Fit to Serve: A Proposal to Research the Effects of Physical Fitness Programs on U.S. Law Enforcement Agencies

Abstract

This is a proposal to research if a relationship exists between the presence of physical fitness programs at law enforcement agencies and overall agency performance. The research question is “How do physical fitness programs affect law enforcement agencies?” The goal of the study is to determine whether or not the presence of physical fitness programs could potentially make agencies better in certain quantifiable areas, thereby increasing the quality of police service they deliver. The study will attempt to examine existing statistics from U.S. law enforcement agencies (both with and without physical fitness programs) in conjunction with police officer and citizen surveys in an effort to determine the relationship, if any, among and between numerous variables. The implications of this research could be far reaching in terms of U.S. law enforcement. Chiefs and department heads could utilize the findings when making determinations about program implementation and policy decisions, as well as conducting cost/benefit analyses and officer retention decisions.

Introduction

There is little argument amongst the research that physical fitness either has been, or has become, an increasingly important aspect of public safety jobs in general, but even more so in law enforcement, and for more reasons than one may initially think. Anderson et al (2001) stated “There is no doubt that the physical demands of police work are higher than those occupations of a more sedentary nature.” (p.8). There appears to be a “general consensus” that police officers should be physically fit it order to meet the demands of the job (Means, Lowry, & Hoffman, 2011). However, in addition to addressing the physical nature of actual job requirements, the presence or absence of physical fitness programs at law enforcement agencies could potentially have a multi-faceted impact on the agencies themselves, and the service they provide the community.

This proposal seeks to address the question “How do physical fitness programs affect law enforcement agencies?” The goal of this study is to determine what type, if any, of a relationship exists between the presence of physical fitness programs at law enforcement agencies and several factors or aspects of the agency where the programs are present. The aspects used for examination would be expressed in terms of agency cost, agency health, agency effectiveness, and agency liability. Agencies and departments could potentially face civil liability for putting officers on the street that are not physically prepared to handle job-related tasks (Bissett, Bissett, & Snell, 2012). This research is important because it moves past the correlation between being physically fit and performing basic job functions and moves toward potentially showing that the presence of physical fitness programs also contributes to the betterment of the agency as a whole, and therefore would increase or improve the quality of police service.

This study will separate law enforcement agencies into three categories: those with mandatory physical fitness programs, those with voluntary physical fitness programs, and those with no physical fitness program present. The goal of the research is to show the differences (if any) between the departments in the above-mentioned areas. The study will also examine two different types of fitness measurement or testing, which are job task simulation testing and physical fitness testing. The reason for this is to see, among those departments with programs present, if the type of program has any sort of influence on the factors.

Literature Review

Types of Programs

There are two primary types of physical fitness programs to be concerned with: mandatory and voluntary. Mandatory programs would require an officer to meet a certain standard as a condition of their continued employment with the agency. In a voluntary program, the agency sets a standard or level that it would like for its officers to meet, but there are no adverse consequences for failing to meet it. In addition to this, the agency could reward the officer for meeting the voluntary standard.

The potential negative impact of mandatory programs could be far reaching. One problem associated with a mandatory program is incumbent officers not being able to meet the minimum standards. In a study conducted by the Texas Commission on Law Enforcement Officer Standards and Education (TCLEOSE), it was reported that the majority of officers were not in favor of mandatory physical agility and physical fitness testing for incumbent officers (Bissett, Bissett, & Snell, 2012). This can be attributed to the fact that 27% of the officers surveyed reported they would not be able to pass a mandatory physical fitness or agility test (Bissett, Bissett, & Snell, 2012). This issue is an inherent problem with mandatory physical fitness programs. Departments all across the country are experiencing officer shortages and stagnant growth (“Police and Detectives: Occupational outlook handbook: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics,” 2015). With employment growth slowing, mandatory fitness requirements could unnecessarily cut much needed officers from the front lines. Possible further evidence of this problem is described in a 2014 longitudinal study by Pal Lagstead, et al. Police officers in Norway were given a physical fitness test upon graduating the academy in 1995. Those same officers were asked to participate in the same fitness test in 2011. Among both men and women participants, there was shown to be an overall decrease in the performance on the fitness test after 16 years of law enforcement work. Given the appearance of a demonstrated change in physical ability over time, it would seem that mandatory fitness programs could adversely affect agency retention rates. With regard to the initial research question “How do physical fitness programs affect law enforcement agencies,” conducting this study could theoretically show whether or not mandatory programs actually have a negative impact on departments as some of this previous research might suggest.

Another potential issue arising from mandatory programs could be potential discriminatory civil liability. The Civil Rights Act of 1991 established the “Same job – same standard” rule with regards to performance testing and requirements (Frequently asked questions regarding fitness standards in law enforcement, n.d.). If agencies are to comply with this federal law, the standards for male and female officers would need to be identical. This could theoretically pose a problem, as indicated in a 2013 study conducted by Jackson and Wilson. Females overwhelmingly failed the “Gender-Neutral Timed Obstacle Course” (GeNTOC) test more than males (Jackson & Wilson, 2013). Agencies wishing to raise the standard on their mandatory fitness program and requirements run the risk of the test being discriminatory toward females. Conversely, agencies that attempt to combat this problem by lowering the standard, run into an altogether different problem of the test not accurately measuring the job it is designed to replicate. Mandatory standards and programs are often not cost effective (Strandberg, 2014). If officers are required to meet a certain standard, then they may have to be provided with compensatory time and equipment to help them meet that standard. Also, mandatory programs that utilize job-related function tests as their testing procedure, would need scientifically-validated proof that the standard mimicked the job task in order to be successfully defended against a potential lawsuit (Strandberg, 2014). Strandberg acknowledges the existence of companies that help agencies develop defendable mandatory standards and programs, but argues they are often expensive and have long or drawn out implementation processes that most agencies cannot take advantage of.

The other type of fitness program available to police departments and agencies is the voluntary standard or model. In this method, agencies are able to set guidelines and goals for officers, while encouraging participation through the use of incentives such as extra pay, or days off for reaching certain goals. As an example, take an agency that utilized physical fitness testing in a voluntary model. It could set goals such as “Run 1 mile in under 10 minutes,” or “Complete the obstacle course in less than 8 minutes.” Officers that completed the tasks or met the goals could receive some sort of incentive. Compared to the previously discussed issues with mandatory policies, these initiatives theoretically allow agencies to promote fitness among the ranks and improve the quality of life and work for the officer, while controlling or minimizing risks to the agency itself.

Cost and time still could be a factor in the development of voluntary programs, however. Strandberg’s article highlights that officers should be allowed to work on their fitness goals while on-duty. Kelly Kennedy, a representative of FitForce, states that “Departments should be allowing officers to maintain fitness on the job. It should be encouraged and built into the work week, rather than having to somehow sneak around on a break to work in a quick set” (Strandberg, 2014, p.28). FitForce is a company that specializes in physical preparedness and readiness for public safety agencies. The company is utilized to evaluate and develop physical fitness programs for police, fire, and EMS departments. FitForce stated in its recommendation to CALEA (Commission on Accreditation for Law Enforcement Agencies) on developing a baseline fitness program “Perhaps the most important contribution the administration can make at this point, is to look for ways to allow on-duty training time. As mission and staffing permit, providing up to three hours per week for fitness training will have a significant impact on participation and adherence” (Model program: Public safety physical readiness, 2010, p. 17).

This could present multiple problems for some agencies. One issue immediately created is the time dilemma. As previously discussed, officers are busier now than ever, and departments and shifts across the country are working short-handed and doing more with less. Even moderate to large sized departments and agencies would be hard pressed to find three hours per officer during the work rotation (given they work 12-hour shifts) to spare an officer for working out. This problem would be compounded at departments or agencies that worked either 10-hour or 8-hour shifts. The other issue agencies will face when trying to adopt this recommendation, is money. Budgetary concerns are often at the top of department heads’ lists, and this would undoubtedly bring some additional costs. These costs would either come in the form of compensatory time for the officer, providing a workout space with equipment, or both.

Again, the question “How do physical fitness programs affect law enforcement agencies?” spurs research that would examine whether or not the presence of voluntary physical fitness programs helps or hurts an agency. It could also help when comparing departments that have voluntary programs versus those with mandatory programs, or no program at all. The research could potentially show that departments are actually better off in terms of the measurable factors than some of the previous research indicates.

Types of Testing and Measurement

Now that the two types of fitness related programs have been examined, the types of fitness tests, or measurements, must be highlighted. According to the Cooper Institute, there are two primary types of fitness standards or tests that can be administered to law enforcement officers: Job task simulation tests (JTS) and physical fitness tests (Frequently asked questions regarding fitness standards in law enforcement, n.d.). Job task simulation tests are tests that are designed to replicate job tasks and functions, and measure an officer’s ability to complete the tasks. Theoretically, an officer’s performance on the test would be a predictive indicator of their performance in the field.

Job task simulation tests, also referred to as agility tests or obstacle courses, are widely utilized by law enforcement agencies that employ some sort of physical testing. Bissett, Bissett, and Snell (2012), indicated that in 2003, 95% of city police departments and 76% of county sheriff’s offices used some sort of physical agility testing in their hiring process. This shows that a large portion of departments that have a physical fitness standard (whether it be mandatory or voluntary) are using job task simulation tests as their measurement. According to Means, et al in 2011, the following list includes examples of common physical activities police officers can expect to do as part of their daily routine: Walking and running short and long distances, going up and down stairs, jumping and vaulting over obstacles, climbing fences, crawling around, dragging victims, carrying, bending, reaching, pushing and pulling heavy items, using hands and feet in self-defense, and long-term use of force (Means, Lowry, & Hoffman, 2011).

One of the disadvantages to agility, or job task simulation tests, is the increased potential for discrimination against females. The 2013 Jackson and Wilson study highlighted the disparities between female and male scores on the “Gender-Neutral Timed Obstacle Course.” Similarly, Bissett et al stated in 2012 that “The use of physical agility tests has had a dramatic negative impact on the hiring of female police officers” (Bissett, 2012, p.210). The Cooper Institute claims that agility tests only measure about 20-25% of the actual physical tasks (Frequently asked questions regarding physical fitness standards in law enforcement, n.d.). With regards to the proposed study and research question “How do physical fitness programs affect law enforcement agencies,” this could have implications in terms of showing that just because a department employs a program, it might not actually be bettering the department in terms of the measurable factors. This could especially be possible if the standard of measurement is an agility or JTS test, as indicated by the previous research.

Conversely, physical fitness tests seek to identify underlying fitness areas as predictors of ability to perform job related tasks. Physical fitness tests analyze what tasks are physically necessary to do the job, and then correlate those tasks with a corresponding fitness test (Frequently asked questions regarding fitness standards in law enforcement, n.d.). The Cooper Institute, in conjunction with FitForce, conducted a validation study and identified the following physical fitness tests as being predictive of law enforcement job tasks: The 1.5 mile run, the 300-meter run, 1 rep max bench press raw score, 1 rep max bench press ratio score, push-ups, sit-ups, and vertical jump (frequently asked questions regarding physical fitness standards in law enforcement, n.d.). According to the Cooper Institute and Collingwood, Hoffman, & Smith (2003), those tests measure the following underlying areas that are predictive of law enforcement tasks: Aerobic capacity, anaerobic power, muscular strength, and muscular endurance (Collingwood, Hoffman, & Smith, 2003). A disadvantage of the physical fitness test battery could be the cost needed to thoroughly conduct validation studies for the individual departments. Although similar, each law enforcement agency patrols a different geographical region and therefore may require different physical skills that need to be addressed in their fitness testing and programs.

Potential Agency Implications

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, police officers are at a higher risk of work-related injury or illness than other occupations. From 2009 to 2014, police officers, on average, had 30,990 days away from their assignment per year due to injuries and illness (“Police and Detectives: Occupational outlook handbook: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics,” 2015). According to a CALEA report, the average cost to an agency of an officer suffering an on-duty heart attack is between $400,000 and $750,000. Heart disease makes up anywhere from 20 to 50% of early retirements, and nearly 35% of all back related issues (Smith Jr. & Tooker, n.d.). Given these statistics, as well as previous findings, the variables agency health and agency cost will be examined in the proposed study. Jay Smith, the founder and CEO of FitForce, argues increased “Fitness and well-being are correlated with better mood, better cognitive function, increased vitality, and less sick days” (Strandberg, 2014, p.25). Smith goes on to estimate that departments and agencies could see anywhere from $3 up to a $9 return on investment for every $1 spent on developing fitness programs and policies (Strandberg, 2014, p.25).

That estimate only examines the medical expenses that could potentially be saved. There are other ways agencies could possibly save hundreds of thousands of dollars: reducing the amount of lawsuit settlements as a result of excessive force claims. Guffey, Larson, and Lasley (n.d.) posit that officers in better physical shape will have reduced incidents of excessive force incidents due to their ability to be able to better physically control suspects. The proposed study and research question “How do physical fitness programs affect law enforcement agencies,” seeks to expound on previous research and measure these items in terms of the variables agency effectiveness and agency liability. Another potential reward for agencies comes in the form of positive public perception. Fitter officers present a better image to the public. Increased levels of respect for the force, along with community pride are not as tangible as potential monetary gains, but intrinsic in that police – community relations could improve, thereby not only raising morale, but would result in overall improvement in the quality of police service that is delivered. The proposed study will attempt to categorize these findings in terms of the variable agency effectiveness.

Summary of the Literature

This literature review, while not exhaustive, represents a varied view of police fitness programs, their components, and their potential effect on law enforcement agencies. More current research (2010 and newer) is limited. This shows a demonstrated need for further study into the area of how physical fitness programs affect law enforcement agencies. The previous literature paints a portion of the picture, but the proposed study will attempt to broaden the scope with which departments and agencies are examined. By utilizing variables like agency cost, agency health, agency effectiveness, and agency liability as measuring sticks and comparing them against the variables of mandatory and voluntary fitness programs the current study would be able to expound on previous research and provide a better indication as to how departments and agencies are affected.

Hypothesis, Relationships, and Operationalization

This study seeks to make a determination on the potential effect physical fitness standards have on law enforcement agencies. In doing so, the study will examine the relationship between physical fitness programs and four factors:

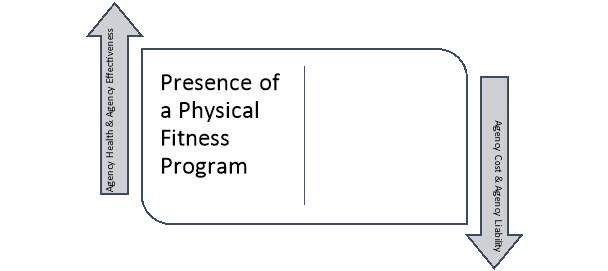

The hypothesis is that the presence of a physical fitness program (independent variable) will cause agency health and effectiveness (dependent variables) to rise, while also lowering agency cost and liability (dependent variables). In the study, the four factors would be expressed in terms of the following attributes:

Measurement of the attributes that culminate in each factor could be done via a type of index. For example, the more medical expenses an agency pays out, and the more money that is spent on litigation and civil suits, the higher the variable agency cost will be. The more sick-days and on-duty injuries that are reported, the lower its level of the variable agency health will be. Higher levels of reported morale, increased numbers of arrest, increased numbers of arrests after foot chases, and high levels of reported public perception will raise the agency effectiveness variable. High numbers of use of force reports, excessive force complaints, and lawsuits settled or lost as a result of excessive force will increase the variable agency liability. Ideally, agencies would want to increase health and effectiveness while lowering cost and liability. Given the research question, agencies would then be categorized according to the presence or absence of a physical fitness program to examine if a relationship exists. This can be even further delineated by separating those agencies with mandatory programs versus those with voluntary programs. See the below picture for a diagram of the theorized potential relationship between the primary variables.

Other variables that play a role in this study will be gender and age. Gender would be measured nominally using the attributes male and female, while age will be measured using a ratio. Officers would be categorized based on where they fall in an age range. In most states, you must be at least 21 years old to be a police officer. The age brackets could be broken down into four (4) ten-year brackets: 21-30, 31-40, 41-50, and 51 and above. The majority of states require officers to work either 20, 25, or 30 years to be eligible for full retirement. Utilizing the ten-year age bracket would allow the research to examine where officers’ fitness level placed them during the beginning, middle, or end of their career. Given that the previous research indicated a sharp decline in officer performance during the latter portions of their career, this bracket allows for quick comparison among departments with physical fitness programs and could show whether or not longevity is an issue with the programs in place. It should be noted here that public perception is included in the overall agency effectiveness factor because public perception directly impacts and guides an agency’s policies, procedures, and performance. Officers that are deemed to be physically fit by the public present a strong, positive, and most importantly, safe public image. Citizens that view their officers as physically fit could likely report feeling safer or more secure as opposed to having police officers that are overweight and out of shape. This “citizen approval” goes a long way in increasing officers’ overall morale, which, as seen in the literature, could contribute to reduced stress and therefore fewer incidents of sick days and injuries.

Research Design

This study would make best use of a mixed-method research design. Combining the qualitative aspects of survey research with the unobtrusive research style of analyzing existing statistics would theoretically not only provide a deeper understanding of the data, but also increase the validity of the study as a result data triangulation (Babbie, 2016). The focus of this study seeks to be a combination of the three research purposes: exploration, description, and explanation. It will be exploratory in that there is already a certain level of familiarity with some physical fitness programs and requirements, but a better understanding of the role they play in the day to day operations of the agencies and the overall furtherance of the profession in general is the ultimate goal.

The study will also be descriptive. Data will theoretically be available across a wide range demographics, but chief areas of interest would be age and gender. The reason for this is because law enforcement agencies could utilize the data when deciding whether or not to implement fitness programs. The decision to make the program mandatory or voluntary (or implement one at all or even take one away) could come down to how females and older officers performed over the course of their career. The study would then, hopefully, be able to describe how differing age ranges and gender profiles perform on physical fitness tests and how different departments employ the tests across the ranks to begin with.

The study should also be able to describe the agency breakdown of officers and their performances on the tests. This would help in painting a broader picture of the profession, in terms of agency comparisons and, in turn, show whether or not the programs or requirements help or hurt the agency. Finally, the study will also involve explanation. According to Babbie (2016), the purpose of an explanatory study is to answer the question why. Theoretically, at the end of this study, agencies would be able to examine the available data and be able to determine and explain if the implementation of physical fitness programs are a good idea or not, and if they are, which type would better suit their department.

The unit of analysis in this study are the law enforcement agencies across the United States. Since the actual departments do not perform anything physically, the units of measurement will be the individual police officers that comprise the departments. In studying an aggregate, in this case, police departments, care must be taken not to commit the ecological fallacy. This occurs when conclusions are drawn about the whole group based on the performance or characteristics of the individual units that make up the group (Babbie, 2016). A way to combat that with this study would be to retest the conclusions using a different set of factors, or attributes comprising that factor. For example, instead of using arrest rates as an attribute of agency effectiveness, crime rate per capita could potentially be examined.

Validity

With regard to threats to validity, when examining statistics or data that already exist such as in this proposed study, there is an inherent risk that the presented data doesn’t exactly match the study purpose. This could lead to incorrect conclusions based on a misrepresentation of the variables (Babbie, 2016). Babbie (2016), outlines two ways to combat this issue and this study employs both of them. The first is logical reasoning. It would be logical to think that departments with physical fitness programs in place, whether they be voluntary or mandatory, would have fewer incidents of injury and fewer medical expenses paid since the officers would, theoretically, be in better shape. The other way the study combats the validity threat is replication with regard to interchangeability of indicators. This means that certain indicators, taken by themselves, are not necessarily conclusions of a fact or measurement of an entity (Babbie, 2016). In this study, low agency cost and high agency health might not, by themselves, show that an agency is more fit than another. However, if all or the majority of agencies with physical fitness programs present are reporting these, then it could be inferred that the presence of physical fitness programs has had an impact on the agency. This study, by design, accentuates this solution by providing numerous variables and attributes for exploration.

Reliability

When analyzing existing statistics, one must take care to ensure the “quality of the statistics themselves” (Babbie, 2016, p.338). In the case of this study, the statistics will mostly come from the agencies themselves. The numbers and figures would theoretically be fairly reliable, since some of them are tied to financial records and it would be safe to think that agencies kept these types of records accurate. Babbie (2016), also cautions about the use of government statistics, especially with regard to crime rates. Although arrest rates could be taken from the Bureau of Justice Statistics if needed, a more accurate arrest count could be taken from the agencies themselves. In the case of the attribute of “Number of arrests following a foot chase,” this information would have to come from the reporting agency, as this is not a required or even requested statistic on the FBI’s Uniform Crime Report (UCR).

Data Collection

As mentioned in the research design, data collection will come in the form of unobtrusive research, or, analyzing existing statistics. The sampling frame should include law enforcement agencies from across the country. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, there are currently about 18,000 total law enforcement agencies operating in the U.S. This includes federal and state agencies, as well as local police, county police, Sheriff’s Offices, sworn campus police, and tribal police. These agencies vary by the number of sworn employees they have, as well as by the age, gender, and race of the officers that make up the department. In order to determine the impact that physical fitness programs have on a department, it will be necessary to examine departments of all sizes and makeups that both have, and do not have any programs in place.

The sampling method that would likely be most useful in this study is purposive sampling. The purpose of the study is very narrow in its scope, in that, it is concerned only with police departments and sworn police officers. According to Babbie (2016), knowledge of the study population and its elements are both valid reasons for selecting this approach. These reasons apply in this study because the population (police departments and police officers) and their elements that make them up are very specific in nature. Babbie (2016) also outlines utilizing this method of studying a smaller subset of a larger population when it would be extremely difficult to study all of them, or the whole population. This is the case in this study. With nearly 18,000 law enforcement agencies, identifying all of the ones with physical fitness programs in place would be very difficult. Using purposive sampling, the study would utilize data from a large portion of identifiable departments with programs in place, and this should provide sufficient information.

The study could theoretically also employ snowball sampling. This technique, is used to locate subjects when they are members of a special population or otherwise difficult to find (Babbie, 2016). In the case of this study, the snowball technique could be used to discover other agencies or departments with similar physical fitness programs or even an agency that the current one based its program on. For example, if examining a police department with a particular set of standards or a certain program, that department head could point the researcher in the direction of the department that they modeled their program after. This type of sampling could continue and be used through departments of all sizes and program attributes. The advantages of purposive and snowball sampling in this study are highlighted due to the nature of the study itself. The research is concerned with a specific group and, in particular, how that group is affected by a certain set of circumstances (the physical fitness programs). Purposive sampling seems to be the most appropriate choice because the research isn’t necessarily concerned with the population of the entire country, rather only police departments and police officers.

It should be noted that there is an aspect of this study that includes a “citizen,” or public perception element. This element, while not directly related to officer physical fitness, is important to determining the variable officer effectiveness and its attribute, overall public perception. As previously mentioned, physically fit officers could relay a more positive and safe image to the community that they serve. Positive public perception goes toward increasing officer and agency morale which, in turn, would increase agency effectiveness. In choosing a sampling method for surveying civilian citizens, probability sampling would yield more accurate results, since the research would be concerned with the opinion of the citizenry as a whole.

Ethical Issues

Most of the ethical concerns in this proposed study would likely come in the form of personal information collection and release. The majority of the research revolves around examining information from events that have already taken place, e.g., looking at police departments’ physical fitness tests and results. These tests and results would likely contain varying pieces of identifying information such as names, ages, races, genders. They could also possibly contain information such as preexisting medical conditions.

Actual access to the names, races, and birthdays of the people whose information is being collected is not needed. Attention only needs to be given to their gender, their age, and their score on a physical fitness test (if applicable). As far as the individual officers are concerned, this aspect of the research poses no risk. If the names on the information were redacted prior to receiving the information from the department, there would be no way to tie the results to any one specific officer. Having said that, there could be some issues with regard to data collection from the individual police departments. For example, after examining all of the information that was gathered, the research might show that Police Department A has x% of males and x% of females that are or are not meeting the department physical fitness standard, or males at Police Department B between the ages of 36 and 45 were x% below the average when compared to other departments across the country.

This information, in and of itself, is not sensitive in nature or compromising in any way. However, the release of certain facts or figures could potentially paint some departments in a more negative light than others. It would be up to the researcher to ensure the confidentiality of the information when reporting the findings, or formulating a recommendation. Certain factors, or pieces of information would not be able to be kept secret, even if all that was available was a citation at the end of the report. An example of this is information gained through a personal interview. Since this particular research would not be conducted utilizing actual participants performing tasks, there is no risk of physical or emotional injury. If the study were, however, to contain information that was obtained via survey, the information could be collected anonymously. For example: surveying individual officers at various departments regarding their opinions on physical fitness requirements, their current physical fitness level, etc. The surveys could be mailed to the departments, filled out, and returned without ever having to know the actual officers that filled out the information. They could also be sent and collected electronically, which would also reduce the likelihood of information being accessed by an unwanted party. The personal information needed from the survey would be minimal, and be similar to that collected from the department data listed above.

With regard to the citizen survey instruments, next to no identifying information would be needed other than an age range, gender, and residency status. This information would not be able to be tied to an individual person, so this aspect of the research would be anonymous as well. An informed consent form will be provided. The police departments would get a slightly different form, as would the individual officers. With regard to obtaining physical fitness test scores from agencies, if the department did not provide redacted information, only the specific pieces of information needed for the research would be transposed. For example, if a physical fitness test score sheet was provided with someone’s complete name, date of birth, employee number, and score, only their age, gender, and score would be transposed to the research documents, eliminating the risk of individual officers’ scores being published. Depending on the other types of information collected, there could be other steps taken to mitigate the risk of compromising personal data. However, there is not much personally identifying information that is needed to conduct the study.

Analysis

The research question for this study is “How do physical fitness programs affect law enforcement agencies?” The study seeks to examine the relationship among and between multiple variables, many of those being independent variables. Given this, two options appear at the forefront for multivariate data analysis, and they are path analysis and factor analysis. Path analysis, according to Babbie (2016), can show a causal relationship between many different variables in a graphic format. This method could potentially work for this particular study, since there are multiple independent variables (agency health, agency cost, etc.) that could be affected by the dependent variable (physical fitness programs) in varying degrees. This last aspect is the most appealing part of path analysis. According to Babbie (2016), the strength of the relationship between pairs of variables is shown while keeping the relationships between the others constant. “The strengths of the relationships are calculated from a regression analysis that produces numbers analogous to the partial relationships in the elaboration model (Babbie, 2016, p.471).

Factor analysis, conversely, uses an algebraic style method to determine a set of factors or “dimensions” that exist within some given observations (Babbie, 2016). This method appears to be better suited to this research study. This is because the study contains, what some would consider, to be a large number of variables. There are the four primary variables (potentially factors): agency cost, agency health, agency effectiveness, and agency liability; and then there are the attributes of those factors which could almost be considered variables themselves. In addition to gender and age, there are job task simulation tests or physical fitness tests. Babbie (2016) argues that factor analysis is the most efficient way of discovering “predominant patterns among a large number of variables (p.474). The use of a computer program is necessary to complete the function, but instead of having to compare the potential correlations, (be it simple or multiple) among and between all the variables, factor analysis computes this and presents it in a manner that is easy for the reader to interpret.

Conclusion

This proposed study asks the question “How do physical fitness programs affect law enforcement agencies?” The goal of the study is to determine whether or not the presence of physical fitness programs could potentially make agencies better in certain quantifiable areas, thereby increasing the quality of police service they deliver. The study also seeks to determine if, given the presence of a program, one type of program produces more of an effect than another, i.e., mandatory versus voluntary. The study is concerned with law enforcement agencies in the United States, regardless of size. The research will attempt to determine the relationship, if any, among and between mandatory and voluntary physical fitness programs and several variables to include agency health, cost, effectiveness, and liability. Observations will also be made with regard to men versus women, as well as age range of the individual officers that comprise the agency makeup.

The hypothesis is that, in the presence of physical fitness programs, agency health and effectiveness increase while agency cost and liability simultaneously decrease. The theoretical implications are that physical fitness and physically fit officers improve the department as a whole and increase the quality of the police service that is delivered. The study will attempt a multivariate analysis in the form of factor analysis to determine the relationship, if any, among the numerous variables.

References

Anderson, G. S., Plecas, D., & Segger, T. (2001). Police officer physical ability testing – Re‐validating a selection criterion. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 24(1), 8-31. doi:10.1108/13639510110382232

Babbie, E. R. (2016). The practice of social research (14th ed.). Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

Bissett, D., Bissett, J., & Snell, C. (2012). Physical agility tests and fitness standards: perceptions of law enforcement officers. Police Practice and research, 13(3), 208-223.

Collingwood, T., Hoffman, R. J., & Smith, J. (2003, June). The need for physical fitness. Law & Order, 51(6), 44-50. Retrieved from https://0-search.proquest.com.bravecat.uncp.edu/pqrl/printviewfile?accountid=13153

Frequently asked questions regarding fitness standards in law enforcement. (n.d.). Retrieved from The Cooper Institute website: https://www.cooperinstitute.org/vault/2440/web/files/684.pdf

Guffey, J. E., Larson, J. G., & Lasley, J. (n.d.). Police officer fitness, diet, lifestyle and its relationship to duty performance and injury. Journal of Legal Issues and Cases in Business.

Jackson, C., & Wilson, D. (2013). The gender-neutral timed obstacle course: A valid test of police fitness? Occupational Medicine, (63), 479-484. doi:10.1093/occmed/kqt102

Lagstead, P., Jenssen, O., & Dillern, T. (2014). Changes in police officers’ physical performance after 16 years of work. International Journal of Police Science & Management, 16(4), 308-317. doi:10.1350/ijps.2014.16.4.349

Means, R., Lowry, K., & Hoffman, B. (2011). Physical fitness standards. Law & Order, 59(4), 16-17. Retrieved from https://0-search.proquest.com.bravecat.uncp.edu/docview/868858765?accountid+13153

Model program: Public safety physical readiness. (2010). Retrieved from http://www.fitforceinc.com/files/Model%20Program.pdf

Police and Detectives: Occupational outlook handbook: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2015, December 17). Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/ooh/protective-service/police-and-detectives.htm#tab-1

Smith Jr., J. E., & Tooker, G. G. (n.d.). Health and fitness in law enforcement: A voluntary model program response to a critical issue. CALEA Update Magazine, (87).

Strandberg, K. W. (2014, December). The future of fitness. Law Enforcement Technology, 24-28. Retrieved from http://officer.com

You have to be 100% sure of the quality of your product to give a money-back guarantee. This describes us perfectly. Make sure that this guarantee is totally transparent.

Read moreEach paper is composed from scratch, according to your instructions. It is then checked by our plagiarism-detection software. There is no gap where plagiarism could squeeze in.

Read moreThanks to our free revisions, there is no way for you to be unsatisfied. We will work on your paper until you are completely happy with the result.

Read moreYour email is safe, as we store it according to international data protection rules. Your bank details are secure, as we use only reliable payment systems.

Read moreBy sending us your money, you buy the service we provide. Check out our terms and conditions if you prefer business talks to be laid out in official language.

Read more