Chapter 1: Introduction and Scope

There are two types of abortion: medical and surgical. Medical abortions involve the patient taking a medication or combination of medications to induce a miscarriage. Surgical abortions involve dilating the cervix and using a vacuum and forceps to remove a fetus (Safe Abortion, 2012). Rewrite: The definition of abortion is shared by numerous health organizations (e.g., National Ctr for Health Statistis, CDC, WHO) and includes ending pregnancy up to 20 weeks gestation or extraction of an undeveloped fetus at 500 grams (Schorge et al., 2008). “The National Center for Health Statistics, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and the World Health Organization (WHO) define abortion as pregnancy termination prior to 20 weeks gestation or a fetus born weighing less than 500 g” (Schorge et al, 2008).

Access to abortion is an issue across the nation, however, abortions will continue to occur regardless of legality. The difference is that illegal abortions have a higher chance of being botched and unsafe and are likely to create more medical costs in the long run. The state of Indiana has mandated multiple steps for patients to take before receiving an abortion, as will be discussed further. Abortion access has been a long fought battle and will likely continue to be due to various restrictions.

There are several components mentioned in this paper that factor into access to abortion including policy, cost, availability of locations, and social stigma. Two recommendations in response to abortion restrictions are either policy changes and increased funding to make abortions more affordable or increased comprehensive sex education and access to contraceptives to prevent pregnancy.

Chapter 2: Historical, sociocultural, and institutional context

Women globally have used abortion as a means to control their reproductive health in all points in history. Prior to the 1880s, abortion was widely practiced in America. Around this time, however, abortion was banned in most states unless a woman’s life was threatened (Obos Abortion Contributors, 2016). Anti-abortion laws emerged to counter the suffrage movement and access to birth control. This effort was mainly directed at controlling women’s reproduction and confining them to traditional childbearing roles (Obos Abortion Contributors, 2016). Furthermore, the United States government was deeply concerned about “race suicide” and wanted women from Northern European backgrounds to continue giving birth (National Abortion Federation, 2017).

Another force behind the drive to make abortion illegal was the attempt by doctors to establish exclusive rights to practice medicine. They wished to keep midwives, apothecaries, and homeopaths from competing with them for patients and patient fees. Instead of admitting these motivations, The American Medical Association declared that abortion was immoral and dangerous. By 1910, all but one state had criminalized abortion. In this way, legal abortion became a “physician’s only” practice (National Abortion Federation, 2017).

The new laws surrounding abortion did not reduce the number of women who sought them (National Abortion Federation, 2017). Poor women and women of color suffered disproportionately, as their ability to receive safe abortions was dependent on their economic situation, race, and geographic location. While women with financial stability could potentially afford to leave the country to receive an abortion, poor and minority women often attempted dangerous self-abortions with coat hangers and knitting needles (Obos Abortion Contributors, 2016). Though it is unknown how many women died due to unsafe abortion practices, but thousands of women a year were treated for health complications or left infertile and with chronic pain (National Abortion Federation, 2017).

Before Roe vs. Wade, some physicians and medical practitioners risked imprisonment and loss of their medical licenses to provide safe abortions to women. In the 1960s, The Clergy Consultation Service on Abortion set up referral systems to aid women in locating safer illegal abortions. Second wave feminist groups also formed their own groups to provide abortion referrals to women. Furthermore, in 1969, the Chicago Women’s Liberation Union created an underground feminist abortion service. Over four years, this group provided around 11,000 safe and inexpensive abortions to women (Obos Abortion Contributors, 2016).

Inspired by the civil rights movement in the 1960s, women organized a women’s liberation movement where reproductive rights were a top priority. From 1967-1973, fourteen states reformed their abortion laws and four states repealed them all together. Some of the legal changes included allowing women to access abortions in cases of rape and incest. In 1970, New York became the first state to legalize abortion through the 24th week of pregnancy, and Alaska and Washington followed suit (Obos Abortion Contributors, 2016).

On January 22, 1973, the United States Supreme Court overturned all existing criminal abortion laws in the Roe v. Wade decision, dramatically decreasing pregnancy-related injury and death (National Abortion Federation, 2017). A woman’s right to end her pregnancy in the first trimester was protected under the Fourteenth Amendment’s concept of personal liberty. Still yet, the court allowed states to place their own restrictions on second and third trimester abortions (Obos Abortion Contributors, 2016).

From 1973-1993, the United States Supreme Court rejected multiple state efforts to limit women’s access to abortion but made two rulings that restricted young and poor women’s access to abortion. The ruling in Bellotti v. Baird in 1979 allowed states to insist upon parental consent for a minor to receive an abortion. The Hyde Amendment, passed in 1976, banned the use of federal funding for abortion care and services, except in limited circumstances (Guttmacher Institute, 2017). After this, most states banned the use of Medicaid to cover abortions. This decision effectively made it extremely challenging for low-income women, who were generally women of color, to access abortions. Though the Hyde Amendment was challenged, Harris v. McRae upheld the amendment stating women’s constitutional rights were not violated by banning federal funding for abortions (Obos Abortion Contributors, 2016).

The next major Supreme Court decision regarding abortion occurred in 1992 in Planned Parenthood v. Casey. This ruling upheld an exceptionally restrictive Pennsylvania law that was comprised of mandatory waiting periods, parental consent, and bias information (Obos Abortion Contributors, 2016). In addition, the court abandoned the principles of Roe v. Wade and made it legal to limit access to abortion at any stage of pregnancy, as long as the law did not place “undue burden” on access to abortion (National Abortion Federation, 2017).

Following the Planned Parenthood v. Casey ruling, state and local legislatures began passing more restrictive abortion laws which have generally been protected by the Supreme Court. According to the Guttmacher Institute, 1074 abortion restrictions have been enacted since Roe v. Wade, with more than 25% of them passed between 2010 and 2015 (2017). These restrictions include bans on late term abortion, limitations on medication abortion, enforcement of waiting periods, and targeted regulation of abortion providers (TRAP) (Obos Abortion Contributors, 2016).

Anti-abortion advocates have used the argument of “personhood” to attempt passing laws that define zygotes, embryos, and fetuses and “persons.” The goal of these personhood laws is to criminalize abortion (Obos Abortion Contributors, 2016). In addition, arguing for morality and addressing abortion from a religious context has served as a strong basis to support restrictive abortion laws (Guttmacher Institute, 2017)

In 2016, seventeen states funded abortion services on the same terms as other pregnancy services, meaning the states used their own funding to cover abortions. Thirty-two states only provided abortions in the context outlined by the Hyde amendment (Guttmacher Institute, 2017). California is the only state that requires insurance companies cover abortions in their employer plans, leaving around 1.2 million women without access to affordable coverage for abortion care (Obos Abortion Contributors, 2016). In forty-five states, health care providers can refuse to participate in an abortion, and 42 states allow institutions to refuse to perform abortions due to religious reasons. In 16 states, it is required that women receive “counseling” before an abortion to give them information on one of the following: the claim a link exists between abortion and breast cancer, the ability of the fetus to experience pain, and the long-lasting mental health consequences for women after abortions. Furthermore, twenty-seven states require a woman to wait a certain period of time before receiving an abortion, and thirty-seven states require parental involvement for minors-some states even require both parents to consent (Guttmacher Institute, 2017).

Chapter 3: Statistics and tables/graphs/charts

National Perspective

As of 2014, around 926,200 abortions were performed in the United States, down by 12% since 2011. The abortion rate in 2014 was 14.6 abortions per 1,000 women aged 15-44 (see Figure 1), making this the lowest rate ever observed in the United States (Guttmacher Institute, 2017). Planned Parenthood representatives believe these decreased rates are a result of better access to contraceptives, improvements in the rate of unintended pregnancies, and a historically low teen pregnancy rate (2017).

National Abortion Trends, Figure 1

Over half of US abortion patients in 2014 were women in their 20s, while 12% of abortions were received by adolescents. White women accounted for 39% of abortion procedures with African American women at 28% and Hispanic women at 25%. Because whites generally experience fewer barriers to health services and greater financial stability compared to women of color, it is unsurprising that white women have the highest abortion rates by race/ethnicity. Almost all abortion patients in 2014 identified as heterosexual and a little under half were neither married or cohabitating with a partner. The most common reasons for receiving an abortion were one of the following: responsibility to other individuals, inability to afford raising a child, and the belief a child would interfere with work, school, or caring for dependents (Guttmacher Institute, 2017).

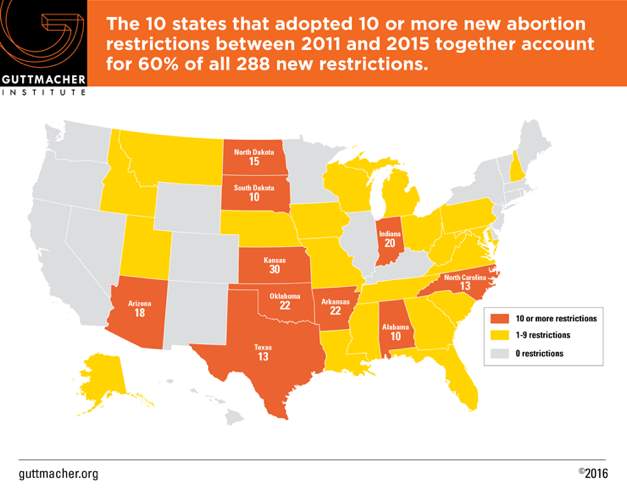

Ten states adopted at least ten restrictive abortion laws between 2011 and 2015 (see Map 1), with Indiana being one of these states (Guttmacher Institute, 2017). These restrictions fall into four categories: Targeted restrictions on abortion providers (TRAP), limitations on insurance coverage, bans on abortions at 20 weeks postfertilization, and limitations on medicine abortion. To put this into perspective, states enacted 93 restrictive measures in these categories from 2011-2013, compared to 22 measures in the past decade (Guttmacher Institute, 2017).

New Abortion Restrictions, Map 1

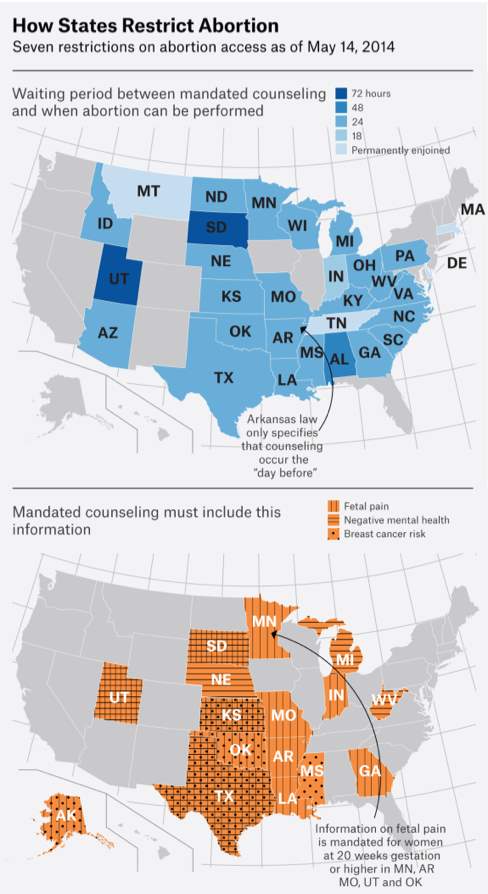

As of 2014, 29 states had laws making it mandatory for women to receive counseling before receiving an abortion (see map 2). These states also had specific waiting periods between counseling and when an abortion could be performed. This varied from 18 hours to 72 hours. Mandated counseling included information on fetal pain, negative mental health, and/or link to breast cancer. The bottom of map 2 shows which states mandated which forms of counseling for those seeking an abortion in 2014 (Guttmacher Institute, 2017).

Abortion Restrictions (Counseling), Map 2

Indiana Abortion Rates

In 2014, an estimated 8,180 abortions were provided in Indiana, making up 0.9% of abortions in the United States (Guttmacher Institute, 2017). The Center for Disease Control and Prevention reported that 5.3% of these abortions were performed on out-of-state-residents that traveled to Indiana for the procedure (2014). There was a 14% decline in the abortion rate in Indiana between 2011 and 2014, from 7.3 to 6.3 abortions per 1,000 women of reproductive age (Guttmacher Institute, 2017). The age range for women receiving abortions in Indiana in 2014 was 13-50 years (see Table 1). The average age of a woman who obtained a termination was 26.4 years with a median age of 25 (Indiana State Department of Health, 2014).

Age Distribution of Women Obtaining Abortions in Indiana, 2014, Table 1

| Age(years) | Count | Percent |

| 10-14 | 21 | 0.26 |

| 15-17 | 269 | 3.31 |

| 18-19 | 638 | 7.86 |

| 20-24 | 2,698 | 33.23 |

| 25-29 | 2,164 | 26.66 |

| 30-34 | 1,311 | 16.15 |

| 35-39 | 767 | 9.45 |

| 40-44 | 234 | 2.88 |

| ≥ 45 | 16 | 0.20 |

| Total | 8,118 | 100.0 |

For each age group in Table 1, more than half of the women were white. Based on cross-tabulation of each age group by race (see Table 2), white women in their twenties received the most abortions in Indiana in 2014 (Indiana State Department of Health, 2014).

Age of women obtaining abortions in Indiana by Race, 2014, Table 2

| Age Group | Race | Total | |||||||

| White | Black | Other | Unknown | ||||||

| Count | % | Count | % | Count | % | Count | % | ||

| Adolescent (≤ 19) | 546 | 58.84 | 251 | 27.05 | 121 | 13.04 | 10 | 1.08 | 928 |

| Twenties (20-29) | 2,834 | 58.29 | 1,436 | 29.54 | 536 | 11.02 | 56 | 1.15 | 4,862 |

| Thirties (30-39) | 1,201 | 57.80 | 591 | 28.44 | 253 | 12.18 | 33 | 1.59 | 2,078 |

| Forties & Over (≥ 40) | 157 | 62.80 | 49 | 19.60 | 40 | 16.00 | 4 | 1.60 | 250 |

| Total | 4,738 | 2,327 | 950 | 103 | 8,118 | ||||

As briefly mentioned above, in the state of Indiana, as of April 1 2017, women seeking abortions are required to receive state-directed counseling that includes information to discourage abortions, and then wait 18 hours before the procedure is administered (see Table 6). Private insurance policies will only cover the abortion in instances of life endangerment, rape, incest, or if the woman’s health is seriously compromised (see Table 5). Additionally, the Affordable Care Act only covers abortions in these same instances. Public funding is only available for abortions in cases of life endangerment, rape and incest, and the prevention of long-lasting damage to the women’s physical health (Guttmacher Institute, 2017).

The parent of a minor must provide consent before the abortion is performed (see Table 6), and women must undergo an ultrasound, with the option of viewing the image, before obtaining an abortion. An abortion may be performed at 20 weeks (see Table 5) or more post fertilization only if a woman’s life or health is dangerously compromised (Guttmacher Institute, 2017).

Overview of Indiana Abortion Law, Table 5

| Must be performed by a licensed physician | Must be performed in a hospital if at: | Second physicians must participate if at: | Prohibited except in cases of life or health endangerment if at: | “Partial-birth” abortion prohibited | Public Funding covers all or most medically necessary abortions | Public funding only covers abortion in cases of rape/incest or the endangerment of life | Private insurance coverage limited |

| X | 20 weeks | 20 weeks | 20 weeks (unless a woman’s health is threatened) | X | X | X |

Guttmacher Institute, 2017

Overview of Indiana Abortion Law, Table 6

| Individual Providers may refuse to participate | Institutional providers may refuse to participate | Mandated counseling on breast cancer link | Mandated counseling on fetal pain | Mandated counseling on negative psychological effects | Waiting period (in hours) after counseling | Parental involvement required for minors |

| X | Private | X | 18 | Consent |

Guttmacher Institute, 2017

Chapter 4: Analysis of County or Regional Differences

There were 12 Indiana facilities that provided abortions in 2014, with 9 of them being clinics (see Table 3). According to the Indiana State Health Department, the most abortions in 2014 were received in Indianapolis. Still yet, 95% of Indiana counties had no clinics that provided abortion services, but 66% of Indiana women lived in these counties (Guttmacher Institute, 2017). This leaves multiple areas in Indiana without an abortion clinic. Therefore, low-income women and individuals without transportation may have significant challenges accessing these services. Considering that individuals in Indiana must undergo counseling and a waiting period before the procedure, this makes it even more difficult for women traveling a distance to receive an abortion. In addition to worrying about abortion costs, women must contemplate additional travel and lodging costs.

Abortions by Indiana Facility, Table 3

| Facility Type | Facility Name | Facility Address | Count | Percent |

| Abortion Clinic | Affiliated Women’s Services, Inc. | 2215 Distributors Dr. Indianapolis | 32 | 0.39 |

| Clinic for Women | 3607 W. 16th St. | 988 | 12.29 | |

| Friendship Family Planning Clinic of Indiana | 3700 Broadway Gary | 158 | 1.95 | |

| Indianapolis Women’s Center | 1201 N. Arlington Ave. Indianapolis | 1,179 | 14.52 | |

| Planned Parenthood of Indiana and Kentucky– Indianapolis | 8590 Georgetown Rd. Indianapolis | 2,973 | 36.62 | |

| Planned Parenthood of Indiana and Kentucky – Bloomington | 421 S. College Ave. Bloomington | 718 | 8.84 | |

| Planned Parenthood of Indiana and Kentucky – Lafayette | 964 Mezzanine Dr. Lafayette | 169 | 2.08 | |

| Planned Parenthood of Indiana and Kentucky – Merrillville | 8645 Connecticut St. Merrillville | 1,070 | 13.18 | |

| Women’s Pavilion | 2010 Ironwood Cir. South Bend | 788 | 9.71 | |

| Acute Care Hospital | Indiana University Health University Hospital | 550 University Blvd. Indianapolis | 4 | 0.05 |

| Sidney & Lois Eskenazi Hospital | 720 Eskenazi Ave. Indianapolis | 28 | 0.34 | |

| Ambulatory Surgical Center | Community Surgery Center North | 8040 Clearvista Pkwy. Indianapolis | 1 | 0.01 |

| Total | 8,118 | 99.98* | ||

Table 4 below shows the number of residents under 20 years of age and over 20 years of age who received an abortion by county. Unsurprisingly, as most abortions in Indiana were received in Indianapolis in 2014, Marion County (the county Indianapolis is located in) also had the largest number of female residents obtaining abortions in 2014 (35.02%). Lake County accounted for 9.32% of residential abortions, while St. Joseph and Allen counties each accounted for just over 4% of residential abortions (Indiana State Department of Health, 2014).

Number of Abortions by County, Table 4

| County of Residence* | Count | Percent of All Residents | |

| Adolescent (< 20) | Adult (≥ 20) | ||

| Allen | 33 | 297 | 4.33 |

| Bartholomew | 4 | 77 | 1.06 |

| Delaware | 24 | 103 | 1.67 |

| Elkhart | 13 | 144 | 2.06 |

| Hamilton | 25 | 268 | 3.84 |

| Hendricks | 24 | 140 | 2.15 |

| Howard | 13 | 81 | 1.23 |

| Johnson | 21 | 160 | 2.38 |

| Lake | 86 | 624 | 9.32 |

| LaPorte | 14 | 120 | 1.76 |

| Madison | 20 | 116 | 1.78 |

| Marion | 250 | 2,419 | 35.02 |

| Monroe | 29 | 219 | 3.25 |

| Porter | 32 | 163 | 2.56 |

| St. Joseph | 47 | 290 | 4.42 |

| Tippecanoe | 33 | 224 | 3.37 |

| Vanderburgh | 9 | 117 | 1.65 |

| Vigo | 15 | 90 | 1.38 |

All-Options Pregnancy Resource Center in Bloomington, Indiana has a fund called the “Hoosier Abortion Fund” set up to help women obtain an abortion. They prioritize funds to be used for women who are 10 weeks pregnant due to Indiana’s restrictive laws. All-Options covers the cost of the procedure and related costs, such as transportation and child care. Bloomington also has a Planned Parenthood clinic that provides abortion services.

Chapter 5: Methodology/Bias

The Terminated Pregnancy Report for Indiana is produced every year to provide an overview of abortions performed in the state through the previous year (Indiana State Department of Health, 2014). Data is directly reported to the Indiana State Department’s Division of Vital Records through an electronic database. All personally identifiable information is stripped from the data to maintain confidentiality. Information provided by the patient and medical reports include age, marital status, education level, race, ethnicity, county of residence, and state of residence. In addition, patients report the number of live births where the child is living, the number of live births where the child is deceased, the number of previous spontaneous terminations, the number of previous induced terminations (excluding the one being reported), dates of past terminations, and the date their last normal menstrual cycle began. The medical information on reports is collected by the physician. This information includes the following: date of termination, viability of fetus, fetus delivered alive, completion of a pathological examination of the fetus, procedure used for termination, complications, result in maternal death, estimated gestational/post fertilization age, and method used to determine gestational age. Other information includes the name of the facility where the abortion was performed, the city or town of the abortion, the county of the abortion, and the physician’s contact information (Indiana State Department of Health, 2014).

The cut-off for the publication of Indiana’s Terminated Pregnancy Report is mid-year, meaning a cut-off date was determined to create the 2014 dataset. As a result, there is a possibility reports were submitted after the cut-off date that were not included in the report. The number of abortions for the year, consequently, may be slightly lower than the true total (Indiana State Department of Health, 2014). In addition, the data does not show the whole picture in respect to abortions and location. For example, more people in Indiana may have received an abortion, but if they did so out of state, the abortion would not be included in the Indiana report.

Chapter 6: Policy Debates

Indiana abortion policies, as well as abortion policies in many other states, have become increasingly more restrictive. Vice President Mike Pence has been a major driver of this trend. Vice President Pence was first elected as an Indiana congressman in 2000 (The White House, 2017) and rose among republican ranks throughout subsequent congressional terms.

Vice President Pence has been particularly steadfast in his goal to defund Planned Parenthood. He first introduced federal legislation to defund Planned Parenthood in 2007 as an amendment to an appropriations bill. (Politico, 2011). The bill failed, but Vice President Pence continued to focus his efforts on this cause, requesting a report from the Government Accountability Office on how much federal funding abortion providers receive, despite the Hyde Amendment prohibiting federal funds from being used for abortion services. (Guttmacher Institute, 2017). Vice President Pence argued that, “if you follow the money, you can actually take the funding supports out of abortion” (Politico, 2011).

Planned Parenthood receives its funding from two main sources – Medicaid and Title X (NPR, 2015). Title X is a federal grant program that provides funds for comprehensive family planning and related preventative health services (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2017) to low income individuals. By removing this source of funding, Planned Parenthood would be rendered functionally incapable of providing their primary services of contraception, STI testing, preventive wellness exams, and many other non-abortion services. In 2011, Vice President Pence sponsored another measure to defund Planned Parenthood in the form of an amendment to the proposed federal budget. The budget passed the House but failed to pass the Senate in a last-minute decision that narrowly avoided a government shutdown. (Washington Post, 2011).

Between 2011 and 2016, the political landscape in America changed dramatically. The conservative Christian right embraced the topic of abortion as a platform, which they had been avoiding prior to the 2012 election in fear of alienating voters. In 2015, an anti-abortion group called the Center for Medical Progress (CMP) released a series of videos in which they claimed that Planned Parenthood officials were selling and profiting off of fetal tissue for research (Guttmacher Institute, 2016). Then-Governor Mike Pence launched an independent investigation into the videos, which found no wrongdoing on the part of Planned Parenthood. The videos were proven false, and those responsible at CMP have been charged with 15 counts of felony crime (Washington Times, 2017). By 2016, the House had voted to eliminate funding for Planned Parenthood 8 times, once making it through the Senate only to be vetoed by President Obama – the first time anti-abortion legislation had reached the President’s office in nearly 40 years (Vox, 2017).

In addition to his national-level goal to eliminate abortion, Pence continued to eliminate state-provided funding to Planned Parenthood of Indiana after being being elected Governor in 2013. State funding for Planned Parenthood fell from a total of $3.3 million in 2005 to $1.9 in 2014 forcing the closure of 5 Planned Parenthood of Indiana locations (Scottsburg, Madison, Richmond, Bedford, and Warsaw locations), none of which even provided abortion services, but did provide STI testing. The closure precipitated an outbreak of HIV and Hepatitis C in Scott County (Huffington Post, 2015).

In 2013, Vice President Pence signed legislation that prohibited doctors from prescribing RU-486 to women through telemedicine, necessitating in-person consultations with a physician at one of Indiana’s 12 abortion clinics, as well as requiring women to receive ultrasounds prior to their abortion and sign in writing if they do not wish to see the images or hear the heartbeat (Reuters, 2013). In 2014, Pence signed into law a bill that barred insurance plans from covering abortions except in the case of rape, incest, or threat to the woman’s health as well as made public the names of physicians who provide abortions, placing them at an increased risk of harassment or violence. In 2015, Pence signed another law that required facilities that perform more than five abortions per year meet requirements for “ambulatory surgical centers” which would be cost-prohibitive for the majority of these facilities, thus forcing their closure (Rewire, 2014).

HEA 1337

In 2016, a piece of legislation known as HEA 1337 was introduced and passed with much controversy. HEA 1337 is the among the most restrictive abortion pieces of abortion legislation in the country. The law made national news, spawned protests, and drew ire from abortion-rights supporters.

HEA highlights:

HEA 1337 timeline:

The language of the bill itself was vague, eliciting questions from the Indiana State Department of Health, Planned Parenthood, and other abortion providers regarding the intricacies of maintaining compliance, specifically regarding the disposal of fetal remains (Nuvo, 2016).

On June 30, 2016, a federal judge placed an injunction upon HEA 1337, preventing the law from going into effect. Judge Tanya Pratt stated the law would likely be found unconstitutional as it places an undue burden on women seeking abortions. In addition, the law does not recognize a fetus as a person, meaning there is no legal basis for the requirement of disposal of fetal remains by cremation or funeral (Indianapolis Star, 2016).

Indiana University also filed an additional lawsuit against the law’s prohibition of the sale or transfer of fetal tissue, citing their use of aborted or miscarried fetal tissue to research various conditions including autism and Alzheimer’s disease (Indianapolis Star, 2016).

Chapter 7: Cost of problem / Cost of solution

The cost of reduced access to abortion and reproductive health services can be difficult to assess, but this remains clear: the policies mandated by HB 1337 and other measures designed to restrict abortion unduly target minorities and low-income individuals (Nuvo, 2016b). While the fetal remains mandate places the burden of disposal upon the provider, this will increase provider costs, which may lead to these expenses being passed on to the patient. The requirement to receive in-person counseling and an ultrasound 18 hours prior to the appointment mean women potentially must take an additional day off work if they are employed, find childcare for any current dependents, and cover transportation and related costs in order to complete this requirement. Given the geographical distance some women may need to travel, this could potentially require them to pay for overnight lodging, as well.

On a broader level, providing abortions and other reproductive services for women would ultimately save taxpayer dollars. Planned Parenthood offers cost-effective care when compared with other government-funded providers. Additionally, research has shown that spending on contraception and family-planning services pays off over time. The Guttmacher Institute estimated in 2010 that every dollar spent in this category saves taxpayers $7.09 in Medicare costs by avoiding having to fund future prenatal care, birth, and health care for the infant’s first year of life (Guttmacher Institute, 2016). Despite this, then-Governor Pence used a total of $4.5 million from the Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) program to award a contract to anti-abortion organization ‘Real Alternatives’, whose mission “does not include funding for or the referral or advocacy of contraceptive services or drugs.” (Indi Star, 2015).

The proposed budgets that eliminate the use of federal Title X funding would primarily affect Planned Parenthood. These funds would still be available to health care facilities – just as long as they did not provide abortions. Patients covered under Medicaid and Title X would be forced to use these other clinics, who typically charge more for the same services, costing the government more money. Because Planned Parenthood is such a large organization, they are able to keep their costs down by contractual and bulk purchasing, something smaller clinics are not able to do. According to numbers provided by the Guttmacher Institute, shifting contraceptive care from Planned Parenthood to other clinics would cost the government an additional $174 million per year (Slate, 2011).

Colorado provides an interesting case study in the benefits of providing contraceptive care. In 2009, the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (DPHE) created the Colorado Family Planning Initiative (CFPI) that provided funds, training, and operation assistance to its family planning clinics that receive federal funds. In addition, this program provided grants to offer clients free access to long-acting, reversible contraceptives (LARC), tubal ligations, and sterilizations. The program was funded initially from a $23 million dollar private donation, with funding added by the state. The results of this program are impressive. Teen birth rates fell by 40% and teen abortion rates fell by 35%. Abortion rates among those aged 15-19 fell by 42%. 99% of teen moms who received an IUD before leaving the hospital after their first birth were not pregnant again within two years. DPHE also found that the birth rate for Medicaid-eligible women ages 15 to 24 significantly decreased from 2010 to 2012, resulting in an estimated savings in Medicaid birth-related costs of between $49 million and $111 million (OLR Research Report, 2015).

Chapter 8: Evaluating Prevention or Intervention

Given the existing research, it seems clear that the best solution to prevent abortion is to provide accurate sexual health education and increased access to contraception and family planning services. The Guttmacher Institute found that majority of women who obtained abortions were of lower levels of education while women who were least likely to have an abortion had higher levels of education. It can be concluded that individuals with higher levels of education generally have a higher income and therefore better access to contraceptives (2010). By requiring medically-accurate comprehensive sexual education to students in public schools, people of all education levels would have a greater chance of preventing both unplanned pregnancies and abortion.

Social stigma plays a factor in access to abortion services as well, so Planned Parenthood started the #ShoutYourAbortion campaign. This campaign gives people a space to share their stories and allows others to feel supported in their decision to choose an abortion. The website includes stories ranging from encouragement to choose whatever is best for one’s own life and health to personal accounts of the process of receiving an abortion. The site advertises itself as an open space to share stories and experiences rather than an environment for debate (Shout Your Abortion, 2017).

Chapter 9: Policy Challenges and Recommendations

It would stand to reason since research has shown that providing adequate and appropriate funding for family planning services and contraception would decrease rates of both teen pregnancy and abortion, those with a moral opposition to the procedure would support these measures politically. This, however, is generally not the case. Likely, the only way to be heard by those who support restricting access to abortion would be to emphasize the economic benefit to offering preventative services.

References

Basset, L. (2015, March 31). Indiana shut down its rural planned parenthood clinics and got an HIV outbreak. The Huffington Post. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/03/31/indiana-planned-parenthood_n_6977232.html

Boonstra, H. D. (2016). Fetal tissue research: a weapon and a casualty in the war against abortion.

Guttmacher Institute. Retrieved from https://www.guttmacher.org/gpr/2016/fetal-tissue-research-weapon-and-casualty-war-against-abortion

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). Abortion surveillance. Retrieved from

https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/65/ss/ss6512a1.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014). Reproductive health data and statistics. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/data_stats/

Crockett, E. (2014, April 4). Indiana governor signs abortion insurance cover ban. Rewire. Retrieved from https://rewire.news/article/2014/04/04/indiana-governor-signs-abortion-insurance-coverage-ban/

Donovan, M. (2017). In real life: federal restrictions on abortions and the women they impact.

Guttmacher Institute. Retrieved from

Dube, N. (2015). Colorado’s Family Planning Initiative. OLR Research Report. Retrieved from: https://www.cga.ct.gov/2015/rpt/2015-R-0229.htm

Guttmacher Institute. (2017). An overview of abortion laws. Retrieved from https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/overview-abortion-laws

Guttmacher Institute. (2017). Induced abortion in the United States. Retrieved from

https://www.guttmacher.org/fact-sheet/induced-abortion-united-states

Guttmacher Institutue. (2017). Maps of access to abortions by state. Retrieved from

https://fivethirtyeight.com/datalab/maps-of-access-to-abortion-by-state/

Guttmacher Institute. (2016). Publicly funded family planning services in the united states. Retrieved from https://www.guttmacher.org/fact-sheet/publicly-funded-family-planning-services-united-states#13

Guttmacher Institute. (2017). State facts about abortion: Indiana. Retrieved from

https://www.guttmacher.org/fact-sheet/state-facts-about-abortion-indiana

Gutett, S. (2013, April 2). Indiana house passes bill aimed at limiting the use of abortion pill. Reuters. Retrieved from http://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-abortion-indiana-idUSBRE93200A20130403

Hoosier Abortion Fund. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://alloptionsprc.org/our-services/hoosier-abortion-fund/

Indiana State Department of Health. (2014). Terminated pregnancy report. Retrieved from

https://www.in.gov/isdh/files/2014_TP_Report_7.1.15_FINAL_(with_additions_7.8).pdf

Jones, R., Finer, L. and Singh, S. (2010). Characteristics of U.S. Abortion Patients, 2008. [pdf] The Guttmacher Institute, p.7. Available at: https://www.guttmacher.org/report/characteristics-us-abortion-patients-2008 [Accessed 25 Apr. 2017].

Kane, P., Rucker, P., & Farenthold, D. A. (2011, April 9). Congress agrees to eleventh-hour budget deal to avert government shutdown. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/reid-says-impasse-based-on-abortion-funding-boehner-denies-it/2011/04/08/AFO40U1C_story.html?utm_term=.88e9a360524d

Kliff, S. (2011). Pence’s war on planned parenthood. Politico. Retrieved from

http://www.politico.com/story/2011/02/pences-war-on-planned-parenthood-049609?o=1

Kliff, S. (2017). Mike pence launched republicans’ war on planned parenthood. Vox. Retrieved from

http://www.vox.com/2016/7/14/12189446/mike-pence-planned-parenthood

Kurtzleben, D. (2015). Fact check: how does planned parenthood spend that government money.

NPR. Retrieved from

Marcotte, A. (2011, March 28). Why fiscal conservatives should embrace planned parenthood. Slate. Retrieved from http://www.slate.com/articles/double_x/doublex/2011/03/why_fiscal_conservatives_should_embrace_planned_parenthood.html

National Abortion Federation. (2017). History of abortion. Retrieved from

https://prochoice.org/education-and-advocacy/about-abortion/history-of-abortion/

NUVO Editors. (2016, March 24). After Pence signed HEA 1337, women’s rights in Indiana are dead. NUVO.(4 part series) Retrieved from http://www.nuvo.net/news/social_justice/after-pence-signed-hea-women-s-rights-in-indiana-are/article_0e27cf1a-00b9-5dfb-b6f3-316ffc3ab452.html

Obos Abortion Contributors. (2016, May 18). History of abortion in the US. Retrieved from

http://www.ourbodiesourselves.org/health-info/u-s-abortion-history/

Richardson, B. (2017, March 28). Pair who secretly filmed planned parenthood facing 15 felony charges. The Washington Times. Retrieved from http://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2017/mar/28/david-daleiden-sandra-merritt-charged-filming-plan/

Rudavsky, S. (2015). State awards $3.5 million contract for anti-abortion agency for pregnancy services. Indianapolis Star. Retrieved from http://www.indystar.com/story/news/2015/10/13/state-awards-35-million-contract-anti-abortion-organization-pregnancy-services/73819882/

Safe abortion: technical and policy guidance for health systems. (2012). 2nd ed. [ebook] World Health Organization. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/70914/1/9789241548434_eng.pdf [Accessed 26 Apr. 2017].

Schorge, J.O., Schaffer, J. I., Halvorson, L.M., Hoffman, B. L., Bradshaw, K. D., & Cunningham, F. G. (2008). First-Trimester Abortion. Williams Gynecology (1 ed.). McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 978-0-07-147257-9.

Shout Your Abortion. (2017). Retrieved from https://shoutyourabortion.com/

The White House. (2017). Vice President Mike Pence. Retrieved from https://www.whitehouse.gov/administration/vice-president-pence

US Department of Health and Human Services. Title x family planning. Retrieved from

https://www.hhs.gov/opa/title-x-family-planning/about-grant-policies/index.html

Wang. S. (2016) Judge halts Indiana’s new abortion law. The Indianapolis Star. Retrieved from http://www.indystar.com/story/news/politics/2016/06/30/judge-grants-preliminary-injunction-indiana-abortion-law/86556662/

You have to be 100% sure of the quality of your product to give a money-back guarantee. This describes us perfectly. Make sure that this guarantee is totally transparent.

Read moreEach paper is composed from scratch, according to your instructions. It is then checked by our plagiarism-detection software. There is no gap where plagiarism could squeeze in.

Read moreThanks to our free revisions, there is no way for you to be unsatisfied. We will work on your paper until you are completely happy with the result.

Read moreYour email is safe, as we store it according to international data protection rules. Your bank details are secure, as we use only reliable payment systems.

Read moreBy sending us your money, you buy the service we provide. Check out our terms and conditions if you prefer business talks to be laid out in official language.

Read more