“Availability or Entitlements: The East India Company and the Great Bengal Famine of 1770”

| Section 1: Introduction | 3 |

| 1.1 Background | 3 |

| 1.2 Historical Problems and Research Question | 4 |

| 1.3 Framework of Analysis | 5 |

| 1.4 Historiography: Availability or Entitlements | 7 |

| Section 2: Availability | 10 |

| 2.1 Background | 11 |

| 2.2 Method | 11 |

| 2.3 Data | 16 |

| 2.4 Analysis | 18 |

| Section 3: Who was affected? | 19 |

| 3.1 Method | 20 |

| 3.2 Data | 21 |

| 3.3 Analysis | 22 |

| Section 4: Entitlements | 25 |

| 4.1 Method | 26 |

| 4.2 Data | 27 |

| 4.2.1 Land Revenue Tax and Direct Entitlement Failure | 27 |

| 4.2.2 Land Re-consignment and Endowment Loss | 29 |

| 4.2.3 Exportation, Resource Stripping and Exchange Entitlement Failure | 30 |

| 4.2.4 Trade Restrictions and Trade Entitlement Failure | 32 |

| 4.3 Analysis | 34 |

| Section 5: Conclusions | 35 |

| 5.1 A Summary | 35 |

| 5.2 What do these findings tell us? | 37 |

| Bibliography | 38 |

Section 1: Introduction

This paper examines famine in India under British Merchant rule, and what role, if any, British economic actors played in the Great Bengal Famine of 1770. It also explores the limitations of economic actors as political entities; and seeks to reconcile preconceived notions of the role British institutions played in the crisis with the quantitative reality. Throughout, it will be argued that previous works in the famine literature have overestimated the role of British institutions in the crisis, tending to analyse the event as though it occurred in a vacuum. This study contributes to three research fields: the economic history of India, the study of famine through an economic lens, and the history of British Institutions as colonial powers. To do this, it utilises both quantitative data and qualitative accounts collected in Britain, India and on a global scale.

1.1 Background

The Great Bengal Famine of 1770, referred to as the ‘Chiyattorer Monnontor’ in Bengali, was ongoing between the years 1769 and 1773, and affected those regions within the remit of the lower Gangetic plains of India. The locality, then known as Bengal, includes the modern Indian states of Bihar, West Bengal, Odisha, and Jharkhand, and Dacca; which form part of modern-day Bangladesh. Estimated to have resulted in the deaths of up to 10 million people, the famine occurred only six years after the East India Company became the de-facto ruler of Bengal; as following the Battle of Plassey in 1757, and Buxar in 1764, a treaty saw the Company receive taxation rights (diwani) for the region. However, although in 1766 the EIC disbanded the Nawab’s troops, in 1770 he was still at least the de jure head of the political affairs of Bengal; that is, there existed a shifting balance of power between the EIC and the Nawab – one which did not escape the minds of the region’s landlords. Thus there was significant distrust between the Company and the major landlords of Bengal before and during the famine of 1770. What is perhaps most indicative, however, is that this dissention was significant enough that the EIC expended enormous resources on monitoring costs throughout the famine period (Roy, 2012), increasing defence spending, appointing supervisors to overlook revenue collections in various districts (1769) and dismissing the Nawab’s agents or faujdars from those districts (1770) (Bayly, 1983). Hence there is a two-fold issue here; firstly, the EIC was increasing spending in multiple spheres – which, of course, involves employing people. Secondly, given the famine began in ’69, during the period in which the famine occurred Bengal was experiencing an administrative transition. That is, the EIC had not yet solidified their position as the de facto rulers of the region, and were primarily responsible only for revenue collection.

1.2 Historical Problems and the Research Question

Aside from explaining a period of economic history, Sen’s (1981) analysis of famine in India – including the 1770 famine – resulted in the complete reorientation of contemporary famine studies from a Malthusian model to a distributive one. His analysis of the Bengal famine in 1943-44 in particular was readily accepted, as it matched the official inquiry published in 1945; which claimed that the famine did not occur as the result of a decline in availability, rather, by hoarding and speculation and a lack of trade entitlements (the ability to exchange goods). Sen highlighted how this market failure, in the form of a failure in exchange entitlement mappings, compounded inaction on the British Colonial government’s part; those who, in his opinion, should have intervened and halted speculatory price rises and distributive inefficiencies. Beyond the reorientation of contemporary famine studies away from a Malthusian model of scarcity, Sen’s work also redefined the lens through which famine historians review past events and price shocks – notably, when Davis (2000) referred to nineteenth century tropical famines as ‘man-made events’ he specifically meant ‘made-by-the-colonial-state’ (Roy, 2016). It should thus be noted that this trend in the literature, away from Malthusian assessment and towards a ‘man made by colonial invaders’ view of famine, may be a cautionary tale; as more recent work, such as O’Grada (2007), has noted that both the official report and Sen’s work are not consistent with the quantitative reality, demonstrating that the 1945 report published by the enquiry was an attempt by colonial rulers to avoid diverting shipping and food supplies from the ongoing war effort. This debate has implications for whether or not the reorientation away from food scarcity in famine studies – a relevant topic in today’s world – is justified.

When analysing the particularities of famine, the literature tends to fall broadly into the rather ambiguous categories of ‘manmade’ and ‘natural’ events; though often without rigorously defining either term (unlike the oft contested criteria for defining famine itself). A notable exception is O’Grada (2009), who offers a historiographical assessment of their usage, which certainly reveals a trend of commonality. That is, there exists a tendency to aggregate together those ‘manmade’ events, without accounting for differences in causality on the part of the affected, policy makers, or external actors. Generally, when referring to a famine event as ‘natural’, academics are specifically referring to the Malthusian definition; wherein sudden food shortages occur, often due to harvest failure, and have dramatic consequences. Perhaps due to long term malnutrition in the region, or perhaps due to excessive rates of reproduction. This narrow definition juxtaposes sharply with that which may be termed ‘manmade’. It is true that the modern definition of ‘manmade’ is often in reference to some state action that diverts food from one group to another, or political inaction that prevents rapid response and relief mechanisms – most often seen during times of war (Bengal, 1943), or despotic regimes (North Korea, 1995-98). However, as O’Grada (2009) reveals, the term has and may also be applied to the actions of non-state private actors, to the ill advised actions of the affected individuals – in terms of panic or speculation, and to natural economic processes that may hinder an individual’s economic exchange ability to trade for the goods he or she requires, such as sudden or long term structural unemployment in a region.

In light of the findings of other revisionists of Sen’s work, and using newly available quantitative data, I will investigate whether or not the rhetoric surrounding 1770 Bengal famine also requires revision; by re-examining evidence within Sen’s own framework of famine analysis. I shall also address the topical literature in much the same way as I intend to investigate the 1770 famine itself; by using the framework of famine assessment laid out by Sen (1981), to avoid the aforementioned tendency to discuss those ‘man-made’ causes without systematically differentiating between those culpable.

1.3 Analytical Framework

In “Ingredients of Famine Analysis: Availability and Entitlements” (1981) Sen outlined a theoretical framework by which he thought famines should be analysed; that is, to answer whether a) there was a substantial food availability decline compared with normal supply, b) to which occupation groups did the famine victims chiefly belong, and c) did these groups suffer from substantial entitlement declines, and if so, what were the characteristics of these entitlement failures?

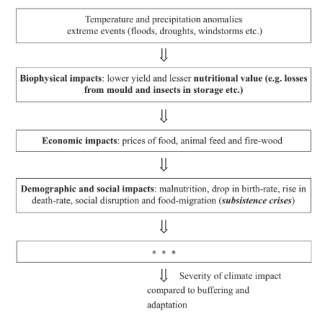

Food availability decline, (henceforth referred to as FAD), was the foremost view of famine prior to Sen’s publication of his framework in 1981; which directed the study of famine away from a Malthusian-type analysis, and towards the discussion of market failure. This FAD approach was very much embedded within the ecological narrative, and so much of the pre-1980’s famine literature focused on supply shocks via a climate impact mechanism (see Figure 1.1). According to Sen, the FAD approach may be summarised as thus; famines occur following a food availability decline, such that aggregate food supplies to do not exist in sufficient quantities to meet the nutritional needs of a given population. No matter the cause of this FAD, the crux of the argument is that there is not sufficient food available.

Figure 1.1: Pfister and Brázdil (2006), modelled after Kates (1985)

Sen, however, noted that in the case of several famines that whilst it is true an initial food availability decline may have occurred, the impact of this decline was felt unequally by the population of a given polity. That is, it may have affected only those of the lower classes, or only those working in a particular industry. Furthermore, he highlighted that famines may occur even when a general FAD does not exist; that is, there is sufficient food available in a given region to meet the nutritional needs of the entire populace, but certain groups within society may no longer have the ability to ‘command’ this food. Thus the exchange entitlement approach, as outlined by Sen (1981), is based not on the relative availability of food, rather, on the ability of those individuals within an economy to command it through the legal means available to them. It concentrates on each individual’s entitlement to commodity bundles, which of course include food, and implies that starvation will occur wherever someone is not entitled to a particular bundle with sufficient food.

If E is the entitlement set of a particular individual i in a given society, and consists of a number of commodity bundles individual i may choose between; then in an economy with property rights and trade (exchange with others), and production (exchange with nature), E thus depends on two parameters; the individual i’s endowment (the ownership bundle), and the exchange entitlement mapping. The exchange entitlement mapping, or E-mapping, specifies the exchange entitlement set of alternative commodity bundles respectively for each endowment bundle, and will depend on the legal, political, economic and social characteristics of the society in question and the person’s position within it. Entitlement failure may thus occur wherever there is an endowment loss or a failure of production, or, if there is an exchange entitlement failure, due to variables such as an increase in the price of food, or a fall in relative wages etc. Sen (ibid.) further highlights that as an extension of the endowment loss vs. unfavourable shift in entitlement mapping approach; it may be beneficial to view an entitlement failure as a trade failure, or, as a direct entitlement failure. The former may be a reduced ability to trade due to a change in legislation, a real wage decrease, or a breakdown of the market mechanism, whereas a direct entitlement failure may occur in the form of a reduced endowment or production capability; though he notes that in more developed economies these often go hand in hand, given that particularly agrarian land workers may produce a commodity both for consumption, and which will be traded with others in order to purchase some other food.

Thus the first question attempts to identify proximate causes of a given famine, that is, was there a supply shock effect, whilst the latter two attempt to disaggregate the degree of exposure by individual population group. Sen’s framework has been extremely influential since the time of its publication; primarily, because it alleviates the impact of the ‘natural as ecological’ narrative, and reframes inequality as the ability of individuals to command food during a time of crisis. In this paper I will methodologically assess the three questions outlined by the framework; using both quantitative data and eyewitness testimonies to motivate my answer, as to whether or not the proximate causes were availability, and thus supply shocks, or entitlement failures.

1.4 Historiography: Availability or Entitlements

There are multiple contested views on the origins and causes of the Bengal famine of 1770; most notably, between those who cite the supply-shock effects of consecutive years of drought on a population made vulnerable by subsistence farming of the Malthusian kind, and those who claim entitlement failures were responsible, such as Amartya Sen. Sen in particular claimed that no previous famine had occurred in India that century, and concluded that it was entitlement failures, as a result of EIC policies, which caused problems with the distribution of resources. According to Sen, these took the particular form of direct entitlement failures, as the EIC destroyed large areas of food crops to make way for the growing of indigo plants for dye and opium poppies, and increased the tax on agricultural produce from 10% to 50% – thus reducing the native Bengali’s ‘endowments’. Sen claims that this resulted in the transfer of much of Bengal’s wealth to the company’s shareholders, and that the resulting food shortage was further aggravated by the nonresponsive administration of the EIC – which was concerned only with extracting wealth from the region regardless of the cost in lives. That is, there was a sufficient food supply provided the EIC had responded appropriately. However, Tirthanka Roy, one of the foremost contemporary academics in the field of Indian economic history, has, in multiple works, referred to 1770 and other famines as the result of ongoing environmental factors inherent to India’s ecology (2016, 2012). That is, ecological crisis and a resulting food shortage caused the famine, not British interference. Nonetheless, whilst Roy does not claim that a supply shock as a result of ecological crisis was the only contributing factor, in multiple works he has criticised Sen’s dismissal of supply shock factors. For example, the impact of two years of erratic rainfall preceding the famine event – leading to a reduction in crop yields, which was further compounded by the impact of a smallpox epidemic on human capital productivity. He has also referenced geographical constraints outside of the political sphere; such as the inability to overcome local-level supply shocks through trade (McAlpin, 1979), because of problems with transportation over long distances prior to the development of a comprehensive intra-provincial railroad system (2016, 2012). Damodaran (2007), however, whilst also falling under the availability side of the debate, disagrees with Roy on several key issues. In particular, he criticises the McAlpin (1779) study, asserting that in the case of the 1770 famine it was a combination of geographical factors, including ‘the gradual erosion of traditional systems of subsistence and its ecological basis, access to common lands, trees etc.’ which were responsible for creating a crisis. In short, in the wake of commercialization, there had been an attempt made by land-holders to move away from Malthusian-type subsistence lifestyle and farming practices; which we know is not feasible without a concurrent technological shift. Thus they had exceeded the capacity of their agrarian economy and limited resources, and subsequent crop failure leading to a supply shock was inevitable.

Conversely, McAlpin (1983, 1979) claimed that a mitigating factor in famine prevention exists in the form of growth of trade; though she used other famines as her case studies for such an analysis, primarily the Deccan famines of the 19th Century. Though Roy has cited McAlpin’s findings in discussion of the 1770 famine, Damodaran would disagree with the idea that such a micro-scale issue, geographical constraints preventing the market from moving grain in sufficient quantities over the large Deccan region, may be applied to the earlier 1770 Bengal famine. However, whilst Damodaran may have raised valid concerns about the generalisability of McAlpin’s findings in his 2007 paper, Roy’s (2016) reference to her work served a secondary purpose; and one particularly telling in regards to the 1770 famine. That is, more recent work than Damodaran (2007) in fact supports the general themes of McAlpin’s work; and the examples Roy (2016) cites are Burgess and Donaldson (2010), and Studer (2015). Burgess and Donaldson (2010) found that ‘rainfall shortages had large effects on famine intensity in an average district before it was penetrated by India’s expanding railroad network, but the ability of rainfall shortages to cause famine disappeared almost completely after the arrival of railroads’. Similarly, Studer (2015) found that price correlations between market sites were lower in India for similar distances than in Europe in the eighteenth and early nineteenth century, suggesting that ‘trade networks and market structures were shaped by geography more directly than by political boundaries’ in both regions, and that ‘nature burdened India with more hurdles to overcome.’ These findings, aside from supporting the conclusions previously drawn by McAlpin (1979) – that reduced costs of trade, or the ‘openness’ of agricultural producers to trade, mitigated famines – also provide evidence for the counterfactual; and one that is important in the case of the 1770 famine. That is, if internally integrated markets may have mitigated famines in the twentieth century, openness did not worsen famines in the eighteenth century.

Whereas classical liberal economists advocated free trade – and in the case of Smith, Malthus and Mill, did so throughout the nineteenth century – during this time many famines occurred within the jurisdiction of the British Empire. Thus Indian nationalists like Sen contended that free trade made famines more likely, and weakened the relief effort. However, if the findings of Studer, McAlpin, Burgess and Donaldson hold true, then, despite the fact their work assessed availability impacts and their proximate causes, they also provide strong support for a counterfactual point that sharply contradicts the precise form that Sen believes entitlement failures took in the case of the 1770 famine. In principle, if in the latter years trade mitigated famines, then the premise that increased trade with Britain through the EIC, one of the primary factors that Sen blames for entitlement failures – as food was diverted abroad for consumption – is perhaps increasingly questionable without also acknowledging that there must have been a severe concurrent supply shock. That is not to say that Sen represents the entirety of the so called ‘entitlements’ view; indeed, there are others who would technically fall under that label as defined by Sen (1981), yet who would disagree with the idea that food exports were a significant factor, or indeed, with Sen himself.

However this may stem from a misunderstanding of Sen’s writing; for example, the interpretation by Devereux (1988) of entitlements as solely a demand side explanation fundamentally opposed the supply side assessment of food availability decline. Perhaps the most comprehensive assessment of the entitlements aspect of Sen’s framework is Ravallion (1997), who offers an addendum to Sen’s theoretical framework that acts as an extension rather than an amendment, that is, a discussion of vulnerability to famine. Although far from the first to mention vulnerability, as Brázdil has based numerous works on the issue, though often from a climate vulnerability angle, Ravallion specifically refers it back to Sen’s framework in the context of India. According to Ravallion (ibid.), at a more aggregate level we are able to assess the precise causes of vulnerability to entitlement failure, and these may come in the form of a ‘weak social and physical infrastructure, weak unprepared government, and a relatively closed political regime’. Thus whilst not directly contradicting Sen’s entitlements assessment of the 1770 famine, as many who focus on the availability side are wont to do outright, Ravallion offers a line of enquiry for within the entitlements camp that may lead to contention with Sen’s own views; particularly in regards to the famine of 1770. To what extent can you fundamentally blame a joint stock corporation for ‘causing’ a famine within the area it operates, without first assessing its ability to react to a famine event, nor discussing whether it had the moral obligation to do so? Particularly if those inabilities were compounded by geographical or some other inherent factors?

What is clear, in terms of previous literature surrounding the 1770 famine, is that local-scale issues derived from the analysis of one famine may not necessarily hold as proximate causes of any other; particularly in regards to different regions, with different geographical endowments. Also notable, is that Sen’s theory of price shocks without a preceding supply shock – leading to a decline real wages in terms of food prices – does not offer a generalisable hypothesis as to why this may occur. There thus exists a disconnect within the contemporary literature; between those Bengal-specific availability constraints, and potential failures in the years preceding the 1770 famine, and those Bengal-specific socio-political factors which may have affected entitlements. This paper thus seeks to reconcile the two into a cohesive whole.

Section 2: Availability

Both the literature surrounding the Great Bengal Famine of 1770 (’69 – ’73), and contemporary accounts by Company officials, tend to agree that there was an initial shortfall of agricultural output at the beginning of the famine event. Though most sources are qualitative accounts, and no rigorously calculated official output figures are available. What is more contentious, however, is whether or not the initial shortfall in agricultural output was significant enough so as to have enacted a famine of such an extreme experienced by the districts of Bengal in the years 1769 – 1773. Some historians, both economic and otherwise, have alluded to the idea that if storages of grain had been correctly managed and distributed, this should have alleviated the worst of the crisis (see Mukherjee, 2011, and Parthasarathi, 2011). Thus Sen’s framework requires that we first examine precisely what form the agricultural shortfalls took, the impact of shortages on prices, and to identify whether or not we can conclusively determine agricultural shortfall caused a sufficient dearth so as to result in famine.

2.1 Background

In the years preceding the famine there were a number of climatological shocks that affected agricultural output, and throughout the famine event, a number of occurrences may have contributed to its longevity. The famine itself was preceded by a partial crop failure in the agricultural year ‘68/’69, which followed the monsoon failure experienced by Bengal and Bihar in 1768 (Grove, 2003). This crop failure was compounded by a subsequent failure of the monsoon in 1769, and contemporary accounts describe the impact of this rain failure, with the native superintendent of Bishnupur reporting that by September 1769; “the fields of rice had become like fields of dried straw” (Hunter, 1868). Thus follows reports on the following ‘69/’70 agricultural year, wherein officials note that; “during the 1770 famine not a drop of rain had fallen in most of the districts [of Bengal] for six months” (Campbell, Sessional Papers, 1878, pp. 455 – 66). Furthermore, official reports describing the catastrophe reported that by; “June 1770, the Resident at the Durbar confirmed that the living were feeding on the dead” (McLane, 2002, pp. 194). Issues compounding the longevity of the famine event are more controversial, though the most common cited includes those disease which commonly accompany famine; such as pestilence, and the outbreak of smallpox that particularly affected Murshidabad (Sen, S., 2010, pp. 43). Ongoing disease combined with the loss of life from the initial dearth, meant that by the time rain fell in a sufficient quantity, during late 1770 there was an insufficient labour supply, particularly in some regions, to attain the maximum possible agricultural output for the ‘70/’71 agricultural year (Damodaran, 2007). It was only in 1771, at the beginning of the usual cultivation season, that the administration discovered the remnant population was not of a sufficient size to till the land (ibid.), and this was further compounded by flooding in some regions which damaged standing crops. Thus despite the regular return of the monsoon rains, other shortfalls occurred in the following years until ’73; which raised the total death toll above that of the height of the famine in 69/70.

2.2 Method

We can thus begin as Sen (1981) does in regards to case studies of the Bengal Famine of 1943, and the Ethiopian Famine of DATE; by examining the impact on prices during the famine event. Though this, of course, does not indicate whether or not any grain storages were misappropriated, or whether there was some other mechanism aside from a decline in agricultural output which may have affected availability. However, in terms of economic impact, we can observe that the price of common aus rice, the primary food source for much of the region, rose on average throughout the Bengal province across the famine period. The wholesale price of rice, measured in rupees per ‘maund’, rose from Rs. 1.77 in the year preceding the first reported agricultural shortfall in 1768, to Rs. 3.82 in the year following the reported crop failure of ‘69, and above Rs. 8.64 by the height of the famine in 1771 (Table 2.1).

Table 2.1: Wholesale Price of Rice in Bengal, 1767 – 1774 (rupees per maund)

| Year | Price (rs.) Common Rice | Index |

| 1767 | 1.77 | 100 |

| 1768 | 1.93 | 109.04 |

| 1769 | 2.48 | 140.11 |

| 1770 | 3.82 | 215.82 |

| 1771 | 8.64 | 488.14 |

| 1772 | 2.32 | 131.07 |

| 1773 | 2.08 | 117.51 |

| 1774 | 1.7 | 96.05 |

| Notes: Price quotations are taken from the Global Prices and Incomes History Group database; “India prices and wages 1595-1930”, Allen and Studer. | ||

There is a similar trend to be observed in the markets for other commodities, and other types of rice farmed at different times throughout the year; and we can identify a price shock of a similar magnitude in the prices of common rice, the staple diet of the rural poor, and fine rice, commonly produced by those working the land to be sold to the upper classes. However, as data is sparse for the region in this period, the Allen and Studer database has no figures for the Bengali average of fine rice prices, nor Calcutta, the regions capital. We do, however, have data for Chinsurah; a town north of Calcutta (Table 2.2). What is immediately apparent is that not only do prices of rice in Chinsurah peak a year earlier than the Bengali un-weighted average, in 1770 as opposed to 1771, but that the starting prices pre-famine were also much higher in Chinsurah. This will be discussed in detail in Section 3. This sharp rise in commodity prices is consistent with what we know about supply shocks, and previous liturgical work on the Bengal famine; – a sharp price rise occurs, reducing real wages and thus purchasing power, causing starvation and malnutrition. However, much of the literature surrounding the Bengal famine has used price data alone to illustrate said supply shock; drawing tenuous links between the rise in prices and a fall in supply due to harvest failure, based on contemporary descriptions of abnormal rainfall in the two years prior to the famine event.

Table 2.2: Wholesale Price of Rice in Chinsurah, 1767 – 1774 (rupees per maund)

| Year | Price (rs.) | Index | Price (rs.) | Index |

| Common Rice | Fine Rice | |||

| 1768 | 2.96 | 100 | 3.71 | 100 |

| 1769 | 3.64 | 122.973 | 4 | 107.8167 |

| 1770 | 12.31 | 415.8784 | 13.33 | 359.2992 |

| 1771 | 1.67 | 56.41892 | 2.11 | 56.87332 |

| 1772 | 1.18 | 39.86486 | 1.74 | 46.90027 |

| 1773 | 1.29 | 43.58108 | 1.38 | 37.19677 |

| 1774 | 1.25 | 42.22973 | 1.43 | 38.54447 |

However, relying on price data alone does not allow us to conclusively differentiate between availability and entitlement failure; given that we would expect other proximate causes of famine, including Sen’s (1981) theory of speculation, to enact a price rise – with or without a concurrent supply shock. Indeed, Sen himself highlights that a supply shock does not necessary premeditate a price shock; as these may occur even where there is a relatively abundant, if mismanaged, supply. He would thus argue that the observed increases in commodity prices occurred for some entitlement reason, and not because of an availability decline as the result of climate impact on the biophysical sphere. Conversely, although we do not have quantitative records of crop yields from across the famine period, and we are thus limited in that regard, there exist numerous pieces of anecdotal evidence and contemporary accounts which evidence that a substantial decline in supply occurred during the famine years. Aside from contemporary estimates, which place intra-regional agricultural shortfall between 50% (WBSA, Proceedings, 1770, pp.444) and 28% (BDR, Firminger ed., 1923), we also have the following (which makes reference to the comments by the native superintendent of Bishnupur discussed in 2.1), taken from the Proceedings of the Select Committee Secret Consultation, 7 February, 1769:

“The year 1769-1770 was marked by a period of remarkably scanty rainfall. It was reported that the field of rice parched by the heat of sun were like fields of dried straw and that land became as hard and dry as a piece of rock and the labourers were unable to till it with the plough. As a result, no crop could be produced. Not only the rice harvest, but wheat was also badly damaged.”

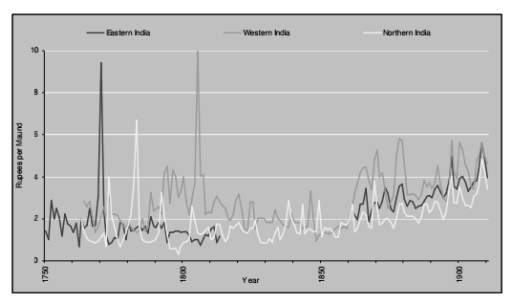

Furthermore, the excessive rainfall in the year 1770 – 1771 did not relieve the people from the preceding drought; rather, it caused overflowing of rivers and damaged standing crops. Thus the impact of the drought-driven famine of ’69 was prolonged right up until the harvest of ’73. Thus is it enough to note a change in climate that is consistent with reports of a lower crop yield with no specific output figures? Evidence for other regions supports this, as Bengal was not the only region within the Indian sub-continent to suffer price shocks in certain markets around the timing of the famine event. The co-movement of prices in Figure 2.2 is particularly interesting, as Studer (2008) concluded that, prior to the mid-19th century, there was only limited market integration across the Indian sub-continent; and that the grain trade in the years prior was primarily local.

Figure 2.1: Wheat price series for the different major regions in India between 1750 and 1914

From “India and the great divergence: assessing the efficiency of grain markets in 18th and 19th century India”, Studer, R. (2008)

Indeed, he noted that co-movements in price series only occurred on an intra-provincial basis, and when rare inter-provincial co-movements did occur, ‘adjustment processes to spatial price differentials were slow’ (ibid.). The degree to which the price shock varies is also possibly significant, as in the North the price shock is comparatively smaller than the East. This is to be expected if we are making specific reference to a supply shock, as though rainfall is still necessary for agricultural production in the North, they are far less reliant on monsoon rain than the East. Conversely, in the East the effect on grain prices was dramatic, perhaps initially aided by increased demand from a substitution effect after the failure of the rice crop, whereas the North primarily relied on less water intensive grains due to its higher elevation. We know that the monsoon has been of key importance in Indian history; according to Peers (2006, pp.12);

“The volume of rainfall that came with the monsoon, and its timings, were two important determinants of the kinds of crops that were grown, as well as their yield. A third factor is the predictability of the monsoon rains: some regions of India like Bengal not only could expect more rain but also could rely on the regular appearance of the monsoon (but should it fail, as it occasionally did, disaster was the usual outcome.) Elsewhere in India, in the Deccan for example, where monsoons were not so reliable, farmers turned to irrigation or the construction of tanks to forestall the threat of drought.”

Thus not only was Bengal’s primary crop heavily water-intensive, and hence reliant on the monsoon, but there are also entrenchments issues and sunk costs in terms of asset specificity; if the arrival of the monsoon had been predictably regular for a long time prior, not only had Bengal become overly dependent on rice production, and thus vulnerable to crop failure, but they lacked the investment in famine prevention technology of the Deccan, where monsoons were less reliable. When using price data to establish whether or not a significant shortfall in supply occurred, the following report, from the IOR Bengal Board of Revenue (1974), offers further insight in to precisely what pattern we should observe in the data:

“Bengal’s agriculture was dominated by rice growing. A good water supply was crucial for the success and quality of the crop. In low-lying areas assured of abundant floodwater, the main crop in western Bengal, as elsewhere, was the high-yielding ‘aman’ rice; which was harvested in the winter to provide fine quality rice. Poorer cultivators did not grow aman rice for their own consumption, rather, for sale. In areas of a higher elevation, where prolonged immersion could not be guaranteed, ‘aus’ rice was the staple food; this grain, produced in the autumn, was of both a lower yield and quality, and was thus relied upon by the poorer classes. In favourable conditions, the autumn aus harvest could be followed by another crop of winter aman rice. Otherwise, good quality land used for the lower quality aus rice would be reused in the winter for crops like cotton and mustard seed for oil. Pulses such as lentils (daal) and coarse grains like millet eaten by the poor and used as animal feed were either grown interspersed with rice or as another winter-sown crop. Sugarcane took up the ground for the rest of the year.”

Here then, are several conditions by which we may establish whether or not a supply shock occurred, using contemporary price data for various commodities. If the lack of rainfall was sufficient to cause a supply shock in terms of lower quality common aus rice, we should also see a similar price spike for the higher quality aman – which was not consumed by the poorer classes, but grown and sold to the upper classes. This is particularly significant, as given the greater water requirements of the fine rice we would first expect to see an impact on the fine rice yield, following the partial monsoon failure of ’68, before we see an impact for the less water-intensive common rice. Similarly, a failed crop of common rice in the autumn would also mean a lower yield of other commodities such as cotton, mustard seed, pulses and lentils, which would, in the normal way, be planted after the rice harvest and cultivated during the winter. Given sugarcane took up the available land for the rest of the year, we should see a price shock in the market for sugar cane in the period following a price shock in the common rice market if, indeed, the price shock occurred because of a supply shock. We can therefore look at the impact on prices in these key commodity markets across the famine event, as the timings of any price shock are key to differentiating between a speculatory price rise in the market of a particular commodity, and a common agricultural shortfall in all water-reliant crops.

2.3 Data

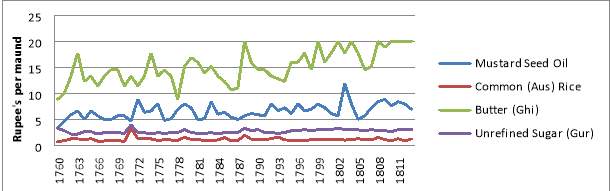

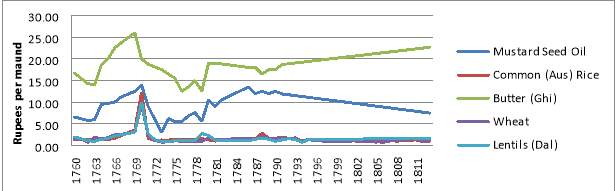

The following projections were all created using data from the Global Prices and Incomes History Group, “India prices and wages 1595-1930”, contributed by Allen and Studer.

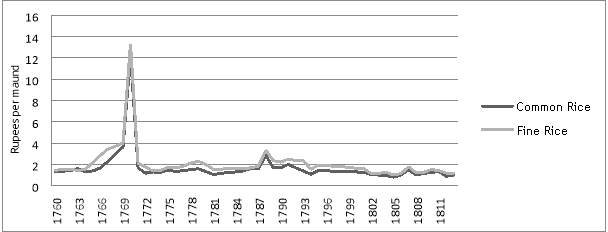

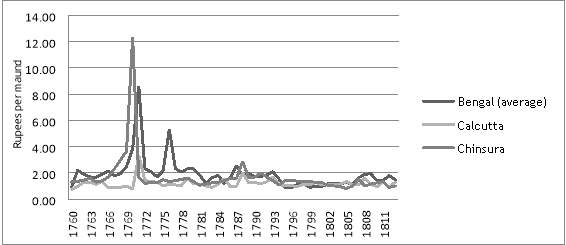

Figure 2.2: Common and Fine Rice Prices in Chinsurah 1760 – 1813

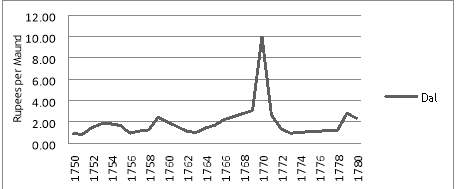

Figure 2.2 shows the prices of common and fine rice from the period 1760 – 1813, and what is immediately apparent, is the lag in price increase over the famine period for common compared to fine rice. Given the ‘supply shock’ explanation relies upon the monsoon failure for successive years prior to the famine, the data here does support this; as it evidences the impact occurring first in the fine rice market the year prior to the impact in the less water intensive common rice market the following autumn. In terms of the second criteria outlined in Section 2.2, that if a drought occurred, a failed crop of common rice in the autumn should be followed by a lower yield of other commodities planted in the winter. Figure 2.3 shows the price of dal, lentils, across the famine period; a crop which is grown interspersed with the autumn rice harvest, and also sewn as a winter crop. It demonstrates a slow rise in the price of lentils in the years 1768 and 1769, followed by a sharp price increase in 1770. This is consistent with what we would expect to see if it were a supply shock causing the observed price shocks – a small increase following the agricultural shortfall of ’68, followed by a slightly higher price increase in 69’ when the monsoon failed to materialise and the autumn rice crops failed, and a subsequent price spike in 1770 when the winter plantation of dal to be harvested in the spring instead withered in the fields.

Figure 2.3: Price of Dal in Chinsurah 1750 – 1780

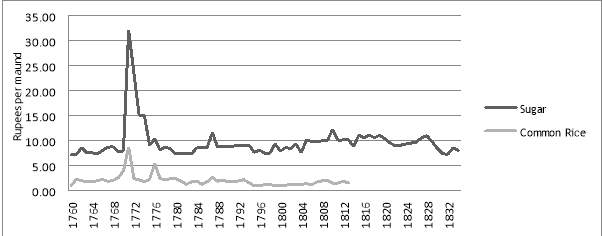

Figure 2.4: Average Sugar and Common Rice Prices in Bengal 1760 – 1834

Finally, given that sugarcane was planted for the rest of the year from spring onwards, following the harvest of both common and fine rice, we would expect to see a price shock in the market for sugar with a time delay, if the price shock were to indicate some sort of supply shock. In Figure 2.4 not only do we see a gradual price increase in common rice beginning at the end of 1768, but the data supports our hypothesis as outlined in Section 2.2. Following the price spike in the market for common rice after the failed ’69 harvest, there is a sudden price shock in the market for sugar which would indicate a subsequent failed sugar harvest in 1770. What is of key importance, however, is that the above average price of common rice in Bengal may be obscuring a regional effect; as within the market for common rice, there exist price differentials between Calcutta, the region’s capital, and Chinsurah. This is not an isolated incident, and we see a similar trend in the prices of various commodities.

Figure 2.5: Common Rice Prices in Bengal 1760 – 1813

What is interesting in regards to the market for common rice, however, is that referring to Figure 2.5, we see that although both Calcutta and Chinsurah see a price shock during the famine period (’69 – ’73), the impact is much more immediate in Chinsurah; and of a far greater magnitude. In fact, it seems to be a common trend that Calcutta is the least affected by price shocks in the markets for most commodities. This may be explained in a number of ways; i.e. that Chinsurah was a far poorer region, and hence relied heavily on common rice farming and the crops planted following its harvest. Or perhaps, that as a port city Calcutta had much more immediate access to ancillary supplies of grain imported from other regions. This will be addressed in detail in Section 3.

2.3 Analysis

In this section we have thus identified the forms agricultural shortfalls as a result of monsoon failure took, those water-intensive crops reliant on the regular rainfall pattern, and the impact on prices throughout the famine event. However, given the lack of agricultural output data we cannot conclusively determine that the agricultural shortfall caused a sufficient dearth so as to result in famine, nor can we ignore the possible implications of non-climate effects on availability; given that a number of scholars cite issues with policies regarding the storage of grain in granaries as being of key importance to exacerbating the impact of an agricultural shortfall. Furthermore, price data alone does not allow us to conclusively differentiate between the proximate causes of an availability decline; given the ongoing debate surrounding the reduction in land designated for agricultural cultivation in favour of the production of so called ‘cash crops’. For example, Chaudhury (1995) evidenced that in the years prior to the famine there was a destruction of food crops on the part of the EIC, in order to clear the land for the cultivation of opium poppies. A reduction in food supply from non-environmental means would have also resulted in an availability decline, and so this must be re-examined in Section 4.

Section 3: Who was affected?

Thus far the focus of this paper has been on the availability of food, and whether or not we can conclusively say that there was a food availability decline (FAD) during the Great Bengal Famine of 1770. However, in order to give a comprehensive analysis of the famine event, the framework proposed by Sen (1981) requires the identification of whom, precisely, the famine victims were. Which occupation groups did they belong to? Was the famine was a widespread phenomenon which affected the whole province equally? Thus what the previous section has not yet established, is who was affected by the fall in general availability and subsequent price shock, and whether or not one group or another was affected to a greater or lesser extent.Whilst it is true that during times of famine there is said to be widespread starvation following dearth, it does not necessarily hold that all groups within a given society will suffer equally; this may be for a number of reasons, including but not limited to Sen’s entitlement debate; wherein different groups may have different powers to command food, and thus a general shortage may highlight these contrasting powers. Furthermore, inter-group distributional issues may not only occur because of differing abilities to command food during a time of crisis, but also because the initial FAD has a greater impact on those populations more vulnerable to starvation.In the case of Bengal, different areas within the province may have been initially more vulnerable to a supply shock; whereas we know from Section 2.2 that different regions of India receive different amounts of rainfall in the average year, even within the Eastern province of Bengal there is geographical disparity between the North, East and South of the province, and the Western and Central locales. The lowlands of Bengal were predominantly agrarian, with an estimated two-thirds of the population involved in the production of primarily rice, as well as other grain, lentils (dal) and pulses. This left the cultivators extremely vulnerable to a shift in climate given the water intensive nature of their crop; and due to asset specificity in terms of land, farming techniques, and resources, in case of crop failure in a given year, the rice tracts had no other substitute crop to fall back on. Given the aforementioned issue in Section 2.1, wherein regular arrival of the monsoon meant little innovation had been undertaken as in the Deccan, for times when the rain did fail, this was further compounded by the fact the population was almost entirely dependent on regular and sufficient rainfall. When a deficiency in the supply or distribution of the monsoon rains did occur, there followed a shortfall in the agricultural output for that agrarian calendar year (given the Bengali calendar begins and ends during the dry season, in Gregorian April).In 18th century Bengal, the distribution of people throughout the province was also based on social strata; those hereditary revenue collectors that were the relic of the Mughal empire that had not yet ceded de facto rule to the British, and the broad base of cultivators which included landless labourers and sharecroppers. According to Marshall (1987), there also existed a large artisanal class, as indicated by census data from a village just outside Calcutta that had 19 coppersmiths, 66 carpenters, 40 silversmiths, 41 oilmen and 180 weavers. However, these artisanal and merchant classes often resided in agrarian areas, and were thus also reliant on the rural economy; as such, if any shortage were to occur, it negatively affected the majority of the populace, with only the upper classes in the major cities, and those in their employment, insulated from scarcity.

3.1 Method

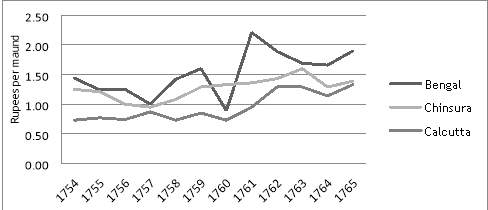

Prior to the ensuing discussion, however, we must first establish that 18th century Bengal was a relatively integrated economy; one reliant on a system of waterways for transportation, and a network of markets spanning the province that ensured efficient trade. Referring back to Figure 2.1 (Section 2.2), Studer (2008) used a lack of co-movements in the price of grain to demonstrate a lack of inter-provincial market integration. Conversely, in the market for common rice in Bengal pre-famine, we see co-movements in prices for Calcutta, Chinsurah, a rural locale, and the Bengali average; suggesting a large degree of market integration (Figure 3.1). However, as we noted throughout Section 2, not only were there price shocks in the markets for certain commodities a year earlier for Chinsurahh during the famine event, when compared to the Bengal average, but the degree of price shock was of a far greater magnitude. Thus in this section we may determine whether or not there was a breakdown in the relationship between markets throughout the famine event, and who precisely was affected by this. We know that the effects of famine were felt across the post-partition Indian states of Bihar and West Bengal, and that it also extended into Orissa, Jharkhand and modern Bangladesh. According to Marshall (1987), it was generally the core areas of central and western Bengal who were worst affected, and Bose (1993) further elaborates on this; identifying Midnapur, Nadia, Burdan, Rajshahi, Birbhum and Murshidabad in western and central Bengal, and Tirhut, Champaran and Bettiah in Bihar as those locales which saw the highest mortality rates. Looking at Figure 3.2, we can perhaps begin to understand why the famine affected different regions to a greater or lesser degree.

Figure 3.1: Common Rice Prices Intra-Bengal 1745 – 1765

Source: Global Prices and Incomes History Group, “India prices and wages 1595-1930”, Allen and Studer

3.2 Data

Although each region had its own capital city, within Bengal the seat of power for the Nawab and the administered regions under the ex-ante Mughal Empire was at Murshidibad, in the north-east; whereas Company headquarters were in the south-east, in Calcutta. For the state of Bihar, one of the worst affected regions, the administrative headquarters was the city of Patna.

Table 3.1: Prices of Common Rice Intra-Bengal Prior to and During the Famine Event

| Year | Place | Nearest Capital | Price in Capital | Local Price | Differential |

| rupees per maund | |||||

| 1769 | Midnapur | Calcutta | 1 | 1.57 | 0.57 |

| 1769 | Chinsurah | Calcutta | 1 | 3.64 | 2.64 |

| 1769 | Tamluk | Calcutta | 1 | 1.14 | 0.14 |

| 1770 | Purnea | Patna | 4 | 125 | 121 |

| 1770 | Chinsurah | Calcutta | 0.77 | 12.31 | 11.54 |

| 1770 | Birbhum | Murshidibad | 2.66 | 13.33 | 10.67 |

| 1770 | Tamluk | Calcutta | 0.77 | 3.64 | 2.87 |

| 1770 | Rangpur | Murshidibad | 2.66 | 3.07 | 0.41 |

| *1769 | Murshidibad | Calcutta | 1 | 2.22 | 1.22 |

| *1770 | Murshidibad | Calcutta | 0.77 | 2.66 | 1.89 |

| *1770 | Patna | Calcutta | 0.77 | 4 | 3.23 |

| Midnapur from Bayly, (1816), pp. 516, Ranpur from WBSA, Letter Copy Book of the Resident at the Darbar, vol.1, 7 August 1770; Murshidibad from P.C.C.R.M, vol.2, p. 118, 24 Dec., 1770 – from Becher, Resident at the Darbar of Murshidibad, 24 Dec., 1770, in the Naib Dewans representation regarding the increase in expense of the charity of rice (P.C.C.R.M, Vol. 3, 3 Jan., 1771, p. 8); Birbhum from Hunter, Annals, pp. 422; Chinsurah from Herklots, G. (1829), Gleanings pp. 368-369, and Allen and Studer “India prices and wages 1595-1930”; Tamluk from Midnapur Collectorate Salt Records dated 15 April 1778, found via “Changing Profile of the Frontier of Bengal, 1751 – 1833”, Binod Das, (1984); Patna and Purnea from Extracts, Public Consultations, (1769), and Proceedings (1770). All prices converted from seers/rupee to rupees/maund, using weight translation of 1 seer = 1/40th maund, outlined in Hunter, Annals. | |||||

Table 3.1 demonstrates that not only was there a price differential between the outlying rural districts and the nearest respective seat of power during the famine event, but for the north-east as a whole, there was price premium compared to Calcutta (regional capital comparisons denoted with *). Murshidibad common rice prices were 1.22 rupees higher than Calcutta in ’69, and 1.89 in 1770 (the height of the famine event in the north). In Purnea, the epicentre of the famine, it was reported by the supervisor of the region, Ducarel, that rice prices had increased by 500% by 1770. What is immediately apparent is that the famine had the greatest impact in those regions that were geographically remote, and that with an increase in distance from the region’s capital, there was an increased magnitude of famine impact. This distance effect is evident even within the price data for the districts of lower Bengal, with Chinsurah, upriver from Calcutta, seeing a price shock of a far greater magnitude. We can thus use the sample of price pairs between the capital of the region and other locales within Bengal, in order to capture this distance effect on the degree of price-disparity.

Table 3.2: Regression results showing the effect of distance on market integration accross the famine event

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Variables | Pre and During Famine OLS | Pre and During Famine LSDV | Pre and During Famine LSDV without Capitals | LSDV Restricted Model (1769) | LSDV Restricted Model (1770) |

| lnDistance | 0.183 | 0.183 | 0.462 | -1.150 | 0.126 |

| (0.648) | (0.648) | (1.431) | (1.669) | (1.662) | |

| Constant | 0.0715 | 0.0715 | -0.996 | 4.188 | 1.380 |

| (2.985) | (2.985) | (5.917) | (7.212) | (6.618) | |

| Observations | 11 | 11 | 8 | 3 | 5 |

| R-squared | 0.007 | 0.007 | 0.024 | 0.192 | 0.002 |

3.3 Analysis

We can see from the results in Table 3.2 that the effect of the distance co-efficient prior to the famine was negative; an increase in distance from the respective capital was associated with a lower grain price. This changed during the famine, however, and areas further from Calcutta were more likely to see severe price increases during the famine event, indicating a reduction in market integration.We cannot conclusively provide a monocausal explanation for the observed isolated pockets of inflation, however, there are several themes explored within the literature when attempting to explain disparity in intra-regional famine-mortality rates, and these may offer some insight. Commonly cited proximate causes include barriers to trade, as EIC officials banned inter-provincial trade within the region in 1770, in an attempt to halt the spread of price shocks, and geographical differences between the rice-crop-reliant western and central parts of Bengal, and those on the eastern seaboard.

An alternative explanation, however, and one which may help explain the fact we see a similar intra-regional disparity in mortality rates (see Table 3.3), is that market integration within Bengal, as discussed in Section 3.1, was based on a comprehensive and ever-changing system of rivers, streams and tributaries. Given the increased elevation the further one moves inland, this means that the primary mode of transportation within Bengal was both directional, and reliant on the monsoon rainfall (Bhattacharya, 1983). The seasonal nature of Bengal’s transportation system meant that whilst in the eastern part of the province, i.e. Chittagong, the main rivers were open to transportation via boat throughout the year, in the western region, the streams and rivers became almost unnavigable during the usual dry months of February and June. However, during the monsoon season transportation via river was both a cheap and effective system for moving large quantities of grain across the province, and, recalling from Section 2.2 that the monsoon rains were predictably reliable in Bengal, there may once again have been an issue of entrenchment and path dependency; given there were little to no alternative modes of transportation such as a road system. Thus not only were the population of Bengal vulnerable to a change in climate, wherein any rain failure would quickly result in an agricultural shortfall of their primary crop (commonrice), but the infrastructure supporting trade between the provinces was also vulnerable to climate shocks. The Bengal Board of Revenue report, Oct. 1794, offers further support, describing two primary trade routes across the region that link the Hooghly district, upstream from Calcutta, with Eastern Bengal through the Sundarbans; stating that “during the season when the western branch of the Ganges is almost dried up, the whole trade of Bengal (the western provinces excepted)’ passed through them.” Hence in terms of geographical barriers to trade, whilst the farmers of the east had easy access to the eastern frontier of the western and central provinces during the dry months, and could therefore trade with the urban markets centred around Calcutta, particularly the farthest remits of the western and central provinces were not so fortunate. This would have been exacerbated in the years 1769/1770, where little to no rain fell even during the ‘rainy’ season; and so the movement of any ‘relief’ grain to the west would have been very much restricted by the ability to transport the necessary quantities over such a large distance with a limited infrastructure. Accordingly, for those western and central upland provinces most affected by drought, not only did lower crop yields mean a reduced grain supply, but there was also the potential for a restriction in supply via trade due to geographical constraints. Further evidence corroborates this, such as the 1775 contemporary reports by G. Vanisttart and P. Dacres; who both noted that the low lying delta areas – which existed mainly in the eastern part of the region, though to an extent, also in the west – suffered rather less. Given the disparate spatial and temporal effects noted thus far, wherein Calcutta and those provinces further east were affected much later than the peripheral provinces, and on a much smaller scale, it may be appropriate to label the Bengal famine of 1770 primarily a rural phenomenon; as urban centres such as Calcutta were largely insulated from the supply shock and subsequent price shock. However, whilst we have thus far demonstrated that the initial FAD had a greater impact on those rural populations to the west, both in terms of price shock and a lower relative supply, we must also distinguish between inter-group distributional issues within the populace; as the groups to which the famine affected chiefly belonged may have differed within the different regions.

Bose (1993) describes how rice surpluses from the relatively unaffected eastern wetlands of Chittagong and Bakarganj were sent via riverboat to provision Calcutta, and how Dacca also escaped from the worst of the crisis; though its artisan class suffered a high mortality rate. This is important, as it suggests entitlement failure occurred for the rural artisan class, perhaps due to their relative wages declining in the face of rising prices, from which they could not profit in the same way as grain producers and merchants could. In terms of the western and central provinces, according to contemporary accounts such as the memoir written by Sir George Campbell, published in Geddes (1874), those most severely affected were “the workmen, manufactures and people employed in the river (boatmen]”; that is, not the agrarian labourers working the land, rather, those employed in other sectors who “were without the same means of laying by stores of grain as the husbandmen”. A clear of example of the impact on the western manufacturing sector is the recorded mortality rate for Birbhum lime workers; whose numbers were reduced from 150 down to 5 following the famine (Hunter, 1868). Furthermore, even those amongst those of the upper classes in the west, it appears the famine took its toll; with Hunter reporting that the calamity was quite impartial between rich and poor in the region, citing the ruination of the old, aristocratic families of Lower Bengal – which were reduced to a third of their previous number. He describes in detail the case of the Rajah of Burdwan; who, despite his vast wealth pre-famine, died in such abject poverty as a victim of the famine, that his son later had to beg a loan from the colonial government in order to repay debt incurred from the Rajah’s funeral expenses (ibid.) Even in the north-east Campbell (Geddes ed., 1874.) observed that within the city of Murshidabad, the seat of power for the Nawab, it was artisans particularly in the silk industry who principally suffered; noting that a third of those who raised silk worms in the then-famous silk producing area around the city perished. The observed high mortality rate of artisans, even within the otherwise relatively lesser-affected north-eastern regions, was not an isolated event; and of those who died in Dacca, which largely escaped the ravages of famine, a large proportion were weavers and spinners according to a 1773 report, from the Controlling Committee of Commerce. Thus, contrary to what may be an intuitive assumption, that those who suffer most during dearth are those peasants working the land who own the failed crops, the highest recorded death tolls were actually amongst the rural artisans, and the urban poor. Although, this takes no account of internal migration, and migration outside of Bengal to Maratha lands; with Midnapur District Records (Firminger ed., 1926) demonstrating an exodus of peasants, primarily tribal land workers, to the Maratha-controlled districts further west.

What is particularly significant is that, not only was it those districts furthest from Calcutta, and therefore inland, which saw the greatest effects in terms of price shocks, but it was those same districts in western and central Bengal who also saw the greatest loss of life during the famine event (see Table 3.3). Furthermore, within the eastern parts of the province, those worst affected groups appeared to be those without direct access to food, such as those working on the land.

Table 3.3: Estimates of Villages Pre and Post Famine in Different Districts of Bengal

| District | Description | Change (%) |

| Birbhum | Campbell describes a reduction in the number of villages from 6000 (1765) to 4500 (1771) | -25% |

| Bhagalpur | The Supervisor’s report in April 1770 described the deaths of a third of inhabitants. | -33.33% |

| Purnea | The Supervisor’s report in May 1770 described the deaths of a third of inhabitants | -33.33% |

Birbhum: Campbell (ed.) “Extracts”, pp. 79.

Bhagalpur: Nani Gopal Chaudhuri, “Cartier: Governor of Bengal”, pp. 40

Purnea: Letter to Court, 9th May 1770, Fort William-ICH, vol. VI, 1770-1772, pp. 203

Thus there was pronounced growth in rural destitution; and a more comprehensive temporal-spatial risk model might have allowed the identification of those vulnerable areas at particularly high-risk of famine occurrence. Unfortunately, given the scanty data, the best we can do is identify that there did exist population and price shocks of a greater magnitude in the western regions, and that those affected in the east tended to be of particular labour classes. In the next section we may begin to investigate whether, aside from a geographical explanation, this distance effect may be understood in terms of shifting exchange entitlements.

Section 4: Entitlements

As seen in Sections 2 and 3, it may be appropriate to label the Bengal famine of 1770 primarily a rural phenomenon of the central and western provinces; wherein urban centres, such as Calcutta, were largely insulated from the supply shock and subsequent price shocks. Furthermore, those who were affected in the east tended to be artisans and the urban poor, often rural migrants. In this section we must therefore establish whether or not these affected groups suffered from substantial entitlement declines, and if so, what the characteristics of these entitlement failures were. That is, as Sen hypothesised in regards to the 1943 Bengal famine (1981, pp. 63), is this growth in rural destitution understandable in terms of shifting exchange entitlements?

4.1 Method

In terms of the Great Bengal Famine of 1770, there have been numerous claims levied by Sen and others as to the precise forms any entitlement failures took; though there are four key themes present in most bodies of work on the famine which may be identified as existing within the remit of entitlement debates, rather than issues of FAD. Sen’s own conclusions about the proximate causes were that British interference caused a direct entitlement failure, in the form of reduced endowments due to an increased tax-burden (Imperial Illusions, 2007). This meant that relative wages were too low during a period in which food availability decline occurred, such that prices were driven too high for people to successfully command food. That is, there was both a direct entitlement failure, and an unfavourable shift in the exchange entitlement mapping; one which would have seen low-income individuals unable to exchange their paltry wages for food. Others, such as Chaudhury (1995), claim that the proximate cause of the famine was the destruction of food crops on the part of the EIC; in order to clear the land for the cultivation of opium poppies and cotton. Chaudhury and contemporaries have used the 1770 famine to illustrate the so-called ills of the concentration of land resources for the production of ‘cash crops’ intended for export, without first establishing preventative measures against famine vulnerability. Similarly, Damodaran (2007) also cites a loss of land intended for food output in the wake of EIC commercialisation; though in this instance he is referring to “the gradual erosion of traditional systems of subsistence and its ecological basis, access to common lands, trees etc.” As such, they claim that the famine did not occur because of food ability decline due to crop failure alone; rather, the population was made more vulnerable to a climate shock via a reduced agricultural production capacity, and thus FAD decline was exacerbated via endowment loss and production failure. Another key entitlement failure argument levied against EIC presence in Bengal is tangentially tied to the aforementioned issue, though specifically refers to trade entitlement failures; that is, the EIC’s exportation of strategic resources in the form of raw materials using tax revenue to fund the purchases. This came with an accusation of resource stripping for profit. There is a sizeable literature on the topic of unilateral trade flows out of India, wherein the previously export intensive region of Bengal had high import taxes enforced by the British for Bengali finished goods. Indeed, even contemporary commentators such as Adam Smith compared the export of strategic raw materials to Britain as “plunder”, referring to the Court of Proprietors as the Court for “the appointment of plunderers of India” (1776, pp.812). The fourth key theme, however, is one that exists intersectionally with the issue of geographical constraints proposed in Section 3; that is, the break-down in the market for rice, as EIC officials banned the intra-provincial trade of the commodity between the districts in 1770. This ban on the trade of rice between the districts was an attempt to both halt the spread of price shocks, and to prevent exploitation by grain merchants; who at the beginning of the famine event were purchasing rice from the lesser affected districts, and selling it elsewhere at inflated prices for profit. Much like the geographical explanation in Section 3, a ban on the movement of the grain supply to areas in which it was demanded represents a breakdown in the market mechanism, however, unlike a geographical constraint, when an artificial barrier to trade is enforced it also represents a break down in trade entitlements. In order to establish whether or not famine-affected groups suffered from substantial entitlement declines, and if so, what the characteristics of these entitlement failures were, we may thus construct a four-fold analysis. Using both contemporary qualitative sources and quantitative data we can estimate the relative importance of the following; increased land taxation, the decreased production capacity from a turning over of land to cash-cropping, the EIC’s exportation of strategic resources, and the effects of trade restrictions between districts.

4.2 Data

4.2.1 Land Revenue Tax and Direct Entitlement Failure

A commonly cited cause of decreased ability to purchase food through legal means, particularly for the peasants working the land, is taxes levied by the EIC throughout the famine period; and the increase of these taxes in 1771 to combat revenue shortfall from a reduced tax base. Throughout the famine event there were few tax-remissions paid, in 1770 there was only a 5 per cent remission granted on those taxes paid for the agrarian year ‘69/70, and in 1771 taxes were increased by a further 10% to compensate for this. Chaudhuri, in Cartier, wrote that “the Bengal government was more concerned about the collection of revenue than about the famine stricken people is evident from the fact that more revenue was collected in 1770–71, the year of the famine, than in 1769–70, the year of dearth which resulted in famine” (pp. 31). It is a sentiment shared by many of his contemporaries, including Sen, and one which echoes those writing during the colonial period, such as Hunter in Annals. Hunter illustrates the sequence of events that lead to the tax increase, noting that Cartier in January of 1770 expressed his concerns to the board about the necessity of a land tax remission, but then rescinded that advice only ten days later; given the council had not yet found any ‘failure in the revenue or stated payments’ (pp. 20). Instead, during the height of the famine in April of 1770, the board acted on the advice of the Muslim Minister of Finance Reza Khan, and added 10% onto the land tax of the following year. However, when reviewing the actual taxation revenue figures, we notice several things; firstly, for the agrarian calendar year ‘69/’70 land revenue collected was 14.74 million rupees, and in ‘70/’71, 13.82 million rupees. Furthermore, for those districts affected most by the famine in the western region of Bengal, revenue collections were actually 34.72 percent higher in ‘70/’71 than in ‘69/’70 according to the Factory Records at Murshidabad (IOR, 1771). What should be immediately apparent is that the ‘tax’ increase was not ad valorem. The land rental rate, or tribute, for that is what academics mean when they refer to land taxes, was a fixed sum by acreage of tillable land which on average was 10% higher than the previous year. Thus what is not often considered when discussing so called ‘tax increases’ – for the confusion stems from academics mislabelling land rental tributes, which in Company eyes were something very different to taxes (which were levied only on trade) – is that these revenue figures occurred within the context of those issues discussed in Section 2. That is, there was significant inflation, and Section 3; said inflation was of a greater magnitude in the more isolated rural regions to the west. Hence, those regions in which a significant amount of inflation occurred, relative to the less volatile price increases in Calcutta, were the very same rural locales which bore the burden of an increased land tribute. Even using the relatively smaller inflationary price effects in Calcutta, we can thus demonstrate the effect of inflation on reported land revenue figures, by constructing a relative price index to deflate the reported government revenue figures from Bengal (Table 4.1)[1]. (Wherein government revenue figures refer to the money collected by the ruling authority through diwani rights, which until 1763 were the right of the Mughal Emperor, but were appropriated by the EIC from 1766 onwards.) The price of common rice is used as a proxy for a comprehensive price index, as in this instance we are specifically referring to the impact of an increased land tribute, and common rice was, as discussed in Section 2, the primary crop produced in both western and eastern Bengal.

Table 4.1: Prices in Bengal, 1751-1871

| Year | Price of (Common) Rice (Rs. per maund) | Bengal Government Revenue (Current Prices) | Bengal Government Revenue (1801 Prices) |

| 1751 | 1.18 | ||

| 1755 | 1.24 | 16.62 | 13.40 |

| 1761 | 0.95 | ||

| 1763 | 1.29 | 20.47 | 15.87 |

| 1768 | 0.89 | ||

| 1769 | 1 | ||

| 1770 | 0.77 | ||

| 1771 | 3.33 | 22.57 | 6.78 |

| 1772 | 1.43 | ||

| 1773 | 1.33 | ||

| 1781 | 1.14 | 25.57 | 22.43 |

| 1791 | 1.18 | 25.93 | 21.97 |

| 1793 | 1.67 | 26.8 | 16.05 |

| 1801 | 1 | 26.8 | 26.80 |

Notes: Rice prices are the Bengal average for 1751 and 1755, post 1755 Calcutta rice prices are used. Current value Bengal Government Revenue figures are from Datta (2000) pp. 333-334.

What is immediately apparent when viewing Table 4.1, is that the reported land revenue figures are somewhat misleading when viewed by themselves, without taking into account the effect of inflation on prices. By using common rice prices to deflate Bengal government revenue to constant prices, we see that, rather than the oft quoted increase in government revenue for the year 1771, in real terms, the EIC actually collected a 57% decrease in revenue for the year 1771 when compared to 1763. This is not to suggest that the EIC should have increased the tributes to combat inflation, nor does it imply that the impact of taxation on an already struggling populace did not result in a further loss of life. Rather, it suggests that the use of these figures in the historiography of the famine, without accounting for inflation in the affected regions, is misleading. Whilst certainly a burdensome tax regime may in and of itself reduce the endowment of an already vulnerable population, it is unlikely that the increase in tributes for those agrarian land holders in 1771 vastly affected the exchange entitlements during the height of the famine event in ‘69/’70.

4.2.2 Land Re-consignment and Endowment Loss

The second of the four main themes underlying the criticisms of EIC actions in Bengal, is the accusation that one of the foremost proximate causes of the 1770 famine, and others that followed, was cash-cropping. Chaudhury (1995) claimed this caused direct entitlement failure in the form of a reduced endowment, and thus a reduced production capacity. However, we know from contemporary records that Bengal had certainly not reached full production capacity prior to 1770; even in the easternmost district of Chittagong, which largely escaped the impact of the famine, according to both Midnapur District Records (Firminger ed., 1926, pp. 53), and corroborated by Serajuddin (1971, ch. 5), by 1761 only 25% of the district was cultivated. Later in the century, a rising demand for food would see cultivation extended in the east, and in 1784, according a Bengal Revenue Consultations report (1784), Jessore was estimated to possess 200,000 acres of cultivatable land which was then reclaimed from the marshes and settled over the following century (Westland, 1871, pp. 135). Furthermore, little consideration has been paid by Chaudhury (1995), and contemporaries, to the nature of cultivation in Bengal. That is, precisely what types of crops were grown, and how they were grown. It is quite one thing to suggest that a field of wheat may be cleared and opium poppies grown in its place, but another thing entirely when we consider that rice was the primary crop upon which Bengals agricultural output rested; and rice particularly enjoys conditions in which it is three to six feet underwater. Thus to suggest that an increase in the cultivation or poppies, cotton etc. reduced the productive capacity of food grain is a little bit of a non-sequitur, given the two types of crop do not compete for land.

4.2.3 Exportation, Resource Stripping and Exchange Entitlement Failure

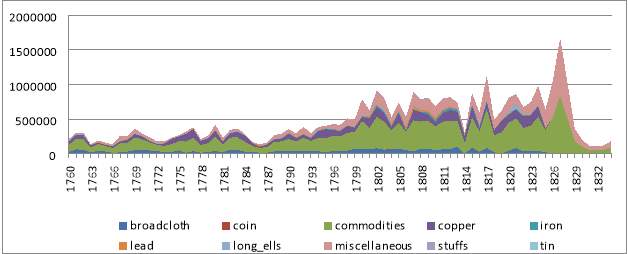

What we must first establish before any ensuing discussion, is that prior to the arrival of the EIC to Bengal, the region had been an export intensive province; with particularly the northern and eastern parts of the province producing a large number of finished goods, which were then shipped to other regions in Asia and the Middle East. India as a whole ran a current account surplus with the rest of the world. However, the arrival of the EIC meant several things for Bengal’s economy in terms of international trade; when the British received taxation rights for the province in 1766, and here we are referring to both taxes on trade and land revenue tributes, the EIC was thus able to use this revenue for the purchase of goods intended for export. This is significant, because it meant that there was no need to ship bullion to India to finance the purchase of these goods. Furthermore, given that the EIC had established a duty free stronghold in Bengal, such that there were no taxes or duties to paid for finished British goods exported to the province, nor were there any taxes to be paid on resources or raw materials purchased in the region to be sent home to Britain, this lead to a one way flow of resources out of Bengal. This unilateral trade flow was exacerbated by the fact that British markets at home did have taxes in place against those finished goods that Bengal historically exported; such as cloth, jute, refined Indian sugar etc. Thus there was little demand for Indian finished goods, only the resources that could be purchased by the EIC using locally financed revenue sources. It was this scenario that led Adam Smith and others to label it a situation of unilateral trade in which only Britain benefitted; given they paid the non-tax price for raw materials using revenue sourced from within Bengal, and were then able to sell British-produced finished goods back to the region with no duties imposed. Using data from Bowen (2007), a database of compiled statistics relating to bilateral trade between Britain and India between 1755 and 1834, we can thus create projections to demonstrate the flows of trade prior to and during the famine event.

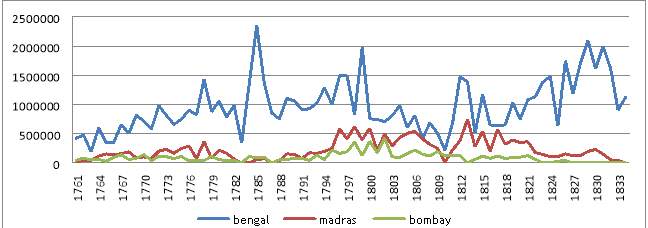

Figure 4.1: Aggregate imports by port of origin, 1761-1834

Figure 4.1 illustrates aggregate imports to Britain by the EIC by port of origin, over the period 1761 to 1834. What is immediately apparent, is that trade with Bengal was quite volatile over the entire period of the EIC’s operations, however, we also see that during the famine event ’69 – ’73, not only was there a spike in the volume of imports arriving in Britain from Bengal by way of the EIC, but we also see corresponding decreases in the volume of goods imported from Madras and Bombay. One possible explanation for this could have been an increase in overall trade with Bengal during the period; however, and if we look at the export figures (Figure 4.2), we see that for the same period in which a dramatic increase in imports from Bengal occurred, there was a similar increase in British exports, at least at the start of the famine event, though this then declined by 1773. Thus the trade data may suggest several things. Firstly, an increase in imports from Bengal, with co-movements in the other direction for Madras and Bombay are perhaps unexpected; given that they imply priority in shipping leaving Bengal during the famine event. Conversely, given there were also movements in the opposite direction in terms of imports to Bengal from Britain, and this was primarily in the form of commodities, this may suggest some sort of famine relief. The trade flow data may superficially support this idea of extraction at the cost of lives; considering that, for the same period in which there was a dramatic increase in imports from Bengal, there was a remarkably smaller increase in British exports to the province. However, I find this to be a rather simplistic explanation; firstly, the famine was primarily a rural phenomenon, and, as discussed in Sections 2 and 3, began to affect districts in the north a year prior to the regions in the south east and the port of Calcutta.

Figure 4.2: Imports from Britain to Bengal by way of the EIC, 1760-1834, disaggregated by commodity

Note: Silver bullion imported from the 1980’s onwards has been excluded, as it distorted the scale

4.2.4 Trade Restrictions and Trade Entitlement Failure