THE EFFECT OF MINIMUM WAGE ON YOUTH UNEMPLOYMENT; THE UK CASE

The effect of the UK minimum wage on employment always has been a key topic of research and debate within the field of economics. Whether it’s effect is positive or negative for employment, and more specifically youth unemployment, can have a significant consequence on the economy, which is the reason that both politicians and economists pay such interest to any changes to the level of the minimum wage. This paper aims to theoretically outline the methodology needed to find the effect that a change in the level of the minimum wage has on youth employment. It recommends the use of data from three different datasets – the Labour Force Survey, the British Households Panel Survey and the New Income Survey – and also provides checks for robustness of the results found. A difference-in-differences estimator is used to perform this analysis, and all methodology involved for this is included.

Table of Contents

Introduction & Summary of Literature Review

Difference-in-Differences Estimator

Appendix 2: Risk Assessment Form

Introduction & Summary of Literature Review

Part 1 of this dissertation aimed to outline the current literature surrounding the field of unemployment, and specifically, youth unemployment in the UK, with regards to the minimum wage. The minimum wage for young people has been increasing for the last 2 years in the UK, and as such, this is a very relevant topic. As was found within the literature review, much research has been undertaken on the effects of the minimum wage on youth employment prospects in other countries around the world, however, comparatively little has been done in the UK.

One such other country which has been investigated is Spain, where Teulings et al., 1996 found that the increase in the youth minimum wage in 1990 led to a decrease in youth employment levels in the country. Prior to the increase of the minimum wage, there were separate minimum wages for 16, 17 and 18 year olds – However, these separations were removed in 1990, leading to an 83% increase in minimum wage for 16-year-old workers and a 15% increase for 17-year-olds. These vast increases in minimum wage led to an overall decrease in youth employment levels, despite employment in the economy as a whole increased. Whist the author of this paper doesn’t specify a specific percentage decrease in youth employment levels for every percentage increase in minimum wage, he does back up his claim that employment levels were negatively affected in a latter paper (Jimeno et al., 1997).

Another country where specific research has been carried out on youth employment levels subject to the youth minimum wage is France. When most countries decide to increase the youth minimum wage, they normally do so in an incremental fashion, with year on year increases in order to not have too large an effect on employers and employees. However, France’s implementation was different as the youth minimum wage was increased by 10% overnight in 1981 following Francois Mitterand’s election as president. This acted as a good platform for Bazen and van Soest, 1994 to investigate the effect on young workers of such a dramatic increase in minimum wage. The authors of this paper found that following the increase, youth employment within the economy fell from 14.6% to 12.9%. They went on to explain that this may have been due to young workers earning a much closer wage to adult workers, and thus employees would have preferred to employ more experienced older workers than young inexperienced workers on a higher salary. Another paper by Margolis et al., 1997 also investigated the same rise in youth minimum wage, and came to the same conclusion as Bazen and van Soest. However, their paper adds an interesting caveat, which was that around the same time as the increase in youth minimum wage, several employment incentive programs for young workers were started. This meant that the increase in minimum wage was offset to a certain extent by programs such as the TUC and SIVP, for workers up to the age of 25. However, the fact that employment of young workers fell despite these programs being in place, shows that if these programs had not been present, youth employment levels could have fallen drastically further.

One issue with current literature which was brought to light in the literature review was contradicting results when researching the effects of changes in the minimum wage on youth unemployment within the same economy. Different research papers covering the aforementioned economies, Spain and France, aligned in their conclusions, despite sometimes differing on the level of the effect. However, this is not the case for all countries, as the example of the Netherlands shows. In the 1980s’, the youth minimum wage was reduced greatly due high youth unemployment. Following this change, Bazen and van Soest, 1994 attempted to analyse the effect that it had on the level of youth unemployment, and while not stating a specific percentage change, they came to the conclusion that it had a negative effect on employment levels. They also further specified that it had a negative effect on the employment of young male workers, while it had a positive effect on young female’s enrolment in education. Teulings et al., 1996 also analysed the effect of the change in the youth minimum wage of the 1980s’, however they came to a different conclusion than Bazen and van Soest. They concluded that dependent on the industry, the effect of the change in minimum wage was different in different industries. For instance, youth employment increased in the agricultural sector following the change, from 21% to 25%, while it remained constant in the unskilled industrial sector, at 14%. They also noted that youth employment levels decreased in the kitchen and household staff industry, from 26% to 24%. They did however conclude that overall, youth employment fell in the economy by 4% – the same conclusion that Bazen and Van Soet came to. Teulings et al., concluded that it would be unjust to say that the effect of the change in minimum wage was entirely negative, and thus this shows the difference in the two papers.

Another country where contrasting conclusions can be found about the effect of a change in minimum wage is New Zealand. In the case of New Zealand, there was no specific ‘youth’ minimum wage prior to 1994, as there was only a ‘young adult’ minimum wage for workers aged between 20-24. However, as both papers that will be mentioned used data form prior to 1994, the data being used was constant. Maloney, 1995 analysed the changes in the ‘young adult’ minimum wage and concluded that a 10% increase would result in a decrease of employment of ‘young adults’ of 3.5%. Maloney also added that a 10% increase in the adult minimum wage, would result in an increase of 6.9% of teenage employment. This is an interesting conclusion to add, as it shows that employers choose their low wage employees based on wage rather than experience level, which adult workers would have more of. Maloney’s paper was followed by Chapple, 1997, whose conclusion contradict that of Maloney. Chapple firstly criticised Maloney’s paper, by stating that some of the equations that he used were subject to auto-correlation, which thus could invalidate the results. He also criticised Maloney’s use of his time series equation, as it was not stable over the entire time period analysed. Following Chapple’s comments on Maloney’s paper, the author analysed the effect of the changes in the ‘young adult’ minimum wage on youth employment. It was concluded that changes in the ‘young adult’ minimum wage level have only ever led to minimal changes in employment of young people, which are not of statistical significance. Thus, it can be seen that these two research papers came to different conclusions as to the effect of changes in the ‘young adult’ minimum wage on youth employment.

One possible reason for the literature not always aligning in its results is that different types of data are used. This is show when Margolis et al., 1997 used longitudinal data when investigating the effect of the increase in the youth minimum wage on youth employment in France in the 1980s’. In contrast, Teulings et al., 1996 used regional variation in minimum wages to analyse the effect of the same increase in the youth minimum wage, in the same country (France), over the same time period as Margolis et al. As such, they both came to different conclusions, possibly due to the fact that they were using different data.

Whilst it has been shown that papers covering the effect of changes in the minimum wage on youth employment exist widely for countries other than the UK, papers regarding the UK economy are hard to come by. As such, as was stated in Part 1 of this dissertation, more research into the UK economy is required, specifically regarding youth employment and possibly, the youth minimum wage. While this paper will not specifically fill this gap, it will theoretically aim to provide the methodology for doing so, by answering the following research question: What is the methodology required for establishing whether it is possible to increase the minimum wage without increasing youth unemployment in the UK? This will be answered by defining the methodology required for performing a difference-in-differences estimator, outlining the data required to do so, and also providing several robustness checks for the results that would be produced by this model.

In order to estimate the effect of changes in the youth minimum wage on the employment levels of youths in an economy, longitudinal data must be used to compare the employment status of workers whose wages have increased as a result of the change in the minimum wage, against those whose wages haven’t changed. The natural method for performing this comparison is by using a difference-in-differences estimator. When analysing a change in the level of the minimum wage, it would be fair to make the assumption that workers whose wages changed due to the change in minimum wage would be more affected than workers whose wages have not changed – i.e. those at a higher wage level. However, it would not be a fair comparison to compare these two groups of employees due to their different wage levels, and as such, a difference-in-differences estimator is the right one to take. The difference in employment probability levels between these two groups of employees before and after the change in the minimum wage can be compared using this estimator.

The following model is used from a paper by Stewart, 2004 regarding the implementation of the UK minimum wage in 1999. In has been adapted slightly in this paper to suit the different situation – a change in the minimum wage, as opposed to its implementation. In this model, e0it is defined as the employment status of a given individual, i, in time period, t, before the change in the minimum wage, where it is set to 1 if the individual is employed and 0 if not employed. Following the change in minimum wage, e1it is used, with the same values for employment status – it must be mentioned that for any given individual, only one value is observed in a given time period. For the time period value, we will assume that the minimum wage change in question occurred at time t*, and that the minimum wage was at its original level before t*. Workers within the UK economy are also classified into groups, g. With these definitions, it can then be said that in a given time period, t, for a given group, g, we can measure the employment rate; The rate prior to the change in minimum wage can be measured when t < t*, Ee0it g, t, and the rate after the change can be measured when t > t*, Ee1it g, t. From this, we can estimate what the employment level would have been in a given group, g, had the minimum wage not changed, by using the following formula, Ee0it g, t, t t*. This therefore leads onto the following equation:

Ee0it g, t = g + t (1)

In this equation, the g component remains constant across different time periods, while the t remains fixed across different groups. Thus, we can assume that prior to a change in the level of the youth minimum wage, the difference between different groups, g, will be the same in each time period, t. This is a crucial assumption to make, as it is key to the difference-in-differences estimator.

Following on from this equation, we can use differencing to find the difference-in-differences estimator. For this, we assume that the change in the youth minimum wage has a constant effect on group 1:

Ee1it 1, t = Ee0it 1, t + θ

However, we assume that the change in the youth minimum wage has no effect on group 2:

Ee1it 2, t = Ee0it 2, t

Next, the factor of the two different time periods can be added into the equation. Prior to the change in minimum wage was t1, and following the change was t2. We can therefore difference across both time periods and both groups to find the difference-in-differences estimator:

{ Eeit 1, t2 – Eeit 2, t2 } – { Eeit 1, t1 – Eeit 2, t1 } = θ

Now that this simple estimator has been found by double differencing, the employment statuses of individuals can be written for all time periods and groups as follows using equation (1):

Eeit g, t = g + t + θDit + εit (2)

In this equation, the Dit component is equal to 1 if the individual is affected by the change in the minimum wage. The estimator that was found above, can also be found by performing a regression using data pooled from several different groups and different time periods. This value is then added to additive group and time dummy variables, as well as an extra value which is found by measuring the interaction between the first group’s dummy variable and a dummy variable for all time periods after the change in minimum wage.

In his paper from 2004, Stewart separates the individuals involved in his study into three set groups that represent divisions of the real wage distribution. The first group that he defines covers individuals with the lowest wages – wages which are below the new minimum wage before it changed, and thus will be directly affected by an increase in the minimum wage. The second group contains individuals whose wages are between the new minimum wage after it had changed and a point slightly higher than the new minimum wage. The third group encompasses all individuals in the rest of the wage distribution. This separation technique was also used by Abowd et al., 2010, and Neumark et al., 2000.

The simple difference-in-differences equation (2) can be further extended with the addition of an extra variable, xit. This variable will now mean that the estimator is “regression adjusted”, as the characteristics that are covered by the new variable act as control variables in equation (2). These control variables will remove any differences between the treatment group (g = 1) and the control group (g = 2) that were not removed by the additive group and time dummy variables previously mentioned. Equation (3) can be written as follows:

eit = xit’β + g + t + θDit + εit (3)

There are several key assumptions associated with this difference-in-differences estimator. The first of these has been mentioned above, and states that prior to the change in the minimum wage, the difference in employment rates between the treatment group and the control group must remain constant in each time period. In other words, the change in employment over time in each group must be the same prior to the change in the minimum wage. This assumption may be challenged though as even without the introduction of a minimum wage, the growth in employment levels may inevitably differ over time in different groups. The second key assumption to make is that the change in the minimum wage does not affect the employment probabilities of the control group. This is crucial as the control group must stay constant over the entire time period being analysed. However, this assumption may also be challenged by the issue of wage spillovers. This would occur when workers paid just above the minimum wage prior to its increase, may be paid more after the change in the minimum wage in order to keep a separation to the lower paid employees.

When using the model outlined above, it is best to use several different types of data, as each data source has its advantages and its disadvantages. In order for a dataset to be suitable for the model, it must fulfil several requirements. Firstly, the data in the data set must span a period before and after the given change in the youth minimum wage. In the case of Stewart’s paper for example, the data would have needed to span the introduction of the minimum wage in 1999. Secondly, the dataset must have a matched cross section of at least two time periods, as the model estimates the probability of employment at time t+1 as a function of wage at time t. Thirdly, the data source must give employment statuses of individuals for the second time period, t+1, as well as the individuals hourly wage in the first time period, t. This data will be used to see how a given individual was affected by the change in the minimum wage. Fourthly, information on other factors that influence the probability of being employed after the change in minimum wage must be given. This is in order to create appropriate control variables for the model. Finally, the data set must provide a relatively large sample of individuals, as this is required by a difference-in-differences estimator.

The three different types of data that would be suitable for this model in the UK, given all of these requirements, are the following: The Labour Force Survey (LFS), the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS) and the New Earnings Survey (NES). As mentioned, each of these different data sets has their advantages and their disadvantages. The LFS for instance has a better representation of lower paid workers than the NES, and provides a larger sample size than the BHPS. However, it has more limited panel dimensions than the BHPS and has potential measurement errors in the hourly pay rates when compared to the NES. In contrast, the BHPS has the advantage over the NES that its data covers the complete earnings distribution, and that it holds more information over individuals’ specific characteristics. Its main drawback however, is that it has a much smaller sample size than the LFS and the NES. The NES on the other hand has the advantages that its wage data is very accurate as most of it comes directly from payroll records, as well as the very large sample size of the data that it produces. It’s main weakness however is that an individual does not necessarily appear in the survey year on year. As the survey only covers people in employment, it could be inferred that when an individual does not appear in the survey a year after they did appear, they are out of employment. However, an individual will also not be present in the survey if they fall below the PAYE deduction threshold for weekly earnings. This will most likely affect part-time employees, or individuals who have changed from full-time to part-time work. As such, it can be seen that no data set is perfect, however, they all complement each other in different ways and are thus all suitable for a difference-in-differences estimator.

The difference-in-differences model that has been used in this paper requires there to be a clear distinction between the treatment group and the control groups. There are several factors that could potentially affect this distinction, and one of these is spill-overs. This would occur when those paid slightly above the rate of the new minimum wage (after the increase) may be given a pay rise in order to maintain their wage differential to those who are paid lower wages. Having said this, Stuttard and Jenkins, 2001 found that there has been very few signs of such spill-over effects in the UK since the implementation of the minimum wage in 1999. Dickens and Manning, 2001, also came to the same conclusion, and added that the case of the UK contrasts that of the US in this sense.

Defining the control group is also very important for the model. However, doing so may not be as straight forward as it may seem, as there is a compromise. It is ideal to have a narrow definition for the control group as this makes it simpler in practice to keep this group similar to the treatment group. However, by enlarging the definition of the control group and moving it higher up the wage distribution, the risk of wage spill-overs will be reduced. On top of this, as the group is larger, the issue of misclassification between the two groups as a result of measurement error is less. A larger group size would also result in a more accurate model result.

One more key requirement for the model is that there is a clear distinction between the time periods before and after the change in minimum wage. This may not occur if a part of the increase in wages had already been performed by employers before the date of the legal change in the minimum wage. This would, in essence, lead to a gradual increase in the minimum wage paid to workers, and the difference between the before and after phases would be partially undermined.

When carrying out the difference-in-differences estimator outlined above, the results will inevitably need to be checked for robustness. By using different data sources, different tests and modifications will need to be carried out on the different results. Looking at the LFS results, there are several factors which could have affected the results. Firstly, in the LFS data, an average hourly earnings measure is used that is averaged across all hours worked. This means that overtime hours are paid at the same rate as basic hours of work. In order to verify whether overtime hours would have had an effect on the overall results, a percentage premium for overtime hours could be added into the model.

Another potential flaw with the LFS survey data surrounds the definition of employed and non-employed. For instance, traditionally, workers employed in government employment and training programmes, and unpaid family workers count as employed in the basic definition of employment. However, if they are counted as non-employed the results may change, and thus this should be checked for robustness. Conversely, individuals who do not wish to work and would not accept a job given to them (economically inactive) are counted as non-employed, along with the unemployed. As such, the results of the model may be affected when this group of economically inactive individuals is removed from the data sample, and for this reason, another check for robustness should be carried out by modifying the definition of “non-employed” individuals.

Regarding the BHPS, the same checks for robustness should be carried as for the LFS, as the data suffers from the same drawbacks as mentioned above. However, when investigating the NES results, certain robustness checks would not be needed due to the different data in the data set. For instance, no modification would need to be made to the data regarding overtime pay, as there is are separate measures for basic and overtime pay in the NES data.

This paper aims to outline the methodology needed to find the effect that a change in the level of the minimum wage has on youth employment. It recommends the use of data from three different datasets – the Labour Force Survey, the British Households Panel Survey and the New Income Survey – and also provides checks for robustness of the results found. A difference-in-differences estimator is used to perform this analysis, and all methodology involved for this is included.

While this paper is merely theoretical, it provides much scope for future research. This is because a gap in the literature has been found, where no empirical analysis on the current youth minimum wage has been performed since the implementation of the minimum wage in the UK in 1999. The effect of the youth minimum wage on employment always has, and always will, be a key topic of research and debate within the field of economics. Whether it’s effect is positive or negative for employment, and more specifically youth unemployment, can have a significant consequence on the economy, and for this reason, it is an area of research that will always be relevant.

Word Count: 3999

Abowd, J., Kramarz, F., Margolis, D. and Philippon, T. (2010) The Tail of Two Countries: Minimum Wages and Employment in France and the United States. IZA Discussion Papers, 203. Available from: http://ftp.iza.org/dp203.pdf [Accessed 12 April 2017].

Bazen, S. and van Soest, A. (1994) Youth minimum wage rates: The Dutch experience. International Journal of Manpower, 15 (2/3), 100-117.

Bazen, S. and van Soest, A. (1994) Youth minimum wage rates: The Dutch experience. International Journal of Manpower, 15 (2/3), 100-117.

Brown, C., Gilroy, C. and Kohen, A. (1982) The Effect of the Minimum Wage on Employment and Unemployment: A Survey.

Brown, C., Gilroy, C. and Kohen, A. (1983) Time-Series Evidence of the Effect of the Minimum Wage on Youth Employment and Unemployment. The Journal of Human Resources, 18 (1), 3.

Chapple, S. (1997) Do minimum wages have an adverse impact on employment? Evidence from New Zealand. Available from: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.600.103&rep=rep1&type=pdf [Accessed 4 December 2016].

Dickens, R. and Manning, A. (2001) The National Minimum Wage and Wage Inequality. Centre for Economic Performance, LSE.

Dickens, R., Machin, S. and Manning, A. (1999) The Effects of Minimum Wages on Employment: Theory and Evidence from Britain. Journal of Labor Economics, 17 (1), 1-22.

Hashimoto, M. (1982) Minimum wage effects on training on the job. The American Economic Review, 72 (5), 1070-1087. Available from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/1812023.pdf [Accessed 18 November 2016].

Jimeno, J., Felgueroso, F. and Dolado, J. (1997) The effects of minimum bargained wages on earnings: Evidence from Spain. European Economic Review, 41 (s 3–5), 713–721. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0014292197000032 [Accessed 21 November 2016].

Krueger, A. and Card, D. (1994) Minimum wages and employment: A case study of the fast-food industry in new jersey and Pennsylvania. Available from: http://davidcard.berkeley.edu/papers/njmin-aer.pdf [Accessed 15 November 2016].

Machin, S. and Manning, A. (1994) The Effects of Minimum Wages on Wage Dispersion and Employment: Evidence from the U.K. Wages Councils. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 47 (2).

Maloney, T. (1995) Does the adult minimum wage affect employment and unemployment in New Zealand?. New Zealand Economic Papers, 29 (1), 1-19.

Margolis, D., Lemieux, T., Kramarz, F. and Abowd, J. (1997) Minimum wages and youth employment in France and the United States. Available from: http://www.nber.org/papers/w6111 [Accessed 10 December 2016].

Narendranathan, W. and Elias, P. (2009) INFLUENCES OF PAST HISTORY ON THE INCIDENCE OF YOUTH UNEMPLOYMENT: EMPIRICAL FINDINGS FOR THE UK†. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 55 (2), 161-185.

Neumark, D., Schweitzer, M. and Wascher, W. (2000) The Effects of Minimum Wages Throughout the Wage Distribution.

Pratomo, D. (2016) How does the minimum wage affect employment statuses of youths? Evidence of Indonesia. Journal of Economic Studies, 43 (2), 259-274.

Skourias, N. and Bazen, S. (1997) Is there a negative effect of minimum wages on youth employment in France?. European Economic Review, 41 (s 3–5), 723–732. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0014292197000044 [Accessed 9 December 2016].

Stewart, M. (2004) The Impact of the Introduction of the U.K. Minimum Wage on the Employment Probabilities of Low-Wage Workers. Journal of the European Economic Association, 2 (1), 67-97. Available from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/40004869.pdf [Accessed 10 April 2017].

Stuttard, N. and Jenkins, J. (2001) Measuring low pay using the New Earnings Survey and the Labour Force Survey. Labour Market Trends, 55-66.

Teulings, C., Margolis, D., Manning, A., Machin, S., Kramarz, F. and Dolado, J. (1996) The economic impact of minimum wages in Europe. Original Articles, 11 (23), 317-372. Available from: http://economicpolicy.oxfordjournals.org/content/11/23/317.abstract [Accessed 21 November 2016].

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON

SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES

ECONOMICS

THE EFFECT OF MINIMUM WAGE ON YOUTH UNEMPLOYMENT; THE UK CASE

–PART 1 –

Barrett Fransen

Presented for B.Sc. (Social Sciences) Economics and Management Sciences

April 2017

I declare that this dissertation is my own work, and that where material is obtained from published or unpublished work, this has been fully acknowledged in the references.

Signed: …………………………………………………………

Table of Contents

Possible causes for Inconsistent Results

The Specific Case of Youth Unemployment

The Specific Case of Developed versus Undeveloped Countries

Introduction

The effect of the UK minimum wage on employment always has been a key topic of research and debate within the field of economics. Whether it’s effect is positive or negative for employment, and more specifically youth unemployment, can have significant consequences on the economy, which is the reason that both politicians and economists pay such interest to any changes to the level of the minimum wage. According to the theory of perfect competition, employers should reduce employment following a rise in the minimum wage (Stigler, 1946). The level of the decrease in employment will depend on the size of the increase in the minimum wage, as well as the slope of the labour supply. The labour supply curve is downward sloping, due to decreasing returns in the production function, however, the gradient will depend on the economy. Under certain circumstances and cases of monopsony, there is even some evidence to prove that a rise in the level of the minimum wage can lead to a rise in the level of employment (Dickens et al., 1994). An example of these conditions may be a job requiring a set of very specific skills, such as a diving compressor repair technician. In this case, the firm will not be facing an infinitely elastic supply curve, and for this reason, employment can rise when the minimum wage rises. As such, the minimum wage is an extremely vital tool within an economy which can prove to have serious effects on the level of employment if the circumstances are not properly analysed beforehand.

The minimum wage can, as explained, affect employment levels. However, this is a very broad statement, as a change in the level of the minimum wage will affect different areas of the labour workforce differently. One demographic that will be particularly affected is that of young workers. While the effect of the minimum wage on adult unemployment levels is a vastly covered field within economic literature, there is, surprisingly, very little literature on its effect specifically on youth unemployment in the UK. Therefore, this paper aims to fill this gap in research, with the following research question: Is it possible to increase the minimum wage in the UK, without increasing youth unemployment? In order to do this, several aspects of the UK labour market will be analysed in detail, including, the history of the minimum wage, as well as historical unemployment levels. This will be followed by a ‘difference-in-difference’ (DiD) comparison of the UK labour force with another similar, European economy.

According to the United Nations, ‘youth’ is defined as anyone aged between 15 and 24 years old (United Nations, 2016). In the real world, ‘youth’ is defined slightly differently, and varies from country to country. In the UK for instance, it is considered to be between the ages of 16, the age when school no longer becomes compulsory, and 24. Young workers make up 11.8% of the entire UK labour workforce, while the current youth unemployment level is 13.1%, as of September 2016 (ONS, 2016b). ‘Unemployment’ is defined by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) as being when someone has not worked in a given reference period (normally the past week or month), is currently available for work, and is seeking work (Cornu and Vittorelli, 1996).

There are several reasons why young workers are often more affected than older workers when the minimum wage is increased. The first of these is that they are frequently the employees with the lowest wages in a company, often near the minimum wage level. Thus, if the minimum wage level is increased, they will be the first to bear the brunt of a company reducing its employment level. Another reason is somewhat more interesting – young workers tend to have low levels of experience, and as such, are willing to accept lower wages in return for gaining experience (Gorry, 2013) . In this way, these young employees benefit in two ways from employment: firstly, in the form of their wage, and secondly, by increasing their experience of the workplace. This means that a higher minimum wage level will possibly not only prevent them from gaining a low-wage job that matches their experience level, but also stop them from gaining valuable skills and experience (Hashimoto, 1982) . This could even potentially carry over to adult unemployment, as the young people in question were unable to gain as much experience as they would have, had they been employed and gained experience when they were younger.

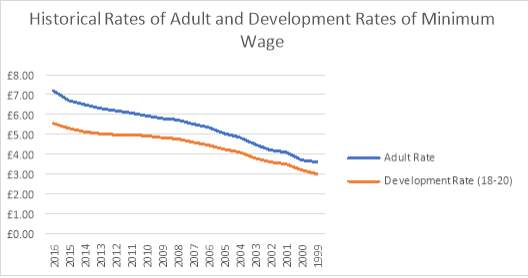

As previously mentioned, the national minimum wage was first implemented in the UK in April of 1999. Prior to this, there was a system in place known as the Wages Council system, which was established in 1909. It acted as a bargaining tool for its peak number of members of 3.5 million in 1953, most of whom were low-paid workers. The system was abolished in 1993, and from then until 1999, there was no minimum wage system in place (Metcalf, 1999) . Following a change of government in 1997, a national minimum wage was implemented on the 1st of April 1999 of £3.60 for adults aged 21 or older. Even from this early stage, it was recognised that young people would suffer more than more experienced adults as a result of this minimum wage. As such, a ‘development rate’ wage was put in place at the same time, at a level of £3.20 for those aged between 18-20. Both rates have steadily been increasing since they were implemented, as can be seen on the graph below (ONS, 2016a). In 2016, a new ‘young adults’ bracket was implemented for those between the ages of 21 to 24, aimed at bridging the expanding gap between the adult rate and the development rate of the minimum wage.

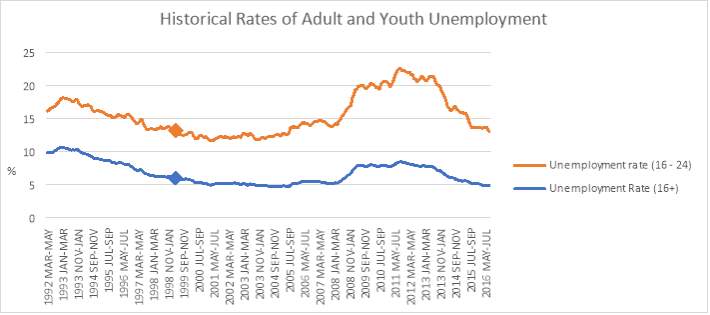

Youth unemployment over time, has matched the general trend of adult unemployment, while being proportionately higher. Following the implementation of the minimum wage on the 1st of April 1999, there was no significant drop in unemployment levels, which can be seen on the graph below (ONS, 2016c). The enlarged marker on both lines represents the 1st of April 1999. Despite there being no significant sudden effect at the time of implementation, a year later, youth unemployment had fallen by 0.4%, while adult unemployment had fallen by 0.5%. These represent marginal falls which could be attributed to the implementation of the minimum wage, however, the trend of unemployment at the time of implementation was downward.

The effect of minimum wages on employment and unemployment statistics is a widely-covered topic within research papers. Its effects have been investigated in great detail over a large period of time, as well as over a number of specific industries, and in different countries. The employment effects of the minimum wage in the UK is interesting as there are some contradicting results in research papers, as is also the case for the Netherlands and New Zealand which will be looked into later. As has been previously mentioned, according to the theory of perfect competition, when the minimum wage is increased, employment levels should fall. This more “textbook” theory has been supported in the specific UK case by Minford and Ashton (1996c), as mentioned by Machin and Manning (1997e) in their paper on minimum wage effects in Europe. However, this report is contradicted in two other prominent papers. In the first of these, Machin and Manning (1994b) claim that a decrease in the minimum wage can lead to an increase in employment – Though, it must be mentioned that this paper analyses the old Wages Council system. In fact, it also goes on to add that minimum wage has either no effect or a slightly positive one on employment statistics, rather than a negative one. A later paper also by Machin and Manning (1996b), found that through all of the evidence analysed, the employment effects of a change in the minimum wage were minimal. As with the previous paper, it also goes on to add that assuming the minimum wage is set at an “appropriate” level, many workers in the UK stood to gain from the implementation of the minimum wage (which was not in place at the time of writing), most notably, women.

As shown in the example of the UK, different papers covering the same country’s labour force, can sometimes come to different conclusions. Research papers covering other countries have also led to differing results. An example is the Netherlands, where the youth minimum wage was reduced greatly in the early 1980s’ due to high youth unemployment. In particular, the comparatively high youth unemployment at the time led to the minimum wage for young workers being reduced by a proportionately higher amount than the adult minimum wage. Following this decrease, two particular research papers analysed the effect that this change had on youth unemployment and came to vastly different conclusions. Van Soet (1994c) concludes that though micro-econometric analysis and estimated elasticities, minimum wages do negatively affect employment probabilities of young workers. The paper also states, that there is a negative effect on unemployment for males, while females experience a positive effect on enrolment in education. Dolado, et al. (1996a), on the other hand, came a different conclusion. The paper found that following the youth minimum wage decreases in 1981 and 1983, the youth share of total employment in the economy fell by 4%. Despite this overall decrease, the youth employment share of different industries was affected differently over the time period analysed (1979 to 1985) – youth employment decreased for kitchen and household staff (26% to 24%), youth employment increased for agricultural labour (21% to 25%), while youth employment remained constant for unskilled industrial labour at 14%. However, taking all of these effects into account, the paper concludes that in the Netherlands, the reduction of the youth minimum wage did cause an increase in youth employment in certain industries that are likely to be affected. Nonetheless, these changes are only marginally statistically significant and thus the effects of the minimum wage on youth employment are negligible at best. Therefore, these two papers are a classic example of inconsistent results, when observing the same country, after the same change in minimum wage.

Another example of these varying results can be found in papers observing New Zealand. It must be noted that this specific country didn’t have a separate minimum wage for teenagers before 1994. However, both of these papers analyse the effect of changes before this period, so the data being used is constant. It did however have a separate minimum wage for young adults. Maloney (1995), as with Van Soet’s previously mentioned paper, quite boldly concludes that an increase in the minimum wage of 10% led to a decrease of employment of young adults (aged 20-24) of 3.5%. Another interesting conclusion that the paper stated was that a 10% increase in the adult minimum wage led to a 6.9% increase in teenage employment. This is an interesting finding which is somewhat contradictory to other papers of the same subject. A different paper by Chapple (1997c), as with the example from the Netherlands, contradicts Maloney’s paper – However in this case, it does so in two ways. Firstly, it looks at Maloney’s paper in surprising detail, and criticises some of the methodology and data used. For instance, it states that the time series equation used by Maloney was not stable over the entire time period, thus jeopardising some of the paper’s findings. It also states that some of the equations used by Maloney are susceptible to auto-correlation, which again, threatens the legitimacy of the results of the paper. Chapple then goes on to analyse the employment effects of young people of changes in the minimum wage, and finds that increases in the minimum wage have only ever led to minimal changes on employment, which are not statistically significant. Therefore, as with the case of Netherlands, this is an example of two papers’ results contradicting each other.

Contradictory to the cases of the Netherlands and New Zealand, papers researching certain countries have found consistent results of the effects of changes in minimum wages. One such example is that of Spain, where, as of 1990, there were two wage brackets: one for workers aged between 16 and 17, and one for workers aged 18 and over. Before 1990, there was an extra age bracket for 16-year-old workers – however this was removed in 1990, which caused the minimum wage for 16-year-old workers to increase by 83%, and for 17-year-old workers by 15%. These two papers analyse the effects of these changes. Dolado, et al. (1996a) states that, while not specifying any exact figures, the increase in the youth minimum wage in the 1990s’, led to a decrease in employment of young workers. A large caveat that the paper also mentions is that over the same time period, employment in the industry as a whole increased, meaning that only young workers of the economy were negatively affected by the change. Dolado, et al. (1997d) later also backed up the previous findings, by indirectly stating that an increase in the youth minimum wage lead to a decrease of employment of young workers.

Another case of papers finding coherent results in the same country is that of Canada. The minimum wage case is slightly different in this country compared to some others previously mentioned, in the sense that the minimum wage is not federally controlled. Instead, it is provincially set, which makes its analysis more interesting as inter-province comparisons can be made. Baker, et al. (1999), used this nature of the minimum wage legislation and found that in Canada over the period of 1975-1993, a 10% increase of the teenage minimum wage is associated with a decrease of teenage employment of 2.5%. While this paper does look at teenage employment effects of minimum wage changes as opposed to young people, it’s results are still interesting as no other papers contradict its findings.

As has been shown, not all papers covering the same labour force find matching results. There are in fact large amounts of variation in the results of papers analysing the effects of changes in minimum wages in a given country, and there are several reasons for this. The main one is that different data is used to perform analyses in different papers. For instance, Abowd, et el. (1997b) uses longitudinal data when looking at the high rate of youth unemployment in France being caused by a rise in the minimum wage in the 1980s. However, Dolado, et al. (1996a) analysing the effect of the same change in wage, in the same country, over the same time period, used regional variation in minimum wages to establish the knock-on effect of the rise. They both, unsurprisingly, came to different conclusions of the effect that the change in minimum wage had on youth unemployment.

In order to analyse a specific example of youth unemployment being affected by minimum wage changes, a good case to analyse is that of France. Most countries mentioned so far have all used a similar policy for changes in the minimum wage – it is adjusted once per year, leading to a relatively small yearly increase, which will not majorly affect employers. This is also the case in France, however in 1981, after Francois Mitterand was elected as president, a 10% increase in the minimum wage was implemented. This provided a good analysis tool for Bazen and Skourias (1997b) to measure the effect of such a change on specifically youth unemployment. One key finding was that youth employment as a percentage of total employment in the workforce decreased, from 14.6% to 12.9%. One main possible explanation for this change is that employers preferred to hire low-paid, and more experienced older workers than young workers with little experience, who due to the increase in minimum wage, were now receiving a wage much closer to that of the adult minimum wage. The experience that the older workers had in this case would have made them better ‘value for money’ for the employers. Abowd, et al. (1997a) also looked at the effects of the 10% increase in minimum wage in 1981, and found that employment of young workers fell as a result. An interesting point that this paper adds, is that certain employment promotion programs, such as the TUC and the SIVP, were instigated at around the same time as the increase in minimum wage. These would have effectively protected employers from the increasing wages required to be paid to the young workers, and as such, a proportion of the young workers will have been protected from the rise in minimum wage risking their employment. The paper goes on to add however, that once the young workers were no longer eligible for such programs when the reach the age of 25, the probability of them becoming unemployed increased significantly.

The studies that have been looked at so far in this paper cover the effects of minimum wage on youth unemployment in developed countries. While it is not entirely relevant to this paper’s research question, studies looking into developing countries can also be interesting. The main difference between developed and developing countries is the notion of the covered and uncovered work – covered implies that it is a regular, paid job, which meets the minimum wage requirements. Uncovered means that the employee is still in a paid job, however, their wage is less than that of the minimum wage, normally, as they do not work the required weekly hours to be covered by the minimum wage. This point is mentioned by Pratomo (2016) in his study of the effect of the minimum wage on youth unemployment in Indonesia. On top of the cases of covered and uncovered employment, this research also includes the possible case of being an unpaid family worker. This paper leads to some interesting conclusions about the effect of an increase in the minimum wage. Firstly, it states that male youths, following a rise in the minimum wage, will have a lower probability of being employed in the covered sector, and will have an increased probability of being employed in the uncovered sector, being an unpaid family worker, or being unemployed. Having said this, the probability of being unemployed is higher than working in the uncovered sector or working as an unpaid family worker. On the contrary, when the minimum wage increases, young female workers also have a decreased probability of being employed in the covered sector, but have an increased probability of entering the self-employed sector and being unpaid family workers. It must be mentioned that the negative effect of being employed in the covered sector is slightly less for females than males, possibly as there are fewer females employed in the covered sector to begin with.

Overall, in contrast to developed countries, there is a slightly different effect of a minimum wage change on youth unemployment in developing countries. This is mainly due to the uncovered sector, which exists to a much smaller degree in developed countries than developing countries. When the minimum wage increases in a developing country, young workers can simply move to the uncovered sector, where they can be paid a lower wage, to match their perceived skill level, as mentioned earlier. This sector’s existence in developing countries is mainly due to weaker enforcement laws, as well as a lack of trade unions in developing countries – both of which are reason why an uncovered sector is not normally found in developed countries (Moretti and Perloff, 2000).

The aim of this research paper, as previously mentioned, is to investigate the effects of the minimum wage on specifically youth unemployment in the UK. Papers have previously looked into adult employment effects of the minimum wage in the UK, however interestingly, the area of youth unemployment has not received as much coverage. This is interesting as young workers are often those most affected by an increase in a minimum wage, and for this reason, many papers investigating countries other than the UK, look solely at youth unemployment as opposed to adult unemployment. Examples of these are (Baker et al., 1999) – covering Canada, and (Bazen and Skourias, 1997) – covering France, both of whom solely look at youth unemployment statistics. Despite many other countries having had such research carried out on their labour force, none has been done in the UK. This paper aims to fill that gap in the research and provide a link between youth unemployment and the minimum wage in the UK.

This paper’s research question is the following: Is it possible to increase the minimum wage in the UK, without increasing youth unemployment? The most appropriate methodology for carrying out this research will be using the “Difference in Differences” (DiD) approach, as the change in minimum wage will be treated as an exogenous shock to the economy (Azangue, 2013). In order for a DiD to be accurate, a control group is used to compare to the treated group. In the case of this paper’s research, the treated group will be the UK economy, while the control group will be a similar European economy, whose minimum wage did not change over the same period of analysis. The treatment of the UK economy will be the change in minimum wage.

Overall, this paper aims to fill a gap in research in the field labour economics, regarding youth unemployment in the UK and the minimum wage. The author believes that this is an important area which should be investigated more than it has been so far, as young workers are the first to be affected by an increase in minimum wages. In the case of the UK, minimum wages have been increasing at increased rates in the last two years, which make this topic very current, and just as important as discussions surrounding the minimum wage’s implementation in 1999.

Word count: 3666

Ashton, P. and Minford, P. (1996) Minimum Wages: A Macroeconomic Assessment. Available from: [Accessed 9 December 2016].

Azangue, A. (2013) Coping with the recent financial crisis, did inflation targeting make any difference?. SSRN Electronic Journal. Available from: https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00826277/document [Accessed 11 December 2016].

Bazen, S. and van Soest, A. (1994) Youth minimum wage rates: The Dutch experience. International Journal of Manpower, 15 (2/3), 100-117.

Chapple, S. (1997) Do minimum wages have an adverse impact on employment? Evidence from New Zealand. Available from: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.600.103&rep=rep1&type=pdf [Accessed 4 December 2016].

Gorry, A. (2013) Minimum wages and youth unemployment. European Economic Review, 64, 57-75. Available from: http://ac.els-cdn.com/S0014292113001104/1-s2.0-S0014292113001104-main.pdf?_tid=be991c44-bd92-11e6-bbe6-00000aab0f26&acdnat=1481235044_9222ba9856628965c16579330c9f2985 [Accessed 15 November 2016].

Gregg, P. (1992) From the sweatshop to the dole queue: The possible effects of a national minimum wage on employment and unemployment. Paper presented to Employment Service Conference on Unemployment in Context, March. Available from: [Accessed 23 November 2016].

Hashimoto, M. (1982) Minimum wage effects on training on the job. The American Economic Review, 72 (5), 1070-1087. Available from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/1812023.pdf [Accessed 18 November 2016].

Jimeno, J., Felgueroso, F. and Dolado, J. (1997) The effects of minimum bargained wages on earnings: Evidence from Spain. European Economic Review, 41 (s 3–5), 713–721. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0014292197000032 [Accessed 21 November 2016].

Kohen, A., Gilroy, C. and Brown, C. (1982) The effect of the minimum wage on employment and unemployment. Journal of Economic Literature, 20 (2), 487-528. Available from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2724487?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents [Accessed 3 December 2016].

Krueger, A. and Card, D. (1994) Minimum wages and employment: A case study of the fast-food industry in new jersey and Pennsylvania. Available from: http://davidcard.berkeley.edu/papers/njmin-aer.pdf [Accessed 15 November 2016].

Maloney, T. (1995) Does the adult minimum wage affect employment and unemployment in New Zealand?. New Zealand Economic Papers, 29 (1), 1-19.

Manning, A. and Dickens, R. (2004) Has the national minimum wage reduced UK wage inequality?. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society), 167 (4), 613-626.

Manning, A. and Machin, S. (1994) The effects of minimum wages on wage dispersion and employment: Evidence from the U.K. Wages councils. ILR Review, 47 (2), 319-329. Available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/2524423.pdf [Accessed 15 November 2016].

Manning, A. and Machin, S. (1996) Employment and the introduction of a minimum wage in Britain. The Economic Journal, 106 (436), 667-676. Available from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2235574?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents [Accessed 9 December 2016].

Manning, A. and Machin, S. (1997) Minimum wages and economic outcomes in Europe. European Economic Review, 41 (s 3–5), 733–742. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0014292197000329 [Accessed 9 December 2016].

Manning, A., Machin, S. and Dickens, R. (1994) The effects of minimum wages on employment: Theory and evidence from the US. National Bureau of Economic Research. Available from: http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/16931/1/16931.pdf [Accessed 15 November 2016].

Margolis, D., Lemieux, T., Kramarz, F. and Abowd, J. (1997) Minimum wages and youth employment in France and the United States. Available from: http://www.nber.org/papers/w6111 [Accessed 10 December 2016].

Metcalf, D. (1999) The British national minimum wage. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 37 (2), 171-201.

O’higgins, N. (2010) Youth unemployment and employment policy: A global perspective. Available from: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/23698/1/MPRA_paper_23698.pdf [Accessed 15 November 2016].

O’Higgins, N. (1997) The challenge of youth unemployment. International Social Security Review, 50 (4), 63-93.

ONS (2016) Unemployment. Office For National Statistics. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peoplenotinwork/unemployment [Accessed 13 December 2016].

ONS (2016) National minimum wage and national living wage rates. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/national-minimum-wage-rates [Accessed 21 November 2016].

ONS (2016) UK labour market: Nov 2016. Office For National Statistics. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/employmentandlabourmarket/peopleinwork/employmentandemployeetypes/bulletins/uklabourmarket/november2016#young-people-in-the-labour-market [Accessed 15 November 2016].

Perloff, J. and Moretti, E. (2000) Minimum wage laws lower some agricultural wages. Available from: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/51k1v5hf [Accessed 12 December 2016].

Pratomo, D. (2016) How does the minimum wage affect employment statuses of youths? Evidence of Indonesia. Journal of Economic Studies, 43 (2), 259-274.

Skourias, N. and Bazen, S. (1997) Is there a negative effect of minimum wages on youth employment in France?. European Economic Review, 41 (s 3–5), 723–732. Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0014292197000044 [Accessed 9 December 2016].

Stanger, S., Benjamin, D. and Baker, M. (1999) The highs and lows of the minimum wage effect: A Time‐Series Cross‐Section study of the Canadian law. Journal of Labor Economics, 17 (2), 318-350.

Stewart, M. (2004) The impact of the introduction of the U.K. Minimum wage on the employment probabilities of low-wage workers. Journal of the European Economic Association, 2 (1), 67-97.

Stigler, G. (1946) The economics of minimum wage legislation. The American Economic Review, 36 (3), 358-365. Available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/1801842.pdf [Accessed 15 November 2016].

Teulings, C., Margolis, D., Manning, A., Machin, S., Kramarz, F. and Dolado, J. (1996) The economic impact of minimum wages in Europe. Original Articles, 11 (23), 317-372. Available from: http://economicpolicy.oxfordjournals.org/content/11/23/317.abstract [Accessed 21 November 2016].

United Nations (2016) Unemployment rate of young people aged 15-24 years, each sex and total. Available from: http://mdgs.un.org/unsd/mdg/Metadata.aspx?IndicatorId=0&SeriesId=596 [Accessed 12 December 2016].

Vittorelli, C. and Cornu, P. (1996) LABORSTA Internet: Main statistics (annual) – unemployment (E). Available from: http://laborsta.ilo.org/applv8/data/c3e.html [Accessed 13 December 2016].

Barrett Fransen

Researcher’s name:

In case of students:

Panagiotis Giannarakis

Supervisor’s name:

Degree course:

Bsc Economics and Management Sciences

| Part 1 – Research activities |

| What do you intend to do? (Please provide a brief description of your study and details of your proposed methods.) |

You have to be 100% sure of the quality of your product to give a money-back guarantee. This describes us perfectly. Make sure that this guarantee is totally transparent.

Read moreEach paper is composed from scratch, according to your instructions. It is then checked by our plagiarism-detection software. There is no gap where plagiarism could squeeze in.

Read moreThanks to our free revisions, there is no way for you to be unsatisfied. We will work on your paper until you are completely happy with the result.

Read moreYour email is safe, as we store it according to international data protection rules. Your bank details are secure, as we use only reliable payment systems.

Read moreBy sending us your money, you buy the service we provide. Check out our terms and conditions if you prefer business talks to be laid out in official language.

Read more