SECTION 1

Scenario 1

(In this scenario, you are a partner in a reasonably large architectural practice).

Both of Mr Zhang’s projects – the traditional and the D&B – have been on site for several weeks and are progressing well, with you as architect and Project Manager on the traditional contract (using JCT Standard Building Contract With Quantities). Note: The client promoted you to Project Manager after dismissing the Engineering practice for what the client’s translator calls “insubordination” and challenging the client’s wishes. You have reached an amicable arrangement for a suitable fee and taken on the role in time to facilitate the tender processes.

Using efficient internal fire-wall procedures in your office, allied to your ISO9001 accreditation, you are also the novated architect on the commercial project (as detailed in Assignment 06). The start on site was negotiated to be the same for both contracts, with a 16-month construction period for the traditional build and 11 months for the D&B contract.

Mr Zhang and an entourage of Chinese business stakeholders/ potential investors have visited the adjoining sites. These visits were arranged with the contractors at short notice and without your knowledge.

Mr Zhang is clearly concerned that the below ground drainage – which is approximately 20% completed on both projects – is clay rather than the PVCu pipework which he was expecting to see. He wants to know why you are using a more expensive option, and whether it is feasible to change? The main contractor on the traditional contract has already suggested that there would be no problem for them to re-order new materials. The D&B contractor however, has suggested that not only is he changing to PVCu pipework (clay was in the specification for both projects), but he is also changing the rainwater downpipes from aluminium to PVCu and will be ordering PVCu baths and washbasins in lieu of the ceramic bath sets that were originally marked on the Stage 3 drawings. He says that he has discussed all this with the local planning office and that there will be no planning implications to this change.

The D&B contractor says that the “reasonable reason” for the change been press coverage about problems in the ceramic bath set market. He is worried that ceramic fixtures will delay the project (L&A damages are set at £1000/ day).

The D&B contractor also announces to the client – much to the client’s delight – that he will also be creating more usable floorspace in the commercial premises by omitting the downstairs disabled WCs altogether. All the above, he says, is not up for discussion and he wants you to amend the drawings accordingly “as he is entitled to instruct under the JCTDB16 contract”. You point to Wilkes v Thingoe but to no avail.

As you are about to leave, you notice that the damp-proof membrane on both projects, looks as if it has been laid directly on top of the hardcore instead of a 30mm sand layer. (for the sake of this paragraph, you represent the novated architect and NOT the traditionally contracted works). By late afternoon, you return to the office and check the relevant drawings for both projects and find that there are only 1:100 GAs and 1:100 sections but no specific 1:5 or 1:20 details of this element. Even though the section drawing looks correct, it is vague and contains no specific reference to “sand blinding”. However, you finally find a reference in the written specification: “The membrane should be installed on a compacted fine-grained sand blinding layer”. Tomorrow, the concrete slabs are being laid.

Your response(s), please.

The contractors are interested in PVCu pipes because this product is cheaper and easier to handle when installing. However, despite and its flexibility, PVCu has many shortcomings such as the material’s lack of inherent strength and vulnerability to poor site practice. In particular, a PVCu pipeline requires bedding of gravel or similar material to avoid flattening. This necessitates deeper site excavation and a significant amount of aggregate, which can be costly. Also, even bedded correctly, plastic life expectancy is limited (Core, 2018). Clay, on the other hand, is more environmentally friendly and it has high longevity and good structural integrity, which prevents deflecting or flattening under load. In addition, it is inert, which makes it highly resistant to chemical degradation (Naylor and WWT, 2007).

Besides, as mentioned above, 20 percent of the below ground drainage has already been completed on both projects. Changing the materials at that stage may delay the project, and thus can cost more than the fittings and drain pipes themselves (KCS, 2014). I will write to Mr Zhang to explain the benefits of using clay pipes for sewage system (mentioned above) and tell him that it is not feasible to change to PVCu pipes at this stage. Then, I will let the main contractor on the traditional contract know that he does not need to re-order new materials.

The D&B contractor, on the other hand, is making changes to the specifications for the project without discussing it with the client and me: He is changing the pipework from clay to PVCu and the rainwater downpipes from aluminium to PVCu. He is also changing baths and washbasins from ceramic (that were originally marked on the Stage 3 drawings) to PVCu, claiming that the problems in the bath set market will delay the project (L&A damages are set at £1000/ day). As mentioned by the local planning office, there will be no planning implications for the change of the pipe works. However, the client gave a great deal of consideration to the preparation of employer’s requirements so that the obligations of the contractor regarding design is clear (McNair and PwC, 2011). This include lists of approved products. Although the client lacks control over detailed aspects of the design in the Design and Build contract, it is still the contractor’s objective to deliver the client’s requirements (JCT, 2018a).

Moreover, the contractor has announced to the client that he will also omit the downstairs disabled WCs altogether and he asks me to amend the drawings accordingly claiming that he is entitled to instruct under the JCTDB16 contract (JCT, 2018a). However, removing the disabled WCs on the ground floor means the changing the plan, which can result in serious fines and delays to the project. In this respect, the contractor has failed to deliver the client’s requirements, and more importantly, there is a risk related to design and quality.

The adoption of Design & Build has reduced my influence on the project as the architect. However, I am also the contract administrator of the project, and construction contracts give the contract administrator the power to issue instructions to the contractor. This is known as ‘Architect’s instruction’ (JCT, 2018a). After discussing issues mentioned above with the client, I will write to the contractor to remind him that it is his obligation to make sure that the workmanship, goods, and materials are delivered in accordance with the contract. If he refuses to complete the project according to the employer’s requirements for the contract sum, I will issue instructions to him to remedy this, as the contractor will have to comply with the instructions (JCT, 2011).

Regarding damp-proof membrane, ‘Approved document C: Site preparation and resistance to contaminants and moisture’, states that “Any ground supported floor will meet the requirements if the ground is covered with dense concrete laid on a hardcore bed and a dam-proof membrane is provided” (GOV.UK, 2016). The membrane surface can only be effective if the surface has been properly prepared. Thus, a layer of sand must be used between the hardcore and the damp proof membrane to ensure that the surface is flat and smooth so that stones do not puncture the membrane layer and the foundation remains water tight. Although this is not specified in the 1:5 or 1:20 detailed drawings, it is clearly specified in the written specifications. The concrete slabs cannot be laid before the membrane layer is laid correctly, as it won’t meet the building requirements. I will contact both contractors immediately to resolve the issue.

Finally, the project as started on site, albeit at a reduced scale. The contract is the IFC16 and the insurance money ensures that the project will now be well-financed and because of the intensity of the fire, the demolition work was reduced to merely rubble clearances, rather than demolishing the structure: a further saving. The listed buildings were undamaged, and the council has concluded that it was an accident but does not require the old structures to be rebuilt/ replaced.

As the trench foundations are being dug, the contractor discovers a mix of soft spots and shallow buried rock, with an underground stream running through the middle of the site. You had not done the site survey yourself but based your details on the report of a “competent agent” that you appointed.

Breaking up and removal of the rock and excavating and filling/capping the soft spots will take up almost all the contingency sum for the first phase. Admittedly, the client has gained more than 10 times that sum in the fire insurance claim, but Mr and Mrs Davis are not happy.

Provide your initial thoughts and write a letter to explain.

(As usual, cite contract clauses and case law to help bolster your argument).

Site investigation survey is very important, as it helps ensure all aspects of the site and its risks are understood before the works start, providing the foundations for critical decisions on construction projects. Conducting as many investigations as possible before the works start help to avoid costly mistakes and project delays when the work is under-way (Aspin, 2018).

However, although trial pits and boreholes give an idea of the ground conditions, the exact site condition will not be exposed until full excavation (Steeds et al., 2018). This has been the case for our project: Although I have appointed a ‘competent agent’ to survey the site while digging the trench foundations, the contractor has discovered a mix of soft spots and shallow buried rock, with an underground stream running through the middle of the site. Undoubtedly, breaking up and removal of the rock and extra excavating and filling/capping the soft spots costs will all contribute significantly to the costs of the project. Also, discovering that at this stage will delay progress considerably in an unplanned way (Crawford, 2016).

Sometimes, digging the foundations a little deeper can solve the problem. Otherwise, such ground conditions may require more elaborate solutions than simple trenched foundations (van Tubbergh, 2012). For instance, using a hybrid foundation system may help eliminate unstable ground conditions while reducing the building costs, making a significant contribution to the success of the project (Clayton et al., 2016). Therefore, before starting the works, I will investigate the site myself once more. Conversations with neighbours and local builders may also reveal some background information that may help me form a picture of the chances of the site requiring specialist foundation work.

As a result of my investigation, if I am convinced that the ground conditions will be difficult, I will contract local building inspector for advice to provide adequate foundations or get in touch with a specialist -an independent structural engineer so they can undertake a site survey and prepare an investigation report recommending required courses of action (Crawford, 2016). However, I must be very careful in hiring a structural engineer, as their recommendation overrules the observations of the building inspector. Also, they are very cautious in their assessment of the site and thus may recommend more complex engineered solutions than needed to secure themselves (and to avoid PII claims), which may bring unnecessary costs to the project.

With regard the Mr Davies’ inquiry about contingency sums, I will write him to kindly explain that it is difficult to eliminate the risk of cost overruns below ground. However, a contingency sum has already been placed in the budget for such unexpected costs.

Dear Mr Davies,

It is in the nature of a construction project that the scope of the work is not entirely known until the work has been completed (Gould, 2016). This is because the details of a building site are unknown at the time a contract is entered in and/or additional works may be required during the construction stage. To cover such unexpected costs that may incur during the construction phase, a contingency sum is included in the contract as a provisional sum. A common example of the use of provisional sums is the excavation and construction of footings and foundations, landscaping or site works.

In terms of risks, most of the risks associated to the project are usually encountered in the initial stages, i.e. during the ground works, and many of those risks have been eliminated when the foundations are completed. However, please note that construction works always involve ongoing risks until the project is completed.

We have also included provisional sums in the contract for any unexpected costs or additional work that may arise. This is to ensure that you have a more realistic idea about all the potential costs, risks and possible outcomes associated with the project but also to work within a budget that will reflect the likely true cost of the project (Cameron, 2016). Having contingency sum helps reduce uncertainty and allows the design to evolve in an orderly fashion without compromising the project.

I hope that the above answers your questions satisfactorily. Should you have any further questions regarding contingency sums, please do not hesitate to contact me.

Yours sincerely,

A.C.

SCENARIO 3

The meeting with residents was reasonable successful and most local residents have been calmed down by Mr Copper’s barristerial rhetorical skills. Even though there is still a Section 171E temporary stop notice in force, the client has told the contractor to make up for lost time by working extended hours. After a few days, the external works are progressing steadily, the basement is on the first fix, and above ground, internal partitions are being removed and rooms reconfigured. The stop notice has 7 days to run, and the Planning Committee is sitting in a few days to make a judgement on whether to lift the notice earlier.

Meanwhile, Mr Copper reveals that he has been confident all along that his “ruse” would work. He rings you one evening, slightly drunk, to reveal that he “always knew” that revised Clause 83 in the new draft National Planning Policy Framework 2018 would prove him right in the end. He has friends in the Department who tipped him off, he says. He says that he never doubted that the scheme would go ahead as planned. “Mark my words”, he says, “my daughter’s music business will take off” and, more importantly, “I look forward to suing the council for every penny they’ve got” for delaying the project unnecessarily.

Explain the changes proposed in the(draft)National Planning Policy Framework 2018 and refer also to the contemporary issues around the Localism Act (as well as other legislative, regulatory, or contractual items).

How would you advise the client?

The Local Planning Authority has issued a temporary stop notice to Mr Copper because it alleged that there had been a breach of planning control under the rules introduced by section 171E of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990. Added to the act in 2004 (GOV.UK, 2017b), a temporary stop notice is one of the enforcement actions that are available to local planning authorities when there has been an alleged breach of planning control in relation to land (ODPM, 2005) and thus it requires that “the activity which amounts to the breach is stopped immediately”(GOV.UK, 2018a). A local planning authority can issue a temporary stop notice to “safeguard amenity or public safety in the neighbourhood; or to prevent serious or irreversible harm to the environment in the surrounding area” (GOV.UK, 2018d). Unlike stop notice which requires an enforcement notice to be issued, temporary stop notice is issued as a stand-alone notice, and its effect is immediate.

The Council has issued a temporary stop notice to Mr Copper because it believed that immediate action is required to halt an unlawful activity and/or development. By issuing a temporary stop notice, the Council has prohibited carrying out of all the activity specified in the notice. However, even though there is still a temporary stop notice in force, the client has told the contractor to continue to work. This is a serious issue, as it is an offence to contravene a temporary stop notice after it has been served to you. As Mr Copper has failed to comply with the temporary stop notice, he is now at risk of immediate prosecution in the Magistrates’ Court, for which the maximum penalty is £20,000 on summary conviction for a first offence and for any subsequent offence.

Besides, the stop notice has 7 days to run (a temporary stop notice is only valid for a period of 28 days), and the Planning Committee is sitting in a few days to make a judgement on whether to lift the notice earlier. Taking such unnecessary risks may put Mr Copper at a disadvantage: If the local authority learns that the works continue unlawfully, it can decide to take subsequent and alternative types of enforcement action, which may delay the project considerably. I will write Mr Copper to kindly explain that and ask him to stop the works immediately.

Moreover, Mr Copper believes that revised Clause 83 in the new draft National Planning Policy Framework 2018 has proven him right (Please see the Attachment 1 below for a brief critique of the draft NPPF 2018). Thus, he wants to sue the Council for issuing a temporary stop notice, which delayed the project. In my letter, I will explain Mr Copper that he cannot sue the Council for the revised Clause 83 of the draft NPPF 2018, as it was not in effect when the temporary stop notice was issued.

On the other hand, if he strongly believes that local planning authority’s decision to issue a temporary stop notice was not just, he can contact a lawyer, planning consultant or other professional adviser specialising in planning matters for advice (GOV.UK, 2018d) and; challenge the validity of the notice by judicial review, as compensation may be payable by the local authority “for any loss or damage directly attributable to the prohibition effected by the temporary stop notice” (ODPM, 2005). However, the circumstances in which compensation is payable are set out in section 171H of the Town and Country Planning Act 1990 (GOV.UK, 2017a). In summary, compensation is only payable if:

“a) the activity specified in the temporary stop notice was the subject of existing planning permission, and any conditions attached to the planning permission have been complied with;

b) it is permitted development (including under a local or neighbourhood development order);

c) the local planning authority issue a lawful development certificate confirming that the development was lawful;

d) the local planning authority withdraws the temporary stop notice for some reason, other than because it has granted planning permission for the activity specified in the temporary stop notice after the issue of the temporary stop notice” (GOV.UK, 2018d).

Therefore, I will advise Mr Copper to not to sue the Council, as his chances will be very slim.

Attachment 1:

A brief critique of the changes proposed in the(draft)National Planning Policy Framework 2018

On 5th March 2018, the Ministry for Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) published draft revisions to the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF) for consultation, which closes on 10th May (GOV.UK, 2018b). Overall, while the new policies introduce useful clarifications and proactive measures, some of the fundamental issues remain. There are key points to note: There are changes to improve affordability and address the need for housing as well as make effective use of land. Housing Delivery Targets are introduced to speed up housing delivery. There are reforms to Section 106 and the Community Infrastructure Levy (GOV.UK, 2010) to make the systems simpler and more standardised: Viability assessments are reorganised to regulate the negotiations for affordable housing contributions. In addition, the Green Belt protection policy got stronger, and there is enhanced protection for the natural environment.

The revised ‘Chapter 6. Building a strong, competitive economy’ incorporates new policy proposals. Paragraphs 82-83 make more explicit the importance of supporting business growth and improved productivity, in a way that links to key aspects of the Government’s Industrial Strategy. Paragraph 83 states that planning policies should “a)set out a clear economic vision and strategy which positively and proactively encourages sustainable economic growth, having regard to Local Industrial Strategies and other local policies for economic development and regeneration; and […] d)be flexible enough to accommodate needs not anticipated in the plan, allow for new and flexible working practices (such as live-work accommodation), and to enable a rapid response to changes in economic circumstances” (GOV.UK, 2018c).

However, it is very crucial that the policy changes on supporting business growth and productivity including the approach to accommodating local business and community needs in rural areas interpreted carefully (GOV.UK, 2018b). Therefore, great care needs to be taken in the application of such approaches to ensure that in practice this will help build real communities through introducing other forms of development other than just housing while providing flexibility to support investment.

SECTION 2:

1. What is the Uniclass classification system?How does it work and what are the benefits?

Uniclass is a hierarchical classification system for the UK construction industry. It includes consistent tables covering all construction sectors and classifying items of all scale to organise information throughout the design and construction process. (Delany and NBS, 2018b). Uniclass classification codes are mainly used by cost estimators for cost estimating and specification writing. However, they are also used by design professionals and consultants for classifying product libraries or naming systems in CAD and BIM software.

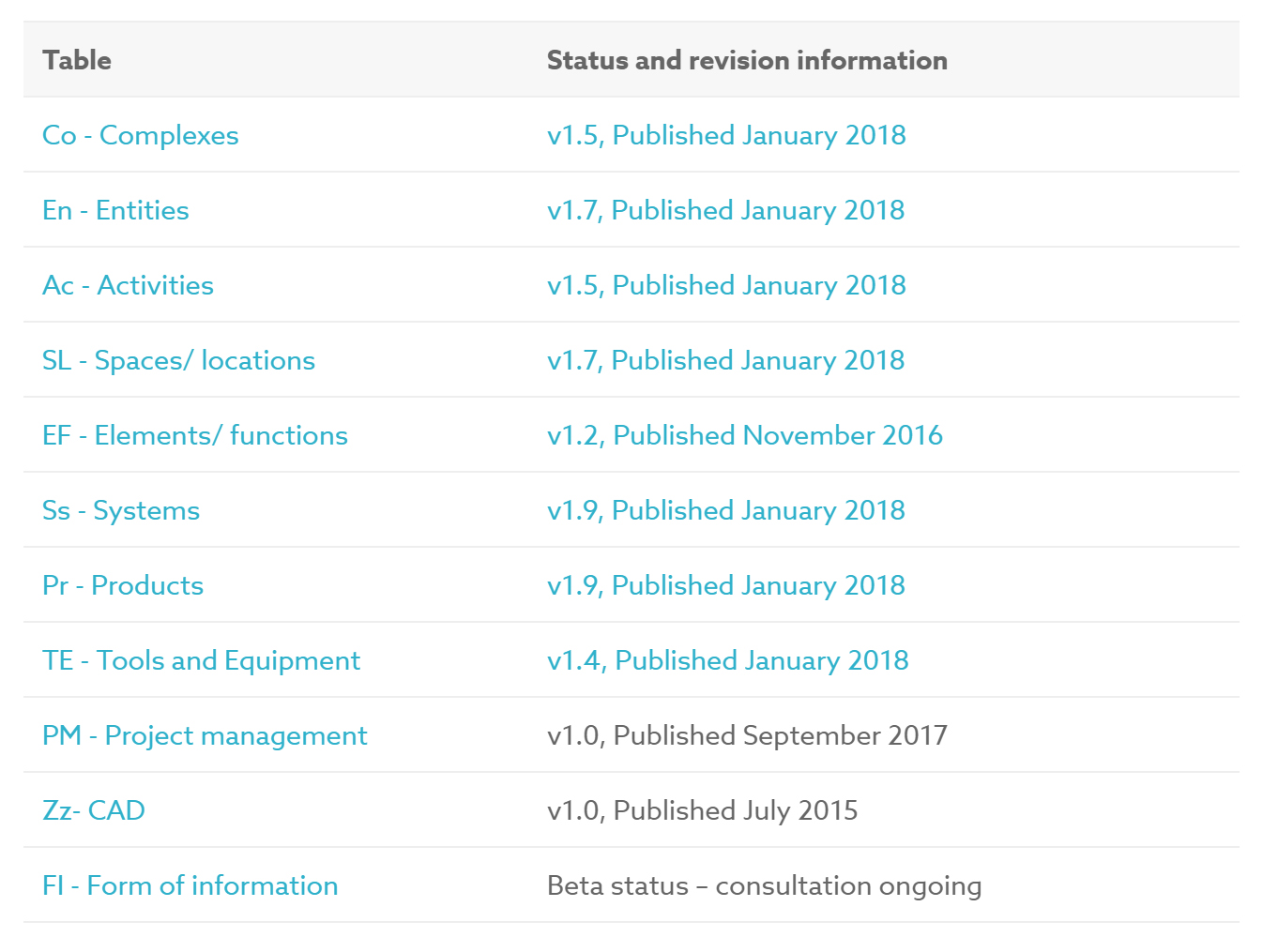

There are three versions of Uniclass classification systems: Uniclass, Uniclass 2 and Uniclass 2015. Uniclass is the original version created in 1997 by the Construction Project Information Committee (CPIC). Uniclass2 was developed after BIM to structure information and provide better integration between tables (CPIC, 2018). The latest version, Uniclass2015 was introduced by the National Building Specification (NBS) in 2015. Currently, it consists of 11 hierarchical core tables (Fig.1), each accommodating a different class of information required to support the Digital Plan of Work.

The core tables can be used to categorise information for costing, briefing, CAD layering, etc. as well as when preparing specifications or other production documents.

Fig 1: The current status of the classification tables, (Delany and NBS, 2018a)

Main core tables comprise:

(Delany and NBS, 2018a)

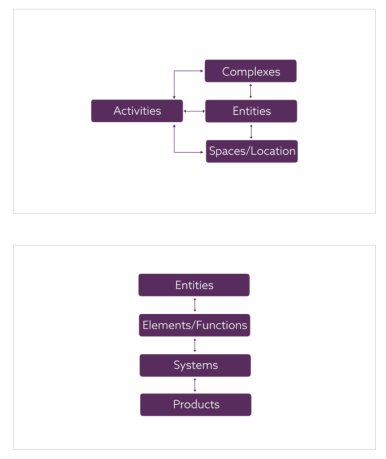

For detailed design and construction, ‘Entities’ are made up of ‘Elements’ which consist of ‘Systems’ that includes ‘Products’ (Fig.3). “Entities can also be described using the Spaces and Activities tables if required, and at the more general level, the Complexes table contains terms that can be thought of as groupings of Entities, Activities and Spaces” (Fig.2) (Delany and NBS, 2018a).

Fig3: Complexes, Entities, Spaces/Locations and Activities tables,

(Delany and NBS, 2018a)

Fig2: Entities, Elements/Functions, Systems and Products tables,

(Delany and NBS, 2018a)

Uniclass 2015 classification codes consist of 4-5 pairs of characters. The initial pair of the object code is made of letters and represents the table. The four following pairs are for groups, sub-groups, sections, and objects.

Each group of codes can accommodate up to 99 items, which allows plenty of scope for inclusion. An example from Uniclass2015 Table Ss Systems:

Overall, Uniclass 2015 has extended the scope of previous versions to provide a comprehensive system suitable for use by the entire industry for all stages in a project lifecycle, through consistent classification of buildings, engineering, landscape, and infrastructure. Compatible with BIM Level 2, it has also facilitated interoperability between different systems. Made up of 11 tables (Fig.1), it is compliant with ISO 12006-2, Uniclass 2015 system is compatible with BIM Level 2 and is adopted by the BIM Toolkit. In addition, although It includes only four core tables which describe different information that might apply to the same object, it is flexible enough to accommodate future classification requirements. In this respect, Uniclass2015 is better structured for BIM than other classification systems from other countries such as Omniclass (US).

2. Explain the different basic forms of procurement and the standard Construction Contracts available for each type and the roles and responsibilities defined and inferred within them.

Procurement, in general, refers to the process of obtaining a product or service. It is initiated by devising a project strategy, which entails weighing up the benefits, risks and financial constraints which attend the project, and which eventually will be reflected in the choice of contractual arrangements. In the construction industry, procurement refers to the way in which “the responsibilities for design and construction of a construction project are allocated, including the risks and responsibilities associated with the project” (JCT, 2018b).

There are several different procurement forms, each with its advantages and disadvantages. It is therefore important to select the procurement route that would be best suited for a particular project. This could be achieved through identifying the client’s key requirements, considering the experience and expertise of the project team as well as the other factors including value, size, and nature of the project.

There are three main procurement options, and the roles and responsibilities for each are as follows:

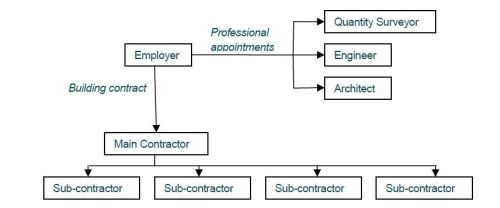

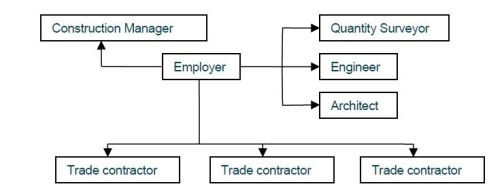

In the traditional approach, the design process is kept separate from the construction of the project. The employer appoints a team of professionals to design the project and a contractor to carry out the works (Fig.4). The appointment of the contractor is usually by competitive tendering on complete information. However, if required, a contractor may be appointed by negotiation based on partial or notional information (Davis et al., 2008). The traditional method, using two-stage tendering or negotiated tendering, is sometimes referred to as the ‘Accelerated Traditional Method’ – this is where the design and construction can run in parallel to a limited extent (JCT, 2018b). There are three types of contract under the traditional procurement method:

1. Lump sum contracts – where the contract sum is determined before construction starts, and the amount is entered in the agreement. The most common forms of traditional contract are the JCT (Joint Contracts Tribunal) Standard Building Contract, Intermediate Building Contract and Minor Works Building Contract.

2. Measurement contracts – where the contract sum is accurately known on completion and after re-measurement to some agreed basis. Standard Building Contract With Approximate Quantities (SBC/AQ)

Measured Term Contract (MTC)

3. Cost reimbursement – where the contract sum is arrived at on the basis of the actual costs of labour, plant and materials, to which is added a fee to cover overheads and profit. Prime Cost Building Contract (PCC)

Fig 4: Traditional Procurement, (Savage and Mondaq, 2015)

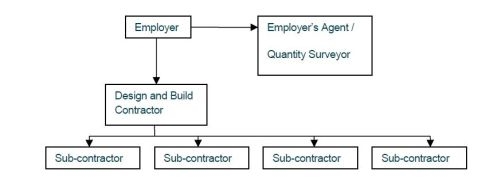

With Design and Build Procurement method, a contractor, who is often appointed through two-stage tendering, undertakes both the design and the construction of the work in return for a lump sum price (RICS, 2014).

Typically, employer’s professional team produce the employer’s requirements, which can range from a simple accommodation schedule to a fully worked out scheme design. Then, either the contractor employs his own professional team, or the employer’s professional team are novated to the contractor to meet the ’employer’s requirements. If the contractor uses external consultants, their identity should be established before a tender is accepted. “The client has control over the design elements included as part of his requirements, but, once the contract is let, has no direct control over the development of the contractor’s detail design” (Walker, 2017).

Types of contract for Design and build Procurement

1. Package deal or turnkey contract

2. Design and build contracts

3. Contractor’s design for specific elements only

Fig5: Design and Build Procurement, (Savage and Mondaq, 2015)

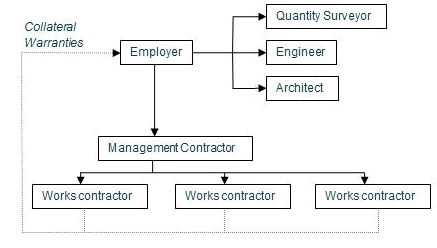

A method where overall design is the responsibility of the client’s consultants, and the contractor is responsible both for defining packages of work and then for managing the carrying out of this work through separate trades or works contracts (JCT, 2011).

Although there are several variants of management procurement forms, which include management contracting, construction management and design and manage, there are some subtle differences between these procurement methods. In the case of management contracting (Fig.7), the contractor has direct contractual links with all the works contractors and is responsible for all construction work (RICS, 2014). In construction management (Fig.6), a contractor develops and manages a programme for an agreed fee. His responsibilities include coordinating the design and construction activities and facilitating collaboration to improve the project’s constructability (Savage and Mondaq, 2015).

Types of contract for Management Procurement

1. Management contracts

2. Construction Management

3. Design – manage – construct

Fig 6: Construction Management, (Savage and Mondaq, 2015)

Fig 7: Management contracting, (Savage and Mondaq, 2015)

3. How might the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) affect architectural practices? What are the implications for, say, you as a start-up practice of one or two persons?

General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) is a legislative document by the European Union (EU) that was designed to unify data privacy laws in the EU, to strengthen data protection for individuals in the EU and to reform the way organisations across the region approach data privacy. From 28 May 2018, the EU GDPR will replace the Data Protection Directive 95/46/EC in the UK (Heath and RIBA, 2018).

GDPR is mainly concerned with the protection of the privacy of individuals about the processing of their personal data; making sure that organisations are “transparent and honest when collecting and processing personal data and respect that the individual owns and continues to control such use” (Lankhorst, 2017). Thus, GDPR will establish new responsibilities for those handling and processing personal data of EU residents and new rights for individuals across EU member states. As UK is still part of EU, any business operating in the UK has an obligation to update existing data rules to match them, so they are equivalent to the EU laws (NBS, 2018).

Although Compliant with new GDPR legislations is a concern mainly for large and multinational companies, architectural practices that hold and process personal data of and provide services to residents of EU countries will also have to comply with GDPR, irrespective as to whether or not the UK retains the GDPR post-Brexit. “GDPR makes ‘privacy by design’ a legal requirement, meaning building data protection into all new projects and services. This may require a data protection impact assessment to be undertaken” (Heath and RIBA, 2018).

If the practices fail to comply with GDPR, the supervisory authorities can either “(i) issue a warning or impose a temporary or definitive ban on processing personal data, or (ii) impose a fine up to EUR 20,000,000 or 4% of the total worldwide turnover, depending on the circumstances of each individual case, or both” (Martin and DBSdata, 2018). Such high penalties for breaches and non-compliance can be very damaging especially for start-up architectural practices providing services to EU residents. Thus, to avoid such high penalties, they must start thinking how they deal with personal, privacy-sensitive data.

In this respect, for a start-up practice, the best way to comply with GDPR is through gaining an understand GDPR’s scope and requirements. Then, they must be able to identify the personal data they hold about their employees, clients, and contractors etc. and regulate how this data is being stored, accessed, and used. For some organisations, such as public authorities or companies carrying out large-scale processing, GDPR requires the appointment of an independent Data Protection Officer. Although this would not apply to a small architect’s practice, someone internally should take responsibility for compliance (GDRP, 2018).

GDPR can be an opportunity to bring a small practice’s data practices up to contemporary standards, as it will allow UK-based practices to send and receive data within Europe freely. This will help protect their business from the risk of a breach while building trust in their customers.

Bibliography

ASPIN. 2018. Survey, Site & Ground Investigation [Online]. Aspin. Available: http://www.aspingroup.com/services/consulting/survey-site-ground-investigation [Accessed 06 April 2018].

CAMERON, J. 2016. Contingency Sum [Online]. Jane Cameron Architects. Available: https://janecameronarchitects.com/what-is-a-contingency-sum-3/ [Accessed 11 April 2018].

CLAYTON, C. R. I., MATTHEWS, M. C. & SIMONS, N. E. 2016. Site Investigation [Online]. University of Surrey. Available: http://tunnel.ita-aites.org/media/k2/attachments/public/1_Site%20Investigation%20by%20Clayton%20FREE.pdf [Accessed 04 April 2018].

CORE, J. 2018. Which sewer pipe is best – PVC or Clay? [Online]. Cotterill Civils. Available: https://www.cotterillcivils.co.uk/which-sewer-pipe-is-best-pvc-or-clay/ [Accessed 13 April 2018].

CPIC. 2018. Uniclass2 (Development Release) Classification Tables [Online]. CPIC. Available: https://www.cpic.org.uk/uniclass2/ [Accessed 1 April 2018].

CRAWFORD, C. B. 2016. Engineering Site Investigations [Online]. MIT. Available: http://web.mit.edu/parmstr/Public/NRCan/CanBldgDigests/cbd029_e.html [Accessed 07 April 2018].

DAVIS, P., LOVE, P. & BACCARINI, D. 2008. Building Procurement Methods [Online]. Curtin University of Technology

Western Australia Department of Housing & Work

Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology Available: http://www.mondaq.com/uk/x/383966/Government+Contracts+Procurement+PPP/Procurement+Options+For+Your+Middle+East+Project [Accessed 29 March 2018].

DELANY, S. & NBS. 2018a. NBS BIM Tool Kit Classification Tables [Online]. National Building Specification (NBS). Available: https://toolkit.thenbs.com/articles/classification#classificationtables [Accessed 28 March 2018].

DELANY, S. & NBS. 2018b. NBS BIM Tool Kit Classification: Technical Support [Online]. National Building Specification (NBS). Available: https://toolkit.thenbs.com/articles/classification [Accessed 28 March 2018].

GDRP. 2018. Art. 37 GDPR Designation of the data protection officer [Online]. GDRP. Available: https://gdpr-info.eu/art-37-gdpr/ [Accessed 02 April 2018].

GOULD, N. 2016. Standard forms: JCT, NEC3 and the Virtual Contract [Online]. Fenwick Elliott Available: https://www.fenwickelliott.com/sites/default/files/nick_gould_-_standard_forms_jct_2005_nec3_and_the_virtual_contract_matrics_paper.indd_.pdf [Accessed 11 April 2018].

GOV.UK. 2010. Community Infrastructure Levy: England and Wales [Online]. GOV.UK. Available: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukdsi/2010/9780111492390/pdfs/ukdsi_9780111492390_en.pdf [Accessed 15 December 2012].

GOV.UK. 2016. Building Regulations 2010: Approved document C, Site preparation and resistance to contaminants and moisture [Online]. GOV.UK. Available: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/431943/BR_PDF_AD_C_2013.pdf [Accessed 12 April 2018].

GOV.UK. 2017a. Town and Country Planning Act 1990 [Online]. GOV.UK. Available: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1990/8/part/IX/crossheading/acquisition-for-planning-and-public-purposes [Accessed Part IX Acquisition for planning and public purposes].

GOV.UK. 2017b. Town and Country Planning Act 1990: Temporary Stop Notices [Online]. GOV.UK. Available: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1990/8/part/VII/crossheading/temporary-stop-notices [Accessed 26 March 2018].

GOV.UK. 2018a. Guidance: Ensuring effective enforcement [Online]. Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government. Available: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/ensuring-effective-enforcement [Accessed 26 March 2018].

GOV.UK. 2018b. National Planning Policy Framework: Consultation proposals [Online]. Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/685288/NPPF_Consultation.pdf [Accessed 26 March 2018].

GOV.UK. 2018c. National Planning Policy Framework: Draft text for consultation [Online]. Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/685289/Draft_revised_National_Planning_Policy_Framework.pdf [Accessed 26 March 2018].

GOV.UK. 2018d. Planning enforcement – overview [Online]. GOV.UK. Available: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/ensuring-effective-enforcement#Temporary-Stop-Notice [Accessed 26 March 2018].

HEATH, D. & RIBA. 2018. GDPR – changes on the horizon for data protection legislation [Online]. RIBA. Available: https://www.thenbs.com/knowledge/are-you-ready-for-the-gdpr [Accessed 31 March 2018].

JCT. 2011. Deciding on Appropriate JCT Contract [Online]. JCT. Available: https://www.jctltd.co.uk/docs/Deciding-on-the-appropriate-JCT-contract-2011-Sept-11-version-2.pdf [Accessed 09 April 2018].

JCT. 2018a. Design and Build [Online]. JCT. Available: https://corporate.jctltd.co.uk/products/procurement/design-and-build/ [Accessed 09 April 2018].

JCT. 2018b. Traditional/Conventional [Online]. JCT. Available: https://corporate.jctltd.co.uk/products/procurement/traditionalconventional/ [Accessed 09 April 2018].

KCS. 2014. Choosing the Right Subsurface Drain Pipes [Online]. KCS. Available: http://kettyle.com/choosing-right-subsurface-drain-pipes/ [Accessed 13 April 2018].

LANKHORST, M. 2017. 8 Steps Enterprise Architects Can Take to Deal with GDPR [Online]. BizzDesign. Available: http://blog.bizzdesign.com/8-steps-enterprise-architects-can-take-to-deal-with-gdpr [Accessed 28 March 2018].

MARTIN, M. & DBSDATA. 2018. Data Protection Compliance Consultancy [Online]. DBSdata. Available: https://www.thenbs.com/knowledge/are-you-ready-for-the-gdpr [Accessed 02 April 2018].

MCNAIR, D. & PWC. 2011. Preparing the Employer’s Requirements for a Construction Project [Online]. PwC. Available: https://www.pwc.co.uk/legal/assets/investing-in-infrastructure/iif-10-preparing-employers-requirements-feb16-3.pdf [Accessed 09 April 2018].

NAYLOR, E. & WWT. 2007. Making Water Work: Clay beats PVC for green drainage [Online]. Water & Wastewater Treatment (WWT). Available: http://wwtonline.co.uk/info/WWTMagazine [Accessed 09 April 2018].

NBS. 2018. Are you ready for the GDPR? [Online]. National Building Specification. Available: https://www.thenbs.com/knowledge/are-you-ready-for-the-gdpr [Accessed 31 March 2018].

ODPM. 2005. TEMPORARY STOP NOTICE [Online]. OFFICE OF THE DEPUTY PRIME MINISTER. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/7671/circulartemporarystop.pdf [Accessed 30 March 2018].

RICS. 2014. Building contracts in the UK [Online]. The Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS). Available: http://www.rics.org/uk/knowledge/glossary/building-contracts-in-the-uk/ [Accessed 16 February 2018].

SAVAGE, D. & MONDAQ. 2015. UK Procurement Options [Online]. Mondaq. Available: http://www.mondaq.com/uk/x/383966/Government+Contracts+Procurement+PPP/Procurement+Options+For+Your+Middle+East+Project [Accessed 29 March 2018].

STEEDS, J. E., SLADE, N. J. & REED, M. W. 2018. TECHNICAL ASPECTS OF SITE INVESTIGATION, VOLUME II (OF II) TEXT SUPPLEMENTS [Online]. Environment Agency. Available: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20140328173019/http://cdn.environment-agency.gov.uk/sp5-065-tr1-e-e.pdf [Accessed 07 April 2018].

VAN TUBBERGH, C. 2012. The effect of soil conditions on the cost of construction projects [Online]. University of Pretoria. Available: https://repository.up.ac.za/bitstream/handle/2263/41011/Van%20Tubbergh_The%20effect%20of%20soil%282012%29.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [Accessed 04 April 2018].

WALKER, D. 2017. Law and Contracts [Online]. Prezi. Available: https://prezi.com/j3vedtag0gz5/law-and-contracts/ [Accessed 14 April 2018].

You have to be 100% sure of the quality of your product to give a money-back guarantee. This describes us perfectly. Make sure that this guarantee is totally transparent.

Read moreEach paper is composed from scratch, according to your instructions. It is then checked by our plagiarism-detection software. There is no gap where plagiarism could squeeze in.

Read moreThanks to our free revisions, there is no way for you to be unsatisfied. We will work on your paper until you are completely happy with the result.

Read moreYour email is safe, as we store it according to international data protection rules. Your bank details are secure, as we use only reliable payment systems.

Read moreBy sending us your money, you buy the service we provide. Check out our terms and conditions if you prefer business talks to be laid out in official language.

Read more