AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL STUDY OF EATING PERSPECTIVES, MEAL COMPOSITION, AND FOOD CHOICES AMONG DIVERSE STUDENT POPULATIONS

ABSTRACT

My thesis explores the factors that shape or reinforce international college students’ perceptions of food. This research not only examines how cultural values affect individual nutrition and maintenance of eating behaviors, it also addresses the extent to which accessibility impacts eating behaviors. Notably, the research endeavor uses the concept of dietary habitus as an underlying directive mechanism for study. This study finds that most students experience a reduction in their fruit and vegetable intake. Another finding suggests that international students eat healthier and are more structured in comparison to domestic students if they hybridize their dietary habitus. Research findings also suggest that most participants perceive food on campus to be both equally healthy and unhealthy, with limited accessibility to national cuisines and affordable healthy foods.

Differences Between the Standard American Diet and Traditional Foods

CHAPTER TWO: LITERATURE REVIEW

CHAPTER THREE: RESEARCH SETTING AND METHODS

CHAPTER FOUR: QUANTITATIVE DATA ANALYSIS

Consumption of National Cuisines

CHAPTER FIVE: QUALITATIVE DATA ANALYSIS

Social Support Networks and Resistance to Dietary Changes

Accessibility and Changes to Eating Patterns

Food Preferences as Resilience

Carbohydrates and Dairy Intake

Structured and Unstructured Meal Times

Consumption of Traditional Food Items and National Cuisines as Resistance

National Cuisines Versus American Cuisines

Resistance to Unhealthy Eating Behaviors

Meal Times and Structured Eating

ON CAMPUS DINING SUVEY 2016-2017

APPENDIX B: INTERVIEW QUESTIONS

Interview Questions for M.A. Research

APPENDIX C: RECRUITMENT INVITATION

APPENDIX E: DEFENSE ANNOUNCEMENT

APPENDIX F: IRB APPROVAL LETTER

Figure 1: Past and Current Consumption of Fruit Varieties by Domestic Survey Sample

Figure 2: Past and Current Consumption of Fruit Varieties by International Survey Sample

Figure 3: Past and Present Consumption of Vegetable Varieties by Domestic Sample

Figure 4: Past and Present Consumption of Vegetable Varieties by International Sample

Figure 5: Past and Present Consumption of Vegetable Varieties by Interview Sample

Figure 6: Past and Present Consumption of Fruit Varieties by Interview Sample

Table 1: Ethnicity, Age, Sex, and Academic Career of Interview Samples

Table 2: Types of Food Varieties and Number of Illustrative References

Table 3: Age, Sex, Ethnicity, and Academic Career of Survey Subjects

Table 4: Interview Sample’s Categorizations of Health and Nutrition

Table 5: Interviewees’ Fruit Intake and Differences Since Attending University

Table 6: Interviewees’ Vegetable Intake and Differences Since Attending University

Table 7: Interviewees’ Past and Present Consumption of Healthy Protein Products

Table 8: Interviewees’ Past and Present Consumption Types of Unhealthy Protein Products

Table 9: Interviewees’ Past and Current Consumption of Healthy Dairy Products

Table 10: Interviewees’ Past and Current Consumption of Unhealthy Dairy Products

Table 11: Interviewees’ Past and Current Consumption of Healthy Carbohydrates

Table 12: Interviewees’ Past and Current Consumption of Unhealthy Carbohydrates

Perhaps more so today than ever before, college students are confronted with a wide range of on campus dining options that are no longer limited to the traditional cafeteria favorites of breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Student unions across the country now feature well-known fast food eateries including Chik-fil-A, Qdoba, and Subway alongside more conventional dining hall facilities with their familiar tray service and buffet-style selections. Whether at private or public institutions of higher learning, this expansion in eating options increases convenience but also presents new challenges to undergraduates who are living away from home for the first time. Alakaam et al. (2015:104) report that many college freshmen, international students, and others who are living away from home for the first time are particularly at risk for developing health problems associated with unhealthy eating practices. They identify over/under eating, stress induced eating, and nutritional deficiencies as outcomes of limited access to healthy food options and the overall university experience.

On campus dining choices are influenced by various social, cultural, economic, geographical, political, and religious factors. Increased understanding about what compels university students to choose certain campus dining options over others can be approached from various social scientific perspectives as well as through the lens of cultural anthropology. Essential to the aims of my thesis is the idea that people consume identity through food. Of specific interest at the University of Central (UCF) is how meal compositions for first and second year Asian international college students change over time from their everyday local diets. Everyday local diet refers to what respondents commonly consume in their home country such as national cuisines, and dishes eaten inside and outside of the home.

Students who commonly eat traditional diets and national cuisines may be vulnerable to widely available convenience cuisines when they enter a campus food environment for the first time as they are exposed to various unhealthy high calorie meals. According to Alakaam et al. (2015:109) on campus dining typically features buffet-style meals, fast food, and there are comparatively more American food choices. Brewis (2012) finds that cost-efficient cuisines of this variety are primarily marketed towards children, adolescents, and young adults. To best prevent the rising prevalence of overweight students it is critical to identify and examine at risk periods of weight gain and development of unhealthy eating behaviors. Difficulties transitioning from high school to university have been distinguished as a high-risk period for students. This move to higher education generates consequences for many young adults as they relocate away from familiar surroundings, attain more independence, and establish new relationships. This transition might be followed by modification or abandonment of formerly held routines and integration of new dietary habits (Deforche et al. 2015).

Consequently, it is often difficult for university students to negotiate the campus foodscape to find well-balanced and nutritious meals. Furthermore, the U.S. currently maintains the world’s highest proportion of international students, accounting for approximately 17 percent of all international students worldwide (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development [OECD] 2013). The significant number of international students creates added pressure for universities to meet the dietary demands of often ethnically diverse populations. Other sources maintain that it warrants further discussion, emphasizing that in many academic institutions growing numbers of international students are enrolled and contribute to the cultural diversity of student populations in the U.S. Researcher Behjat Sharif (1994:264) maintains that “there has not been sufficient investigations to uncover the nature of their health-related problems and unique conditions influencing the health of international students.” Notwithstanding, the deficiency of academic literature available suggests that international students face problematic periods of adjustment which can adversely affect their health. Recent student protests at Oberlin College draw attention to many criticisms of dining hall food. Students describe some of the food as “culturally insensitive” or lacking in fresh or traditional ingredients (Mejia 2015:1). Cultural student organizations’ demands for more culturally appropriate food items met a positive response from dining services who vowed to alter menu items.

To address such considerations, my thesis focuses on the eating behaviors and meal compositions of diverse student populations at UCF, the nation’s second largest institute of higher learning with an estimated enrollment of approximately 60,000 students (2014-2015 Common Data Set 2015). Moreover, UCF has a sizeable number of international students who comprise 2.5 percent of the student population. Considering the large proportion of Asian international students, it is pertinent to investigate the challenges of eating in a university environment, and how the population modifies food choice. Furthermore, per the International Affairs and Global Studies ([IAGS] 2014) website there are 2,128 international students attending UCF. A total of 450 Southeast Asian and East Asian international students currently attend UCF which accounts for approximately 21 percent of the total amount of registered international students. Compared to other international populations attending the university there are more Southeast/East Asian international students enrolled. Specifically, the research endeavor focuses on East Asian and Southeast Asian students who have lived in the U.S. for a period of six months to two years. Given the varied demographic composition of UCF’s student body, questions arise about what if any differences emerge in how distinct undergraduate cohorts both negotiate the food choices of on campus dining and compose their daily meals. To determine what role, if any, nationality plays in these considerations, I compare the food and meal behaviors of a select population of international students at UCF.

In concrete terms, my thesis addresses the following research questions: (1) How do Asian international students at UCF currently construct meals?; and (2) how do their current on campus food choices compare with what they typically ate in their country of origin?

Distinctions between the composition of standard American meals and those eaten within traditional Asian diets are numerous (Alakaam et al. 2015, Amos and Lordly 2014, Choi et al. 2015). Alakaam et al. (2015) and Amos and Lordly (2014) argue that not only are many of the foods offered on campuses like UCF’s unfamiliar to international students it is also sometimes difficult for Asian international students to distinguish between healthy and unhealthy foods. For example, Alakaam et al. (2015:110) also find that most of international students reported eating traditional meal compositions before moving to the U.S. Specifically, students defined traditional foods as “fresh prepared, simple, and basic, such as meat, eggs, fish, beans, vegetables, fruit, seeds, and milk.” Furthermore, international students in their study (Alakaam et al. 2015) report that they do not eat a lot of fast food in their home country due to the high cost of convenience/processed foods compared to relatively inexpensive fresh foods. Accordingly, I hypothesize that if the sample population reports eating meals composed in similar ways to what they commonly ate at home, they will continue to eat healthy, modify their diets, and develop fewer health problems compared to their domestic counterparts.

In addressing these research questions, I utilize a constructivist “grounded theory” in combination with ethnography to analyze data. According to Ralph et al. (2015:66-67) grounded theory is a useful concept in qualitative approaches, allowing researchers to code and categorize emerging themes. The thick description provided by ethnography is complimentary to grounded theory generation since both generally use naturalistic styles of inquiry such as participant observation and interviews. Additionally, socio-cultural researchers view ethnography as a viable way to generate contextualized understandings of the “ways in which consumers buy and use specific items,” while simultaneously providing generalizability to their insights. Similarly, the methodological approach of grounded theory allows for the generation of “substantive theories of behavior,” and creates a way to cross-validate findings (Pettigrew 200:259).

Moreover, I also rely on Pierre Bourdieu’s (Sato et al. 2016:174) concept of habitus to address how acquired schematic perceptions (i.e. cultural beliefs and practices) of meal construction influence individual preferences to eat unhealthy/healthy foods. Notably, meal compositions among Asian international students are an embodiment of their reproduced cultural values, including social and psychological processes which regulate perceptions and actions. What students do in their daily routines influences their decisions to eat specific items and is ultimately socially reinforced in a recursive interplay between the individual and structural “agency” through time (Smith 2017:103).

For instance, international students’ food habits are constructed in their home country and are a product of social conditioning. Taking their preconceived notions about food with them, students incorporate their emic worldview into new environments. Habitus triggers reactive behaviors and facilitates perceptions in the context of a specific field or circumstance. Within the context of the on campus dining options, students can utilize individual agency orplasticityby altering what they previously consumed (Smith 2017:103-104). Accordingly, one’s food habitus can be modified or hybridized, especially when entering a new foodscape.

According to Tam et al. (2010) and Cantarero (2009), nutritional perspectives are specific to one’s culture and preference is often contingent upon factors such as ethnicity, country of origin, and acculturated/enculturated ideologies about health and food quality. I argue that homogenization of meal composition may be related to factors associated with globalization and acculturation. Globalization is used to describe the process of organizing nations and people into a greater global community which can affect culture, politics and economics. Acculturation describes the process of culture change through external forces, and contact between cultures. Both are factors involved in cultural hybridization or “transculturation” and can impact a variety of behaviors and attitudes which include: taste preference, sensory characteristics, availability, convenience, cognitive restraint, and cultural knowledgeability (Alakaam et al. 2015, Amos and Lordly 2014).

To date, relatively few anthropological studies have emerged which comparatively assess the food choices and meal compositions of international and domestic university students in terms of nationality, residency status, and campus food environment. Furthermore, previous studies do not address the specific features which comprise the everyday local diets of international students pre- and post-migration or the food choices of domestic students prior to and while attending university. In the past, anthropologists have examined the sociality of consumption patterns found in different cultural groups and populations to determine how dietary preferences affect individual health, status, and socio-political relationships (Brown et al. 2010, Binge et al. 2012, Cantarero 2009, and Dufour et al. 2013). Additionally, sociologists (Choi et al. 2011, Cantarero 2009), evolutionary scientists (Brewis 2012), and others working in fields of health and nutrition (Alakaam et al. 2015, Deforche et al. 2015, Gorgolhu et al. 2012, Hang 2015, Moreira et al. 2005, Quick and Byrd-Bredbenner 2013, Sampaio et al. 2015, and Tam et al. 2010, Valladares et al. 2016, and Wang et al. 2008) have examined the meal composition and social and biological implications of consumption.

Public awareness regarding the negative effects of convenience foods on health has encouraged dining institutions in public and private education facilities to incorporate more diverse dining options (Binge et al. 2012). Improvements in food choices and culturally sensitive cuisines may generate improvements in individual nutrition. According to Brewis (2012:1-2), obesity rates in the U.S. have doubled in just one generation. The development underlies current concerns about the nutritional content and food quality of student eating options. For example, Sampaio et al.’s (2015:66) anthropometric and nutritional assessment of college students finds that the domestic college campus population consumes a disproportionately high amount of fats and sugars compared to fruits and vegetables. A critical examination of student eating habits and meals helps clarify why these disparities occur in diverse student populations.

Like Sampaio et al. (2015) Gorgulho et al. (2012:806-807) also address the significance of college students’ food choices. Specifically, they examine the students’ intake of sugars, carbohydrates, and fats relative to grains and vegetables/fruit. Fruits and vegetable consumption was reported as being lower if college students were employed an average of 30 hours a week. This may account for a greater consumption of convenience foods by university students since it can be challenging for students to find time to prepare healthy meals. Examining the role that stress and work specifically have on student diets may yield important differences on how students eat at home versus what they eat at school.

Deforche et al. (2015:1-2) examine changes in weight, activity and eating behaviors of university students. Specifically, they explore the phenomenon colloquially known as the “freshmen 15,” a period where students typically gain weight their first year of attending university. The researchers provide anthropometric and BMI data which indicate levels of health before entering university. Their data shows that college freshmen on average consumed less fruits and vegetables upon entering college and confirms previous studies (Sampaio et al. 2015, Gorgulho et al. 2012). Additionally, their study examines how an increase in sedentary lifestyle choices such as watching television, surfing the Internet, studying, or playing videogames, as well as unhealthy dietary decisions can increase weight gains. The researchers admit that their study is unable to fully investigate other factors that may lead to changes in BMI including recent dieting, meal frequency, snacking, meal location, and skipping meals (Deforche et al. 2015). My research seeks to address these gaps and effectively explore variations in meal frequency, meal location, and other dietary behaviors as they relate to culture and campus food environments.

Drawing upon the works of nutritional and sociocultural anthropologists, my research findings also elucidate attitudes towards food accessibility, meal composition, and processes of globalization. My thesis is not the first to focus on college age students, for example, Matejowsky (2009) examines Filipino college students, studying the effect of corporate fast food’s influence on dietary choices and student nutritional perspectives. Stockton and Baker (2013) analyze the changing opinions and attitudes of Midwestern college students towards fast food by exploring how age and gender impacted preference. They find that caloric deterrents are the most prolific factors in determining food choices which may explain avoidance of convenience foods by certain students.

Another issue effecting student nutrition are the dining halls themselves. Binge et al.’s (2012:123-124) anthropological study examines the role of campus foodservice in the lives of Chinese students. Although not set in the U.S., their study is relevant since it explores some of the challenges experienced by students in an unfamiliar foodscape. They find that most students viewed on campus dining facilities as being nutritionally deficient or lacking in variety. Their qualitative research suggests that universities should offer more diversity in their menu items and update their menu items so students do not become tired of the same things being served repeatedly. Students also report a desire to have adequate accessibility to balanced nutrition.

Overall, Binge et al.’s (2012:141) anthropological investigation into student diets finds that dining halls did not satisfy student’s needs. They (Binge et al. 2012:121) go on to say, “we have found that catering was to satisfy a biological need of students but it not only influenced student health directly and affected spiritual outlook, pleasure degree and learning outcomes, which influenced the overall satisfaction towards the school.” Additionally, they report that dining halls did not fulfill students’ needs. Their analysis of interviews finds that their student sample is not satisfied by campus food service which affects their accessibility to healthy foods. More than half the students report that on campus food service affects individual nutrition. Other students felt that on campus dining led to health problems because it did not offer choices; approximately 40 percent of the students report that there “was no reasonable nutrition” in the food (2012:131)

Furthermore, food scientists (Moreira et al. 2005:229) suggest that university students exhibit various degrees of restraint which considerably affects their fruit and vegetable intake. Cognitive dietary restraint refers to a process where individuals closely monitor their food intake to achieve desired results. Compared to low-restraint individuals, high restraint individuals tend to eat structured meal compositions to lose weight or maintain a healthy and balanced diet. High restraint individuals typically ate less starchy foods while low restraint participants engaged in higher caloric diets. The extent which “restraint” and structure in meal composition are culturally regulated would benefit from an anthropological investigation to determine how these two concepts are related.

Dietary habits can have far reaching effects aside from weight losses and weight gains. Working within the discipline of food science, Valladares et al. (2016:699) suggest that students eating habits are associated with their academic performance. Their survey of university students examines the role of dimensions or eating behaviors and their effect on cognitive processing. Like Moreira et al. (2005) they argue that students who practice high levels of cognitive restriction will have better academic performance compared to students who have a higher propensity for uncontrolled and emotional eating. Their study highlights that drinking habits, food choices, food quality, cooking methods, and portion sizes are facilitated by learned, cultural experiences. They conclude that “behavioral disinhibition” may be correlated to BMI, which then adversely affects academic performance (2016:703).

Their research (Valladares et al. 2016) is relevant to my study since I am measuring similar variations in eating behaviors such as levels of cognitive restraint, malnutrition, and over-nutrition and the impact they may have on pre-established dietary habits. Their research reveals that there was a positive correlation between grade point averages and eating behavior in female university students.

Additionally, Quick and Byrd-Bredbenner (2013:53) examine college students to determine what individual and social factors influence eating habits. They report that respondents are influenced by factors other than restraint such as depression, anxiety, and obsessive compulsive disorders. Their research highlights why meal compositions may change due to environmental and internal stressors.

Besides studies which predominately focus on domestic student diets, Alakaam et al. (2015:104) investigates the dietary acculturation of international students. They identify what factors influence deviations in food preference. They find that changes in students’ “food environment, campus environment, religion, and individual preferences” may result in things like weight gain, higher cholesterol, increased blood pressure, higher blood glucose levels, and select mental problems such as depression and anxiety. Specifically, their incorporation of the concepts of “traditional food,” “food environment,” and “campus environment” highlight the relative significance of location and atmosphere in facilitating dietary choices. Their study (Alakaam et al. 2015:105) is helpful since they can define traditional foods as a “food with particular characteristic in term of the use of raw ingredients which differentiate it from other processed or convenience food.”

Moreover, Tam et al. (2010:979) addresses how the dietary acculturation of second generation Asian-Americans is a result of culturally facilitated meal hybridization. The researchers analyze the diets of Los Angeles area Korean college students and compared their diets to those of older Koreans living in the same region. Notably, they compare how enculturation/acculturation and processes of Westernization affect the food choices of different demographics. Their findings suggest that college age Koreans are more likely to consume dairy, calories, and carbohydrates than older generation Koreans. Significantly, they find that students who still lived with their parents and grandparents were more likely to consume more traditional Korean foods. Their research reveals that social forces act as mediators in combining Eastern and Western food ideologies and the overall gravitation towards the “Americanization” food preference.

Similarly, Wang et al. (2008:756) examines the caloric and nutritional intake of Taiwanese medical students and American college students in Los Angeles. They find that both groups fail to meet their suggested daily requirements of fruits and vegetables which may be related to their respective food/campus environments. Notably, they suggest that the native Californian population consumes more fruits and vegetables compared to Taiwanese students. The Taiwanese sample population appears to eat more rice and simple grains. Additionally, the Los Angeles sample population generally eats less meat, beans, and grains which may reflect American dietary habits and meal composition.

Correspondingly, Amos and Lordly (2014:59) examine cross-cultural research on international students and the process of acculturation as it relates to food. Unlike traditional approaches they use the idea of “photovoice,” to collect students’ nutritional perspectives. Moreover, the study (Amos and Lordly 2014:59) finds “seven themes related to the significance of food in acculturation were revealed: the paradox of Canadian convenience, the equation of traditional foods with health, traditional food quality and accessibility, support networks, food consumption for comfort, ethnic restaurants, and the exploration of non-traditional foods.” Ultimately, they conclude that there remains a pronounced need among international students to utilize food to satisfy emotional and physical needs in a new environment. Nonetheless, unequal access to foods commonly consumed before university attendance in Canada remains an issue for some international samples more than others. For instance, Chinese students report having easier access to traditional diets compared to Saudi Arabian students. Differential access to healthy foods is a disparity I explore in my research endeavor.

Additionally, Pan et al.’s (1999:54-57) research discusses the vulnerability of Asian populations over other international populations. They find that Asian students intake of fats, salty and sweet snack items, and dairy products increased overall. Their study concludes that there were substantial decreases in the consumption of meat and meat alternatives, as well as fruits and vegetables. Findings indicate that although Asian students ate out less often than American students, when they did, they were more likely to choose American convenience foods. These types of studies highlight the challenges that Asian international students face in negotiating a vastly different food environment.

In a similar research study to Amos and Lordly (2014), Brown et al. (2010:202) explore the cultural meanings attached to food. Working within the parameters of nutritional anthropology, they examine the role of food in the lives of international graduate students experiencing changes in their dietary habits resulting from relocation to foreign university foodscapes. Their study highlights the phenomenon of “culture shock,” which entails “anxiety that results from losing the familiar signs and symbols of social intercourse and substituting them with other cues that are strange” (2010:202). They examine emotional and sensory differences between home and international foods. Moreover, they delve into the support networks created when students eat national dishes together. Like other studies, they focus on how cultural transition can lead to changes in BMI and unhealthy eating behaviors. Their research finds that students preferred to hybridize their meal composition to include home-made national dishes. International students felt that national dishes were not only healthier, but better tasting as well. Overall, students perceived local food as less tasty, and less nutritious overall, containing higher levels of sugar and fat. Their concluding remarks urge universities to address the nutritional well-being of international students in order to better assist incoming cohorts with the transition process as well as to improve upon the quality and nutritional accessibility of healthy foods on campus.

Furthermore, a study by Hang (2015:758) explores the problems facing Chinese international students attending American universities and how they discern potential health risks associated with convenience foods and cuisines. Using the Risk Information Seeking and Processing (RISP) model Hang investigates the role of risk assessment and self-efficacy in avoidance behaviors in Chinese students (2015:760). He claims that health concerns are a major deterrent for the sample population to make balanced food choices. Specifically, his study suggests that “those who come from a foreign country and who have not been exposed to a lot of information about the hazards of consuming these foods become a more vulnerable group than those who were born and socialized into the American food marketing environment” (Hang 2015:765).

The previously discussed studies are relevant to my thesis research as they help highlight differences in food choices of first year domestic students and first year international student populations. Studies focusing specifically on international students (Alakaam et al. 2015, Brown et al. 2010, Amos and Lordly 2014, Hang 2015, and Pan et al. 1999) reveal some of the obstacles foreign students are faced with in new foodscapes. Additionally, their studies demonstrate the importance of national cuisines in international student diets. Their data are useful in differentiating between Americanized and more traditional food items and behaviors. Furthermore, Alakaam et al.’s (2015) study demonstrates the common dietary trends of both American and traditional dietary habits. Research endeavors focusing on domestic college populations (Binge et al. 2012, Deforche 2015, Gorgulho et al. 2012, Moreira et al. 2005, Quick and Byrd-Bredbenner 2013, Tam et al. 2010 Sampaio et al. 2015, Stockton and Baker 2013, and Valladares et al. 2016) explain the dietary habits of students in their respective domestic environments. Tam et al. (2010) is particularly useful in explaining dietary acculturation and hybridization of food choice. Moreover, Wang et al. (2008) compares the food choices of domestic American college students to those of Taiwanese students, highlighting the differences in consumption behavior. Overall, the studies provide valuable insights into food habitus, food choice globalization, and dietary acculturation over time.

To compile a relevant body of data, I employ a variety of methodological techniques. These include: (1) participant observation, (2) questionnaire survey, (3) interviews. The three ethnographic techniques are essential because they provide different types of contextual information in diverse research settings. These types of techniques are highlighted by anthropologists as essential to the identification and analysis of emergent themes (DeWalt and DeWalt 2011:3, Fetterman 2010).

All the potential respondents were approached on UCF in the following locations: GLOBAL UCF, the two dining halls, the Student Union, the John T. Washington Center, and the John C. Hitt library. Prospective respondents were asked if they would like to participate in a research study on student diets and cultural perceptions. All 25 interviews were conducted over a period of five months; from to August to December 2016. The five semi-structured interviews, and 20 informal interviewees were recruited through the dining halls, and with the assistance of UCF GLOBAL. The survey questionnaire was administered both online and to students at various campus locations.

Considering the UCF area is home to a wide variety of restaurants and dining institutions, nonetheless, students may find themselves saturated with convenience foods and fast-casual eateries that make it difficult to maintain a healthy diet. A simple web search reveals that within a two-mile radius of UCF campus there are at least 15 fast food and fast-casual establishments. The widespread availability of high-fat, low-nutrition foods served by such quick-service eateries in a relatively small spatial proximity is the subject of recent scientific inquiry. Differing from the idea of a “food desert,” the term food swamp has emerged in academic literature. This concept often refers to an area that contains high proportions of calorie-dense, high-fat and high-sugar food items (Bridle-Fitzpatrick 2015:2). In addition to the stress of moving into a new community, food swamps can make it challenging for students to secure healthy, nutritious meals.

UCF’s campus foodscape offers slightly more variability in terms of the cuisines offered. There are some 25 places to dine on campus (UCF Campus Map) including two major dining halls: 63 South and Knightro’s. The smaller of the two facilities is Knightro’s which is located near the Towers residential student housing, CFE Arena, and Memory Mall. It is also a short distance away from the Towers and Lake Claire dormitories. The larger of the two dining halls is 63 South which is located near the Libra and Apollo dormitories in Ferrel Commons. It is also a short distance from the Math and Sciences building, the Reflection Pond, Technology Commons, the CREOL building and the Harris Engineering Building. The following sub-chapters review each dining area specifically.

The dining halls at 63 South and Knightro’s are facilities that offer UCF students an assortment of cuisines to students. Both locations are usually busy with student and faculty diners. Upon entering the dining hall, students are met with a variety of options from which to choose from. The dining areas feature different selections that are subdivided into distinct stations. “Chef’s Plate” is one of the featured stations. It typically serves a meat protein, starch, vegetable, and occasionally a carbohydrate like rolls or flat bread. The “grill” station usually serves items such as: hamburgers, hotdogs, turkey burgers, cheese steaks, chicken nuggets, grilled chicken sandwiches, Montecristo’s, corn dogs, and French fries. The “sauté” station often features ethnic cuisines as well as chicken, beef, and pork meats usually combined with a pasta or rice component. The station includes self-serve vegetables mixed in with the pasta and accompanied by marinara, alfredo, cheese, or broth based sauces.

The “deli” station serves sandwiches and a variety of side salads (e.g. potato salad, macaroni salad, seafood salad, tuna salad, or chicken salad), along with pickles, tomatoes, lettuce, onion, and cheese. The breads offered by the deli range from wheat and white hoagies rolls, to wraps and flatbreads. The students have the choice to eat ham, turkey, and chicken on their sandwiches. “Vegan” and “pizza” stations are located adjacent to the deli. The vegan station serves dishes with side items including rice, couscous, rice noodles, barley, quinoa, and fresh vegetables. The menu items are usually mixed in with a vegetable broth or curry. The pizza station has a set daily menu, featuring cheese pizza and pepperoni pizza. There is some variety in the specialty pizza which usually is a vegetarian pizza, calzone, or flatbread pizza that is topped with meat, sauce and cheese.

The “espresso” and “dessert” stations not only serve coffee drinks, tea, hot chocolate, and specialty drinks that are available upon request, they also offer a variety of desserts which rotate daily. Always available are sugar, chocolate chip and vegan oatmeal cookies. The desserts range from molten lava cakes, brownies, cobblers, pies, and cakes to rice crispy treats and muffins. The espresso station is attached to the cereal dispensers, offering popular cereals like Lucky Charms, Cheerios, Golden Grahams, and a gluten-free option among others.

The salad section is located near the center of the dining hall. Students can choose from green romaine lettuce, ice berg lettuce, and spinach. The additional items students can choose from options which include: carrots, tomatoes, cucumbers, green peppers, corn, garbanzo beans, quinoa, barley, shredded cheddar cheese, yogurt, honey dew melon, cantaloupe, black beans, canned pineapple, canned peaches, and different types of salad dressing. In addition, bagels, sliced white bread, and sliced wheat bread are offered alongside marmalade, jelly, and plain cream cheese. The students can also choose to top their salads with dried cranberries, sunflower seeds, croutons, and dried egg noodles.

Unlike other on campus eateries, the dining halls experience a breakfast, lunch, and dinner rush as opposed to just one time of day which is typical for restaurants in the Student Union. The breakfast rush usually begins around 8:00am, lasting for approximately two hours, the lunch rush starts at 11:30am and lasts until about 3:00pm. For dinner, the busiest times are between 5:30pm and 9:00pm. The availability of fresh fruits and vegetables at both dining hall locations offers variety whereas other on campus dining locations typically do not feature these items. Conversely, the dining halls offer convenience foods, and high-calorie options. The ratio of healthy to unhealthy food items are discussed in more detail in Chapter Five.

The Student Union offers an array of dining choices for UCF students and faculty. Featured eateries include Knightstop & Sushi, Pita Spot, Subway, Corner Café, Domino’s, Asian Chao, Huey Magoos, Café Bustelo, Qdoba, Nathan’s, and a Chili’s Grill and Bar. These restuarants are usually very busy during lunch and dinner hours. The lunch rush occurs between 11:30am and 3:00pm. While the dinner rush typically starts at 5:00pm and lasts until about 7:00pm.

The John T. Washington Center or “Breezeway” is another dining area where students can eat breakfast, lunch, and dinner. It is generally a very active social space for students; a place for friends to eat and relax in between classes. The two main eateries located in the “Breezeway” are Chik-fil-A, and a Starbucks located inside of the UCF bookstore.

Additionally, located on UCF campus near the CFE Arena are quite a few dining options including: Knightro’s are Einstein’s Bagels, Kyoto Sushi & Grill, Burger U, and Domino’s. Einstein’s Bagels primarily serves bagels, muffins, and sandwiches. Domino’s menu includes, pizza, salad, pasta bowls, bread sticks, and salads. Kyoto features largely Americanized versions of traditional Asian cuisines such as rice and meat dishes and noodles. Burger U primarily serves burgers, fries and other types of convenience foods. Smoothie King offers students blended smoothie options as well as energy and assorted meal replacement bars.

Participant observation is a key aspect of my thesis research since it enabled me to subtlety record and collect descriptive data on large groups of people. DeWalt and DeWalt (2011:123-126) maintain that participant observation provides “inherently emic views” and “records of prolonged activity,” which are in this case associated with eating behaviors. Additionally, participant observation allows for multiple opportunities to observe students as they eat and note their reactions to food in a naturalistic setting. From July to December 2016 I observed students’ eating behavior across UCF, including locations within campus dining halls, the Student Union, Breezeway, and other areas.

Besides meal locations, I documented whether or not those observed returned for multiple portions of the same food item. This information suggests preference or meal satisfaction. This allowed me to record if students visually/verbally expressed satisfaction/dissatisfaction with their food choices; specifically, whether students consumed or disposed of certain food items in the trash. Furthermore, recording the specific meal components; including how long individuals spent eating food items and the approximate time students spent dining overall. During my observations and interviews, I employed the technique of active listening which requires the undivided attention from the investigator. Active listening is an important part of anthropological research since it allows for the detection and assessment of “key events” and dialogue (DeWalt and DeWalt 2011:183). Participant observation notes were hand-written in notebooks and later manually transferred into a digital format for analytical coding.

Formal and informal interviews also played an essential role in data collection about student eating behaviors. Ethical approval to continue this research came from the UCF’s Internal Review Board. Moreover, all interviewees were offered financial compensation; one dollar, for their time. I recruited 25 interviewees to participate in interviews guided by questions approved by the UCF IRB (See Appendix D). All participants were briefed regarding the scope and purpose of the study and informed that their participation was completely voluntary. Correspondingly, they were given informed consent forms to review and keep for their records. Respondents were not required to sign consent form since the study posed minimal risk and their identity kept private using pseudonyms. From the 25 interviews conducted, five consisted of semi-structured recorded interviews and 20 consisted of unrecorded semi-structured interviews. I interviewed seven domestic students and 18 international students in total. Out of the 25 interviewees, 10 are female and 15 are male.

Moreover, a dual methodological framework remains a useful tool to collect and organize context-driven information (Ralph et al. 2015:1-2). I examined students, recording and discussing what respondents consumed day to day. I observed the meal compositions of students from varying ethnic backgrounds on a weekly basis for a period of six months. To clarify, meal composition describes the nutritive substances found in food and the term refers to a meal’s structure and the individual components. Besides observing and interviewing international students from the research populations that eat many of their meals on campus, I also implemented a “photo-voice” approach to discern how food habitus affects their perceptions of meal structure, food quality, and convenience within sample populations (Amos and Lordly 2014:59). Photo-voice employs the use of laminated photographs depicting various traditional and non-traditional foods items. The approach created an effective way to help students construct what they commonly consumed before college in addition to what their current diet.

Pseudonyms are used to protect the identity of my interviewees. Alyssa (Subject 1) is a U.S. citizen who lives on campus. Phillip (Subject 2) lives on campus in a shared dormitory and has been residing in the U.S. for almost a year. Casey (Subject 3) is a U.S. citizen who lives on campus in shared dormitory. Lee (Subject 4) is a U.S. resident of mixed Vietnamese and French descent who lives on campus and has been residing in the U.S. for almost 10 years. Raj (Subject 5) lives on campus in a shared dormitory and has been living in the U.S. for almost a year.

Quartz (Subject 6) lives on campus in a shared dormitory and has been residing in the U.S. for almost a year. Ling (Subject 7) lives on campus in a shared dormitory and has been living in the U.S. for almost a year. Sam (Subject 8) lives on campus in shared dormitory and has been residing in the U.S. for almost two years. Jem (Subject 9) lives on campus in a shared dormitory and has been living in the U.S. for a little less than two years. Ringo (Subject 10) lives on campus in a shared dormitory and has been residing in the U.S. for almost six months.

Ming (Subject 11) lives in a shared off-campus apartment and has been living residing in the U.S. for a little over two years. Chao (Subject 12) lives on campus in shared dormitory and has been residing in the U.S. for almost two years. Zander (Subject 13) lives on campus, in shared dormitory, and has been residing in the U.S. for a year and a half. Georgia (Subject 14) lives on campus in a shared dormitory, and has been residing in the U.S. for over a year. Andy lives on campus in shared dormitory and has been living in the U.S. for a little over two years.

Minerva (Subject 16) lives on campus in a shared dormitory and has been residing in the U.S. for six months. Ana (Subject 17) lives on campus in a shared dormitory and has been living in the U.S. for a year and a half. Yan (Subject 18): was born in South Korea but is a U.S. citizen; he lives off campus by himself. Pete (Subject 19) lives on campus in a shared dormitory and has been residing in the U.S. for almost two years. Sean (Subject 20) is a U.S. citizen; he lives on campus in a shared dormitory.

Janie (Subject 21) lives off campus in a shared dormitory and has been residing in the U.S. six months. Tom (Subject 22) lives off campus in a shared dormitory and has been living in the U.S. for little over a year. Zee (Subject 23) lives on campus in a shared dormitory and has been residing in the U.S. for a little over a year. Austin (Subject 24) is a U.S. citizen; he lives on campus in a shared dormitory. Amy (Subject 25): is a U.S. citizen; she lives on campus in shared dormitory. Table 1 below lists the age, sex, ethnicity, and academic career of the interview subjects.

Table 1: Ethnicity, Age, Sex, and Academic Career of Interview Samples

| Student | Age | Sex | Nationality | Academic Career |

| Subject 1 | 19 | F | African-American | Freshmen |

| Subject 2 | 20 | M | Chinese | Sophomore |

| Subject 3 | 20 | M | White-American | Sophomore |

| Subject 4 | 19 | M | Other | Sophomore |

| Subject 5 | 18 | M | Indian | Freshmen |

| Subject 6 | 18 | F | Burmese | Freshmen |

| Subject 7 | 18 | M | Chinese | Freshmen |

| Subject 8 | 30 | M | Chinese | Graduate |

| Subject 9 | 18 | F | Chinese | Freshmen |

| Subject 10 | 19 | M | Chinese | Freshmen |

| Subject 11 | 30 | F | Chinese | Graduate |

| Subject 12 | 27 | M | Chinese | Graduate |

| Subject 13 | 24 | M | Indian | Graduate |

| Subject 14 | 18 | F | Vietnamese | Sophomore |

| Subject 15 | 19 | F | Vietnamese | Sophomore |

| Subject 16 | 29 | F | Bengali | Graduate |

| Subject 17 | 19 | F | Kazak | Sophomore |

| Subject 18 | 25 | M | Vietnamese-American | Sophomore |

| Subject 19 | 18 | M | Chinese | Freshmen |

| Subject 20 | 20 | M | White-American | Junior |

| Subject 21 | 22 | F | Chinese | Graduate |

| Subject 22 | 25 | M | Chinese | Graduate |

| Subject 23 | 23 | M | Chinese | Graduate |

| Subject 24 | 18 | M | White-American | Freshmen |

| Subject 25 | 18 | F | African-American | Freshmen |

Essential to interviews are the directive questions and the “photo-voice” component which allowed students to identify different types of foods in their everyday meal composition from a series of laminated photographs which contain images of both traditional and non-traditional food items (Amos and Lordly 2014). I recorded data from informal and semi-structured interviews using handwritten “jot notes” in the margins of notebook paper (DeWalt and DeWalt 2011:160).

The first section of the interview included questions about students’ demographic information; age, ethnicity and gender. The next section elicited information on their residency status, academic career, and duration of their time in the U.S. The third, and arguably most crucial aspect of the interview entails questions about individual nutrition and past/current meal compositions. Information collected on this topic better ascertain changes in “dietary habitus” and eating behaviors (Sato et al. 2016:174).

The meal compositions of the sample population are determined using 23 laminated photographs that depict different food items. Table 2 below lists the various food items and the number of pictures associated with each respective category.

Table 2: Types of Food Varieties and Number of Illustrative References

| Illustrations of Food Varieties | Number of Pictures |

| Asian Vegetable Types | 1 |

| Domestic Vegetable Types | 3 |

| Domestic and Exotic Fruit Types | 4 |

| Seeds and Nuts | 1 |

| Carbohydrates | 4 |

| Proteins | 1 |

| Cream and Broth Soups | 1 |

| Traditional Vietnamese Pho | 1 |

| Dairy | 1 |

| Sweeteners | 1 |

| Fats, Oils and Butter | 1 |

| Convenience Foods | 1 |

| Traditional Chinese Dishes | 1 |

| Hot and Cold beverages | 1 |

| Dessert Types | 1 |

I directed students to use these photos to construct their current diet. Afterwards, they were asked what their “everyday local diet” was while living at home. They were given the option of using a marker to circle which items they currently eat and those consumed while still living at home. Additionally, the photo-voice interviews were utilized to elucidate the general attitudes and perceptions concerning on campus dining and food choices. The next set of questions elicited information regarding meal frequency, preference, and portion sizes. The middle interview section tasked students with the identification of traditional and non-traditional food items. This portion also contained questions regarding frequency of traditional items consumed in past and current contexts. Finally, the last interview segment included questions regarding self-reported changes in student health, meal times, types of cutlery used while dining on campus, and students’ meal plan status. Field notes and meta-notes were utilized to record, assess, and organize interview responses in addition to the questionnaire survey (DeWalt and DeWalt 2011:160-170).

Semi-structured interviews took place in the library in a private study room. They were recorded digitally with a laptop computer. Informal unrecorded interviews took place in public spaces like the Breezeway, the John C. Hitt library, Starbuck’s, and the Student Union. Direction and aid on conducting and analyzing interviews/surveys by DeWalt and DeWalt (2011) and Fetterman (2010) was integrated into the research design. Interviews lasted between 15 and 45 minutes with some exceeding the allotted time due to extenuating circumstances. To analyze the informal semi-structured interviews, I directly transcribed the audio files to a digital format. The data from informal, unrecorded interviews were transferred from notebooks into a digital format.

To protect confidentiality of the participants, data were stored on password protected computer files to which only the principal investigator had access. With the aid of technology, I directly transcribed the recorded interviews from Windows Media Player to Microsoft Word. It took approximately three hours each to transcribe the five recorded interviews, and several hours to organize all 20 of the informal interviews with photo-voice components. Interview data were then coded for repeated words and phrases. Key events were also highlighted with the aid of different color coded notecards until key categories were identified. The data were coded using the Microsoft Word comment section in addition to color coded notecards. The use of all ethnographic techniques proved useful for data cross-referencing and triangulation (DeWalt and DeWalt 2011:128).

Thirty questionnaire surveys were successfully distributed to not only determine participants’ age and ethnicity, but also their individual food choices, portion sizes, and meal frequencies. Both paper surveys and online surveys were available to students. This instruments included a disclaimer which informed respondents that their participation was completely voluntary and to be kept anonymous. The fast food survey is based on a 2009 fast food survey conducted by Ty Matejowsky (2009) which examines the eating behaviors and preferences of Filipino college students and their consumption of fast food.

My survey is divided into five segments. The first portion asks for demographic information such as participants’ ethnicity, age, and gender. The next section contains questions that inquire about students’ academic career, residency status, and their time spent in the U.S. Following this, the survey contains questions about meal frequency, perceptions about on campus dining, and the consumption patterns of college students. After this, a section gives the respondents the opportunity to discuss their current diet, meal compositions when living back home, and past/current portion sizes. The last section of the survey mainly pertains to international students and their perceptions of traditional versus non-traditional food items. In addition, this section contains questions regarding the frequency in which national cuisines are consumed by international students in the U.S.

The surveys were distributed to UCF students entering/exiting the two campus dining halls or other dining locations. The online surveys were made available to students enrolled in four Department of Anthropology undergraduate courses, and distributed over a six-month period, from October 2016 to March 2017. The sample included anthropology and non-anthropology majors. Students who took online surveys could submit them anonymously through UCF Webcourses. All physical copies were manually entered in an online survey database. The final exclusion criteria for questionnaire surveys call for responses from students between ages 18 and 30. In all, the print survey produces a sample size of n=30. The response rate for the online surveys was zero, and no online surveys are utilized in the study. The questionnaires provide crucial demographic and dietary information of international and domestic UCF students.

The following chapter discusses quantitative measures utilized in the research endeavor. The results are analyzed through statistical analyses to test my hypothesis that ethnicity and a formerly structured “dietary habitus” will influence current individual nutrition evidenced through food choice (Sato et al. 2016:174). The data demonstrate past and current health choices. The hypothesis is supported by the findings from the distributed questionnaire surveys. For my survey data, I originally anticipated compiling a larger sample of male and female Asian international students. Although my sample size falls short of a preferred n=25 for each sample population, the domestic student sample size met expectations. For questionnaires, the total domestic sample consists of n=25 and the international sample is n=5. For my interview data, my goal of interviewing 25 students was accomplished. For interviews, the sample totals were n=7 for domestic students and n=18 for international students.

The international sample size for questionnaire survey, however, only reaches a quarter of what I originally intended. While the survey was offered to a total of over 500 students in various anthropology undergraduate courses, the substantial refusal rate of over 90 percent is not that odd for a study of this type. Though not ideal, the working sample size of n=55 (25 from interview survey and 30 from questionnaire survey) is acceptable for the statistical analyses. In conjunction with the questionnaires’ low response rate, some of the surveys have missing values for specific food choices. Since some students may have unintentionally left out or they could not recall certain aspects regarding their past and present meal compositions, I omit data regarding the carbohydrate and dairy consumption of domestic and international students from quantitative analysis. Notwithstanding such gaps, the recorded/unrecorded semi-structured interviews provide detailed, and completed data for analyses.

The questionnaire survey is divided by demographic information. The domestic sample size for females is n=16 and for males it is n=14. Table 3 below illustrate the age, sex, ethnicity, and academic careers of domestic and international samples.

Table 3: Age, Sex, Ethnicity, and Academic Career of Survey Subjects

| Student | Age | Sex | Ethnicity | Academic Career |

| 1 | 18 | F | White American | Freshmen |

| 2 | 18 | F | Hispanic/Latino | Freshmen |

| 3 | 18 | F | White American | Freshmen |

| 4 | 18 | F | Black American | Freshmen |

| 5 | 18 | F | White American | Freshmen |

| 6 | 19 | F | Black American | Freshmen |

| 7 | 19 | F | White American | Sophomore |

| 8 | 19 | F | White American | Sophomore |

| 9 | 19 | F | Other | Sophomore |

| 10 | 19 | F | White American | Sophomore |

| 11 | 19 | F | White American | Sophomore |

| 12 | 20 | F | White American | Junior |

| 13 | 21 | F | White American | Junior |

| 14 | 21 | F | White American | Freshmen |

| 15 | 18 | M | White American | Freshmen |

| 16 | 18 | M | Hispanic/Latino | Freshmen |

| 17 | 18 | M | White American | Freshmen |

| 18 | 19 | M | Asian American | Freshmen |

| 19 | 19 | M | White American | Sophomore |

| 20 | 19 | M | White American | Sophomore |

| 21 | 20 | M | White American | Sophomore |

| 22 | 20 | M | Black American | Sophomore |

| 23 | 20 | M | Hispanic/Latino | Junior |

| 24 | 21 | M | White American | Junior |

| 25 | 21 | M | Black American | Junior |

| 26 | 18 | F | Chinese | Freshmen |

| 27 | 18 | F | Chinese | Freshmen |

| 28 | 19 | F | Chinese | Sophomore |

| 29 | 18 | M | Chinese | Freshmen |

| 30 | 18 | M | Chinese | Freshmen |

Regarding health and nutrition, I created categories for individual food and beverage items. To gauge differentiations in health and nutrition, while I categorize fruits and vegetables as healthy food choices, I assign the label “unhealthy” to foods containing high amounts sugar, sodium and fat such as ice cream, cake, and chips. For other items like protein, starch, dairy, and carbohydrates, the categories are more nuanced as they can be either nutritious versions or calorically dense. Chicken, fish, seafood, lamb, turkey, and tofu are considered healthy sources of protein whereas beef and pork are considered less healthy. Healthy carbohydrates include items such as rice, rice noodle, vermicelli noodle, flat bread, whole wheat bread, sweet potatoes, baked potatoes, seeds, nuts, corn tortillas and wraps. Unhealthy carbohydrates include things like pasta, white bread, croissants, bagels, donuts, egg noodles, and any bread product that is bleached or processed. Healthy dairy products include yogurt, kefir, and milk. Unhealthy dairy products encompass things like butter, ice cream, cream, cheese, and sour cream. To clarify, I consider cheese as unhealthy in many instances because students regularly consume it in large quantities, and the American cheeses/cheese sauces primarily offered by on campus dining locations are processed or high in fat. Moreover, unhealthy convenience foods entail foods such as pizza, hamburgers, hotdogs, pizza, chicken nuggets, fried chicken, chicken patties, quesadillas, sandwiches, kebabs, fish sticks, chicken wings, and tacos. As for beverages, I ascribe the term healthy to water, fresh fruit juices, coffee, and tea while unhealthy beverages include hot chocolate, soft drinks, and some caffeinated beverages.

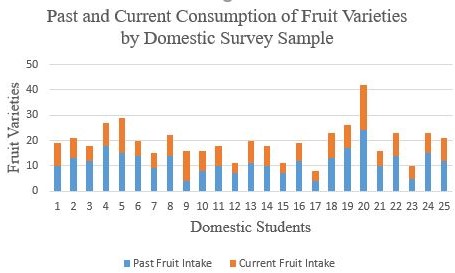

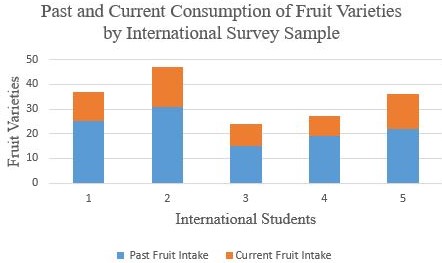

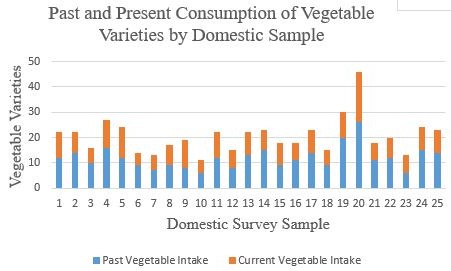

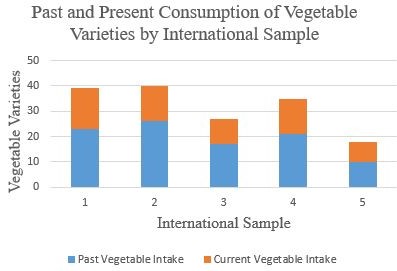

The results from the survey questionnaire demonstrate that while domestic students eat a greater variety of convenience foods they consume less varieties of fruits and vegetables. Figures 1 through 4 demonstrate differences between both sample populations. Figures 1 and 2 pertain to fruit intake, and Figures 3 and 4 pertain to vegetable consumption.

Figure 1: Past and Current Consumption of Fruit Varieties by Domestic Survey Sample

Figure 2: Past and Current Consumption of Fruit Varieties by International Survey Sample

Figure 3: Past and Present Consumption of Vegetable Varieties by Domestic Sample

Figure 4: Past and Present Consumption of Vegetable Varieties by International Sample

Findings show that on average that domestic students ate 11.52 types of fruit prior to coming to UCF, and currently eat an average of 8.16 varieties while attending university. This represents a 29 percent decrease in fruit types. As for vegetable variety, domestic students ate 11.92 vegetable types while living at home and currently eat 8.68 types. This is a 27 percent decrease in vegetable types. International students average 22.4 types of fruit before, but since relocating to the U.S., they eat an average of 11.8 varieties which stands as a 47 percent decrease in fruit types. On average, students within the international sample ate 19.4 types of vegetables in their home country. Today, they currently eat an average of 12.4 types in the U.S; a 36 percent decrease. While international students experience substantial decreases in their consumption of different fruit and vegetable varieties, they currently eat 3.64 more fruit types and 3.72 vegetable types than their domestic counterparts. When comparing past fruit consumption, the international sample on average ate an average of 10.88 more types of fruits before, and 8.2 types of vegetables.

Besides fruits and vegetables, questions pertaining to convenience foods also yield valuable insights. To further operationalize, convenience foods generally lack fresh, home-cooked or slow-cook elements characteristic of many traditional foods. Similar to Alakaam et al. (2015:109) I define unhealthy convenience foods as rapidly-prepared cuisines that are processed and high in fat, sodium, and/or sugar. Specifically, I regard chips, pizza, hamburgers, chicken nuggets, chicken patties, nachos, doughnuts, tacos, Lunchables, and cookies as unhealthy. Some national cuisines such as sushi or stir-fry also are included in the categorization of convenience foods as they can be rapidly prepared in a short amount of time. I consider sushi, edamame, salsa, falafel, pretzels, flatbreads, and pita and hummus as healthy forms of convenience cuisines.

Findings demonstrate that domestic students ate 6.12 types of convenience food in their home environment, and currently eat an average of 7.16. This is an increase of approximately 17 percent. Moreover, international students ate 4.6 types while living in their country of origin, and eat six types of convenience foods in the United States. This is an approximate 23 percent increase in convenience foods. The data show that domestic and international students saw similar increases in their consumption of convenience food varieties. International students appear to eat 1 less type of convenience foods in the university foodscape. However, comparisons between the past consumption of convenience foods of both sample populations, international students ate on average one 1.52 less types of convenience foods in their home country. The data supports my hypothesis that international students are less likely to eat convenience foods and more likely to eat healthier alternatives.

The questionnaire survey also provides analysis regarding portion sizes. Responses indicate increases/decreases in serving sizes in both sample populations. For the domestic sample, eight students admit that they eat large portions, ten state that they consume medium portions, and seven report eating small portions. When asked about how their portion sizes have changed over time, six said they eat larger portions now, three said that they eat a little more, nine said they ate the same, four say they eat a little less, and three say they eat less. For the international sample, two students admit to eating small potions, two currently eat medium portions, and one now eats large portions. Moreover, the international students’ portion sizes did not dramatically fluctuate, seeing as two eat the same portions sizes, one eats a little more, one eats a little less, and another student reports eating less.

Given my thesis’s research objectives, it is important to consider the dining preferences of students who eat on campus. The frequency in which students dine on campus is as follows, ten students eat on campus once a day, five students eat on campus multiple times a day, seven students dine on campus three to five times per week, and two students eat on campus once or twice a week. The international sample reports that three of the students eat on campus once a day while the other two eat on campus multiple times per week. All the respondents report that on campus dining is convenient. Eighty percent of the domestic sample considers on campus dining as nutritious whereas 20 percent consider food on campus to be neither good nor bad. Additionally, the majority of both student sample populations consider food on campus as a formal snack, and only three students reason that it is both a formal meal and a snack. Moreover, surveys show an overwhelming preference for the dining halls and restaurants featured in the Student Union. Findings are consistent with data collected from ethnographic interviews.

All five international students report eating traditional foods at least twice a week. No students report eating traditional diets while living in the U.S. Four out of five students admit that they ate traditional diets growing up in China; however, one of the female participants reports that she did not eat traditional foods consistently when she lived in Hong Kong. The findings are consistent with interview results discussed in the next subsection.

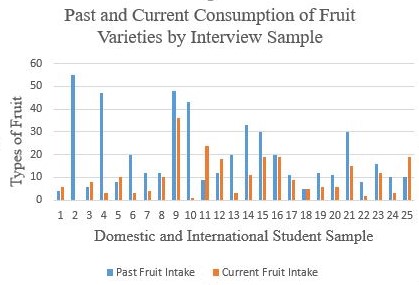

The interview sample consists of n=25. The seven domestic students include: subjects 1,3,4, 18, 20, 24, and 25. The 18 international students include: subjects 2, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 19, 21, 22, and 23. Names, demographic information, and corresponding subject numbers are listed in Chapter Three. Figures 5 and 6 below demonstrate marked differences in fruit and vegetable consumption over time.

Figure 5: Past and Present Consumption of Vegetable Varieties by Interview Sample

Figure 6: Past and Present Consumption of Fruit Varieties by Interview Sample

For fruit and vegetable consumption, I took the averages from the international and domestic interview samples for analysis. In terms of their past fruit intake, international students average 22.17 types of fruit, and 26.1 types of vegetables whereas the domestic sample average 13.2 fruit types, and 10.71 vegetable varieties. The current average amount of fruit varieties consumed from the international student sample is 11.2 and the average for the domestic sample is 7.14. The current mean amount of vegetable types consumed from the international student sample is 13.2 and the mean for the domestic sample is 12. International students experience approximately a 49.5 percent decrease in their average fruit consumption, and a 49.4 percent decrease in their vegetable varieties. Alternatively, the domestic students experience a 45.6 percent reduction in their average consumption of fruit varieties, and a 16.9 percent decrease in their average consumption of vegetable types.

Analyses of the data show that both student samples increased their consumption of healthy and unhealthy dairy products after moving to UCF. Most interviewees eat cheese in large quantities, sometimes double or triple the recommended serving sizes which relegates it to the unhealthy category. Swiss and provolone cheeses are considered healthy, but they are not always readily available on campus. On average, international students eat 1.72 healthy dairy types and 1.52 unhealthy varieties in their diet. Comparisons with past meal composition indicate a 13.3 percent average increase in healthy types and a 110 percent increase in unhealthy dairy varieties. Domestic students average 1.43 healthy dairy products and 1.86 unhealthy types. Comparisons exhibit a 16.2 percent increase in healthy dairy types and an eight percent increase of unhealthy varieties from when subjects lived at home. The variables attributing to the substantial increase in dairy consumption of international students is discussed in more detail in Chapter Five.

As for carbohydrates, the mean amount of current unhealthy types consumed by international students is 2.61, and they average 1.78 for healthy carbohydrates. Results show that international students experience an 11 percent decrease in healthy carbs, and a 51.7 percent increase in unhealthy varieties. The domestic sample currently averages 3.86 types of unhealthy carbohydrates and 1.56 types of unhealthy carbohydrates. They experience a 22 percent decrease in healthy varieties and a 35 percent increase in unhealthy types. International students are better suited to maintain their consumption of unhealthy carbs. However, the domestic students saw a considerable increase in the amount of unhealthy varieties. On average, most international students eat less types of unhealthy carbohydrates.

The results from interview exhibit surprising results. On average, the international sample consumes 2.37 types of healthy protein and 1.68 unhealthy types. In the past, students ate 2.89 healthy types and 1.68 healthy types. The data exhibits an 18 percent decrease in healthy forms of protein, but no change in the amount of unhealthy protein consumption. The domestic sample eats an average of 1.71 types of both healthy and unhealthy protein; in the past, they consumed two healthy types and 1.86 unhealthy varieties. The survey findings show a 14.5 percent decrease in healthy protein types, and an eight percent decrease in unhealthy protein varieties.

The results from the survey questionnaires are consistent with findings from interviews and participant observation. Domestic students typically eat a greater variety of unhealthy convenience foods while international students tend to restrict their consumption of processed and high-fat foodstuffs. Domestic students average 4.71 types of convenience foods. This is a 65.2 percent increase from when they were in high school, while the international students average approximately 2.89. This is a 68 percent increase from the amount they ate while living in their home country. It appears that both sample populations experience dramatic increases in their consumption of convenience foods which is contrary to my expectations. Nevertheless, international students on average eat about 1.82 less types of convenience foods in the U.S., and ate 1.13 less types in their country of origin.

Overall, the findings suggest that living away from home for the first time in on campus foodscape in conjunction with readily accessible fast food enterprises can lead to an inflation of convenience cuisines in the diets of both international and domestic students. They also indicate that both international and domestic students experience reductions in both their fruit and vegetable intake. However, data from interviews and questionnaire survey also demonstrate that international students on average eat more varieties of fruits and vegetables in comparison to the domestic sample. The next chapter discusses qualitative data analysis.

The qualitative research discussed in this chapter was conducted with special emphasis on how cultural differences inform matters of food preference and meal choice. First, I discuss the categorizations I created for the various on campus eateries. Next, I discuss the three main codes which are as follows: (1) eating behaviors and meal composition before and after attending university; (2) factors that influence changes in eating habits post-migration, evidenced through accessibility and the on campus food environment; and (3) counteraction to dietary changes through food preferences, support networks, and consumption of national cuisines. The section on food preferences is divided into four sub-categories: fruit and vegetable intake, protein intake, carbohydrate and dairy intake, and convenience foods.

These categories emerged as viable over the course of interviews, demonstrating two distinctly different conceptions of health and nutrition which are based on preexisting cultural attitudes and beliefs about food. I illustrate the differences and similarities of international and domestic students’ dietary choices. In addition to dietary preferences, I also describe changes to students’ portion sizes over time. Also significant are the meal duration, and time spent consuming on food specific items. Finally, I discuss the consumption of traditional foods and national cuisines.

To better analyze student diets, I created etic categories for the various eateries on campus dining facilities in terms of food items available to students These categories include “unhealthy,” and “healthy” dining facilities. I categorized 63 South, Knightro’s, Pita Stop, Qdoba, Knightstop & Sushi, Corner Cafe as healthy dining choices since they offered fruits and vegetables or foods that were alternatives to convenience foods. Domino’s, Chik-fil-A, Café Bustelo, Huey Magoo’s, Nathan’s Famous, Jimmy John’s, Java City, Asian Chao, Smoothie King, Einstein’s Bagels, Kyoto Sushi & Grill, Mrs. Field’s Bakery, Topper’s Creamery, Dunkin Donuts, and Burger U as unhealthy dining institutions because most of their menu items are mainly convenience foods, and fast food items that are either high in fat and sugar or are of little nutritional value. In addition, to address differentiation in vegetable and fruit varieties I categorized anyone who ate less than ten fruit types as having “low variety,” between ten and 19 as “moderate variety,” and anyone who eats more than 20 types is assigned “high variety.” The ascribed categories were useful in determining what students were eating while dining in the Student Union and elsewhere on campus.

Additionally, I assign arbitrary categories for fruit, vegetable, dairy, carbohydrates, and convenience food consumption. To measure changes in fruit and vegetable diversity, I use the following categories: nine or less types would fall into the low variety category, between ten and 19 types entails moderate levels of variety, and if the respondent ate 20 or more types they would fall into the high variety categorization. I tracked frequency changes for dairy by labeling products healthy or unhealthy. Unhealthy types include cheese (if students consume it large quantities or American varieties), sour cream, butter ( if students consume in large quantities), and ice cream, while healthy types consisted of yogurt, milk, swiss and provolone cheeses, and kefir. Consuming three or more types of unhealthy dairy products indicates unhealthy eating habits; conversely, eating three or more types of healthy dairy is considered nutritious. Accordingly, the same categorizations of health are applied to carbohydrates (i.e. pasta, bread, and noodles), and types of protein (chicken, beef, pork, lamb, fish, and miscellaneous seafood items). Changes are indicated by increase or decrease in the consumption of each.

My study also assesses beverage consumption. Beverages such as soda, sweet tea, hot chocolate, milkshakes, ice cream smoothies, energy drinks and other miscellaneous soft drinks are considered unhealthy. Conversely, healthy beverages include: water, unsweetened tea/coffee, and fruit juices. Most Asian international students admit that they drank soda when they were younger but have since abandoned that habit, considering it to be too unhealthy or full of “empty calories.”

To gauge the duration of meal times. I record how long students spent eating. “Structured dietary behaviors” are usually indicative of healthy dietary habits (Alakaam et al. 2015:109). Similar to Alakaam et Al. (2015) I attribute structured eating behaviors to students who eat three or more meals a day, at similar times or periods, and for periods longer than ten minutes. Conversely, I ascribe “unstructured eating behaviors” to student who skipped meals, frequently snacked, ate at erratic times of the day, and finished their meals in less than ten minutes.

My stated hypothesis is tested through various methodologies. These include surveys, unrecorded/recorded semi-structured interviews. The main aim of these ethnographic techniques is to generate a data base that offers a comparative analysis of students’ past meal compositions and their current food choices. Moreover, the data collected from domestic college students are compared to the responses of my defined sample group.

Informal and semi-structured interviews along with field notes and photographs are coded to identify any emergent themes and categories. Using grounded theory, I code for diverse data sets (Ralph et al. 2015). The types of coding techniques used in data analysis include descriptive coding, process coding, in vivo coding, pattern coding, and simultaneous coding (DeWalt and DeWalt 2011:183-184). This analysis includes an in-depth examination of meal composition in an urban campus environment. The data are relevant as they elucidate how and why international students alter or hybridize their meal composition while attending a major U.S. university.

Findings derived from both participant observation and interviews suggest that international students choose to eat together in a context of relaxation, studying, and recreating feelings of home. I frequently observed international students dining together in groups. Eating with other international students, particularly those from the same region or country, helps reinforce social bonds and preserve cultural identity while concurrently satisfying rudimentary nutritional requirements. Anthropologists Amos and Lordly (2014) also discuss similar commensal behaviors in their paper on international students.