HYPOTHERMIA

Introduction

Hypothermia is defined as a core body temperature of less than 35 0 C.

It may be missed in patients who present for other reasons, unless it is specifically looked for.

A range of generally accepted drug and other treatment modalities used to manage normothermic patients will often be problematic in the hypothermic patient and may require modification.

Physiology

In warm blooded animals, the hypothalamus stimulates a compensatory response to cold exposure by activating:

Shivering can increase metabolic rate up to 5 times, producing increased endogenous heat, but ceases once glycogen stores are depleted or the body temperature falls below 30 ° C.

Pathophysiology

As the body core temperature lowers from the normal range there is progressive organ dysfunction and eventual death.

The level at which this occurs varies between individuals.

Classification of Hypothermia

Hypothermia is defined as a core body temperature of less than 35 0 C.

It is classified into three groups:

Mild: A core temperature of 32 0 C – 35 0 C.

The body copes with various thermogenesis compensating mechanisms including shivering. There may be some mild slowing of all physiological functions.

Moderate: A core temperature of 29 0 C – 32 0 C.

Here there is a progressive failure of thermogenesis compensating mechanisms.

Severe: A core temperature of less than 29 0 C.

Compensatory mechanisms fail and the body temperature approaches that of the surrounding environment, (poikilothermia).

Causes

Nutritional:

Starvation / malnutrition

Hypo-endocrine states:

3.Thermoregulatory center dysfunction:

Cold Diuresis:

Exposure to cold stimulates peripheral vasoconstriction to conserve heat.

Shunting of circulation centrally produces an elevation of blood pressure which in turn inhibits antidiuretic hormone (ADH or vasopressin), increasing urine volume. A “cold diuresis” results with consequent dehydration.

Clinical Features

Although hypothermia is most common in colder climates with environmental exposure, severe accidental hypothermia can also be seen in the metropolitan regions, with infants, the elderly and the socially isolated being at highest risk.

A common hypothermia scenario in the metropolitan regions is the elderly person found confused on the floor in winter. Considerations here must also be given to the possibility of stroke, trauma (especially hip fractures) and intracerebral bleeds and to the possibility of rhabdomyolysis.

The following is a guide. In practice there can be wide individual variation, which may in part be related to previous acclimatization.

Mild Hypothermia:

Compensatory mechanisms are active:

Moderate Hypothermia:

Continuing CVS depression, with the development of arrhythmias, including:

Severe Hypothermia:

In severe hypothermia there is complete failure of thermoregulation.

The body adopts the temperature of the surrounding environment (poikilothermia) and loses the ability to rewarm spontaneously.

Signs of life may become almost undetectable.

1.Severely depressed neurological function, including:

2.Respiratory depression, apnea.

3.Myocardial effects:

Profound depression of myocardial function, with bradycardia, hypotension and life threatening arrhythmias, VF (especially at 22 0 C) and asystole, (especially at 18 0 C)

In a field setting, where measuring core temperature is not possible, “moderate” and “severe” may be grouped together (as “profound”) in distinction to a “mild” hypothermia, as they typically share the readily assessed clinical features of absence of shivering and an altered mental state.

Further Complications:

1.Reduced drug metabolism:

The pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of many drugs,including adrenaline and insulin, are substantially altered or unknown at low body temperatures.

2.Resistance to electrical defibrillation or cardioversion.

3.The myocardium becomes “irritable” and rough handling of the patient may result in arrhythmias including VF.

Less commonly, the following have also been reported, however the direct causal relationship with hypothermia is less certain:

4.Renal failure

5.Rhabdomyolysis

6.Coagulopathy (DIC)

7.Pancreatitis.

Factors which may identify the Non Salvageable Patient: 1

The following factors have been put forward, although their clinical utility is questionable.

A serum potassium greater than 10 mmol / L

A core temperature less than 6 0 Celsius.

A core temperature less than 15, 0 Celsius if there has been no circulation for > 2 hours.

A venous pH of < 6.5

Severe coagulopathy

Intracardiac clots on thoracotomy.

Failure to obtain venous return on ECMO.

Investigations

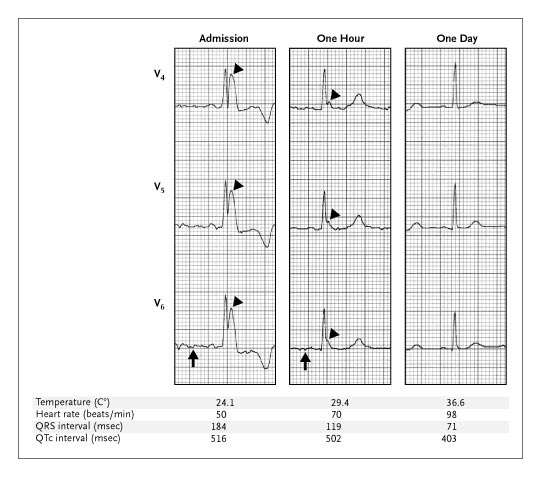

ECG

ECG changes include:

Development of the J or “Osborne” wave:

Serial hypothermic ECG changes showing J waves. 3

This is an extra upward deflection between the R and the T wave. It is often fused with the downstroke of the QRS complex, (see above).

Its rounded convex upward contour helps distinguish it from an RSR pattern. Together with the spike of the QRS, may form a typical “spike and dome” appearance.

It may be confused for a T wave with a short QT interval, however the later actual T wave will still be seen. This T wave may be inverted.

It is best seen on V3 and V4.

J waves, although seen in hypothermia, are non-prognostic, and non- specific.

Non specific T wave changes

Prolongation of all phases of the cardiac action potential, including the QT interval with a subsequent risk of Torsade

Arrhythmias:

Muscle shivering artifact in mild cases.

Blood tests:

1.FBE:

Hematocrit may be increased due to hemoconcentration (secondary to the cold diuresis).

2.U&Es and glucose:

Hyper or hypoglycemia may occur. Muscle glycogen is the substrate preferentially used to generate heat by shivering and so all hypothermic patients will need glucose.

Additionally, insulin is less active at temperatures less than 30 0 C and this may result in mild degrees of hyperglycemia.

3.Coagulation profile

4.LFTs

5.Lipase

6.CK/ myoglobin

7.ABGs:

Note that it is currently recommended that the ABG results should be interpreted at face value, rather than attempting to adjust them according to the patient’s temperature. 2

Other investigations are not routinely required in hypothermia. They should be done as clinically indicated.

CT Scan Brain:

Patients with profound hypothermia will usually have an altered conscious state.

The threshold for CT scan of the brain should be low, especially if the patient does not improve with rewarming.

If the patient does not respond within a reasonable time frame, secondary pathology or indeed the causative pathology should be sought with a CT scan of the brain.

Management

Initial General Measures:

1.Immediate attention to any ABC issues.

2.IV fluids:

Volume will generally be needed (due to cold diuresis).

hese should be warmed.

Sodium chloride 0.9% solution warmed to approximately 40 to 42 °C is the preferred fluid choice, and should be administered cautiously as the patient rewarms and their intravascular space expands.

A relative level of hypotension can be normal in hypothermia – it is important to be aware of this and to regularly reassess fluid requirements as the patient rewarms to avoid intravascular fluid overload.

3.Electrolyte and glucose disturbances:

Correct hypoglycemia, mild hyperglycemia requires no special treatment.

Glucose is required as an energy substrate in all hypothermic patients. If glucose cannot be taken orally, then some should be administered intravenously. 5

See latest Therapeutics Guidelines for suggested regimes of glucose administration.

Electrolyte concentrations may change rapidly and unpredictably with rewarming, and should be monitored closely. Any electrolyte disturbances should be corrected.

4.Gentle handling of patient:

Rough handling especially in the profoundly hypothermic may precipitate arrhythmias

5.Establish monitoring:

Continuous ECG.

Pulse oximeter.

Core temperature monitoring:

Body core temperature may be measured at a number of sites, including esophageal, tympanic, bladder and rectal.

Standard thermometers are often unreliable below 34 °C.

Infrared tympanic thermometers are unreliable in a field setting, however they do seem to correlate well with core temperature in hospitalized patients, (possibly because most hypothermic ED patients have cooled relatively slowly allowing temperatures to equilibrate throughout the body).

An oesophageal probe is the most reliable method, but typically this is only possible in a ventilated patient.

Ongoing core temperature monitoring urinary catheter devices such as the Curity 12 French Foley urinary catheter with temperature probe, is often the most practical device as it is most easily placed.

End tidal CO2 monitoring in intubated patients. Recordings will read lower than at normal temperatures and are therefore more difficult to interpret.

CVCs:

Note that central lines should be avoided in the profoundly hypothermic patient (due to the risk of precipitation of arrhythmias) A short femoral line is a good alternative if central access is required.

6.Look for and treat as necessary any coexistent trauma / pathology.

7.Arrhythmias:

Benign arrhythmias, such as sinus bradycardia, slow AF, other atrial arrhythmias and transient ventricular arrhythmias are common physiological responses in hypothermia and require no specific treatment other than rewarming.

Most cardiac arrhythmias associated with hypothermia will resolve spontaneously with rewarming.

Antiarrhythmic drugs are not generally indicated unless malignant arrhythmias are present. Although there is limited evidence to support any specific drug, magnesium seems to hold some promise to treat ventricular arrhythmias associated with hypothermia. 5

Rewarming:

Rewarming is the definitive treatment.

The techniques used will depend on the patient’s core temperature, clinical status and the available resources.

Rewarming in Mild Hypothermia

Simple passive techniques are usually all that is required in these cases, providing the patient has retained the physiological capacity to shiver and to generate body heat.

They include the following:

1.Protection from the environment and especially from any wind (to reduce evaporative and convective losses)

2.Removal of any wet clothing, (water has 25 times the thermal conductivity of air)

3.Drying the patient.

4.Provision of an insulation blanket, (shiny side in).

This will reduce radiative, evaporative and convective losses.

5.Warm drinks, if able to be tolerated are helpful.

Rewarming in Moderate Hypothermia

Here the patient’s thermoregulatory mechanisms begin to fail and so in addition to the above passive techniques for rewarming more active measures must also be taken to assist the patient in achieving a core temperature of at least 32 0 C.

Active external measures include:

1.Radiant heat sources.

This may include immersion in warm water in some circumstances (for patients who will not require any other medical interventions) or close body to body contact when in the field.

2.Forced Air-Blanket devices. The device is usually set at 43 0 C.

3.Warm bathwater immersion is discouraged in these patients, as this impairs the overall ability to properly manage and monitor the hypothermic patient.

Active internal measures include:

1.Warmed and humidified inhaled oxygen therapy.

This can be done via specific delivery devices.

Humidification of the inspired oxygen is important to help reduce evaporative losses from the respiratory tract and because dry air has relatively low thermal conductivity as compared to humidified air.

The heating coil on the device should be set at 40-42 0 C.

2.Warmed IV fluid therapy.

A specialized heating device is best. The heating coil in the warming device is generally set between 40-42 0 C.

Alternatively fluid bags stored in a blanket warmer may be used.

Note that IV administered fluids should never be microwaved.

Possible theoretical problems with the two external techniques (radiant heat and forced air blanket) have been said to include “the afterdrop” phenomenon and “rewarming shock and acidosis”. These concerns however have little, indeed probably no, clinical relevance.

Rewarming in Severe Hypothermia

Generally severe hypothermia responds well to a combination of all the above methods used for mild and moderate hypothermia.

On occasions, if there is an inadequate response to these measures or if the patient is particularly unstable, especially with respect to the cardiovascular system, including the “arrested” patient, then more aggressive invasive active internal techniques may be necessary to rapidly achieve a core temperature of at least 30degreesCelsius, (a level below which more malignant arrhythmias may occur).

Options here include:

This is the best means of rapidly rewarming a patient (up to 7.5 0 C per hour) as well as providing a circulation and oxygenation in the arrested patient.

Cardiac Arrest in Hypothermia:

Cardiac arrest presents a particular dilemma in the severely hypothermic patient. At core temperatures of less than 29 0 C, signs of life can be extremely difficult to detect.

“Rough handling” is said to predispose to VF or other malignant arrhythmias. The dilemma has been put that if the patient appears to have no pulse, yet has a “perfusing” rhythm (a form of PEA), then should CPR be commenced with the subsequent risk of inducing a worse rhythm such as VF?

Current consensus opinion suggests that the “rough handling” issue has been overstated, particularly in relation to intubation which is now considered safe. The issue more probably more relevant in the prehospital setting where issues such as the helicopter winching of patients to the horizontal position are encountered.

If a monitored patient appears to be in cardiac arrest with no detectable pulse, despite the presence of a “perfusing” rhythm, then CPR should be commenced. The proviso to this is that a very careful effort should be made to detect the presence of a pulse first, (at least 45 seconds should be taken to do this)

An unmonitored patient in the field is another issue. If after a very careful examination for a pulse, there is none, then CPR should be commenced. The proviso to this is that further medical assistance will be possible within a reasonable time frame.

In cardiac arrest it should be further noted that the severely hypothermic patient will be resistant to both drug and electrical therapies. If there is no initial response to these then further attempts are unlikely to succeed until rewarming has occurred to at least 32 0 C.

There are well-documented cases of complete recovery from very prolonged hypothermic cardiac arrest, and prolonged resuscitative attempts are warranted in the hypothermic patient.

Disposition

The presence of concomitant trauma or illness will influence disposition for any given case.

Mildly hypothermic patients can be managed as outpatients after a period of emergency department care.

Patients with moderate or severe hypothermia will need admission, and may need admission to an intensive care unit or high dependency unit.

References:

1.Daniel F. Danzl, and Robert S. Pozos Accidental Hypothermia: NEJM Vol. 331:1756-1760 December 29, 1994

2.Rogers I, Hypothermia in “Textbook of Adult Emergency Medicine”, Cameron et al 3rd ed 2009.

3.Krantz NJ, Giant Osborne Waves in Hypothermia, NEJM vol. 352, January 13, 2005.

4.Hypothermia in “The Emergency Medicine Manual” Robert Dunn et al 4th ed 2010.

5.Wilderness and Toxicology Therapeutic Guidelines, 2nd ed 2012.

Dr J Hayes

Reviewed October 2012.

You have to be 100% sure of the quality of your product to give a money-back guarantee. This describes us perfectly. Make sure that this guarantee is totally transparent.

Read moreEach paper is composed from scratch, according to your instructions. It is then checked by our plagiarism-detection software. There is no gap where plagiarism could squeeze in.

Read moreThanks to our free revisions, there is no way for you to be unsatisfied. We will work on your paper until you are completely happy with the result.

Read moreYour email is safe, as we store it according to international data protection rules. Your bank details are secure, as we use only reliable payment systems.

Read moreBy sending us your money, you buy the service we provide. Check out our terms and conditions if you prefer business talks to be laid out in official language.

Read more