Table of Contents

1. Overview of Knowledge Management…………………………………..

1.1 Drivers of Adopting Knowledge Management Strategy…………………….

1.2 Benefits of Knowledge Management…………………………………

2. Case Study………………………………………………………

2.1 Accenture KM strategy…………………………………………..

2.2 Stakeholder Analysis…………………………………………….

3. Change Assessment………………………………………………..

3.1 Organization Diagnosis Model

3.2 Change Assessment of Accenture KM Strategy………………………….

4. Evaluation……………………………………………………….

4.1 Challenges of Accenture KM Strategy………………………………..

4.2 Recommendations

5. Conclusion

References

Nowadays, many strategies have been explored by organizations around the world to attain sustainable competitive advantage in today’s highly competitive environment. One of the strategies widely considered, especially in the era of knowledge economy, is to manage knowledge. The importance of knowledge as a valuable resource has been realized by many organizations as they are starting to adopt Knowledge Management (KM) strategy to capture their employee’s knowledge and facilitate knowledge sharing (Earl, 2001; Wang et al., 2014).

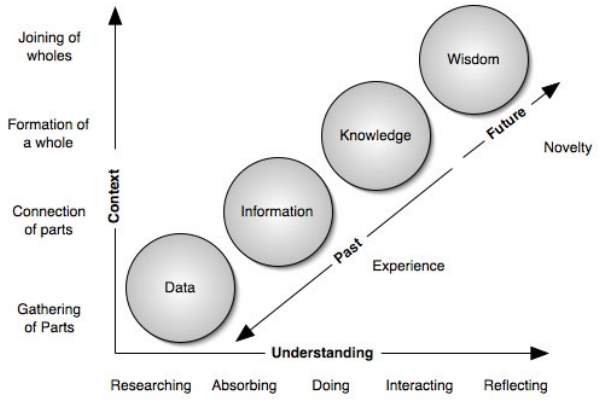

In understanding KM, first we must understand knowledge, as it is the central concept behind knowledge management and is often confused with information and data as these three terms are often used interchangeably. However, there is a clear difference between data, information, and knowledge. In fact, the relationship between these terms is hierarchical as seen in figure 1. Data is defined as physical, external substance, and resource which originate from a range of different sources. Whilst, information is processed data that is useful for its intended recipient (Boisot and Canals, 2004; Hey, 2004). On the other hand, Alavi and Leidner (1999, p. 5) defined knowledge as “justified personal belief that increases an individual’s capacity to take effective action”. It is possessed in the minds of people, and knowledgeable people are able to create and expand possibilities obtained from their skills, and previous experience (Grover and Davenport, 2001).

Figure 1, Data, Information, Knowledge, and Wisdom (DIKW) Hierarchy. Source: (Hey, 2004)

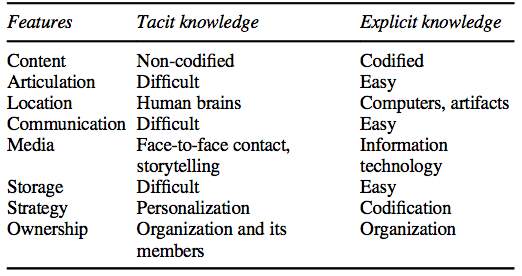

The idea behind KM is for organizations to enhance their ability to learn faster than their competitors by utilizing knowledge as a resource. It focuses on aligning the organization strategy and knowledge capital by supporting the creation, transfer, sharing of knowledge within and outside the organization (Shannak and Masa’deh, 2012; Perez-Soltero et al., 2015). There are mainly two types of knowledge that are utilized in KM, namely tacit and explicit knowledge. Tacit knowledge is developed based on an individual’s experiences and embedded in the individual’s mind. It is difficult to document and transfer. On the contrary, explicit knowledge can be easily documented and transferred. Some of the explicit knowledge are developed from tacit knowledge (Roberts, 2004). A more comprehensive view on both knowledge types can be seen in figure 2. Jasimuddin and Zhang (2014) suggest two strategies to manage knowledge based on these two knowledge types, namely the personalization strategy and the codification strategy. The personalization strategy focuses on the process to store and transfer tacit knowledge using mainly direct interaction. Whilst, the codification strategy addresses the explicit knowledge to enable it to be easily available and accessible through computer or other organization interfaces.

Figure 2, Features of tacit and explicit knowledge. Source:(Jasimuddin and Zhang, 2014)

Literatures have suggested that Information Technology (IT) can play an important role in managing the knowledge resources and many organizations are investing in IT to develop a Knowledge Management System (KMS) to support various aspects of its knowledge management activities (Alavi and Leidner, 2001; Choi et al., 2010). Several studies (e.g. Choi et al., 2010; Pérez-López and Alegre, 2012) have indicated that KM could leverage IT infrastructure to store knowledge, provide organization members with a quick and effective access to information, and support collaboration through virtual discussions, and facilitate the standardization and automation of certain tasks. However, IT itself is only an enabler and needs to be complemented by other factors such as knowledge-sharing culture and leadership (Kuo and Lee, 2011).

Organization’s current core competencies could become rapidly irrelevant in today’s rapidly changing business environment. If an organization is not able to adapt to the environment, it might lose its competitive advantage. Therefore, forcing organizations to look at their resources and creating their dynamic capabilities. Dynamic capabilities involve the generation of new best practices and updating it continuously to allow an organization to react and adapt to the change in environment (Cepeda and Vera, 2007). Many organizations are considering KM strategy to attain dynamic capabilities. In this regard, KM facilitates organization to flexibly manage and utilize knowledge from within and outside the organization. Thus, enabling an organization to have dynamic capabilities (Alegre et al., 2013).

Apart from dynamic capabilities, adoption of knowledge management strategy is mainly driven by the Knowledge-based view of the firm, especially in the era of knowledge economy. This view suggests that knowledge is an important asset that has the potential to provide sustainable competitive advantage for an organization. Different perspectives of knowledge indicate that by managing knowledge, organizations are able to know, understand, and apply the right information and know-how to build and improve their core competencies. Furthermore, tacit knowledge within an organization is specific and unique, making it hard for competitors to imitate. Hence, allowing the organization to achieve sustainable competitive advantage (Alavi and Leidner, 2001; Zyngier and Venkitachalam, 2011).

Many benefits of adopting knowledge management strategy have been identified in the literature (e.g. Whelan and Carcary, 2011; Yahyapour et al., 2015) with most of it point mainly to three main benefits, namely, improving organization performance, knowledge retention, and improved and efficient human capital management.

Many organizations adopt KM strategy because it allows them to sustain its competitive advantage over competitors. KM initiative improves organization capabilities in planning their business strategies and enables them to create innovative products and solutions by providing them with critical information and knowledge about the business environment (Yahyapour et al., 2015). A study by Inkinen et al. (2015) in Finland suggests that organizations that utilize knowledge as main resources are improving their efficiency in the process of strategic planning, implementation and creating innovations. Additionally, adopting KM initiative combined with business process capabilities allow organizations to be agile and adaptive to the changing market, enabling them to achieve positive growth (Inkinen, 2016).

KM initiative enables organizations to retain their knowledge. KM views that individual employee knowledge is an important organization asset, implying that when employees leave the organization whether through moving, redundancies, or retirement, causes the organization to lose important knowledge because many of the knowledge is tacit knowledge which is difficult to imitate, such as the employee experience and know-how. This makes it critical for organizations to retain knowledge. This is because KM created an environment to stimulate employees to create new knowledge, share their knowledge, and collaborate with each other (Du Plessis, 2005; Whelan and Carcary, 2011). Therefore, allowing the knowledge to be stored as a collective organization knowledge and reused for future purposes (Zyngier and Burstein, 2012).

Currently, organizations are viewing its employees as their capital rather than resources. Many organizations are investing in training and learning their employees. KM combined with effective talent management could facilitate the alignment between individual learning of the employee and organization strategy. Moreover, it could provide employees with the latest knowledge relevant to their respective job, thereby improving their competencies, better decision-making, adapting capability to the changing business environment (Whelan and Carcary, 2011). Effective KM requires the employees to contribute and collaborate with each other. Hence, allowing it generate knowledge network across organization hierarchy, improved communication, and increase team performance. Subsequently, enabling it to be effectively transferred across employees which improve their learning and expertise. Collectively, this contributes to the overall organization performance in efficiently managing their human capital (Yahyapour et al., 2015).

The main source of information in this paper is a case study based on the paper “The shortcomings of a standardized global knowledge management system: the case study of Accenture” by Yongsun Paik and David Y. Choi in the year 2005 (Paik and Choi, 2005). Accenture is a leading global consulting company, with approximately 384,000 employees operating across 55 countries. Its net revenue reached $32.9 billion in the year 2016 (Accenture, 2017). It is considered as one of the KM leaders in the industry, investing in gathering its consultant knowledge and past experiences to achieve competitive advantage, spending more than $500 million on IT and people to support its KM strategy starting in the early 1990s. The data were collected in 2002 using in-depth personal interviews of 18 KM staff members and consultants working at Accenture across different countries. Among the themes asked to the interviewees are Accenture KM strategies, and organization structure and culture.

In implementing its KM strategy, Accenture developed a computerized system called ‘Knowledge Exchange (KX)’ that could be accessed using Lotus Notes and the internet aimed at storing internal knowledge within the company. It stores approximately 7,000 databases managed by 500 KM staff members globally with 150 knowledge managers focused on synthesizing, repackaging, and organizing the content. KX has been the most important tool to capture and transfer knowledge among the employees depicted by most consultants use it to search for past experiences, best practices, and market research to apply similar strategy and methodology for new projects. This process has helped the consultants to improve their project planning, minimize risk, and improve client deliverables quality.

However, all stories have its challenges. Despite all the interviewees agreed that KX has really helped them in their work, Accenture was unable to fully align its KM strategy across its global structure. It fails to fully understand the complexities of KM in a global context. Although the top management has tried to enforce knowledge submission by making it mandatory for consultants to submit knowledge, the findings suggested that the levels of consultants’ participation are uneven with its East Asia organizations participation is very low compared to other regions. It also found high inconsistencies in the knowledge submitted to the KX in East Asia region. Among others, the findings also suggested that there is a lack of appreciation of regional knowledge, inadequate support and insufficient allowances for local offices.

Implementation of a change strategy can have impacts on a lot of people within and outside of the organizations. Therefore, it is important to identify the stakeholders involved in the change to identify those who is affected by decisions or actions and can influence the change results (Reed et al., 2009).

The process of identifying stakeholders is achieved through stakeholder analysis. It is the process to identify and categorize the stakeholders involved, then analyse their interests, interrelations, and how they can influence the change implementation in order to better communicate, involve and manage the stakeholders (Yang et al., 2011).

There are various models and tools that can be used to conduct stakeholder analysis. This paper will use the CASOLO checklist to analyse the stakeholders involved in the case study of Accenture KX strategy because it provided a framework to categorize the stakeholders in order to better understand their involvement in a change initiative (Duncombe, 2017a).

The Clients is the people who received immediate benefits from the change initiative, in this case, the consultants and project managers are the main beneficiaries of the initiative as they will be able to perform their work better through access to past experiences and project strategy. Additionally, Accenture’s clients are the secondary client of the KX strategy because they can receive an improved deliverables quality performed by the consultants.

The Actors is the people that will perform activities of the change initiative. The consultants are also the actors in this case study because Accenture KX strategy is aimed at collecting past experiences and its consultants’ knowledge, hence it requires them to create knowledge documents based on project involvement and submit it to KX.

The Sponsor of Accenture KX strategy is the top management of Accenture. They are the ones who initiate, invest, and support the change initiative in the hope of improving organization performance and achieving competitive advantage for the company.

The Owner in this case study is the knowledge managers and KM staff members. They are the people who administer the KX databases. The submitted knowledge by consultants will be reviewed, repackaged, and organized by the knowledge managers with other KM staff members responsible for other activities associated with managing the KX.

The Legitimisers for this change effort is the consultants who tend to protect the existing norms and values. The consultants are mainly affected by KX because they already have their own way of doing their job and KX will promote a change in how they do their job. In addition, Accenture KX strategy also promotes a change of culture in terms of more collaboration between the consultants.

The Opinion Leaders could not be identified in this case study due to limited information available.

Currently, “the complexity, unpredictability, and instability of environmental change” has resulted in the need for organizations to carry out rapid and radical change to remain competitive (Worley and Lawler, 2010, p. 194). This required organization to conduct organizational diagnosis to plan appropriate strategies to implement change initiative. Therefore, it has become important for organizations to diagnose the problems, identify the current performance, and assess its readiness for change to determine appropriate change interventions (McFillen et al., 2013).

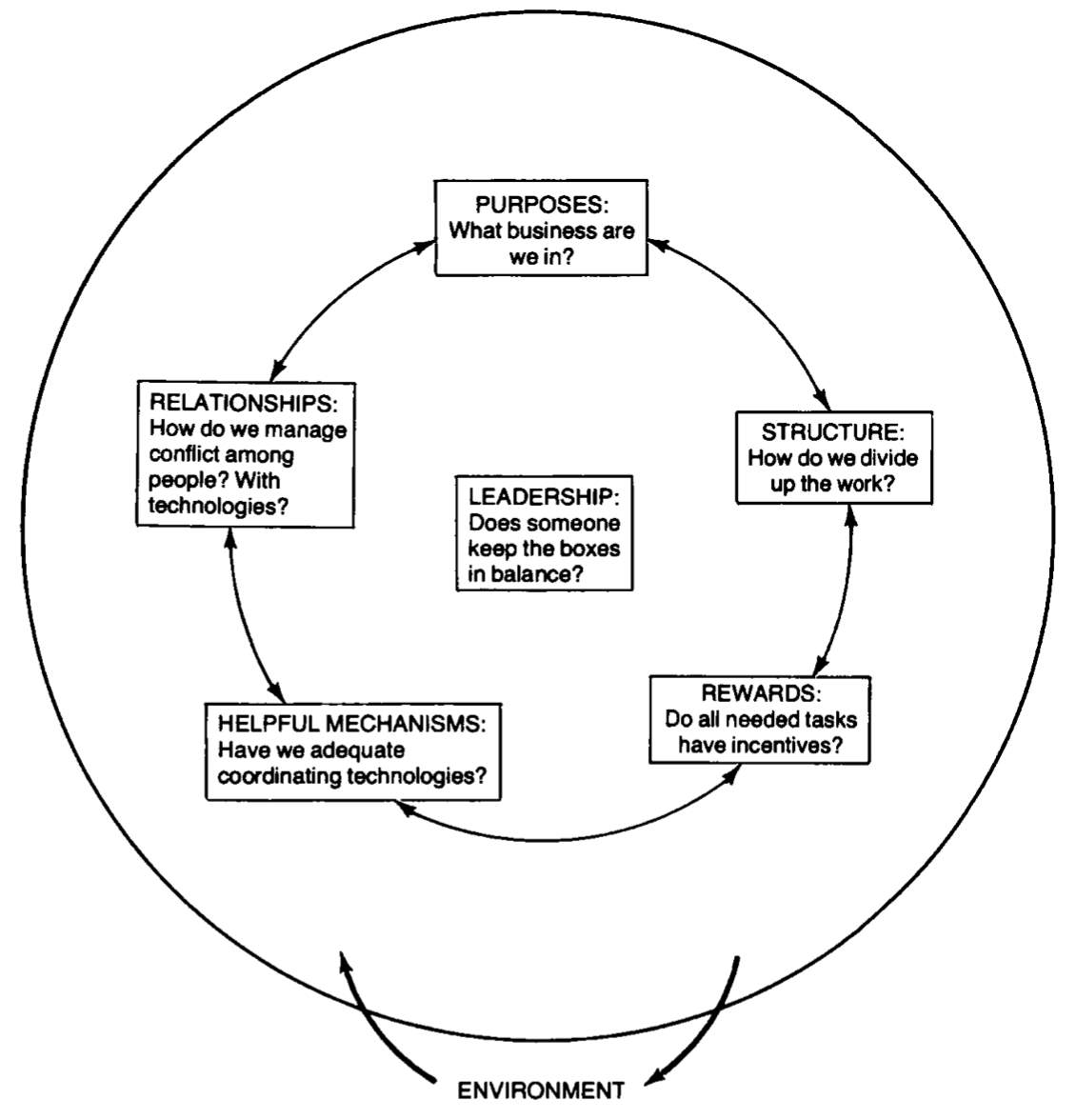

Literature has suggested several models that can be used to conduct organizational diagnosis (e.g. Gavrea et al., 2011; McFillen et al., 2013). For the purpose of assessing the KX change effort performed by Accenture, this paper will use the six-box model developed by Weisbord in 1976. Weisbord’s six-box model is the most widely used model to perform organizational diagnosis due to its simplicity yet providing comprehensive insights in evaluating the different aspects of an organization (Kontić, 2012; Yousefi and Sajadie, 2014).

Weisbord’s six-box model divides organization formal and informal aspects into six different variables, namely purpose, structure, relationships, leadership, rewards, and helpful mechanisms (Duncombe, 2017b). The Purpose dimension is about the organization mission and objectives. Structure determines how the tasks are formally grouped and coordinated. Relationship concerns about the interaction between people, units, and technology of the organization. The Leadership dimension evaluates how the leaders influence a group and keep the balance between other variables. Rewards are the financial and non-financial valuations given for employees for completing the assigned tasks. Helpful mechanisms refer to the procedures necessary to coordinate the technologies and forces to support the organization to achieve its goals (Yousefi and Sajadie, 2014; Gavrea et al., 2010). The relationship between each variable is interdependent with each other, with Leadership is at the centre of the model, and Environment outside the circle and influence all the variables (Weisbord, 1976; Gavrea et al., 2010), as pictured in figure 3.

Figure 3, Weisbord six-box model. Source: (Weisbord, 1976, p. 432)

Weisbord (1976) suggested that both formal and informal aspects exist in an organization and that these aspects influenced the six variables, therefore should be considered while evaluating using the model. The formal aspect is based on what the organization says, usually represented in the paper, or can be verbally spoken. Whilst, the informal aspect considers what the organization actually do and the behaviour of the people associated with the organization (Weisbord, 1976). Duncombe (2017b) suggests that the higher the gap between these aspects in each variable, the more likely that this variable will be a source of problems for the change efforts.

This section will assess the overall Accenture KM strategy using the six dimensions defined in the Weisbord’s six-box model and taking into considerations both the formal and informal system of the initiative.

In the Purpose dimension, Accenture has a vision of becoming a ‘one global firm’ and provide the best solutions to its clients. Its KX strategy is supposed to be the representation of Accenture vision by the ability of their consultants to share and appreciate their knowledge and collaborate across its global organization. However, the findings indicate that there is a lack of submitted knowledge in the East Asia region with some Asian interviewees mentioned that they doubt their knowledge is appreciated. This is also indicated by most U.S. consultants were not aware of projects in Asia and do not inquire knowledge from their colleagues in Asia.

This lack of participation in Asia and awareness of projects in other regions further suggested that Accenture’s ‘one global firm’ is not yet achieved.

Regarding the Structure dimension, Accenture has prepared to allocate dedicated staffs to implement and manage its KX strategy. It has allocated around 500 KM staff members globally to promote the knowledge sharing between consultants and manage the knowledge databases. Nevertheless, the findings suggested that Accenture does not provide adequate support for local and cultural challenges. Although they assigned dedicated staff for managing KX, it does not consider resources to help consultants translate for local offices. This resulted in the consultants having to allocate extra time to translate the documents which made them unenthusiastic to translate the documents in a foreign language.

In terms of Relationship dimension, although there is no evidence of any poor interactions between the consultants and the KX system, Accenture seems to not fully consider the relationship of their consultants between the regions. As mentioned above, only few U.S. consultants sought out experiences from the Asia region. This showed a lack of knowledge appreciation from the consultants outside the Asia region, causing low numbers of submitted knowledge from the Asian consultants. Furthermore, the KX system does not provide a feedback mechanism to show that the knowledge submitted is being utilized.

For the Rewards dimension, Accenture applies a one-size-fits-all policy to all its offices including the rewards system in achieving its vision of becoming ‘one global firm’. However, it seems to have overlooked the challenges, particularly the cultural differences between countries, in implementing this type of policy. It provides little support to address the local challenges. The findings suggested that Japanese consultants tend to wait for instructions to submit documents because it is associated with promotion. A different situation is found in China, in which the Chinese people is not keen to do something voluntarily, without having any direct benefit to themselves.

In the Leadership dimension, Accenture’s top management as the Sponsor has provided an immense financial support reflected by its decision to invest more than $500 million to support the change initiative. It also has tried to influence the change effort by making it mandatory to submit post-project knowledge to KX. Nevertheless, it seems that this policy is not well thought of and communicated clearly as several interviewees in Asian offices thought that this policy does not apply to them. This is because some projects are very local in nature and there are no clear directions on what kind of projects that needs to be captured.

Regarding the Helpful Mechanisms dimension, Accenture has allocated a huge amount of budget to support the technology development and the people involved in their KM strategy. The Knowledge Exchange (KX) system was developed to support the effort in terms of collecting, storing, and accessing the submitted knowledge using electronic means. Moreover, it has assigned dedicated staffs acting as the owner of the KX. However, despite of these support mechanisms, it seems to lack other helpful mechanisms such as flexible policy specific for local offices. The findings implied that the Asian offices wished that the organization allow more flexibility at the local level, in terms of incentive programs, language choices, and document formats.

Overall, having assessed the Accenture KX implementation, it can be concluded that the change initiative is a partial failure. Partial failure is the condition in which only few initial objectives are achieved or if there are significant undesirable outcomes from the change effort implementation (Heeks, 2002). In the case of Accenture KM change initiative, while it can be considered as a success within its Western regions, it faced obstacles in its Asia region resulting in low level of participation and inconsistencies in the quality of knowledge submitted to KX.

After assessing Accenture KM strategy using the Weisbord’s six-box model in the previous section, it is evident that the company faced several constraints in their change effort. It encountered challenges ranging from local context such as culture to global context such as worldwide company policy.

One of the main constraints faced by Accenture is the challenges specific to the local context. Based on the assessment, Accenture seems to have overlooked the barriers of local language. The knowledge submitted into KX should be submitted in English, meaning that the consultants, whose documenting their work in the local language need to provide extra effort to translate the documents into English. Furthermore, the findings suggested that while most Asian consultants are conversant in English, they are not adept in translating professional documents accurately. Additionally, it faced cultural constraints in terms of rewards associated with KX contribution. The culture of Japanese people which preferred to wait for instructions because it is associated with self-promotion affected the KX contribution from their Japanese consultants. While the culture of Chinese people which is only interested in giving extra effort if there is a benefit to themselves has influenced the Chinese consultants’ contribution. It is evident that Accenture’s one-size-fits-all policy only provide little considerations regarding cultural aspect.

Another main constraint that Accenture might have overlooked is the lack of sense of ownership and camaraderie among its consultants. The findings indicated that the company has not been able to successfully create a strong sense of ownership. Limited interaction with the headquarter, lower salary for consultants in Asia region, and few Asian consultants promoted to senior positions have made Asian consultants felt demotivated to give contributions to KX. Moreover, there seems to be a lack of awareness between consultants in different regions. The interviewees confirmed that most U.S. consultants are not aware of projects in Asia. There is also little inquiry for knowledge coming from the Asia region. To worsen the situation, the KX system does not provide any feedback whether the knowledge is being utilized or not. Collectively, these have resulted in the low camaraderie level among the consultants.

There are some recommendations or improvements that Accenture could do to improve the success rate of their overall KM strategy which would be further discussed below.

First, Accenture should consider the context of local culture. Culture, acts as an external variable that influences employee behaviours on their personal lives and within an organization, it influences the culture of an organization collectively (Dong and Liu, 2010, p. 224). Therefore, it is important that organization, especially global organization, learn the nature of the culture of the nations in which they operate to understand how their employees in different countries behave to design the best approach for its policy (Naor et al., 2010). In the context of Accenture KX, it has become evident that the company could have benefited by understanding the different culture of the East Asia region. It should reconsider on what kind of policy that can be applied as a one-size-fits-all policy and what cannot be applied. For example, it could allow more flexibility in terms of accepted document language or allocate translation resources, and rewards and recognition program specific to local offices (Paik and Choi, 2005).

Second, strong personal commitment and sense of ownership added with strong camaraderie is one key in achieving effective KM strategy (Glisby and Holden, 2003). The company could develop a mechanism that allows the consultants to receive feedback when their submitted knowledge is being utilized by their colleagues (Paik and Choi, 2005). Additionally, it could also facilitate discussions between consultants in different regions. Thus, building a strong sense of companionship among the consultants. It could also try to restructure their organizations to be more diverse especially in the senior position and creating more ways to interact with the headquarter to increase the sense of ownership globally.

Third, the company could have improved their communication strategy to raise awareness of knowledge from different regions and redefine what types of project knowledge should be submitted. The knowledge managers could be utilized to review and select good knowledge submitted from each region and communicate it corporate-wide to raise awareness that knowledge in one region might be relevant and useful for other regions. The findings suggested some projects can very local in nature and might be irrelevant to other regions (Paik and Choi, 2005). Therefore, the company should define and communicate the characteristics of the project that should be submitted.

In conclusion, implementing a KM strategy has proven to be useful for a company to achieve sustainable competitive advantage. Learning from past experiences could help to avoid the same mistakes, improve project planning, minimize risk, and improve the company product quality. The use of IT could help to facilitate the process of creating, storing, accessing, and transferring knowledge. However, every change has its challenges, especially when the change effort is implemented on a global scale. When a change is implemented in different countries, it should take into consideration the local culture of the country to develop the right strategy. An organization should also be able to create a strong sense of ownership and comradeship between the employees to create a culture of knowledge sharing as this culture is a key to achieving successful KM strategy.

You have to be 100% sure of the quality of your product to give a money-back guarantee. This describes us perfectly. Make sure that this guarantee is totally transparent.

Read moreEach paper is composed from scratch, according to your instructions. It is then checked by our plagiarism-detection software. There is no gap where plagiarism could squeeze in.

Read moreThanks to our free revisions, there is no way for you to be unsatisfied. We will work on your paper until you are completely happy with the result.

Read moreYour email is safe, as we store it according to international data protection rules. Your bank details are secure, as we use only reliable payment systems.

Read moreBy sending us your money, you buy the service we provide. Check out our terms and conditions if you prefer business talks to be laid out in official language.

Read more