design which means that the OWCH have participated in the design process. Patrick Devlin who is the architect of the project mentioned that some diagrams were suggested using symbols and markers by the OWCH after the site was picked, (Urban Design Group, 2013). Devlin, Douglas, and Reynolds (2015) noted that there were some similarities between the diagrams. Firstly, the co-house was in the center of the project. Secondly, all the apartments had a view of the garden. Finally, the entrances of the apartments were from the garden and not from the street. All of these features could be seen in the completed project which were the requests of the OWCH. There was also a diagram which suggested a social space in between the apartments and a larger social space in the center. Another diagram had private broken up spaces, located apart from each other, which was not acceptable for the project (Urban Design Group, 2013).

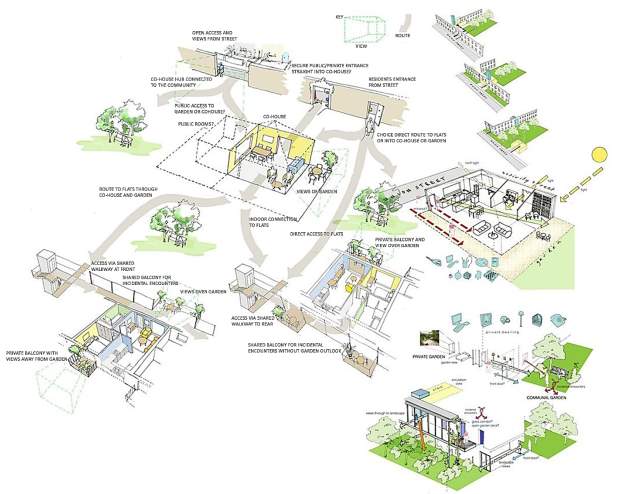

Figure 7 is one of the diagrams from Patrick Devlin about the public and private routes and boundaries with the common house. According to him, the upper side is the diagrams of how public face the community from the street. There were three entrance options for the site with one being an open access gate, another a secure public/private entrance straight into co-house and lastly a single resident entrance (Urban Design Group, 2013). The figure also shows the ranges of balconies of the flats, some of them are shared balconies and some are private. After various meetings with the OWCH, the building design was finalized.

Figure 7: Concept diagram mapping out public and private routes and boundaries with a co-house at center.

2.4.2. Analysis of the design

The final design is in 2-3 levels consisting of the landscape garden in the center and also a craft garden in the corner of the site. The main entrance is from Union Street which has access to the garden, co-house, and upper levels. As the OWCH requested, the entrances of the ground level flats are from the garden. In addition, the upper levels flats have private garden view balconies. The co-house is in the center and all the apartments are overlooked to the main garden.

Figure 8: The housing is tied together by the gardens.

2.4.3. Privacy and communal life in the New Ground Cohousing

The New Ground Cohousing consists of 25 private flats for members and 1 common house which is shared, two gardens, a parking court and a laundry to share. Although the common house is designed for social interactions, other communal spaces such as shared pathways, parking court and gardens also increase the potential for communication. The laundry has also the small garden which makes it possible for residents to enjoy the landscape and have a chat while they are waiting. Figure 9 shows the private, social, and public spaces of the New Ground Cohousing.

Figure 9: The private, social, and public spaces of the New Ground Cohousing

Figure 9: The private, social, and public spaces of the New Ground Cohousing

As shown in figure 9, this project is a private property with social and private areas. Social areas are places designed for social interactions whilst private areas are the places of independency and solitude. In this project, the majority of the site is occupied by social areas on the ground floor while the first and second floors are mostly private areas. Therefore, there is a balance between the private areas and social areas which resulted in the blend of privacy and communal life.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the aim of this essay was to analyze the case study of the New Ground Cohousing for a better understanding of how people gather to shape a community in order to live harmoniously. As cohousing is designed intentionally for people to enhance their social relationships and communication, it is important to consider the factors which could create a sense of community. The participation of the community members in the design, respecting the core values of the community, and having a shared emotional connection are some of the criteria which resulted in the sense of community and closeness of members in this project. Whilst the residents have a desire for being in a community in a cohousing scheme, they also require a private space as their home for dwelling. Thus, the members of the New Ground cohousing are given private flats where they can have exclusive control over the space and express their personal identity. Sense of home and sense of community have a crucial connection, as they are dependent on each other and existence of one could strength the other. Therefore, it seems that the cohousing scheme is a blend of privacy and communal life and the balance between privacy and sociability has a vital role for the residents in order to live harmoniously.

Taken together, this study offers some insight into the effects of housing in the quality of people’s lives. Due to loneliness and isolation becoming endemic all over the world, cohousing schemes could potentially be a sustainable model to address this problem particularly for elderly people who spend most of their time in their homes. As the New Ground Cohousing is the first of its kind in the UK, it could influence the development of future housing projects within this criteria.

References

Text books:

Durrett, C., 2009. The senior cohousing handbook: A community approach to independent living. New Society Publishers.

Lyon, L. and Driskell, R., 2011. The community in urban society. Waveland Press.

McCamant, K. and Durrett, C., 2011. Creating cohousing: Building sustainable communities. New Society Publishers.

Mental Health Foundation, (2016). Fundamental Facts About Mental Health 2016. Mental Health Foundation: London.

ScottHanson, C. and ScottHanson, K., (2005). The cohousing handbook. Gabriola Island, BC: New Society Publishers.

Tonnies, F. and Loomis, C.P., 1957. Community and society. Courier Corporation.

Journal articles:

Abraham, N., Delagrange, K. and Ragland, C., 2006. Elder cohousing: An idea whose time has come. Communities, 132, pp.60-69.

Annison, J.E., 2000. Towards a clearer understanding of the meaning of” home”. Journal of intellectual and developmental disability, 25(4), pp.251-262.

Brenton, M., 2008. The cohousing approach to ‘lifetime neighbourhoods’. The Housing Learning and Improvement Network http://www. housinglin. org. uk/Topics/browse/Housing/Commissioning.

Brenton, M., (2017). Community Building for Old Age: Breaking New Ground The UK’s first senior cohousing community, High Barnet. Housing Learning & Improvement Network. [online] Available at: https://www.housinglin.org.uk/Topics/type/Community-Building-for-Old-Age-Breaking-New-Ground-The-UKs-first-senior-cohousing-community-High-Barnet/ [Accessed 1 Jan. 2018].

Choi, J.S., 2004. Evaluation of community planning and life of senior cohousing projects in northern European countries. European planning studies, 12(8), pp.1189-1216.

Devlin, P., Douglas, R. and Reynolds, T., 2015. Collaborative design of Older Women’s CoHousing. Working with Older People, 19(4), pp.188-194.

Garciano, J.L., 2011. Affordable cohousing: Challenges and opportunities for supportive relational networks in mixed-income housing. Journal of Affordable Housing & Community Development Law, pp.169-192.

McMillan, D.W. and Chavis, D.M., 1986. Sense of community: A definition and theory. Journal of community psychology, 14(1), pp.6-23.

Smith, S.G., 1994. The essential qualities of a home. Journal of environmental psychology, 14(1), pp.31-46.

Melinda M. Swenson, PhD, RNCS, FNP, 1998. The meaning of home to five elderly women. Health Care for Women International, 19(5), pp.381-393.

Tanner, B., Tilse, C. and De Jonge, D., 2008. Restoring and sustaining home: The impact of home modifications on the meaning of home for older people. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 22(3), pp.195-215.

Tinker, A., 2002. The social implications of an ageing population.

Zaff, J. and Devlin, A.S., 1998. Sense of community in housing for the elderly. Journal of community psychology, 26(4), pp.381-398.

Websites:

OWCH. (2016). Home. [online] Available at: http://www.owch.org.uk/ [Accessed 6 Jan. 2018].

Pollard Thomas Edwards (2016). New Ground Cohousing | Pollard Thomas Edwards. [online] Pollardthomasedwards.co.uk. Available at: http://pollardthomasedwards.co.uk/project/owch/ [Accessed 6 Jan. 2018].

Videos:

OWCH (2017). Senior Cohousing – the way to do it. Vimeo,

Available at: https://vimeo.com/242947993 [Accessed 6 Jan. 2018].

Urban Design Group (2013), Patrick Devlin: Realising cohousing in practice, Urbannous Ltd.,

Available at: http://www.urbannous.org.uk/Patrick-Devlin-PTE-architects.htm

You have to be 100% sure of the quality of your product to give a money-back guarantee. This describes us perfectly. Make sure that this guarantee is totally transparent.

Read moreEach paper is composed from scratch, according to your instructions. It is then checked by our plagiarism-detection software. There is no gap where plagiarism could squeeze in.

Read moreThanks to our free revisions, there is no way for you to be unsatisfied. We will work on your paper until you are completely happy with the result.

Read moreYour email is safe, as we store it according to international data protection rules. Your bank details are secure, as we use only reliable payment systems.

Read moreBy sending us your money, you buy the service we provide. Check out our terms and conditions if you prefer business talks to be laid out in official language.

Read more