Effects of early home language environment on perception and production of speech

Lily Tao and Marcus Taft

Presented by: Danielle Macedo

INTRODUCTION (200-400 words)

The main question of this study is what are the consequences of parents who have migrated to a new country and speaking to their children mostly in their native tongue rather than mostly the accented-new language/majority language of the new country? Some theories are that if the parent speaks mostly in their native language, children will likely be fluent in both languages; however, a negative consequence that might result is that the native language may interfere with attaining the second language. On the alternative, theory suspects that if parents speak with mostly the new language, this may prevent interference with the second language, and yet interfere with fluency in the first. Previous studies have found that the higher amount of exposure to one language over the other showed better perception of speech sounds in that language for both children (Bosch & Sebastián-Gallés, 2003; Sebastián-Gallés & Bosch, 2009), and adults (Sebastián-Gallés, Echeverría & Bosch, 2005), showing short and long term effects. What is not yet known are the effects of perception and production of the new language when there is early and extended exposure to that language in accented speech. The researchers hypothesized that those mostly exposed to the Majority Language (ML) in childhood would have better skill in perceiving accented speech overall, even with unfamiliar languages. They also hypothesized that those exposed more to their Heritage Language (HL) early on would be more disadvantaged in many aspects of their ML performance.

METHODS (150-300 words)

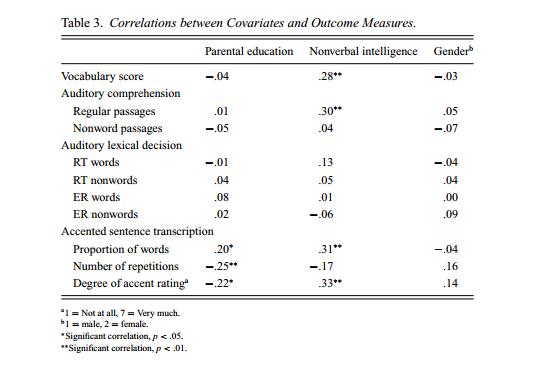

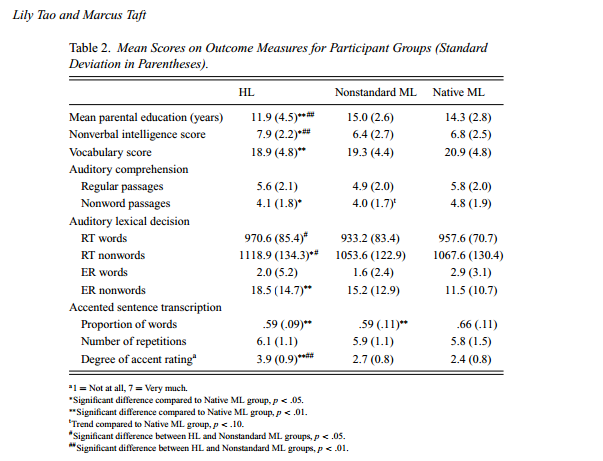

The participants were divided into the ‘HL’ and ‘Nonstandard ML’ groups depending if they reported their exposure to their non-English native language greater or less than 50%. They were also categorized based on proficiency in their English and any other languages. The final group was the ‘Native ML’ group which consisted of native English speakers. Age was also accounted for in gathering information about the subjects. The tasks included the following. For Non-verbal intelligence subjects were tested on a basic digital quiz that would serve as a baseline for following tasks. Vocabulary was tested also through a digital quiz to evaluate their breadth of vocab of course. Auditory Comprehension was tested by which they would answer questions, typing in response, based on an auditory sentence they heard; in this task they also tested with real word and non-word auditory sentences to evaluate their ability to recognize novel words. There was an Auditory lexical decision task which involved answering as quickly as possible ‘yes’ or ‘no’ depending on if the presented word was a real word or non-word. Another task was the Accented Sentence Transcription where they would type out a sentence they just heard, varying in accents from sentence to sentence. Finally, there was a Speech Production task where participants would verbally report back the sentence they had heard and their response recorded via microphone. The sentences would also be spoken in different degrees of accent which they would rate from 1=not at all to 7=Very much.

DISCUSSION (200-400 words)

The lower performance of the HL group in Vocabulary could be simply due to their delayed exposure to words. Also this is congruent with research that show how bilinguals have reduced vocabularies in both their native and second languages. In the accented speech task, HL’s may have performed lower simply because of their lack of vocab, as well as access to a similar lexical information to native ML’s, therefore the process by determining words from nonwords would be slowed. More research supports this by showing that nonnative listeners have more trouble with word recognition because of the interference of word candidates in their native language. This would also support their scoring on rating the accent as stronger because they may have thought they could not understand it, when really it was too quick to fully process. In the auditory comprehension task, monolinguals out performed early-learnt bilinguals in other research, suggesting that the first language can have negative impacts on the second language even if it is more dominant. Interestingly, the Nonstandard ML group, did not result in higher ability in perceiving unfamiliar accented speech, which contradicts the hypothesis. One interpretation is that perhaps the Nonstandard ML group tried to assign or assimilate novel variances of speech to ones that they know, incorrectly doing so, or perhaps not even assigned to a category, therefore glossed over. There might be some sociolinguistic factors that come into play when looking at the Speech Production task results; perhaps Nonstandard ML group participants were exposed to people in the community, therefore overcoming the nonstandard style given by their parents and performing well in Speech Production tasks. Another thought on this is perhaps people of this group are ‘bi-accentual’ meaning they use an accent at home different from the accent they use with their second language community. It’s important to note that the participants in all three groups performed similarly across cultural backgrounds; therefore, the results are from general language experiences and not confounded by specific cultural backgrounds. The study found no correlation between performance and things like socioeconomic status, age or gender. This article is interesting in that it puts into perspective that teaching a child earlier on will make them more proficient in their second language, however, even with the most equally balanced attention to both the native and second languages, there will always be a few linguistic shortcomings for them compared to ones that spent childhood learning their native language and native monolinguals of the second language.

REFERENCES

Best, C. T. (1994). The emergence of native-language phonological influences in infants: A perceptual assimilation model. In J. C. Goodman & H. C. Nusbaum (Eds.), The development of speech perception: The transition from speech sounds to spoken words (pp. 167-224). Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press.

Bialystok, E., Craik, F. I. M., Green, D. W., & Gollan, T. H. (2009). Bilingual minds. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 10, 89-129. doi: 10.1177 /1529100610387084

Nguyen-Hoan, M., & Taft, M. (2010). The impact of a subordinate L1 on L2 auditory processing in adult bilinguals. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 13, 217-230. doi: 10.1017/s1366728909990551

Portocarrero, J. S., Burright, R. G., & Donovick, P. J. (2007). Vocabulary and verbal fluency of bilingual and monolingual college students. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 22, 415-422. doi: 10.1016/j.acn.2007.01.015

Tao, L., & Taft, M. (2016). ‘Effects of early home language environment on perception and production of speech’. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 2 (7), p. 1-15. doi: 10.1017/S1366728916000730

Weber, A., & Cutler, A. (2004). Lexical competition in non-native spoken-word recognition. Journal of Memory and Language, 50, 1-25. doi: 10.1016/ S0749-596X(03)00105-0

You have to be 100% sure of the quality of your product to give a money-back guarantee. This describes us perfectly. Make sure that this guarantee is totally transparent.

Read moreEach paper is composed from scratch, according to your instructions. It is then checked by our plagiarism-detection software. There is no gap where plagiarism could squeeze in.

Read moreThanks to our free revisions, there is no way for you to be unsatisfied. We will work on your paper until you are completely happy with the result.

Read moreYour email is safe, as we store it according to international data protection rules. Your bank details are secure, as we use only reliable payment systems.

Read moreBy sending us your money, you buy the service we provide. Check out our terms and conditions if you prefer business talks to be laid out in official language.

Read more