Table of Contents

Impact on Human Population and the Environment

Monitoring and Evaluating Pollution

Policy and Guidelines Australia

In 2006, the Probo Koala offloaded approximately 500 tonnes of toxic waste in Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire (Ognibene, 2007). The Panamanian registered ship was commissioned by the multinational corporation Trafigura Beheer BV who operates in the trade of oil and commodities. The company’s initial attempt of disposal occurred at a specialised firm in Amsterdam, APS, in July 2006. However, once the offloading begun it was discovered that the toxic waste was unusual and different to what was initially expected by APS. In order to account for the highly toxic waste and increased disposal measures APS requested an increase in the treatment cost. Unfortunately, the Probo Koala declined and reloaded the waste product, without any subsequent cleaning, and proceeded on to find a company willing to treat the waste cheaply. In Abidjan, the company ‘Tommy’ was contracted to dispose of the waste. The company who was inexperienced in waste disposal and who was incorrectly licensed was involved in the dumping of this toxic waste at several sites around in City, including open-air sites and waterways (Adriaanse, 2010). The waste product was mostly made up of low-grade oil that had been cleaned with sodium hydroxide and lead to horrific disturbances to the local community such as foul odours, breathing difficulties, vomiting, nausea and even death (Adriaanse, 2010).

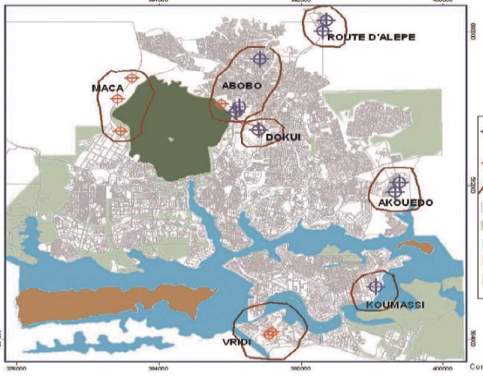

Figure 1 Diagram illustrating the dumping sites of the Toxic Waste in Abidjan (Koné et al., 2011).

The low-grade gasoline being transported, known as coker naphtha, can have high levels of Nitrogen and up to 20 times more sulphur. By completing caustic cleaning the product can be sold however leaves behind by-products such as mercaptans, phenols and hydrogen sulphide (Milmo, 2010).

The effects of Hydrogen sulphide on Humans is dependent on the exposure. Lower concentrations of 50ppm can lead to irritation of the eyes and respiratory tract however higher concentrations such as above 600ppm for 30 minutes can be fatal. Similarly, Methyl Mercaptan is highly toxic to both humans and aquatic species with a LC50 (lethal concentration resulting in 50% fatalities) of 675ppm within 4 hours of exposure. The presence of these substances in the waste can explain the response of the population within proximity to the dumping sites.

It is estimated that 108,000 people were affected with 69 of those being hospitalized and 15 deaths as a result of the dumping (Bowers, 2009). Via a public health survey Kone et Al (2009) assessed the socio-economic impact in the aftermath of the dumping. Sampling 5 sites it was found that at least 1 person per household within the vicinity of the site showed signed of illness. This environmental disaster also had an economic disadvantage to the households as 1/3 had to pay for medical assistance, which cost twice the minimum wage, as the free clinics were at high capacity (Koné et al., 2011). Similarly, 25% of the households had to relocate from their homes which caused an economic burden on the family who were forced to take loans for the move (Koné et al., 2011).

Due to the location of the dumping sites the environmental impacts affected the air, land and waterways. It is estimated that approximately 7.75 tonnes of Hydrogen Sulphide was discarded per dumping site and subsequent air modelling demonstrated a 3.5km radius of concentrations associated with high risk (Gallagher, 2012). Similarly, there was an estimated 7.75 tonnes of mercaptans deposited per site which showed a 2.3km radius of excessive concentrations (Gallagher, 2012). This pollution had the potential to enter the water supply and also the food chain via soil infiltration and could still be affecting the community Today 11 years on, however with the lack of reporting the true state of the pollution is left unknown (2016).

Due to the nature of the toxic waste and the dumping method the risk assessment is high as there are many exposure pathways. This dumping can lead to air pollution, soil pollution and water pollution. As many were open-air sites the odour was a predominant concern to the community and this can still be an issue Today after heavy rain. From the dumping site the toxic waste could have two methods of exposure; via groundwater and via transport through the air. From the site leaching can occur and can be transported via groundwater. Once below the water table this can spread to other water sources and can cause exposure to humans and plants. Similarly, via volatilization contaminants from the site can be released into the air where they can be transported and inhaled. Depending on the prevailing wind direction these volatile substances could have spread to any of the neighbouring communities. As the waste is suggested to contain Hydrogen Sulphide and Mercaptans this inhalation could have been, as was, detrimental to people’s health. In order to minimise the risk, nearby communities should have been provided masks and evacuated from near the sites. If there were adequate resources plume models, as seen by Gallagher (2012), could have been used to determine the area’s most at risk. Exposure assessment could also identify those at risk by establishing their points and duration of exposure to the potentially harmful substances.

Similarly, as it can leach from the site there would have been presence of toxins in the soil around the sites. These toxins, once entering the groundwater, could then have entered the waterways and hindered drinking water and agriculture.

One of the main issues was that not only was it unsure what Trafigura had actually dumped but it was unknown if other dumping of toxic materials had occurred previously in the sites. When beginning the remediation, it was found that there were variations in the heavy metals and hydrocarbons found that what is usually expected from coker naptha.

To fully assess the implications of this dumping testing including soil, sediment, water and air sampling methods over an extended period.

The response and control measures for the Cote d’Ivoire disaster are intricate and continuing 11 years later. The biggest issue faced by the response team dedicated to cleaning up the waste is that the shipping company, Trafigura, has still not published the actual chemical composition of the waste, making it difficult and dangerous to clean and dispose of. The initial clean-up of the pollutants took many years with farmers and landowners claiming to still smell the toxic waste after heavy rain.

Abidjan never had the facilities to properly dispose of this toxic waste, so infrastructure and treatment facilities have had to be built in the wake of this disaster. Another issue was that the sites were spread across 18 different sites all requiring remediation. There was also a great fear of poisoning the food and water supply of Abidjan too, with organochlorines being detected in the waste (AIGN, 2012). Organochlorines can pass through the food chain and be ingested in many ways. The government put a temporary ban on all fishing, farming and commercial activities near affected sites and ordered crops and livestock to be destroyed.

The official physical clean-up of the was waste done by a French company by the name of Tredi and begun in 2006 approximately 1 month after the incident. The total estimate of waste and polluted soil was said to be approximately 2,500 tonnes, spread across 18 dumping sites, each with different considerations in land, location and affected environment. As de-contamination was underway was found that their estimation for the amount of waste was underestimated and they submitted a proposal for a new contract, however an agreement was never reached.

Burgeap took over the treatment and recommended biodegradation treatment for the remaining affected areas. On April 4th, 2008 it was agreed that limited further biodegradation treatment was needed and the final payment for the treatment was made. A four-year monitoring plan was put into place to track the progress and success of the project.

Following visits by a UN reporter on toxic waste and human rights in August 2008, it was deemed that the sites continued to pose a risk to health and that sufficient control of the contamination had not been conducted (AIGN, 2012). Later visits by Amnesty International in February 2009 confirmed these reports, with bags of contaminated waste being found stacked in piles still located near houses and major roads.

Since it’s official end in October 2006, there has been no ongoing health assistance and monitoring available for anyone in the area. This poses great concerns for long term health problems as they cannot be linked to this disaster by anecdotal evidence. Combining this with the fact that the exact contents of the waste was never released, it’s of great concern that the affected Ivorians may suffer from further illness in times to come.

The outcomes of this situation have been catastrophic and widespread. With over 30,000 people injured and 15 confirmed dead the human toll has been massive. Combining this with approximately 500 households being rendered uninhabitable, and over 109.5 hectares of farmland being destroyed the overall impact on the life of people in Abidjan has been severe. With the clean up taking many years and Trafigura never releasing the contents of the waste, the full outcomes of this may never be fully realised.

The knowledge gained from this situation has been mostly legislative. The ability of Trafigura to find loopholes in the existing legislation to illegally dump this waste has since been rectified and international treaties, such as the Basel Convention, have been revised with harsher standards on chemicals being implemented as well as more rigorous testing on potentially hazardous waste being mandatory.

As Africa is a developing country there is no emphasis on pollution control as the African government lack the funds, technology and expertise to fix these problems. Environmental health risk factors are overshadowed by other risks like malnutrition, HIV, tuberculosis and malaria. Despite the implemented policies such as the Basel Convention in a country where they are hindered by economics it can be a lucrative solution to ignore not only the policy but also the risks in a black trade market as seen by the Probo Koala disaster (Lambrechts and Hector, 2016).

It wasn’t until the 23rd of August, approximately 4 days after the dumping, that medical professionals were made aware of a potentially devastating chemical dump that had occurred. Once it was realised the extent of the disaster, a total of 32 medical centres and 20 mobile medical units were dispatched to attempt to provide free services to accommodate for the affected people. International assistance was also received, with the UN, Red Cross and USA all offering medical experts in the field and appropriate medicines and treatment services. The United Nations also supplied experts from its Disaster Assessment and Coordination team that were experts on environmental and hazardous waste.

Due to the country’s economic status to provide the necessary services to the impacted communities several lawsuits were filed. Despite the company not accepting any liability, the Ivory Coast Government was awarded an 140 million pounds (Adriaanse, 2010). A Civil Lawsuit was also successful and resulted in the participants being awarded 30 million pounds to compensate for the implications.

Côte d’Ivoire signed the Bamako Convention in 1991, ratified in 1994, and registered with the United Nations in 2000 (Union, 2016). This policy detailed the banning of the import into Africa and the control and management of hazardous wastes within Africa. However, without proper enforcement and regulations it is unsure how effective this will be (Alam et al, 2012).

The state policies in Victoria create strict guidelines to follow for the management of Industrial waste resources. These guidelines are detailed and enforced by the Victorian legal system.

Industrial wastes are classified into 3 categories, A, B and C:

Table 1 Classification of Waste Products

| Category A includes waste which is waste that qualifies as a dangerous goods | Class 1 (Explosive) |

| Class 2.3 (Toxic Gas) when in contact with air or water; | |

| Class 4.1 (Flammable solid); | |

| Class 4.2 (Spontaneously combustible); | |

| Class 4.3 (Dangerous when wet); | |

| Class 5.1 (Oxidising); | |

| Class 5.2 (Organic Peroxide); | |

| Class 6.1 (Toxic); | |

| Class 6.2 (Infectious); | |

| Class 8 (Corrosive); |

Industrial wastes also include other waste that exceeds contaminant concentration or leachable concentration that is specified in the industrial waste, soil, or waste water thresholds for category A. Category B and C have subsequently lower concentration thresholds (Regulations, 2009).

A series of steps must also be followed for industrial waste management and disposal to be completed to the standard required by the authoritative parties. These are outlined below in Table 2.

Table 2 Mandatory Requirements for the Handling of Industrial Waste Products Australia (Regulations, 2009).

| Classification | The waste must be classified by an authority into a relevant waste category. |

| Permit | Transport of industrial waste must be carried out by a permit holder that has a vehicle fit to transport the prescribed industrial waste. No other wastes except those listed on the permit may be transported under the permit. |

| Licensing | Transport of the prescribed waste cannot occur unless the receiving premises is licensed to receive prescribed waste. |

| Vessel | Containers supplied to store the prescribed industrial waste during transport must not be allowed to escape, spill, or leak. The producer of such containers will be fined if they have been found to leak. |

| Certification | Transport certificates must be completed before the waste is transported, and after it is received. The receiver must then notify the authority within 7 days of receiving the waste. |

| Records | Records of these receipts must be retained by the waste producer, the waste transporter, and the waste receiver for 24 months from the date on which the waste was transported |

Transport Information must also be supplied by the industrial waste producer according to the Environment Protection (Industrial Waste Resource) Regulations 2009. These include 20 details such as their Hazard category, Physical Nature, Origin of Waste and Amount of Waste. With these details it can be ensured that the waste can be adequately treated to ensure there are no implications to individuals and the environment. They also must provide details of emergency contact details, who is receiving the waste and how they intend to treat it.

The waste offloaded is still unproperly classified by Trafigura, who refuses to disclose the exact nature of the toxic waste (Fraser, 2008). In Victoria, extensive details of the waste would have been provided before unloading of the toxic waste, and the company receiving the waste would have required license and proven to be able to process the prescribed waste before being allowed to accept it (Regulations, 2009). Treatment of waste to obtain a license is subject to RR&D(Research, Development and Demonstration) approval, where the company must provide the research to show and also demonstrate how it would effectively neutralise the waste (EPA, 2016). The effectiveness of laws comes down to regulation and the authorities. To compare our legal system and enforcement with Côte d’Ivoire’s, it lacks the further comparison of International law that failed Côte d’Ivoire to the proper recompense it deserved from Trafigura. Multinational companies choose those countries with the weakest laws and enforcement to deal with toxic wastes, that would otherwise be costly to neutralise via the proper means. The next step is to ensure these companies can be liable for dumping their toxic wastes to the less developed and economically capable countries.

There have been many similar environmental disasters that have occurred around the world including oil spills and incorrect disposal of toxic waste. There have also been seemingly innocent products that have had direr consequences to the environmental that occurred many years after its introduction. From the Love Canal in America and the use of CFC’s in industry environmentalists and governments have seen devastation and enforced changes to ensure it doesn’t happen again in the future.

A similar environmental disaster occurred in the 1970’s and had a dramatic influence in America’s environmental policy. Hooker Chemical Company utilized Love Canal as a dumping site for toxic chemicals for approximately 10 years before selling the property for $1 to the Niagara School Board (Hevesi, 1988). Driven by economic group the local council began developing the area into housing developments, parks and schools for low-income families, unaware of the potential dangers below the surface. After fluctuations in the weather chemicals were brought to the surface where residents complained of strong odours and thick and dark liquids arising from the canal. In 1978 it was declared an emergency by the State Health Commissioner and residents were evacuated with an influence on young children and pregnant women (Hevesi, 1988). From the exposure to the toxic chemicals many of the residents went on to have leukemia, fertility issues and some were found to have chromosomal abnormalities (Hevesi, 1988). Similarly, in this case the company was found to be guilty and paid for compensation to the residents and the clean-up to the site. It is believed, however, that this disaster was the beginning of environmental activism and lead to many changes within the Environmental Policies enforced as individuals began to see the power they had to bring those to justice (Ferguson, 2017).

Chlorofluorocarbons (CFC’s) were once widely used in a range of different manufacturing applications including the production of aerosols, packaging and in refrigeration. As there were so many applications for CFC’s there was a dramatic increase in its production whereby in 1974 approximately 1 million tonnes were being produced annually worldwide (Badr et al., 1990). It was first suggested by Molina and Rowland in 1974 that these CFC’s when released into the atmosphere have adverse effects in particular on the ozone layer; This can now be explained by the production of chlorine radicals when the compound is broken down via ultra-violet radiation (Badr et al., 1990). CFC’s were classified as an ozone-depleting substance and it became essential to reduce their production to reduce future destruction. The Montreal Protocol was established in order to reduce and eliminate the production of ozone-depleting substances and had since been adopted by 196 countries and the EU (Gonzalez et al., 2015). Through its amendments over the years to include further compounds and its methods of financial assistance and public awareness the protocol has continued to be arguably one of the most successful. This response has shown that when working as a collective the effects of an environmental disaster can not only be resolved but can also ensure it does not happen in the future and gives greater awareness.

The events from the Probo Koala can be considered nothing but disastrous as it has had a profound effect on the community and the environment. Most concerning is the disregard of the company to initially accept responsibility and understand the impact that they had. As individuals lost their lives and families were relocated from their homes the impact can still be felt today by those effected. In a country with economic difficulties it is still reassuring to see the individuals affected were provided the healthcare they required through free medical clinics. Despite a drawn-out proceeding, the country saw justice through the settlement they received for the remediation of the land. It is now hoped that this will be adequately remediated and will prevent any further damage to the community and environment. From other case studies around the world it can be seen that we learn from these disasters and fight to ensure these cannot be repeated in the future without consequences.

(2016). Ten Years on, the Survivors of Illegal Toxic Waste dumping in Cote d'Ivoire remain in the Dark (Coventry).

Adriaanse, C. (2010). Tragifura convicted over toxic waste. Chemistry & Industry, 6-6.

Alam, S., Bhuiyan, J. H., Chowdhury, T. M. & Techera, E. J. 2012. Routledge Handbook Of International Environmental Law, Routledge.

Amnesty International & Greenpeace Amsterdam. (2012). The Toxic Truth. [Web] accessed 17 May 2017, available from < https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/AFR31/002/2012/en/>

Badr, O., Probert, S.D., amp, Amp, Apos, and Callaghan, P.W. (1990). Chlorofluorocarbons and the environment: Scientific, economic, social and political issues. Applied Energy 37, 247-327.

Bowers, M. (2009). No longer secret: report into 'potentially fatal' waste [Edition 3] (London (UK)), pp. 21.

Epa 2016. Research, Development And Demonstration (Rd&D) Approval.

Ferguson, C. (2017). Love Canal: A Toxic History from Colonial Times to the Present. By Richard S. Newman. Environmental History.

Fraser, L. 2008. The Probo Koala Inquiry: Second Interim Report.

Gallagher, D.R. (2012). Environmental leadership: A reference handbook (Sage Publications).

Gonzalez, M., Taddonio, K., and Sherman, N. (2015). The Montreal Protocol: how today’s successes offer a pathway to the future. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences 5, 122-129.

Hevesi, D. (1988). The long history of a toxic-waste nightmare. (Love Canal), pp. B4.

Koné, B., Tiembré, I., Dongo, K., Tanner, M., Zinsstag, J., and Cissé, G. (2011). Socio-economic impact at the household level of the health consequences of toxic waste discharge in Abidjan in 2006. Bull Soc Pathol Exot 104, 14-19.

Lambrechts, D., and Hector, M. (2016). Environmental Organised Crime: The Dirty Business of Hazardous Waste Disposal and Limited State Capacity in Africa. Politikon, 1-18.

Milmo, C. (2010). Take toxic waste. Add caustic soda. Worry about the danger later (London (UK)), pp. 8.

Ognibene, L. (2007). Dumping of Toxic Waste in Côte d'Ivoire: The International Framework. Environmental Policy and Law 37, 31-33.

Regulations, E. P. 2009. Environment Protection (Industrial Waste Resource) Regulations 2009 S.R. No. 77/2009.

Union, A. 2016. List Of Countries Which Have Signed, Ratified/Acceded To The Bamako Convention On The Ban Of The Import Into Africa And The Control Of Transboundary Movement And Management Of Hazardous Wastes Within Africa. Ethiopia.

You have to be 100% sure of the quality of your product to give a money-back guarantee. This describes us perfectly. Make sure that this guarantee is totally transparent.

Read moreEach paper is composed from scratch, according to your instructions. It is then checked by our plagiarism-detection software. There is no gap where plagiarism could squeeze in.

Read moreThanks to our free revisions, there is no way for you to be unsatisfied. We will work on your paper until you are completely happy with the result.

Read moreYour email is safe, as we store it according to international data protection rules. Your bank details are secure, as we use only reliable payment systems.

Read moreBy sending us your money, you buy the service we provide. Check out our terms and conditions if you prefer business talks to be laid out in official language.

Read more