Reforming School Discipline Policy

Alternatives to Exclusionary Student Discipline

Student discipline is necessary for cultivating school environments that are safe, welcoming, and supportive. The California Constitution guarantees a system of free schools to children of the state[1] and the California Supreme Court determined that education in California is a fundamental right.[2] A serious issue that affects this fundamental right is harsh punitive student discipline. Research shows that harsh punitive student discipline practices and policies don’t improve school safety or improve student success.[3] Instead, these harsh practices force students to leave school voluntarily by dropping out early or forcing them to leave school and abandon their education. Harsh punitive discipline policies that include exclusionary discipline such as suspension, in-school suspension, expulsion, and involuntary transfers disproportionately affect male students of color and students with disabilities more than other student populations. In response to these disparities in discipline, different approaches have been adopted and implemented in school districts across the nation including California to foster positive, healthy, and equitable school climates that are conducive to teaching and learning. California offers a model for other states and school districts across the nation to follow in reforming traditional exclusionary student discipline and instead adopting positive student discipline practices that are more effective in improving school safety and student success all while keeping students in school.

In Part I, this paper provides a brief overview of the various forms of student discipline and how they generally relate to procedural due process. Parts II and III provide a deeper analysis of due process rights generally and in California with an emphasis on suspension, in-school suspension, expulsion, and involuntary transfers. In Part IV, this paper discusses the disproportionate affect that harsh exclusionary discipline practices have on minority and disabled students. Lastly, Part V contains policy proposals to reform school discipline policy and encourage school districts nation wide to adopt and implement alternative measures to the traditional exclusionary student discipline methods.

I. Forms of Discipline

There are various forms of student discipline that range in severity such as detention, community service, exclusion from athletic and extracurricular activities, exclusion from school buses, suspension, expulsion, involuntary transfers to alternative schools, and to some extent even corporal punishment.

School staff may use detention for disciplinary reasons during recess, lunch, after school, and weekends. School officials can require students to perform community service on school grounds during non-school hours. School officials can also require students to perform community service off school grounds with written permission from the student’s parent or guardian. School officials may also deny a student from participating in athletic and/or extracurricular activities as disciplinary action. When student misconduct happens on school buses, the school district may take disciplinary action by suspending the student’s bus transportation for a period of time.

There are various types of suspensions such as in-school suspensions, which is when students are assigned to a supervised suspension classroom for the period of the suspension. In school suspensions are used for minor infractions where the student does not pose an imminent danger or threat to the campus, pupils, and staff. There are also short-term suspensions that remove a student from a school for 5 or 10 days. The number of days that constitute a short-term suspension differs from state to state. Anything above the 5-10 day short-term suspension would be considered a long-term suspension and are used when recommending a student for expulsion.

Expulsion is the removal of a student from a school and/or school district for an extensive period of time for severe offenses. In contrast to long-term suspensions and expulsions, a school district may transfer a student to an alternative school where the setting is presumed to accommodate for the behavioral needs of the student that cannot be adequately addressed in the traditional school environment the student was transferred from.

Most states have laws that prohibit the use of corporal punishment to discipline students. For example, California’s law states that no student shall be subject to the infliction of corporal punishment by any person employed by or engaged in a public school.[4] The statute defines corporal punishment as the willful infliction of, or willfully causing the infliction of, physical pain on a pupil. It’s important to note that a person employed by or engaged in a public school may use an amount of force that is reasonable and necessary to quell a disturbance threatening physical injury to a person or damage to property, for purpose of self-defense, or to obtain The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution states, “No state shall deprive any person of life, liberty or property, without due process of law.”[5] In 1954 in Bolling v. Sharpe[6], the Supreme Court recognized that the word “liberty” encompassed a child’s right to a public education. Today, procedural due process for detention, community service, exclusion from athletic and extracurricular activities and school buses, and in-school suspension is limited. For the most part, school officials need only provide notice to students and parents/guardians of the disciplinary action. School officials hold a lot of discretion and students generally hold little power to provide evidence and rebut the allegations in these types of disciplinary action. Nevertheless, procedural due process for more severe discipline such as suspension, expulsion, and involuntary transfers has come a long way since the 1950’s although a lot of progress can still be made.

II. General Due Process Rights

a. Due Process Rights for Suspensions

Twenty-one years after the Supreme Court held that education was a property interest that the due process clause protected in Bolling, the Supreme Court addressed the procedural due process rights of students in Goss v. Lopez.[7]In Goss, the Supreme Court established that the Due Process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment requires students facing short term suspensions (10 days or less) to be provided oral or written notice of the charges against them, and if students deny the charges, then an explanation of the evidence against them, and an opportunity for students to respond to the accusation. In Goss, the Columbus, Ohio Public School System argued that since there was not a constitutional right to a public education, then that meant that there could not be a constitutional protection against suspensions without some type of hearing from a public school. The Court rejected this argument and stated that “the Fourteenth Amendment’s general protection of life, liberty, and property interests does not create specific constitutional rights. Rather, specific protected rights are defined by independent sources such as state statutes or rules entitling citizens to certain benefits.” In this case, since the state of Ohio had chosen to extend the right to an education, Ohio couldn’t withdraw that right on grounds of misconduct without fair procedures to determine whether the misconduct occurred. The Court held that the state is required to recognize a student’s legitimate entitlement to a public education as a property interest protected by the Due Process Clause.

The dissent’s opposing view was that a student’s interest in education was not infringed by a suspension amounting to 10 days or less, and that even if there was an infringement, that it was too speculative, transitory, and insubstantial to justify the imposition of a new constitutional rule. Even more alarming, was Justice Powell’s opinion that because the Ohio suspension statute authorized only a maximum of 8 school days, which was less than 5% of the 180-day regular school year, the limited duration absences did not affect a student’s opportunity to learn or their scholastic performance. In his opinion, it was common knowledge that maintaining order and reasonable decorum in schools and classrooms was a major educational problem. That teachers, in protecting the rights of other children to an education and the safety of all those in the room, was compelling enough to rely on the power to suspend. He was of the mind that teachers and administrators would not have time to do anything else if they were required to have hearings before suspending a student. He further believed that student discipline not only shaped students’ characters and personalities, but that it also provided an early understanding of the relevance to the social compact of respect for the rights of others, and he believed that the classroom was the best “laboratory” to learn this “lesson of life.”

Goss is significant today because it still applies the baseline procedural due process requirements for school officials to follow when issuing short-term suspensions on students. Although I generally agree with the way it was decided, I do believe that it is too dismissive of students’ rights. Requiring school officials to provide notice and offer students an opportunity to respond does not offer students much protection and still affords school officials with a lot of discretion when suspending students and depriving them of valuable instructional time in the classroom.

b. Due Process Rights for In School Suspensions

In Laney v. Farley[8], a school imposed a one-day, in-school suspension upon a student for having her cell phone on and it ringing in class. The Sixth Circuit, like other courts, held that in-school suspensions do not implicate a student’s property interest in a public education because students remain in a school setting and are expressly required to complete academic requirements. They reasoned that unlike students in out-of-school suspensions, students under in-school suspensions are not denied all educational opportunities just because they are removed from their classroom. This is still true today in majority of states and school districts. I do not believe that Laney was rightfully decided because although students remain in a “school setting” they are still excluded from traditional classrooms and miss the opportunity to learn the planned curriculum. Students are indeed denied all educational opportunities because although they are being supervised in a classroom, they are not being taught by a teacher and are not able to keep up with the lesson plans.

c. Due Process Rights for Expulsions

In 1961 in Dixon v. Alabama State Board of Education[9], the Fifth Circuit held that the due process clause requires notice and some opportunity for a hearing before students at a public college could be expelled for misconduct. Dixon is relevant today because it sets the minimum requirements for student expulsions. Fortunately, states and school districts have additional requirements in place before school officials can expel a student. Again, I generally agree with the decision in Dixon but feel that it is too vague and broad. The Fifth Circuit could have provided additional guidance and a more in-depth analysis of what is required of school officials and what rights are afforded to students at expulsion hearings.

d. Due Process Rights for Involuntary Transfers

In Buchanan v. City of Bolivar[10], the Sixth Circuit, like other courts, suggested that transfers to alternative schools do not trigger due process protection absent a showing that the education delivered there is significantly inferior.[11] On the other hand, the Ninth Circuit, the Second Circuit, and the Seventh Circuit have issued decisions that treat involuntary transfers as an expulsion even though an alternative educational program was provided. In recognizing that involuntary transfers implicated a student’s constitutionally protected interest in receiving a public education, and that there was significant harm to that interest, the courts applied the full due process protections awarded to expulsions.[12] I agree in part with the Sixth Circuit because it afforded students due process rights in involuntary transfers when the alternative education was lacking and deficient, but I think it was too dismissive of students’ rights. I agree more so with the other Circuits because I think involuntary transfers should automatically trigger due process rights and should have the same procedural protections that expulsions do. The inferiority of the education being delivered at alternative schools should be an important factor to be considered at involuntary transfer hearings.

e. Additional Due Process Rights

In addition to the requirements established inthe cases above, the courts have given us additional guidance in regards to other due process questions such as who can be a due process hearing officer, who has the burden of proof, can students appeal a decision/punishment, can students cross-examine accusers, do students have a right to counsel, do school officials need to provide detailed notice, and whether transcripts are required.

Schools need to have an impartial decision maker that acts in an unbiased capacity conduct the due process hearings. This person does not need to be a third party and may be a teacher or administrator that works for the school.[13] Various courts have also indicated that school officials have the burden of proof and that they need substantial evidence to justify their decision to punish a student.[14] This substantial evidence standard requires the decision maker to increase the cross-examination value or collect additional outside evidence when the existing evidence is conflicting. Many state statutes and local district policies afford the students a right to appeal to the school board for long-term suspensions/expulsions but not for short-term suspensions. A few courts have found that cross-examination is warranted in long-term suspension hearings or when the statements of witnesses are inconsistent.[15] Other courts have rejected cross-examination because they believe that students will use it as a means to intimidate the accuser(s).[16] Some courts have found that students might have the right to have counsel present only to advise the student, but not to represent and speak on behalf of the student or to cross-examine witnesses.[17] As for how detailed notice needs to be, basic verbal notice is sufficient for minor punishments including short-term suspension, but more formal notice is needed with long-term suspensions. A more detailed notice includes more than a conclusory statement of a violation, it needs to have enough specificity and detail for the student to have the information necessary to respond and/or rebut the violation.[18] As for transcripts, records such as notes or summaries of the proceedings are generally sufficient and courts do not typically require transcripts or recordings of the hearings.

While these requirements do offer students additional protections, the requirements are still too dismissive of students’ rights and leave a lot of discretion to school administrators when disciplining students. It is important to note that these additional requirements generally only apply to what school districts and states consider more severe student discipline such as suspension and expulsion. There is very little protection for what states and school districts consider minor student discipline and although these types of discipline also have a negative and disproportionate impact on students. Fortunately, states and school districts have set higher standards and requirements than the baseline for school officials to follow when disciplining students.

III. Due Process Rights in California

a. Suspendable and Expellable Offenses

In California, there are three categories of offenses for which students may be suspended and/or expelled for from a school. Under the first category, school officials have no discretion and they are mandated to suspend and recommend a student for expulsion if the student commits one of five offenses: (1) possessing, selling, or otherwise furnishing a firearm; (2) brandishing a knife at another person; (3) unlawfully selling a controlled substance; (4) committing or attempting to commit a sexual assault or committing sexual battery; or (5) possession of an explosive.[19]

Under the second category, it is expected for school administrators to recommend expulsion unless expulsion is inappropriate due to particular circumstances. A student shall be recommended for expulsion if he or she commits one of the following offenses: (1) causes serious physical injury to another person not in self-defense; (2) is in possession of any knife, explosive, or other dangerous object of no reasonable use to the student; (3) is in possession and/or use of any substance listed in Chapter 2 of Division 10 of the Health and Safety Code, except for the first offense for possession of not more than one avoirdupois ounce of marijuana other than concentrated cannabis; (5) assault or battery, or threat of, on a school employee.

Under the third category, school officials have the discretionary power to suspend a student. A student may be recommended for expulsion if he or she: (1) inflicted physical injury; (2) possessed dangerous objects; (3) possessed drugs or alcohol; (4) sold look alike substance representing drugs or alcohol; (5) committed robbery or extortion; (6) caused damage to property; (7) committed theft; (8) used tobacco; (9) committed obscenity, profanity, and/or vulgarity; (10) possessed or sold drug paraphernalia; (11) disrupted or defied school staff; (12) received stolen property; (13) possessed an imitation firearm; (14) committed sexual harassment; (15) harassed, threatened, or intimidated a student witness; (16) sold prescription drug Soma; (17) committed hazing; (18) engaged in an act of bullying, including, but not limited to, bullying committed by means of an electronic act, directed specifically toward another student or school staff.[20]

California lays a good foundation for other states and school districts to build on. Arguably, California can build on its own existing policy and continue groundbreaking work towards the goal of positive student discipline and keeping students in school by eliminating categories two and three. Limiting zero tolerance policies to category one offenses and dispensing with the expectations and discretion of school officials to use exclusionary discipline practices would force school administrators to find positive and accountable approaches for changing student misbehavior. Shortening the list of suspendable and expellable offenses would go a long way in keeping all students in school. More importantly, it would help keep male students of color and students with disabilities in the classroom.

b. Limits on Suspension and Expulsion

In California, there are safeguards in place when it comes to suspensions and expulsions. Students may only be suspended for conduct related to a school activity. Suspendable and expellable acts can occur at school, at a school activity, or on the way to and from school or the school activity. This places some limits on suspensions and expulsions because a student cannot be suspended or expelled for conduct that happens off-campus that is unrelated to a school event or activity.

California restricts the number of days for which a student may be suspended from school to a maximum of 20 school days in any school year. If a student transfers to another school, then the maximum days that a student may be suspended for in one school year is 30 school days.[21] The number of days that constitute a short-term suspension in California is 5 days. Students may not be suspended for more than 5 days, unless they are being recommended for expulsion. Schools cannot suspend students for absences or tardiness. Although schools have a lot of discretion when it comes to suspensions for the “catch-all” category of willful defiance, there are now some important limits on that discretion. Schools cannot suspend students below the fourth grade from school for willful defiance. Additionally, schools cannot expel any student for willful defiance regardless of grade.

In California, suspensions and some expulsions shall be imposed only when other means of correction have failed to bring about proper conduct.[22] The state offers a number of alternative means of correction such as: (1) a conference between school staff, the student’s parent or guardian, and the student; (2) referral to the school counselor, psychologist, social worker, child welfare attendance personnel, or other school support service personnel for case management and counseling; (3) study teams, guidance teams, resource panel teams, or other intervention-related teams that assess the behavior, and develop and implement individual plans to address the behavior together with the student and parent or guardian; (4) referral for a comprehensive psychological or psychoeducational assessment, including for purposes of creating and individualized education program or plan; (5) enrollment in a program that teaches prosocial behavior or anger management; (6) participation in a restorative justice program; (7) a positive behavior support approach with tiered interventions that occur during the school day and on campus; (8) after-school programs that address specific behavioral issues or expose the student to positive activities and behaviors; and (9) community service.[23]

The limit that California enacted on suspensions and expulsions for willful defiance was a landmark because it was the first law of its kind in the United States. Willful defiance accounts for almost half of all suspensions and it is the offense category with the most significant racial disparities.[24] We can combat disparities in student discipline that disproportionately affect minority and disabled students if we enact similar laws nationwide. California sets another great example and precedent for other states to follow by imposing schools to use other corrective measures before suspending and expelling a student.

c. Due Process Rights for Suspensions in California

The procedural due process requirements for suspensions in California do not differ much from the general requirements set out in Goss. If schools try and fail to correct student misbehaviors using alternative measures, then suspensions shall be preceded by an informal conference conducted by the principal or the principal’s designee between the student and the school staff who referred the student to the principal. At the conference, the student should be informed of the reason for the disciplinary action and the evidence against them, and the student should be given the opportunity to present their version of story and any evidence in their defense.[25] The only way that a school official can suspend a student without first holding a conference is in an “emergency situation.” This means a situation that constitutes a clear and present danger to the life, safety, or health of students or school staff. If a student is suspended without a conference, the school should notify both the student and parent/guardian of the student’s right to a conference and to return to school for the purpose of such conference. The conference shall take place within two school days unless the student waives this right or is physically unable to attend for any reasons. If the student is physically unable to attend, the conference should take place as soon as the student is physically able to attend the conference.[26] School staff should make a reasonable effort to contact the student’s parent or guardian in person or by phone and must notify them of the suspension in writing.[27] School officials should follow district policy or regulation when reporting student suspensions to the Superintendent of Schools and/or the Board of Education.[28] Like California, most states and school districts have similar conference requirements for suspensions. What sets California apart is its noteworthy precedent in limiting schools’ use of willful defiance and requiring them to use alternative correction methods before allowing them to suspend a student.

d. Due Process Rights for In-School Suspensions in California

A student suspended from school for any of the reasons enumerated in Sections 48900 and 48900.2 of the California Education Code may be assigned to a supervised suspension classroom by the principal or a principal’s designee.[29] Students assigned to supervised suspension classrooms need to be separated from other students.[30] School districts are allowed to claim apportionments for students assigned to in-school suspension because the supervised classroom is staffed as provided by law, students have access to counseling services, and students are encouraged to complete schoolwork and tests missed by the student’s suspension.[31] Schools are required to notify parents/guardians of the supervised suspension in person or by phone when a student is assigned in-school suspension for one period, but if the student is assigned in-school suspension for longer than one class period then the school is required to notify parents/guardians of the supervised suspension in writing.[32]

I believe that in-school suspensions should be afforded the same due process legal requirements as out of school suspensions. In-school suspensions do not substantively differ from out of school suspension in terms of the loss of educational opportunities to students. Students assigned in-school suspensions suffer the same educational loss as students assigned out of school suspensions because both students are excluded from the classroom and miss out on important and valuable instructional classroom time. This form of disciplinary action significantly contributes to the growing disparities in student discipline when students of a particular demographic group are repeatedly assigned in-school suspension for both short and long periods of time.

e. Due Process Rights for Expulsions in California

In order to expel a student under categories two and three on the list of suspendable and expellable offenses above, the administrator’s recommendation for expulsion shall be based on a finding that other means of correcting the student’s behavior are not feasible or that the school has tried and failed to correct the behavior and/or that due to the nature of the act, the student’s presence at the school is dangerous to the student or to others.[33] Additionally, if a student is expelled for an offense not included in category one, then school officials must set a date no later than the last day of the semester following the semester that the student got expelled, where they will review the readmission of the student to the last school the student attended or another school in the same district. School officials also need to create a rehabilitation plan for the student at the time of the expulsion. This plan needs to be tailored to the student’s specific needs and may include recommendations for improved academic performance, tutoring, special education assessments, job training, counseling, employment, community service, or other rehabilitative programs.[34] School administrators need to adopt rules and regulations that establish a process for readmissions, and they need to provide the student and parent/guardian with a copy of the procedure at the time of the expulsion.[35]

f. Additional Procedural Protections for Expulsion

Students recommended for expulsion are entitled to a hearing to determine whether they should be expelled. This hearing should be held within 30 schooldays from the date that the principal determined that the student committed an expellable offense. The student can submit a written request to postpone the hearing for up to 30 days. Any additional postponements may be granted at the discretion of the school district.[36] The Board of Education should decide whether to expel the student or not within 10 schooldays after the hearing, unless that time requirement is impracticable during the school year or summer recess.[37] The student should be provided with written notice of the hearing at least 10 calendar days before the date of the hearing. The notice should include the date and location of the hearing, a statement of the specific facts and charges upon which the proposed expulsion is based, a copy of the disciplinary rules of the school district that relate to the alleged violation, a notice of the student’s obligation to inform other school districts of their expelled status upon enrollment, and notice of the opportunity for the student or parent/guardian to appear in person or to be represented by legal counsel or by a nonattorney adviser, to inspect and get copies of all documents to be used at the hearing, to confront and question all witnesses who testify at the hearing, to question all other evidence presented, and to present oral and documentary evidence on the student’s behalf, including witnesses.[38] The Board of Education should conduct the hearing in closed session, unless the student requests in writing that the hearing be conducted at a public meeting.[39] The Board of Education may meet in closed session for the purpose of deliberating and determining whether the student should be expelled, but if they allow any other person to be present at a closed deliberation session, then the student, their parent/guardian, and counsel will also be allowed to attend the closed deliberations.[40]Additional requirements exist for contracting with other agencies to conduct the hearings and special requirements are imposed for hearings with charges of committing or attempting to commit a sexual assault.[41]

The technical rules of evidence do not apply to expulsion hearings, but relevant evidence may be admitted and given probative effect if it is the kind of evidence upon which reasonable persons are accustomed to rely in the conduct of serious affairs.[42] The decision of the Board of Education to expel a student should be based upon substantial evidence, no evidence to expel should be based solely upon hearsay evidence.[43] School districts are required to create and maintain a record of the hearing, and the expulsion order and the cause for the expulsion should be recorded in the student’s mandatory interim record, and should be forwarded to any schools that the student subsequently enrolls in after the expulsion.[44]

g. Due Process Rights for Expulsion Appeals in California

The expelled student or the student’s parent/guardian may file an expulsion appeal to the county board of education within 30 days following the decision of the governing board to expel. The county board of education should hold the hearing within 20 schooldays following the filing of a formal appeal request.[45] A county board of education may have a hearing officer or an impartial administrative panel conduct the appeal hearing.[46] The manner of the expulsion appeal hearings is the same as the expulsion hearings, they must be held in closed session unless the student requests that it be conducted at a public meeting and the same rules apply. It is the responsibility of the student to submit a written transcript for review by the county board for purposes of the appeal. The student must pay the costs and fees associated with the transcript unless the student’s parent/guardian certifies to the school district that they cannot reasonably afford the cost of the transcript because of limited income or exceptional necessary expenses, or both. If the county board reverses the decision of the local governing board, the local board should reimburse the student for the cost of the transcripts.[47] The appeal board is limited in its scope of review to the following questions: (1) whether the governing board acted without or in excess of its jurisdiction; (2) whether there was a fair hearing before the governing board; (3) whether there was a prejudicial abuse of discretion at the hearing; and (4) whether there is relevant and material evidence which, in the exercise or reasonable diligence, could not have been produced or which was improperly excluded at the hearing before the governing board.[48] The county board may remand the matter to the governing board for reconsideration and may in addition order the student reinstated pending the reconsideration. The county board may also grant a hearing de novo upon reasonable notice to the student and the governing board. In all other cases, the county board will enter an order either affirming or reversing the decision of the governing board. If the county board reverses the decision, they may direct the local board to expunge the record of the student with any references to the expulsion.[49] The decision of the county board is final and binding upon both the student and the governing board.[50]

The procedural due process requirements for expulsions in California also do not differ much from the general requirements set out in Dixon. Like California, most states and school districts provide more in-depth procedural guidelines for expulsions and even go a step further in adopting and implementing procedural guidelines for expulsion appeals.

h. Due Process Rights for Involuntary Transfers in California

Transferring students to an alternative educational program involuntarily is intended to be a last resort. California permits involuntary transfers but requires school officials to meet several procedural safeguards to initiate and complete the transfer correctly and legally. First, the Board of Education must adopt rules that include the necessary steps prior to imposition of involuntary transfers, limits on involuntary transfers, and procedural protections for involuntary transfers. Involuntary transfers may be based on any suspendable or expellable offense as well as habitual truancy or irregular attendance. Like suspension and expulsion, involuntary transfers should only be imposed after other means to improve the student’s behavior have failed, unless the school principal determines that the student’s presence at school causes a danger to persons or property or threatens to disrupt instruction. The state also limits involuntary transfers by prohibiting them to extend beyond the end of the semester following the semester during which the transfer was made. In the cases involving involuntary transfers, the school must send written notice to the student and parent/guardian and must provide an opportunity for the student or parent/guardian to request a meeting prior to the transfer. If the student and/or parent/guardian requests a hearing, a meeting must be held where the student and/or parent/guardian has a right to inspect all documents on which the school is basing its decision; question the school’s evidence and any witnesses the school uses; present their own evidence and witnesses; and have an advocate, interpreter, and/or witnesses at the meeting. If the Board of Education decides to transfer a student involuntarily, the district must send the student and their parent/guardian a written notice of its decision that includes the reasons for the decision, the facts to support the reasons, and whether the decision will be reviewed periodically and, if so, the review procedures. It’s important to note that in order to avoid bias and prejudice, no one from the student’s school can participate in the final transfer decision. The final decision must be made by school district personnel and/or staff from other school sites.[51]

The procedural due process requirements for involuntary transfers in California are a lot more expansive than the minimal general requirements set out in Buchanan. Fortunately, most states and school districts, like California, offer students due process rights before they can be transferred involuntarily to an alternative school and provide guidelines for schools and students to follow.

IV. Disparities in Student Discipline

Disparities in student discipline arise when students of specific demographic groups are subjected to particular forms of discipline at a greater rate than students in other demographic groups, and when different and harsher disciplinary actions are taken against students from a particular demographic group compared to students who belong to other demographic groups when they commit the same offenses.

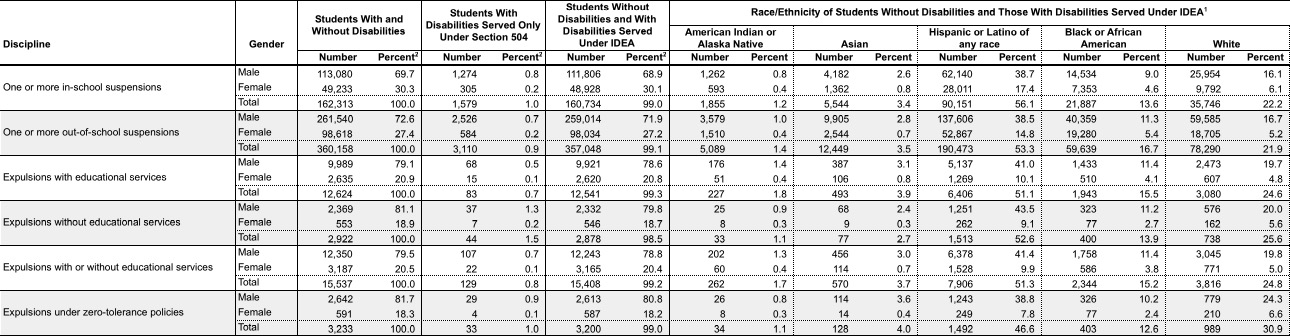

The U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights (“OCR”) conducts a Civil Rights Data Collection (“CRDC”) that collects data on key education and civil rights issues in public schools. Student discipline data collected in January 2014, demonstrated that African-American students were more than three times as likely to be suspended or expelled as their white classmates. African-American students only represented 15% of the students in the data collection, but they made up 35% of the students suspended once, 44% of the students suspended more than once, and 36% of students expelled.[52] OCR recognized that disparities in student discipline may be caused by different factors, but they noted that their research suggested that the significant disparities in their data was not explained by more frequent or more serious misbehavior by students of a particular demographic group, such as African-Americans.

These substantial and unexplained racial disparities in student discipline raised concerns that schools across the nation were engaging in racial discrimination that violated federal civil rights laws. Titles IV and VI protect students from discrimination based on race in connection with all programs and activities of a school, which includes programs and activities to ensure and maintain school safety and student discipline. Titles IV and VI requires schools to respond in a racially nondiscriminatory manner when responding to student misbehavior. These concerns gave rise to nationwide compliance reviews and complaint investigations by OCR focused on student discipline. These compliance reviews and investigations uncovered alarming findings nationwide for students based on race, gender, and disability status. California responded to the following data by reforming their student discipline policy to its current state.

a. Number and percentage of public school students with and without disabilities receiving disciplinary actions by gender and race/ethnicity, for California: School Year 2011-12

V. School Discipline Policy Proposals

The issue here is not whether students should ever be suspended, expelled, or involuntarily transferred, but rather whether the frequent use of exclusionary student discipline is effective in helping schools foster positive, healthy, and equitable climates that are conducive to teaching and learning. I think we can all agree that it does not. Below are my policy proposals to further reform student discipline policy in California and offer a model for all states and school districts to follow.

a. Summary of Policy Proposals for In-School Suspensions, Suspensions, and Expulsions

As proposed above, states should have only one category of suspendable and expellable offenses that are uniformed across the nation. Additionally, states should prohibit school districts’ use of in-school suspension, out of school suspension, and expulsion for the catchall category of willful defiance. This means that no students should be suspended or expelled for disrupting the classroom or defying school personnel authority. Instead, other interventions like the ones below should be used to address student misbehavior. Furthermore, all states should require school districts to try alternative measures like the ones below before they can suspend and/or expel a student. Limiting school officials’ discretion to suspend or expel a student for less serious offenses minimizes the risk of disparities in student discipline.

b. Prohibit the Use of Involuntary Transfers

In addition to the policy proposals for in-school suspension, suspension, and expulsions, I’m also proposing that we eliminate the use of involuntary transfers unless the students is transferred to an alternative school as a result of an expulsion or to help students in the juvenile detention system. According to Professor Derek Black, the education provided at alternative schools is generally different and qualitatively inferior to regular school. Professor Black notes that alternative schools have students from various grades in the same classroom, and that a single teacher may be responsible for teaching students all of the different subject areas. He further points out that alternative schools often times lack the resources to deliver consistent special education services to the students that are entitled to them. He goes on to quote a report stating that, “many alternative schools are no more than holding pens for children considered to be troublemakers.”[53] For all these reasons, I do not think that involuntarily transferring students to alternative schools serves the main goals of educating students in preparing them for higher education or the job market, encourage them to be active civic participants, and help them lead a full life.

c. Adopt and Implement Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports

Another policy proposal is that all states and school districts, like California and other states and school districts, adopt and implement Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (“PBIS”) and/or School-Wide Positive Behavior Intervention Support (“SWPBIS”). Districts like San Francisco Unified School District, San Jose Unified School District, Berkeley Unified School District, Napa Valley Unified School District, and Irvine Unified School District to name a few, have all implemented one if not all three of these methods.

PBIS is an approach that promotes positive student behaviors that focus on developing school-wide norm and expectations, trains teachers and staff on effective classroom management techniques and the use of positive reinforcement, and provides early, individualized and positive interventions for misconduct.

SWPBIS is when PBIS is applied at the school wide level to changes the systems and processes for student discipline for the entire school and/or district. The district wide change was important for those districts that wanted to address the disproportionate suspension and expulsion of African American and Latino students, as well as any other group of students that was or is disproportionately disciplined.

The underlying theme for both PBIS and SWPBIS is teaching behavioral expectations as part of the core curriculum like we do other core subjects. Both methods focus on preferred behaviors of students instead of telling students what not to do. School teams of administrators, classified staff, and regular or special education teachers attend extended training sessions provided by skilled and experienced trainers to teach this method and help the school come up with three to five behavioral expectations that are easy for students to remember such as: (1) respect yourself, respect others, and respect property; (2) be safe, be responsible, be respectful; or (3) respected relationships and respect responsibilities.[54] The SWPBIS team takes their proposed behavioral expectations back to the school to make sure that the other school staff agrees with the expectations. If the expectations are successfully received by the other school staff, then the SWPBIS team creates a matrix of what the behavioral expectations of students look like, sound like, and feel like in all the school areas. The matrix can have three to five positively stated examples for each classroom and non-classroom area. An example for the respecting property behavioral expectation above could be: on the bus, students must keep feet and hands where they belong, throw unwanted items in wastebasket, and keep food and drinks inside backpacks; in the cafeteria, students must place tray in designated areas after scraping leftovers into wastebaskets, wipe and clean table areas, and clean food spills off floor; in the restrooms, students must flush toilet after use, use two squirts of soap to wash hands, and throw paper towels in wastebaskets; in the playground, students must report any graffiti or broken equipment to the adult on duty, return playground equipment to proper area, and use equipment as it was designed; in the classroom, students must put belongings away when they enter the room, keep their workspace clean and organized, and use material and equipment for their intended purposes.[55] Again, the SWPBIS team would have to ensure that the other school staff agree and approve the matrix because behavioral expectations of students need to be consistent school wide.

The SWPBIS team would also work with teachers at the school site to create matrices for behavioral expectations for classroom routines such as entering and exiting the classroom, teacher instruction, group work, independent work, and transitions. The SWPBIS team and teachers decide on when and where to teach students the behavioral expectations. Most schools and districts that use this method take the first few days of school to teach students the behavioral expectations in each area.

The SWPBIS team also works on the office referral process. They determine what behaviors need to be addressed in the classroom and which behaviors constitute an automatic trip to the principal’s office. Another important thing that the SWPBIS team works on is determining ways for the school to recognize good student behavior. Most schools use specific verbal praise where teachers or school staff compliment and congratulate students verbally for good behavior. Schools also develop a “gotcha” program is a system for labeling appropriate behavior that often serves as prompts and reminders for school staff to remember to catch kids engaging in positive behavior instead of catching them when they are behaving inappropriately.

Research shows that PBIS is an effective method for responding to student discipline. PBIS has been shown to improve school climate, reduce disciplinary issues, improve academic engagement and achievement, decrease school arrests, improve attendance, and reduce the risk of future delinquency and drug use. Another approach that seems promising is restorative discipline, which is modeled after restorative justice interventions that focus on addressing the needs of the victims, offenders, and the school community, rather than focusing only on punishment of the offender.[56]

d. Adopt and Implement Restorative Justice Processes

States can offer restorative justice programs as one of many alternative methods for school districts to use before a school can use in-school suspension, out of school suspension, or expulsion. Restorative justice is a community building process that focuses on healing the relationships between the offenders, victims, other students, school staff, and even parents. Parties involved use restorative circles and conferences where they discuss the problem or misconduct and they find a solution and appropriate punishment together.

e. Adopt and Implement Peer Mediation Programs

States can also offer peer mediation programs as another alternative method for school districts to use before resorting to in-school suspension, out of school suspension, or expulsion. Peer mediation is a program that can be used before school, during recess or lunch, after school, or even during a class period for older students, where students are taught how to resolve disputes effectively. Students trained in mediation techniques help other students involved in a dispute reach a solution by working together and collaboratively in a group.

f. Professional Development for School Staff

States should also require school districts to provide annual training and professional development for school employees in the areas of trauma informed practices, behavior de-escalation support, and most important implicit bias and stereotype of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, sensitivity and cultural competency training. School personnel should be provided with cultural awareness training on working with a racially diverse student population and on the harmful effects of using or failing to address racial stereotypes and biases. If we provided teachers with this type of training, they will be better equipped to recognize cultural miscommunications and tell them apart from discipline issues. Non-biased student discipline is the key to eliminating the disparities that exist in student discipline for male students of color and students with disabilities.

g. Collect Data and Take Responsive Action

In addition to everything above, states should require school districts to collect and analyze student discipline data and to report the aggregated data to students, families, community, and stakeholders. The data collected should include the student’s race, gender, and any disability, the offense for the discipline referral, the referring school employee’s name, the resulting disciplinary action and any alternative methods used, and the name of the administrator that imposed the discipline.

Districts should commit to providing extra support and intervention to schools with significantly greater disproportionate suspensions and expulsions, and require principals to consult with their assistant superintendent or superintendent of schools to ensure that all alternative interventions have been exhausted and documented before the principal can suspend an African American or Latino student, or any other demographic group identified as disproportionately disciplined.

[1] Cal. Const. Art. IX, §5.

[2] Serrano v. Priest (Serrano I), 487 P.2d 1241, 1244 (Cal. 1971)

[3] Losen, D.J. and Skiba, R.J. (2011), Suspended Education: Urban Middle Schools in Crisis, Southern Poverty Law Center, Retrieved April 8, 2012 from http://civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/research/k-12-education/school-discipline/suspendededucation-urban-middle-schools-in-crisis. Skiba, R.J., & Rausch, M.K. (2006). Zero tolerance, suspension, and expulsion: Questions of equity and effectiveness. In C.M. Evertson, & C.S. Weinstein (Eds.), Handbook for Classroom Management: Research, Practice, and Contemporary Issues (pp. 1063-1089). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

[4] Cal. Ed. Code § 49001

[5] U.S. Const. Amend. XIV § 1

[6] 347 U.S. 497 (1954)

[7] 419 U.S. 565 (1975)

[8] 501 F.3d 577 (6th Cir. 2007)

[9] 294 F.2d 150 (5th Cir. 1961)

[10] 99 F.3d 1352, 1356 (6th Cir. 1996)

[11] Nevares v. San Marco Consol. Ind. Sch. Dist., 111 F.3d 25, 25-27 (5th Cir. 1997); C.B. v. Driscoll, 82 F.3d 383, 389 n.5 (11th Cir. 1996); Doe v. Bagan, 41 F.3d 571, 576 (10th Cir. 1994); Zamora v. Pomeroy, 639 F.2d 662, 669-670 (10th Cir. 1981)

[12] Maureen Carroll, Racialized Assumptions and Constitutional Harm: Claims of Injury Based on Public School Assignment, 83 Temp. L. Rev. 903,914 (2011)

[13] Jennings v. Wentzville R-IV Sch. Dist., 397 F.3d 1118, 1125 (8th Cir. 2005)

[14] Johnson v. Collins, 233 F. Supp. 2d 241, 248 (D.N.H. 2002); Carey ex rel. Carey v. Maine Sch. Admin. Dist. No. 17, 754 F. Supp. 906, 919 (D. Me. 1990); Bd. of Educ. of Monticello Cent. Sch. Dist. v. Comm’r of Educ., 91 N.Y.2d 133, 140-141 (1997); Mills v. Bd. of Educ. of D.C., 348 F. Supp. 866, 882 (D.D.C. 1972)

[15] Dillon v. Pulaski Cnty. Special Sch. Dist., 594 F.2d 699 (8th Cir. 1979); Carey ex rel. Carey v. Maine Sch. Admin. Dist. No. 17, 754 F. Supp. 906; DeJesus v. Penberthy, 344 F. Supp. 70, 76 (D. Conn. 1972); Colquitt v. Rich Twp. High Sch. Dist. No. 227, 699 N.E.2d 1109, 1115-1116 (Ill. Ct. App. 1998); In re E.J.W., 632 N.W.2d 775 (Minn. Ct. App. 2001)

[16] Newsome v. Batavia Local Sch. Dist., 842 F.2d 920 (6th Cir. 1988); Dornes v. Lindsey, 18 F. Supp. 2d 1086 (C.D. Cal. 1998)

[17] Osteen v. Henley, 13 F.2d 221, 225 (7th Cir. 1993); Newsome v. Batavia Local Sch. Dist., 842 F.2d at 925-926 (6th Cir. 1988); Gorman v. Univ. of R.I., 837 F.2d 7, 16 (1st Cir. 1988)

[18] Bd. of Educ. of Monticello Cent. Sch. Dist. v. Comm’r of Educ., 91 N.Y.2d 133, 139 (1997); Riggan v. Midland Indep. Sch. Dist., 86 F. Supp. 2d 647 (W.D. Tex. 2000)

[19] Cal. Ed. Code § 48915

[20] California Department of Education, Administrator Recommendation of Expulsion Matrix (June 7, 2016), http://www.cde.ca.gov/ls/ss/se/expulsionrecomm.asp

[21] Cal. Ed. Code § 48903

[22] Cal. Ed. Code § 48900.5

[23] Cal. Ed. Code § 48900.5

[24] American Civil Liberties Union of Northern California, California Enacts First-in-the-Nation Law to Eliminate Student Suspensions for Minor Misbehavior (September 27, 2014), https://www.aclunc.org/news/california-enacts-first-nation-law-eliminate-student-suspensions-minor-misbehavior

[25] Cal. Ed. Code § 48911 (b)

[26] Cal. Ed. Code § 48911 (c)

[27] Cal. Ed. Code § 48911 (d)

[28] Cal. Ed. Code § 48911 (e)

[29] Cal. Ed. Code § 48911.1 (a)

[30] Cal. Ed. Code § 48911.1 (b)

[31] Cal. Ed. Code § 48911.1 (c)

[32] Cal. Ed. Code § 48911.1 (d)

[33] Cal. Ed. Code § 48915 (b) and (e)

[34] Cal. Ed. Code § 48916 (b)

[35] Cal. Ed. Code § 48916 (c)

[36] Cal. Ed. Code § 48918 (a) (1)

[37] Cal. Ed. Code § 48918 (a) (2) and (3)

[38] Cal. Ed. Code § 48918 (b)

[39] Cal. Ed. Code § 48918 (c) (1)

[40] Cal. Ed. Code § 48918 (c) (1) and (2)

[41] Please see Cal. Ed. Code § 48918 (c) (3) and Cal. Ed. Code § 48918 (d)

[42] Cal. Ed. Code § 48918 (h) (1)

[43] Cal. Ed. Code § 48918 (f) (2)

[44] Cal. Ed. Code § 48918 (g) and (k) (2)

[45] Cal. Ed. Code § 48919

[46] Cal. Ed. Code § 48919.5

[47] Cal. Ed. Code § 48921

[48] Cal. Ed. Code § 48922

[49] Cal. Ed. Code § 48923

[50] Cal. Ed. Code § 48924

[51] Cal. Ed. Code § 48432.5

[52] U.S. Department of Education, Office of Civil Rights, Civil Rights Data Collection, Wide-Ranging Education Access and Equity Data Collected from our Nation’s Public Schools, http://ocrdata.ed.gov

[53] Advancement Project, Opportunities Suspended: The Devastating Consequences of Zero-Tolerance and School Discipline 12 (2000)

[54] OSEP Technical Assistance Program, Positive Behavioral Interventions & Supports, SWPBIS for Beginners

[55] OSEP Technical Assistance Program, Positive Behavioral Interventions & Supports, SWPBIS for Beginners

[56] Katayoon Majd, Students of the Mass Incarceration Nation, 54 How. L.J. 343 (2011)

You have to be 100% sure of the quality of your product to give a money-back guarantee. This describes us perfectly. Make sure that this guarantee is totally transparent.

Read moreEach paper is composed from scratch, according to your instructions. It is then checked by our plagiarism-detection software. There is no gap where plagiarism could squeeze in.

Read moreThanks to our free revisions, there is no way for you to be unsatisfied. We will work on your paper until you are completely happy with the result.

Read moreYour email is safe, as we store it according to international data protection rules. Your bank details are secure, as we use only reliable payment systems.

Read moreBy sending us your money, you buy the service we provide. Check out our terms and conditions if you prefer business talks to be laid out in official language.

Read more