This study assessed the Socio-economic Impacts of Tropical Storm Erika on the people in St. Joseph, Coulibistrie village and their adaptation strategies

The study used both quantitative and qualitative approaches. The study had discussions with key Stakeholders/ Informants at district and village levels as well as randomly sampled households. Quantitative Household Questionnaires and Qualitative Key Informant Interviews were used to collect the data.

The study founded out that Tropical Storm Ericka affected the people’s socio-economic livelihoods and critical properties such as agriculture, health, education, housing, water and property and assets.

These are the key recommendations:

Keywords: livelihoods, Tropical Storm Ericka, Natural disaster.

This study explores the Socio-economic impacts of Tropical Storm Erika on the people in St. Joseph, Coulibistrie village and their adaptation strategies.

The main aim of this study is to provide a thorough understanding of the Socio-economic impacts of Tropical Storm Erika and the underlying causes of the community’s vulnerability. The contributions of this research should be able to help other stakeholders to undertake continued research in the issues that may arise in the study and need further attention.

Dominica officially the Commonwealth of Dominica, and more commonly known as the “Nature isle of the Caribbean” is an island country in the Lesser Antilles region of the Caribbean Sea, south-southeast of Guadeloupe and northwest of Martinique. Its area is 750 square kilometres (290 sq mi) and the highest point is Morne Diablotins, at 1,447 metres (4,747 ft) elevation. The population was 72,301 at the 2014 census. The capital is Roseau, located on the Leeward side of the island.

On August 27, 2015 a tropical storm passed over Dominica producing extraordinary rainfall with high intensity. Owing the mountainous island topography and the saturated condition of the soil, the heavy rainfall resulted in intense and rapid flooding. Dominica suffered severe infrastructural damage, primarily related to transportation, housing and agriculture with the worst damage occurring in the south and south east parts of the island.

The frequency of natural disasters has been increasing over the years, resulting in loss of life, damage to property and destruction of the environment. The number of people at risk has been growing each year and the majority are in developing countries with high poverty levels making them more vulnerable to disasters (Living with Risk 2006:6).

Grunfest (1995) debates that because of high poverty levels, people have become more and more vulnerable because they live in hazardous areas including flood plains and steep hills. They have fewer resources which makes them more susceptible to disasters. They are less likely to receive timely warnings. Furthermore, even if warnings were issued, they have fewer options for reducing losses in a timely manner. The poverty level affects the resilience and process of recovery from disasters. Disaster mitigation, preparedness and prevention needs to address socio-economic issues not only geological and meteorological aspects.

This study is important because it assesses and evaluates the effects of Tropical Storm Ericka on the village. Dominica has always been in the pathway of hurricanes and tropical storms and suffers lots of damages to the country year after year. Last year when Tropical Storm Erika hit Dominica, after it impacted Dominica an evaluation was done assessing the Rapid damage and Impact, but this was done only to create and inform the recovery strategy. The main focus was to assess the estimate in damages to physical assets and the corresponding losses, this Rapid Damage Impact Assessment is broadly based on the Damage and Loss Assessment (DALA) methodology developed by the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean. This Study will help identify the major impacts of TS Erika on the livelihoods of the villagers in Coulibistrie, as it was one of the villages that suffered greatly during this time. It will also give advice and suggestions on a broad scale as to how the villagers and the NGO’s/ government can help the people of that community

The study will also provide information on all 5 aspects of the livelihood framework. The full extent to the affected areas cannot be realized until it has been properly analyzed and researched.

This study is also of importance because it will provide information for academic purposes and also encourage further studies as it will lead the way to better understanding of the way natural disasters effect communities in developing countries such as Dominica.

It can also provide government with information that can be used in planning for rural people and to find ways of improving their Livelihoods. Open doors to greater opportunities that might available or unutilized by both the government and people. The study will provide them with information, which can help them redevelop their strategies and policies.

Community leaders and members will also be informed of how Tropical storms/ Hurricanes can impact the local livelihood for their people. Therefore, the purpose of this research will be to understand and explain the extent of the impacts of Tropical storm/ Hurricane on the local livelihood of the people.

The issue which this study addressed is Socio-economic Impacts of Tropical Storm Erika on the people in St. Joseph, Coulibistrie village and their adaptation strategies. The study area is located on the coastal region and it has a river passing right through the middle of the village and located in a valley like area. This villa was chosen because it was one of the villages categorized as a special disaster zone, a total of ten (10) villages was placed in that category because of the amount of damage that was inflicted during the disaster. The population in Coulibistrie has decreased over the years from 517 in 1991 to 465 in 2001 to 419 in 2011. A wide variety of crops, some of the other crops grown include Banana, Citrus, Cucumber, Yam, Plantain, Tomato, Potato, Coffee, Castor. Some of the farmers also rear livestock and fishing is practiced. Given its geographical location of which is along the river and the sea front, the village has a limited control of the hydrological events ensuing from the natural flow of the river.

This area has been over the years affected by heavy rain and other small environmental disturbances but none has affected the village as Tropical storm Ericka has since the passing of Hurricane David in 1979 which left a mark on the whole country.

Subsequently, a huge number of research have been carried out on the assessment plan, and recovery but little has been done to assess or evaluate the impact it has had on the livelihoods of the people.

The overall objective or purpose of this study will be to assess the Socio-economic Impacts of Tropical Storm Erika on the people in St. Joseph, Coulibistrie village and their adaptation strategies

The conceptual framework identified to aid the research is Disaster Risk Reduction. This is the systematic development and application of policies, strategies and practices to minimize vulnerabilities and disaster risks throughout a society, to avoid (prevention) or to limit (mitigation and preparedness) the adverse impacts of hazards within the broad context of sustainable development. As shown in the introduction, Natural Disasters are becoming more and more frequent and intense due to climate variability. In that case, it might not be possibly to remove the risks of tropical storms. The important fact is to understand the risk of tropical storms and the associated effects inside of the the framework of Disaster Risk Reduction. This can be done by developing the flood hazard and risk profiles which can be used to design appropriate measures to manage and mitigate the floods and build people’s adaptation capacity and resilience (Report on the Regional Stakeholders’ Consultative Workshop on Disaster Risk Management,2004).

Although there hasn’t been much studies done in the country on the frequency and intensity of disasters, according to news reports and actual observations its clear to see that over the years the impact of these disasters are growing as the years passes-by one of the main reasons for this is Global warming.

Notwithstanding the increase in the frequency and magnitude, no comprehensive impact assessment study on the socio-economic livelihoods of people has been started.

The study comprises of 5 chapters as outlined below:

This chapter shows the background and introduction to the research study. It gives a foresight as to how the research was carried out, the conceptual framework and objectives. The chapter also provides the significance and scope of the study

This chapter shows the review of past research work along with the addition of more knowledge to the research study. It also points of the weaknesses and critically analyses published bodies of knowledge by means of justification and comparison to previous studies. It thus contains review of evidence-based data.

This chapter gives an introduction, the study design, sample selection and size, study methodology, and how the data was analyzed. It as well shows the credibility, transferability and dependability of study.

This chapter gives an introduction of the discussion of results. Furthermore, the chapter presents the findings on the results, copping strategies, development options to deal with tropical storms / hurricanes / cyclones and the effects it brings, limitations, vulnerable groups, interpretation and implications of the research study. Ending with recommendations for if further research is required.

This chapter gives an introduction for the conclusion and the recommendations of the study.

The term “livelihood” has been defined in a variety of ways by various authors. Considering the most common definition, a livelihood can be defined as people’s capacity to maintain a living (Chambers and Conway, 1991). In the last few decades, several institutions (e.g. FAO, UNDP, DFID etc.) have developed frameworks to analyze sustainability of livelihoods. Most of these frame- works are similar. DFID’s (the UK Department for International Development) conceptual framework, however, draws attention to the measured changes in different factors that contribute to livelihoods: five capitals, institutional process and organizational structure, vulnerability of livelihoods, livelihood strategies, and outcomes (DFID, 1999).

“Livelihood capitals” refer to the resource base of a community and of different categories of households (FAO, 2005). They are grouped into human, natural, financial, physical, and social capitals (DFID, 1999; FAO, 2005). The capitals available constitute a stock of asset which can be stored, accumulated, exchanged, and put to work to generate a flow of income (Rakodi, 1999; Ellis, 2000; Babulo et al., 2008). Using the available five capital assets, people engage in various livelihood strategies to achieve livelihood objectives. Therefore, “livelihood strategies” are the range and combination of activities and choices that people make in order to achieve their livelihood goals (DFID, 1999; FAO, 2005). These livelihood activities are subject to the endowment of livelihood capital because they determine the possibilities for rural household to achieve goals related to revenue, safety, and welfare (Van den Berg, 2010). In other words, livelihood strategies can also be understood as the means to cope with external disturbance and maintain livelihood capabilities (Chambers and Conway, 1991; Ellis, 1998, 2000; DFID, 1999; Adato and Meinzen-Dick, 2002).

Due to spatial variations of capital assets in settlements and agro-climatic zones, the differential access to, or endowment of, livelihood assets determines the choice of a household’s livelihood strategies (Babulo et al., 2008). It means that livelihood outcomes become critical to rational use and improve efficiency of livelihood capitals at the household level subject to the goal of maximizing these outcomes (Brown et al., 2006).

The livelihood strategy has been increasingly studied over the past years in the world, and the significant progress has been made in classification of livelihood strategies, impact elements of livelihood strategies, and role of livelihood strategies in poverty alleviation.

According to the definition of a livelihood strategy, many scholars have conducted the classification study of livelihood strategies (Pichón, 1997; Browder et al., 2004; Jansen et al., 2006; Brown et al., 2006; Alemu, 2012). For example, in Alemu’s (2012) study, livelihood strategies have been classified into four categories: only farm, farm and non-farm, only non-farm, and non-labor. Different from Ansoms’ study, Soltani et al. (2012) emphasized the classification of livelihood strategies and highlighted the dynamic natures of a livelihood strategy. In the case of Zagros from Iran, they classified livelihood strategies into three types as follows: forest/livestock strategy, crop farming/livestock strategy, and non-farm strategy. Their study revealed that a number of households have shifted from a strategy based on forest and livestock to a strategy of mixed practices since the end of 1980s.

Since 1990s, livelihood analysis has become the dominant approach to understanding how rural residents make a living (DFID, 2007; Ellis, 2000; Scoones, 2009). An increasing recognition that the ability to pursue different livelihood strategies is dependent on the basic material and social, tangible and intangible assets that people have in their possession (Scoones, 2009). For this reason, some recent studies give more emphasis to factors determining a livelihood strategy. These factors include the biodiversity protection (Salafsky and Wollenberg, 2000), soil fertility (Tittonell et al., 2010), policies (Barrett et al., 2001a), market liberalization, agricultural intensification (Orr and Wmale, 2001), tourism (Wall and Methiesion, 2006; Tao and Wall, 2009; Iorio and Corsale, 2010; Mbaiwa, 2011), cropping, forestry and livestock products (Stoian, 2005; Babulo et al., 2008; Kamanga et al., 2009; Tesfaye et al., 2011; Adam et al., 2013; Diniz et al., 2013; Zenteno et al., 2013), and nat- ural capital (Fang, 2013a). In addition, Alwang et al. (2005), Van den Berg (2010) discussed the dynamics of livelihood strategies in Nicaragua using a multidimensional manner. By identifying determinants of livelihood strategy, they suggested that the approach motivation would be associated with increasing the family welfare of farmers. Through the literature review, the quantitative livelihood approach has become an increasingly popular way of understanding the inter-relationship between livelihood strategies and impact factors. Based on the regression analysis, the relationship between livelihood strategies and consumption is already being observed (Alwang et al., 2005). The impact of labor force and land on livelihood strategies is examined in the study con- ducted by Jansen et al. (2006). Ulrich et al. (2012) descried the causal relationship between livelihood strategies of rural families in Kenya and livelihood capitals portfolio, by employing welfare indexes as a means of quantifying analysis. They concluded that the portfolio of agricultural and husbandry production, stable non-farm activities, and flexible and diversified livelihood capita, might become considerable importance to livelihood strategy. Adam et al. (2013) identified the key factors that influenced rural livelihood strategies and quantified their effects on livelihood strategy. They argued that regulatory, technical and financial support related to non-timber forest products greatly improved the effect of a livelihood strategy.

Similarly, the importance of viewing livelihood capitals as a driving force of livelihood strategy practices is emphasized in the paper prepared by Zenteno et al. (2013). Regarding livelihood strategy, we have seen that insights about the interaction between livelihood strategies and livelihood capitals are crucial to improving our understanding of sustainable livelihood in rural areas.

Natural disasters often undo many years of physical as well as human capital accumulation and can lead to slowing down the speed of convergence towards a steady state economy within the country context. The world has recently faced a sharp surge in the frequency of extremely severe natural disasters, and the effects have been devastating. More than 7,000 major disasters have been recorded since 1970, causing at least USD 2 trillion in damages, killing at least 2.5 million people, and adversely affecting societies (CRED 2010). As stated we can see that disasters can take a toll on all aspects of life, A list of natural Hazards in the Caribbean can be summarized by listing the following: Earthquakes, Volcanoes, Landslides, Flooding (Coastal flooding, River flooding) Tsunamis, Hurricanes.

Coastal communities in Bangladesh are at great risk due to frequent cyclones and cyclone induced storm-surges, which damages inland and marine resource systems. In the present research, seven marginal livelihood groups including Farmers, Fisherman, Fry (shrimp) collectors, Salt farmers, Dry fishers, Forest resource extractors, and Daily wage laborers are identified to be extremely affected by storm- surges in the coastal area of Bangladesh. A livelihood security model was developed to investigate the security status of the coastal livelihood system in a participatory approach. In the model, livelihood security consists of five components: (1) Food, (2) Income, (3) Life & health, (4) House & properties, and (5) Water security. (Mutahara, M., Haque, A., Khan, M.S.A. et al. Stoch Environ Res Risk Assess (2016)

Climate change adaptation in the low laying developing countries is becoming crucial at the present time. However, the local knowledge regarding climate change adaptation is not well focused. However, seasonal livelihood and hazard calendar demonstrated that local people were increasingly changing their livelihood status with changing climatic hazards. At that situation local people tried to adapt themselves with the changing climate through changing their own behavior and introducing some adaptation strategies.

Limited case examples and research have analyzed and highlighted the links between gender norms, roles, relations and health impacts of climate change, adapted from the synthesis report of the International Scientic Congress on Climate Change (McMichael & Bertollini, 2009), is used in this paper to structure the available information on the gendered health implications of climate change, according to (i) the direct and indirect health impacts of meteorological conditions; (ii) the health implications of potential societal ects of climate change, for example on livelihoods, agriculture and migration; and (iii) capacities, resources, behaviours and attitudes related to health adaptation measures and mitigation policies that have health implications

In the past 10 years, the literature on disasters and mental health has shifted from a focus on psychopathology, to an interest in documenting manifestations of resilience in the face of mass trauma. The Jin et al. study, published in this issue of the Journal, examines gender differences in the relationship between posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and posttraumatic growth (PTG) in the aftermath of the Wenchuan Earthquake in China. The study suggests that the coping response to PTSD may differ between males and females, and raises interesting questions about the types of factors that contribute to the manifestation of high versus low PTG given high levels of PTSD. At the same time, this type of study highlights the need to investigate the long-term impact and meaning of PTG, and to examine whether it reflects an adaptive process with long-term benefits in the face of traumatic exposures, or an illusory type of posttraumatic response.

Main A recent review by Nelson (2010) highlights how the concepts of vulnerability and resilience are relative newcomers to climate change adaptation science and policy in Australia. According to Nelson and colleagues, to date, adaptation science in Australia has been built on a hazard and impact modeling tradition. They suggest that this hazard-impact approach is too narrow and technical, and propose that there is an urgent need to broaden this application to include what they regard as more ‘integrated and holistic’ concepts such as how they perceive vulnerability and resilience. In a later work in which they apply these concepts, they suggest that continued reliance on a hazard/impact modeling approach alone can lead to misleading conclusions about vulnerability, with the potential to misdirect policy (Nelson, et al. 2010).

Studies that have applied the concepts of vulnerability and resilience to evaluate ecosystem change, particularly those applied to policy-making, are still few (e.g. Luers 2005; Adger 2006; Eakin and Luers 2006; Nelson, et al. 2007; Walker, et al. 2009; Nelson, et al. 2010). The development of appropriate metrics remains an on-going research need (Adger 2006; Nelson, et al. 2010).

In the spirit of suggesting how these concepts might be further introduced into climate change adaptation science and policy in Australia, I offer some observations on established definitions and applications of these concepts to date in the global environmental change area. I highlight the critical importance of the role of values in underpinning the characterization of ecosystems and any attendant changes. Based on a literature review, I propose that despite progress made on understanding how values underpin these concepts, some key points continue to be overlooked. I offer three propositions to describe how values underpin such concepts. These propositions are not new, and have been made in other contexts (e.g. Allen and Hoekstra 1992; de Chazal 2002; Allen, et al. 2003; Carolan 2006; de Chazal 2010). I elaborate on how these propositions are not adequately accommodated, in particular in relation to ideas of biophysical and social vulnerability, specified versus general resilience, and assignments of desired trend direction (i.e. increasing resilience or decreasing vulnerability). I finish with some suggestions toward better accommodation of multiple and often conflicting values into vulnerability and resilience frameworks, as well as how to achieve a more substantive integration of the natural and social sciences within this domain.

By values I mean individual or collective judgments concerning desired ecosystem states or goals of management. I choose to use the word ecosystem over the more popular term ‘social-ecological’ system. Although I support aspirations and efforts to consider social and ecological systems jointly (e.g. Berkes, et al. 2003; Turner II 2010) I suggest that terms such as ‘human-environment’ or ‘socio- ecological’ can in fact work to separate these domains. I use the term ecosystem in its original sense as first proposed by Tansley (1935), and as embodied in the work of Allen and Hoekstra (1992) and Allen et al. (2003). Ecosystem is therefore a term to characterize interactions between a set of biological and physical components, where humans and their artifacts can be members, and where these interactions lead to some emergent properties that contribute to distinguishing the ‘whole’.

A large number of authors have reviewed the concepts of vulnerability (e.g. Adger 2000; Kelly and Adger 2000; Brooks 2003; Schroter, et al. 2005; Adger 2006; Eakin and Luers 2006; Fussel and Klein 2006) and resilience (e.g. Carpenter, et al. 2001; Walker, et al. 2002; Walker, et al. 2004; Folke 2006; Manyena 2006; Nelson, et al. 2007).

These reviews describe separate evolutions of each concept, with recent efforts directed at bringing the two fields together (Vogel 2006; Nelson, et al. 2007; Turner II 2010). Resilience is understood as emerging from ecology, principally based on ideas by Holling (1973). Vulnerability is understood as having emerged from several traditions in the social and biophysical sciences. Adger (2006) groups these traditions as ‘absence of entitlements’, ‘natural hazards’, ‘pressure and release’ and ‘human/political ecology’. These traditions were originally distinct, however recent efforts have worked to bring them together (Turner, et al. 2003; Turner, et al. 2003; Liu, et al. 2007; Turner II 2010).

In the climate change arena, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) definition, framing vulnerability in terms of exposure, sensitivity and adaptive capacity is the most commonly used (Fussel and Klein 2006).

In the resilience area, the definition by Walker et al. (2004), framing resilience as ‘the capacity of a system to absorb disturbance and reorganize while undergoing change so as to still retain essentially the same function, structure, identity, and feedbacks’, and close derivatives proposed by Berkes et al. (2003) and Gunderson and Folke (2002), are often cited.

The aim of this framework is to conceptualize the following:

Tropical storm: They are organized center of low pressure that originates over warm tropical oceans. The maximum sustained surface winds of tropical storms range

from 63 to 118 km (39 to 73 miltropical storm, organized centre of low pressure that originates over warm tropical oceans. The maximum sustained surface winds of tropical storms range from 63 to 118 km (39 to 73 miles) per hour. These storms represent an intermediate stage between loosely organized tropical depressions and more intense tropical cyclones, which are also called hurricanes or typhoons in different parts of the globe. A tropical storm may occur in any of Earth’s ocean basins in which tropical cyclones are found (North Atlantic, northeast Pacific, central Pacific, northwest and southwest Pacific, and Indian). The size and structure of tropical storms are similar to those of the more intense and mature tropical cyclones; they possess horizontal dimensions of about 160 km (100 miles) and winds that are highest at the surface but decrease with altitude. The winds typically attain their maximum intensity at approximately 30–50 km (20–30 miles) away from the centre of the circulation, but the distinct eyewall that is a characteristic of mature tropical cyclones is usually absent.es) per hour. These storms represent an intermediate stage between loosely organized tropical depressions and more intense tropical cyclones, which are also called hurricanes or typhoons in different parts of the globe. A tropical storm may occur in any of Earth’s ocean basins in which tropical cyclones are found (North Atlantic, northeast Pacific, central Pacific, northwest and southwest Pacific, and Indian). The size and structure of tropical storms are similar to those of the more intense and mature tropical cyclones; they possess horizontal dimensions of about 160 km (100 miles) and winds that are highest at the surface but decrease with altitude. The winds typically attain their maximum intensity at approximately 30–50 km (20–30 miles) away from the centre of the circulation, but the distinct eyewall that is a characteristic of mature tropical cyclones is usually absent. (“Joseph A. Zehnder, 2011).

Hazard: The potential interaction between a physical event (such as a hurricane or an earth- quake) ad a human system; an event that is potentially harmful to people and their assets, and can cause disruption of their daily activities. Hazard includes elements such as potential occurrence, magnitude, frequency, and speed of onset (Wisner, Gaillard and Kelman 2012).

Disaster: A situation in which a hazard actually influences a vulnerable human system and has consequences in terms of damage, loss, disruption of activities, or casualties that are of such a magnitude that the affected people do not have the mechanisms to deal effectively with them (Wisner, Gaillard and Kelman 2012). Note that the definition of hazard emphasizes the potential for damage, loss, and so forth, while the definition of disaster emphasizes their actuality.

Vulnerability: Being susceptible to loss, damage, and injury. The characteristics of a per- son or group and their situation that influence their capacity to anticipate, cope with, resist, and recover from the impact of a disaster (Wisner et ai. 2004).

Risk: The coincidence of hazard and vulnerability, with the potential for harm depending on the degree of vulnerability, including personal and social protection, and on the resources the system can draw from to cope and adapt. As a function of combined elements of hazard and vulnerability, disaster risk combines a hazard’s potential occurrence, magnitude, and frequency with people’s susceptibility to loss, injury, and death (Wisner et al. 2004).

Capacities: The abilities of a person or group to take actions in order to resist, cope with, and recover from disasters (Wisner, Gaillard and Kelman 2012; Wisner et al. 2004). These capacities are based on the availability of and access to various resources and assets people can draw from to face hazards and manage disasters (Brooks and Adger 2005; Eakin and Lemos 2006; Smit and Wandel 2006; Yohe and Toi 2002; Wisner, Gaillard and Kelman 2012; Wisner ei a/. 2004).’»

Political resources and institutions: Political representation and political voice, leadership, development of political capabilities or claims people can make to the state. Critical institutions that promote and support risk and disaster management, along with the way they operate and are structured (for example, transparent decision making, institutional requirements).

This chapter shows the research design and methodology. It gives the study layout, sample selection and size. The chapter also outlines the study methodology and data analysis. It also presents the T.C and D of the research. Lastly it gives a conclusion of the research layout and methodology.

As stated by Strydom, Fouche and Delport (2005:132), a research design is a plan or blue print of how you intend conducting the research. Research design emphases on the end product, formulates a research problem as a point of exit and focuses on the rationality of research.

Huysamen (1993:10) offers a closely related definition of design as the plan or blue print according to which data is collected to investigate the research hypothesis or question in the most economical manner. Other scholars suggest that research design as all decisions made in planning the study, including sampling, sources and procedures for collecting data, measurement issues and data analysis plans.

Additionally, Strydom, Fouche and Delpot (2005:269) argue that the research design used differ depending on the purpose and the study, the nature of the research questions and the skills and the resources available to the researcher. Nevertheless, each of the possible designs has its own perspective and procedures, the research procedure will also reflect the procedures of the chosen design. The qualitative research design is that it does not usually provide the research with a step by step plan or a fixed recipe to follow. In quantitative research the design determines the researcher’s choice and action, while a qualitative research the researcher’s choices and actions will define the design or strategy. Simply putting more qualitative research during the research process will create a research strategy which is best suited for the research. In picking the suitable research design for this study, therefore, the above approaches were taken into consideration. The study employed both quantitative and qualitative approaches. The study was conducted in Coulibistrie community in St. Joseph district in Southern Province. The community was selected because it has experienced floods for three (3) consecutive rainfall seasons. The study had discussions with key stakeholders at district and community levels as well as randomly sampled households at community level.

According to Strydom, Fouche and Delport (2005:193), sampling means taking any portion of a population or universe as representative of that population. It is usually stated that the bigger the population, the smaller the percentage of that population the sample needs to be and vice versa. If the population is reasonably small, the sample should contain a practically larger percentage of the population. Big samples allow researchers to draw more representativeness and accurate conclusions and to create a more accurate prediction than in smaller samples.

Further, Strydom, Fouche and Delport (2005:194) state that the major reason for sampling is feasibility. A thorough coverage of the total population is rarely possible and all the members of a population of importance cannot possibly be reached. Even if it were theoretically possible to identify, contact and study the entire relevant population, time and cost considerations usually make this a prohibitive undertaking. The use of samples may therefore result in more accurate information than might have been obtained if one had studied the entire population. This is so because, with a sample, time, money and effort can be concentrated to produce better quality research, better instruments and more in-depth information.

The target population, therefore, for the study that is, households, institutions and community leaders and practitioners was purposively selected at household, district and community levels respectively. According to Strydom, Fouche and Delport (2005:202), purposive sampling is entirely based on the judgment of the researcher, in that a sample is composed of elements that contain the most characteristics, representative or typical attributes of the population.

Due to time and financial resource limitations, Eighty (80) home out of 128 were randomly sampled and interviewed at community level. A total of five (5) and one (1) Key Informant Interviews were conducted at the village and district levels respectively.

This study will be done using a Qualitative Research Style also using the Livelihood framework system. This is to ensure a comprehensive and adequate understanding and explanation of the research. The study is a comparative study, which will examine patterns of similarities and differences before and after the TS Ericka. According to the Strydom, Fouche and Delport (2005:159), Qualitative data collection methods often employ measuring instruments. measurements refers to the process of describing abstract concepts in terms of specific indicators by the assignment of numbers or other symbol to the indicators while in qualitative research, the researcher’s choices and actions will determine the design or strategy.

As shown above, the study has utilized both quantitative and qualitative approaches for the aim of triangulation. The notion of triangulation bases the pretension that any bias inherent in a particular data source, investigator and method would be neutralized when used in conjunction with other data sources, investigator and methods. The following data collection methods were used:

According to Babbie and Mouton (2001: 233), the basic objective of a questionnaire is to obtain facts and opinions about a phenomenon from people who are informed on a particular issue. Questionnaires are probably the most used generally used instrument of all. In this particular study, primary data was obtained by directly talking to the interviewees at household level so as get very reliable and accurate information.

Data was collected via personal interviews from 80 households randomly sampled from the Coulibistrie village. The households were interviewed at their individual homes and on the field (farms, at the bay and in the village).

The household questionnaire comprised of these topics:

The interviews were carried out with the key informants using a checklist for both district and village levels. The makeup of the key informants consisted of all important players that have a part to play in the management of disasters. Some respectable organizations and individuals at district level included the following:

At village level, the interviewees were representatives of the village. It was imagined that the representatives would give standard perceptions and perspectives on the subject matter. The interviews were conducted at a venue organized within the community.

The key informants and focus group discussions at district and village levels covered the following topics:

According to Strydom, Fouche and Delport (2005:218), data analysis means finding answers by way of interpreting the data and results. To interpret is to explain and find meaning. It is difficult or impossible to explain raw data, one must first describe and analyse the data and then interpret the results of the analysis. Analysis means the categorization, ordering, manipulating and summarizing data to obtain answers to research questions. The purpose of analysis is to reduce data to an intelligible and interpretable form so that the relations of research problems can be studied tested and conclusions drawn. Interpretation takes the results for analysis, makes inferences pertinent to the research relations studied and draws conclusions about these relations. For this study, Data Entry Screens were developed in SPSS for Data Entry Version 3. This applied to the quantitative data collected. The qualitative data was coded and entered into MS Excel before being transported to SPSS.SPSS Windows Version 11.5 was used for the analysis.

Strydom, Fouche and Delport (2005) states that credibility is the alternative to internal validity in which the goal is to demonstrate that the inquiry was conducted in such a manner as to ensure that the subject was accurately identified and described. The aim is to assess the intentionality of respondents, to correct for obvious errors and to provide additional information. It also creates an opportunity to summarize what the first step of data analysis should be and to assess the overall adequacy of the data in addition to individual data points.

In this study, the author was self-assured that the primary data collected is a fair reflection of the problem being studied. The reason being that the method of data collection used gave the author an opportunity to ask probing questions and sought clarifications where it was necessary. Furthermore, by conducting personal interviews, the researcher was confident that the interviewees meant what they said and hence their responses were a true reflection of the impact of floods on the socio-economic livelihoods, the subject of the study.

According to Strydom, Fouche and Delport (2005), transferability is alternative to generalization. This refers to the extent to which the findings can be applied in other contexts or with other respondents. It is the obligation of the researcher to ensure that findings can be generalized from a sample to its target population. From the personal interviews with the sample interviews, it was established that there was some uniformity and consistency in their responses. This in a way gave the researcher the confidence in the community’s responses on the impact of the floods on their socio-economic livelihoods

Strydom, Fouche and Delport (2005) suggests that dependability is alternative to reliability in which the researcher attempts to account for changing conditions in the phenomenon chosen forthe study as well as changes the design created by increasingly refined understanding of the setting. The study must provide its audience that if it were to be repeated with the same or similar respondents (subjects) in the same (or similar) context, its findings would be similar. Since there can be no validity without reliability and thus no credibility without dependability, a demonstration of the former is sufficient to establish the existence of the latter. In terms of this study, the information obtained at community level was triangulated with that obtained from the household level and there was consistence in the data generated.

In conclusion, quantitative and qualitative were both used for the study. Structured and open-ended questionnaires used to gather primary data. Nevertheless, the analysis looked at both the primary and secondary data.

The next chapter outlines the discussion of results.

This chapter gives a discussion on the results of the research based on the primary and secondary data collected. It highlights the events of Tropical Storm Ericka. it as well highlights the results and discussions on the household demographics, livelihoods pattern, impact of floods on various aspect, coping strategies underlying causes of vulnerability, interpretation, limitation and implications of the study. Last but not least, the chapter recommends further research.

The demographics distribution is that out of a total of 80 households sampled during the survey, 52% of the males were head of the households and the remaining 48% were females. Also, 64% of the household heads were married when 8% were widowed. In relation to ages of the household heads, the results of the surveys showed that majority of the household heads between the ages of 40 – 49 as shown below in Figure 4- 1 below.

Source: Field Data, 2016

Figure 4- 1: Age Grouping of Household Heads (Comparative Analysis)

Furthermore, it can be seen that there aren’t a lot of young household heads in the village among those interviewed, Majority of them moved to the city or went abroad. Conditions in the village and after the passing of Tropical Storm Ericka made the situation worst of the young people. Relocation didn’t affect them as much as it did to the older generations.

Source: Field Data, 2016

Figure 4- 2: Household Size (Comparative Analysis)

The research also that household size from the sampled (80) Households was ranging between 3-4 persons (52%) followed by 5-7 persons (25%).

Source: Field Data, 2016

Figure 4- 3: Chart showing the Ages of Household heads

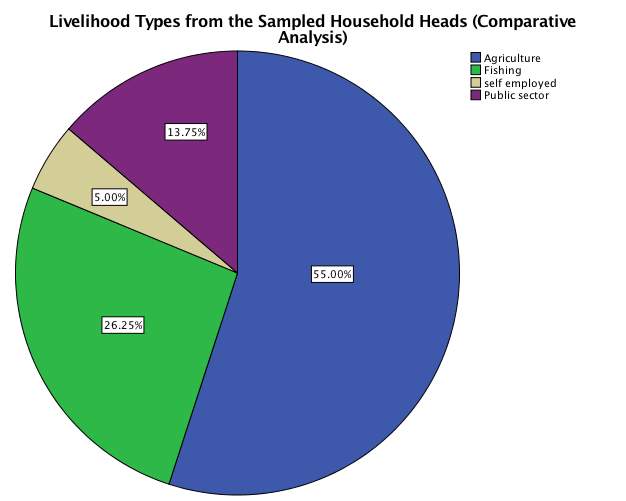

This research has shown that some of the most important livelihoods for the evaluated village of Coulibistrie are Agriculture (crop production) 55% followed by Fishing 26.25% and then the public sector (wage pay)13.75%. The interviews and discussions done at the village established that the main source of revenue for majority of the households was Agriculture then followed Fishing and Self-Employment. A lot of the food consumed by the people was self-produced for example the tomatoes and fruits along with ground provision, followed by fishing. The effect of such is that since agriculture is one of the main sources of livelihood and nutrition, when Ericka hit the village it damaged majority of the produce compromising their food security.

Source: Field Data, 2016

Figure 4- 4: Livelihood types from the sampled household heads (Comparative Analysis)

It was noted that the marital status of the head of the house played a very important part in the choices of livelihood strategies. The ones who were married had variety of different livelihoods as to those who were single, separated or widowed or Divorced. In Addition, just a small percentage of the households sampled did not rely on crop production as a livelihood source.

The research shown that the households with family size ranging from 6-7 had more diversity in relation to livelihood options. In the event of the tropical storm they were able to employ an alternative livelihood option to reduce the effects.

Each and every one of the samples households indicated the availability of the education facility in the village which is a Primary School, and 100% of them knew where the the primary school located in the village was completely destroyed by the Tropical storm, All the families that had children attending this Primary school had to temporarily send them to the primary school in the neighboring village for approximately one (1) year while repairs were being made to the local primary school. The ones who attended other educational facilities in other parts of the country had issues in terms access, as the village was completely cut off from the rest of the country for a period of time.

The research revealed that majority of the sampled households (96%) indicated that health facilities were available in their communities. Furthermore, very few households (2%) had indicated that health facilities had been damaged by flooding in their communities. The study further revealed that 32% of the sampled households experienced disruption in access to health services due to damaged roads and bridges as a result of floods.

The study found that household heads faced a disruption in accessing health services as a result of damaged roads and bridges, also the village was completely cutoff from the rest of the country so it was impossible for people to get in or out and during the time the health center also faced damaged from Tropical Storm Ericka.

From the eighty (80) households sampled 100% of them reported some sort of damage was done to their homes, throughout observations it was noted that a total of 12 homes were totally destroyed, these people who lost their homes some were relocated by the government and the remaining either moved in with family or friends in and out of the village. There was government assistance of a total of 3000 EC dollars.

In Figure 4- 11 above it can be seen that one of the villagers’ home were being rebuilt, but one of the issues that this might face is that it is in the same location as the pervious house and the material used, both aren’t the best given the current situation. The location; it’s still in the path of the river if it overflows the banks and the material used is wood which is not durable.

The sampled village showed a bit of diversity on the different types of drinking water sources that came about after the passing of Tropical Storm Ericka. It was shown by data collected that pipe bourn water and the river was main water sources that the people in the village used for drinking.

The survey indicated that (67.5%) their main source of drinking was pipe borne and then followed by the river and water drums at (32%). To Further emphasize everyone reported a disruption in their drinking water source was affected by Tropical Storm Ericka.

In the above figure, the picture shows the section of the river which has been contaminated by the water pipes which were destroyed and got into the stream over the past year the metals that these pipes are made of has been rusting and running off into the water causing it to be contaminated and unfit for human consumption. This has also been the reason behind the lack of Pipe Bourne water in the village as the water catchment area was also destroyed during the passing of Tropical Storm Ericka.

The study also showed that a large number of both productive and non-productive assets were destroyed or damaged by Tropical Storm Ericka. In the case of productive assets, the following were lost, fishing boat engines, nets, pots and other equipment’s, also private businesses lost tools and goods during that time. In the case of non-productive assets beds, televisions and other household appliances were either damaged or totally destroyed. A lot of these losses were causes by the location of these homes and businesses as they were mainly right along the riverbanks of which it overflowed during that time. Throughout discussions it was also pointed out that some of the households had to sell some assets as their normal livelihoods were disrupted due to Tropical Storm Ericka.

Majority of the people interviewed (100%) said that their farm lands were damaged of completely lost because of the tropical storm. It was also clear to note that the farm lands that were destroyed 100% was their cash crops. While no data was collected on the amount of area cultivated for agriculture was collected, it was clear that the impact on agriculture which was and still is the main source of their livelihood and income as mentioned in the livelihood patterns.

Out of the 80 sampled households, 100% indicated having experienced food stock losses due to disaster. The research also revealed that within the households whose crops and food stocks were damaged by the floods, 93% resided in the disaster prone areas of the Coulibistrie, luckily for some of the farmers they had farm lands in out villages so they still had something to rely on but still with some difficulties as they are very far from their homes and the trip going back and forth adds an extra cost to their daily live in relations to time, money, and productivity.

The Study and survey has shown that the sampled households implemented a set of different coping strategies due to the passing of Tropical Storm Ericka. One to the most important Coping Strategies were the drenching of the river, followed by relocation thou some of the villages rebuilt their houses in the same exact location even thou the location wasn’t ideal, some of the villagers tried to build a wall around their property in other to try and keep the water out.

It was established that the households whose coping strategies were relocation, they 50% of them had the help of the government who helped by offering a housing scheme in other villages/ communities. The remaining groups of people received a small compensation to replace damage appliances in their homes in the amounts of $ 3000 – $5000 EC dollars Main body text Main body text Main body text Main body text Main body text Main body.

There were different underlying causes of vulnerability to Tropical Storm Ericka for majority of the people in Coulibistrie area. Closeness to the river area, dwelling right along the river banks and poverty were pointed out as being the main underlying causes of vulnerability by the Coulibistrie village.

From the results of the analysis it is clear to see that Tropical Storm Erick Had a huge impact on the livelihoods of the people in these key aspects, to name a few, agriculture, health, education and water etc.

The main source of livelihoods of the studied households was agriculture followed by Fishing and self-employed. The survey stated that over 95% of the people had their produce damaged. Along with some actually losing their lands.

The discoveries from the study have effects for the development of the people in Coulibistrie village and the nation as a whole. Disasters such as Tropical Storms demand that efforts should be directed at formulating sustainable mitigation measures. Appropriate improvement measures considered under the recommendations section should be implemented in order to enhance community resilience in view of climate variability. Thus the need to continuously assess the flood risk cannot be overemphasized.

The identification for mitigation measures should not only involve the vulnerable communities but all stakeholders including the Private Sector and Civil Society.

There should be adequate finding towards risk mapping, monitoring and implementation of preparedness and mitigation measures.

Investment in flood management, taking into account climate variability should be a priority. Further community awareness on the flood risk itself should be promoted.

During the research there was some limitations as stated below:

The general objective of the study was to assess the Socio-economic Impacts of Tropical Storm Erika on the people in St. Joseph, Coulibistrie village and their adaptation strategies. While no real economic data was gathered it is clear from the responses and observations made that, any impact therefore on livelihood would result into reduced income and reduced spending power for people.

The factors that governs the underlining origin of vulnerability have been recognized and coping strategies and development identified.

The discoveries from the study have implications for the development of the people in Coulibistrie. Natural disasters such as Tropical Storms demand that efforts should be focused at preparing sustainable mitigation measures.

The identification for mitigation measures should not only involve the village of Coulibistrie but all stakeholders plus the Private Sector.

There should be adequate finding towards risk mapping, monitoring and implementation of preparedness and mitigation measures.

Investment in disaster management, taking into account climate unpredictability should be set as a priority.

This Chapter conclusion and recommendations that aroused from the research. The study reviewed a large group of literature and collected primary data via which the conclusions and recommendations are based on. The research was guided by the Disaster Risk Reduction Conceptual framework which stresses on a forward-looking approach to disaster management. It is very important that villages adopt a risk reduction path to the effects of tropical storms/ hurricanes. The research strived to answer these following questions:

The conclusions and recommendations are showed below.

As discussed under numerous areas and sections. It’s clear from the research that tropical storms/ hurricanes had adverse impact on the socio- economic position of the livelihoods for the people in the Coulibistrie village of St. Joseph district. To a great degree, the research has shown that livelihood patterns has a significant role to play in the settlement patterns. It has shown distinct proof that there are different underlying causes of the people vulnerability and this gives a challenge for the reduction or minimization of the given situation.

For those settled along the river bank and those in poverty it was concluded as being the main cause of vulnerability by the Coulibistrie village. The research has also demonstrated the effects of tropical storms/ hurricanes in one area can affect the other parts of society.

The study has further demonstrated that effects of tropical storms/ hurricanes in one sector can affect other sectors of society. For instance, as discussed under the health section, the outbreak of disease incidences (diarrhea and coughing) was attributed to the impact of the floods that occurred during the Tropical Storm on water sources and sanitation facilities.

The problem of water contamination in the river and lack of pipe water increases the health risk. Also, in spite of the fact the health center wasn’t damaged during the disaster, accessibility to the health services was an issue due to the damaged that was done to the roads and bridges in the village, the amount of damage was mentioned in the health section. To add the primary school couldn’t be used as it was totally destroyed and this was also discussed in the area of education in chapter 4.

From research done it was easy to conclude that the households cope/ managed differently when it came to dealing with the effects of the tropical storm/ hurricanes. The present managing systems being used by most households aren’t very reliable. Discussions at village and district levels stated that the managing systems (copping) weren’t sustainable because they had been using them and their situation didn’t seem to improve. The current village management systems (coping) Shouldn’t be underestimated or discarded but but be helped in improvements. The villagers should be advised to build houses that are more durable and away from the path of the river. Furthermore, the ministry of Agriculture should better educate and advise the farmers of the village.

Clearly, there is an urgent need to create better and more useful measures (this is discussed in the flowing two sections below) to be readily prepare and mitigate the aftermath of the disaster. All in all, the main aim is to include everyone to improve villages resilience to tropical storms and hurricanes.

It is crucial in this section of the paper (chapter) to highlight the main or some policy considerations which if applied can play a very important role in the management of damage control. These policies are the following which could be considered:

Questionnaire

Socio-economic Impacts of Tropical Storm Erika on the people in St. Joseph, Coulibistrie village and their adaptation strategies

Date:

Section A

Livelihoods

Impact of Tropical Storm Ericka

| Areas | Level of Damage | Comments | |

| Crop (Production) | |||

| Crop (Stocks) | |||

| Livestock | |||

| Health | |||

| Water | |||

| Property | |||

| Housing | |||

| Infrastructure | |||

Main causes of Vulnerability to Tropical Storms

Coping strategies

| Positive | Negative |

Section B

Suggestions/ Comments

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

Household Interview/Questionnaire

Socio-economic Impacts of Tropical Storm Erika on the people in St. Joseph, Coulibistrie village and their adaptation strategies

Section A

Household Demographics

Livelihood Patterns

______________________________________________________________.

Impact of Tropical Storm Ericka

Housing

_______________________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________________

Property/ Asset

___________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________

Agriculture

________________________________________________________________.

________________________________________________________________.

Education

________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________.

________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________

Health

________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________

________________________________________________________________

Water

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

Vulnerable Groups during Tropical Storm Ericka

Coping strategies

Section C

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

Section D

Suggestions/ Comments

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

You have to be 100% sure of the quality of your product to give a money-back guarantee. This describes us perfectly. Make sure that this guarantee is totally transparent.

Read moreEach paper is composed from scratch, according to your instructions. It is then checked by our plagiarism-detection software. There is no gap where plagiarism could squeeze in.

Read moreThanks to our free revisions, there is no way for you to be unsatisfied. We will work on your paper until you are completely happy with the result.

Read moreYour email is safe, as we store it according to international data protection rules. Your bank details are secure, as we use only reliable payment systems.

Read moreBy sending us your money, you buy the service we provide. Check out our terms and conditions if you prefer business talks to be laid out in official language.

Read more