Outsourcing Continuing Airworthiness Management activities is a benefit or a risk? Does EASA need to change the CAMO rules?

Under current legislation, Commission Regulation (EU) No. 1321/2014, both air carriers and commercial air transport operators have to develop their own Continuing Airworthiness Management Organisation which has the purpose of managing the tasks and activities associated with the continuing airworthiness of the fleet. Moreover, if the operator is deciding to outsource continuing airworthiness management tasks and activities, it will be limited and subject to the European Competent Authority approval from where the air carrier or the commercial air transport operator was registered. To put it in another way, the operator will be limited when outsourcing continuing airworthiness management tasks or activities.

This dissertation aims to investigate and evaluate the risks and benefits of outsourcing an airline or commercial air transport operator’s continuing airworthiness management activities and tasks. Based on this, an outsourcing decision model is developed which has the scope to help the operators on deciding whether it is beneficial to manage the continuing airworthiness tasks and activities in house or to outsource a part of them. In addition, this dissertation will analyse the regulations governing the continuing airworthiness to see if the European Aviation Safety Agency has to create a more flexible environment for airlines and commercial air transport operators for managing the continuing airworthiness. Consequently, the Notice of Proposed Amendment 2010-09 developed by the European Aviation Safety Agency will be analysed. The NPA 2010-09 proposes that air carriers or commercial air transport operators are offered the choice to outsource all continuing airworthiness tasks and activities to an approved stand-alone Continuing Airworthiness Management Organisation and in this instance the operator is not required anymore to develop its own CAMO.

By choosing the structured interview as a research method, the researcher is looking to explore concepts, ideas and interpretations from the perspectives of the respondents that are experienced within the field of study and are knowledgeable about this topic. The purpose of interviewing industry experts is to gather primary information which is to offer a better understanding and an industry overview of the topic being analysed in this dissertation.

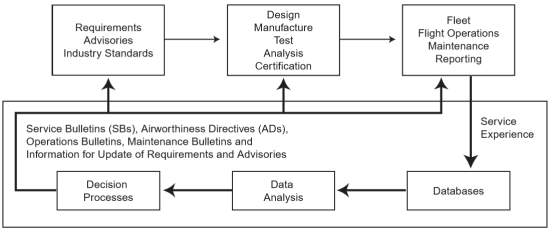

Figure 3.1: Continuing Airworthiness Process

Figure 3.2: EASA Initial and Continuing Airworthiness Regulation Structure

Figure 3.3: Part M in Relation to Maintenance of Aircraft

Figure 4.1: Traditional Airline Business Model

Figure 4.2: Virtual Airline Business Model

Figure 4.3: Aviation Business Model

Figure 4.4: Important information needed by the subcontractor to carry out maintenance planning

Figure 4.5: communication between CAMO, contracted Part 145 and subcontracted party

Figure 4.6: Possible choices for a CAT/licensed air carrier to ensure continuation of the aircraft airworthiness

Figure 4.7: Forces driving the change of the legislation governing continuing airworthiness

Figure 4.8: Rational and systematic approach to outsource CAM tasks and activities

AD = Airworthiness Directive

AMC = Applicable Means of Compliance

AOC = Air Operator Certificate

ARC = Airworthiness Review Certificate

C of A = Certificate of Airworthiness

CACE = Continuing Airworthiness Control Exposition

CAM = Continuing Airworthiness Management

CAME = Continuing Airworthiness Management Exposition

CAMO = Continuing Airworthiness Management Organisation

CAT = Commercial Air Transport

CDL = Configuration Deviation List

EASA = European Aviation Safety Agency

EU = European Union

GM = Guidance Material

ICAO = International Civil Aviation Organisation

MEL = Minimum Equipment List

MP = Maintenance Programme

NAA = National Aviation Authority

NPA = Notice of Proposed Amendment

PICAO = Provisional International Civil Aviation Organisation

SARP = Standard and Recommended Practice

SB = Service Bulletin

TC = Type Certificate

TDO = Type Design Organisation

Table of Contents

1.3.1 Aim of this dissertation

1.3.2 Objectives of this dissertation

2.1 Difference between qualitative and quantitative research

2.2.1 Interview as a research method

2.2.3 Ethics when conducting interviews

2.2.4 The interview protocol and process

2.3 Analysis of the interviews

2.4 Primary research limitations and challenges

3.1 From airworthiness to continuing airworthiness concept

3.2 Continuing airworthiness under ICAO

3.3 Overview of continuing airworthiness under EASA

3.4 Responsibilities of an operator and overview of Part M Sub-part G

3.4.2 Application for CAMO approval

3.4.3 CAMO facilities and personnel requirements

3.4.4 Quality system and classification of findings

3.4.5 Documentation, record retention and continuation of approval

3.4.6 Continuing airworthiness management tasks and CAMO privileges

4.2 Outsourcing an airline’s CAMO activities

4.2.1 Requirements of subcontracting continuing airworthiness tasks

4.2.2 What a CAMO can outsource and typical subcontracting arrangements

4.2.3 Communication between CAMO and subcontracted party

4.3 Changing CAMO rules – NPA 2010-09

4.3.1 Factors driving the change of continuing airworthiness regulation

4.3.4 Measures to eliminate any non-compliance when contracting all CAM tasks

4.3.5 Changes brought by NPA 2010-09 to Part M

4.3.6 Industry opinion with regard to the outsourcing of CAM activities and tasks

4.4 Decision model to outsource CAM tasks and activities

Continuing airworthiness is an important aspect of the commercial aviation industry because this concept is enhancing safety by ensuring that operated aircraft for commercial reasons have to be always in an airworthy condition. In the European Union (EU) any licenced air carrier or commercial air transport (CAT) operator registered in one of EU’s member countries has to comply with the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) regulations. Under Commission Regulation (EU) 1321/2014 a licenced air carrier or CAT operator has to develop an internal Continuing Airworthiness Management Organisation (CAMO) department which has to manage the continuing airworthiness management (CAM) tasks and activities that keeps the aircraft airworthy. The air carriers or CAT operators can outsource those CAM tasks and activities however, it is limited. EASA took the initiative to develop the Notice of Proposed Amendment (NPA) 2010-09 which proposes that airlines shall have the option to outsource all CAM tasks and activities. This NPA is still active and under discussions.

The core questions investigated in this dissertation are: is the outsourcing the CAM tasks and activities a benefit or a risk for airlines and CAT operators? Does EASA need to change Part M to make the continuing airworthiness legislation more flexible for commercial aviation? Therefore, the objectives of this dissertation are to determine if the outsourcing of CAM tasks is a benefit or a risk and to investigate if EASA has to change CAMO rules. Another objective is to develop an outsourcing decision model which will potentially help the air carriers and CAT operators.

The first chapter includes information about the hypothesis of this dissertation, its aim and objectives, research questions, background and potential challenges. In addition, the first chapter includes a brief description of how primary and secondary research will be gathered. In the second chapter it is discussed in detail the research methodology and method selected to gather information for primary research. Also, this chapter contains information on how the primary research was conducted and how the information was analysed. The third chapter is part of the literature review and is describing the continuing airworthiness concept. Also, third chapter provides an overview of how the continuing airworthiness is regulated under EASA. Moreover, the main focus of the third chapter is to identify the responsibilities of the operator and provide an overview of the Annex I Sub-part G of Commission Regulation (EU) 1321/2014. In the final chapter the author is discussing what CAM activities and tasks can be outsourced by a licensed air carrier or commercial air transport operator. In addition, this chapter outlines the idea behind the NPA 2010-09 and its purpose. Furthermore, at the beginning of the chapter the outsourcing in aviation is briefly discussed and at the end of it, the outsourcing decision model based on an economic model is developed and explained.

Continuing airworthiness is one of the most important key contributors to enhancing safety in commercial aviation. Continuing airworthiness[i] comprises from key maintenance tasks and activities which ensure that the aircraft will continue to operate in safe conditions during its operating life. Under the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA), any European Union (EU) licensed air carrier[ii] or commercial air transport (CAT) operator[iii] must have their own Continuing Airworthiness Management Organisation (CAMO), as per Commission Regulation (EU) No. 1321/2014[iv] Annex I. The purpose and objectives of a CAMO department is to keep the aircraft airworthy during its operating life. Some of the in-house CAMO activities of a licensed air carrier or CAT operator can be outsourced to an independent approved CAMO company. Although the CAMO activities that can be outsourced are limited, some airlines have different views about outsourcing and this might depend on what kind of business model the airline is operating.

Recently, there have been initiatives made by EASA to change the regulatory framework governing CAMO through the Notice of Proposed Amendment (NPA) 2010-09[v] which is questioning if it is possible that licensed air carriers or CAT operators can outsource all CAMO’s activities. However, no consensus has been reached over NPA 2010-09 which is still being debated. Being able to outsource CAMO activities and tasks may help start-up and established airlines to avoid the financial burden through outsourcing the CAMO department and pay more attention to their core business and competencies. Moreover, independent approved CAMO companies will not only be fully contracted by leasing companies but also by licensed air carriers and CAT operators that wish to outsource all CAMO tasks and activities. Therefore, the option of being able to outsource all CAMO activities and tasks will create a flexible solution for licensed air carriers and CAT operators and this may allow them to focus more on their core business and competencies to maximise profit.

Is outsourcing Continuing Airworthiness Management activities and tasks a benefit or a risk?

Does EASA’s legislative framework governing CAMO need to be changed?

The primary aim of this dissertation is to investigate and evaluate the benefits and risks of outsourcing CAMO activities and, based on this, to create an outsourcing decision model regarding continuing airworthiness activities. The secondary aim is to assess the opinions of different areas of the commercial aviation industry to see if EASA has to change the continuing airworthiness rules to create a flexible environment from which the aviation industry in the EU can benefit as a whole.

The first objective is to determine what are the benefits and risks of outsourcing continuing airworthiness activities. This will require a good understanding of EASA regulatory framework needed in particular, the Annex I of Commission Regulation (EU) 1321/2014 including any relevant Guidance Materials and Acceptable Means of Compliance. Also, industry opinions will be used to understand better the risk and benefits of outsourcing CAMO activities.

The second objective is to find out what will be the impact of outsourcing all CAMO activities in case EASA will supersede current continuing airworthiness rules and to what extent the aviation industry will benefit from this.

The third objective is to develop a continuing airworthiness outsourcing decision model for CAT operators and air carriers.

During a recent work experience I had the opportunity to take an internship with the CAM department of an aero-club. All CAMO activities were done in-house and nothing was outsourced to any independent organisation. When new services such as supplemental type certificates and CPCP programs had to be developed it was taking a long time and a lot of resources to do it especially that the aero-club owned an impressive fleet of gliders, aerobatic aircrafts and lightweight aircrafts. Sometimes not having the expertise in house means that time and resources are required to develop specific services. In addition, recently I had the opportunity to work in an independent CAMO which was dealing mainly with large airplanes in transition from one operator to another. However, most of the work generated for this independent CAMO was coming from aircraft leasing companies. Also, studying extensively in the Aviation Technology degree about EASA’s regulatory framework, I have started to focus on the continuing airworthiness legislation. Thus, being exposed to both independent and in-house CAMO gave me the idea of choosing this topic as a main research subject for this dissertation.

More information on challenges encountered during this research can be found in chapter 2.4 Primary research challenges and limitations.

Primary research will comprise of interviews/ questionnaires which will be addressed to airlines (both legacy and low cost carriers), independent CAMO companies and Competent Authorities. Primary research may also be under the form of analysing both qualitative and quantitative information made available. More details on primary research methods and methodology can be found in second chapter.

Secondary researchwill comprise of EASA regulations governing continuing airworthiness such as Annex I to Commission Regulation (EU) No. 1324/2014, NPA No. 2010-09 and International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO) Annex 6[vi] Part I and Annex 8[vii]. In addition, library resources, journal articles, internet resources and any relevant conference proceedings. Using secondary research materials, a critical literature review will be used to evaluate in greater detail why and why not to outsource CAMO activities.

Three options are identified in relation to outsourcing CAMO activities and those are: keeping CAMO activities in house, outsourcing partially CAMO activities (as reflected by the current Commission Regulation (EU) No. 1324/2014) or fully outsourcing the CAMO activities (if NPA 2010-09 will be adopted by European Commission to supersede current legislation). The options can be used in conjunction with a SWOT/Risk analysis to develop a conceptual outsourcing model for continuing airworthiness activities.

The qualitative research examines and takes into consideration experiences, attitudes and behaviour (Dawson, 2002, p. 14). The data or information gathered in a qualitative research is mainly qualitative in character (Saldana, 2011, p. 3) and uses research methods such as interviews or focus groups for primary research (Dawson, 2002, p. 14). Through a qualitative research, the researcher is aiming to gain a better understanding of the selected topic to be investigated by collecting data from other individuals’ experiences (Blair, 2016, p. 56). This type of research will require few people to take part in the research, however the contact with them will last longer (Dawson, 2002, p. 14).

Comparatively, the quantitative research will always generate statistics by using large-scale survey research and through research tools like structured interviews and questionnaires. To gather data for a quantitative research more people are involved and the contact with those people might be shorter when comparing with the qualitative research (Dawson, 2002, p. 15). In a quantitative research, the researcher will measure the relationship, which is the basis of predictions, between a dependent or outcome variable and an independent variable (Blair, 2016, p. 52). Furthermore, it is acknowledged that the researcher can achieve a combination of both qualitative and quantitative research. This is known as triangulation and some researchers claim that is a good approach for a thesis as the strengths and weaknesses of both qualitative and quantitative research are somehow balancing each other (Dawson, 2002, p. 20).

Providing that the researched topic is narrowed and focused on a specific area of study, the qualitative research was selected to be the main methodology framework of this dissertation. Moreover, the researcher chose the qualitative research because it is important to understand interviewees’ knowledge and their experiences. On the contrary, if the researcher was to select a quantitative research this could have been a constraint to find out qualitative answers for the core questions (Savin-Baden and Major, 2013, pp. 5-7). To find out the answers for the core questions, the researcher has to approach specific individuals who are working in the field of the studied topic and have experience within the field of study. Furthermore, by employing a qualitative research, the researcher will make the decision of what to be included or excluded in the research, what are the research questions and who are the participants. Consequently the qualitative research is a flexible research methodology framework where the boundaries can only be created by the researcher (Savin-Baden and Major, 2013, pp. 11-2). In addition, the main advantage of employing a qualitative research is that the research methods can be defined in the early planning stage. Therefore, the researcher becomes more focused and will know precisely what will be the most appropriate way to gather information for the research (Dawson, 2002, p. 33).

The research methods are tools used by researchers to collect primary information. The major research methods are focus groups, questionnaires, participant’s observation and interviews. The focus groups method involves a moderator and a number of individuals discussing a particular topic. The moderator’s role is to ask questions, mediate the group conversation and make sure that this is not deviated from the topic under discussion (Dawson, 2002, pp. 27-38). On the other hand, questionnaires are associated with quantitative research through which a scholar is looking to gather measurable data which is presented in a numerical format (Blair, 2016, p. 52). Different from focus groups and questionnaires as research methods, the participant observation method is the research tool through which the scholar wants to notice and have a deeper understanding on what is happening in a specific culture without interacting with it (Dawson, 2002, pp. 27-38). In contrast, the interview research method is one of the most common tools used to gather primary research information when the scholar is undertaking a qualitative research. Dawson identifies three different types of interview research methods: unstructured, semi-structured and structured interviews (Dawson, 2002). Because the researcher approached the qualitative research for this dissertation, the research tool used to collect data for primary research is the interview method (more details in subchapter 2.2.1).

Interview is one of the main methods used to gather information and data in a qualitative research. Interview is defined by Savin-Baden as being a conversation between two persons where the interviewer asks questions and the interviewee answers them. The purpose of the interviewer is to obtain in-depth information shared by the interviewee from it is own experience and perspective (Savin-Baden and Major, 2013, pp. 358-68).

The main advantage of the interview is that the researcher can adapt it while interviewing individuals. Through an interview concepts, ideas and interpretations can be explored whereas by carrying a questionnaire similar information cannot be gathered. Moreover, by carrying interviews, the feelings and motives of the person interviewed can be investigated. This is where a questionnaire will fail to record such information because through interviews ideas and concepts can be clarified or further developed. The down side of the interview method is that it is time-consuming and only a small number of people can be interviewed while compared to a higher number of respondents when selecting the questionnaire as a research method. In addition, the interview can be influenced by personal feelings and opinions and there is always the threat of biasing. As the information obtained is qualitative in nature it might be a challenge to analyse it. Similarly to a questionnaire, it is really important when the researcher is formulating the questions which are to be addressed to the interview participants (Bell and Waters, 2014, p. 178).

There are three common types of interviews: unstructured, semi-structured and structured interviews. By choosing the unstructured or in depth interview the researcher will look to achieve a better understanding of the researched topic through the perspective offered by the interviewed participant. The interviewee is allowed to talk freely and the interviewer has to keep the directional influence at minimum by asking as fewer questions as possible. The advantage of this type of interview is that it is easy to manage. However, as the interviewer has a lower interaction in the conversation it may become difficult to remain quiet. The interviewer has to stay focused and make sure that the participant is not changing the subject of the topic. In addition, unstructured interviews produce a huge amount of data which may be difficult to analyse (Dawson, 2002, pp. 27-8). On the other hand, a semi-structured interview requires the researcher to follow a set of questions, but during the interview additional questions may arise from the conversation. In general the main questions asked during the interview tend to follow an order. To allow the interview’s participant to express its opinions freely the questions are usually open-ended (Savin-Baden and Major, 2013, p. 359). The structured interview is discussed in detail in the next subchapter (2.2.2 Structured interviews) as the researcher chose this approach to collect information for primary research.

A structured interview requires the researcher to follow a particular set of questions that are to be asked in each interview. Although most of the questions asked are closed type questions, sometimes the researcher has a tendency to formulate the questions as open-ended. The structured interview is the research tool selected for this dissertation as it is considered to be the most suitable qualitative research method. Through a structured interview, the researcher is trying to minimise the variation in questions. Moreover, one advantage of the structured interviews is that the interviewer avoids to upset the conversation and opinions exposed by the interviewee. Also, by asking all participants similar questions, common information is collected and this is making easier for the researcher to analyse and compare the information provided by each participant. This particular research method can be used only if the researcher has a good understanding of the topic. Usually this is achieved by carrying a literature review of the topic and based on this the questions are structured for the interview. One disadvantage of the structured interview is that the questions prepared by the researcher may limit and restrict the investigation of issues that were not identified by the researcher when the questionnaire was developed (Savin-Baden and Major, 2013, pp. 358-9).

The researcher has to make sure that there is no legal boundary breached while carrying out the primary research. For this reason a good approach was followed as per Bell and Waters (2014) which points out that it is really important to let the participants know what the research is about and why they were chosen to be interviewed. Equally important is to let the participants know about the interview process and for what the information acquired during the interview is going to be used for. Therefore, each participant received a document before they confirmed their availability for the interview. The document entitled “Dissertation interview” contains details about the researched topic, objectives of the research, general ground rules to be agreed and questions asked during the interview (for more details on ‘Dissertation Interview’ document see Appendix IX). All participants have been given equal opportunity to enquire if there is any information or statement in the ‘Dissertation Interview’ document needed to be clarified. This was to make sure that the participants fully understood what the research is about and what will be the questions that the researcher will focus on during the interview. Also, this approach was followed to eliminate any uncertainty caused by participants withdrawing from the interview stage based on misleading or ambiguous interview process and/or questions.

To ensure that the participants know about their rights and identify the interviewee responsibilities, some ground rules have been implemented in the interview process document. The ground rules had to be agreed between respondents and researcher in order to protect any party’s position. All participants had the opportunity to remain anonymous. Also, they were asked if they wanted to be dissociated with the company/corporation they worked for. As part of analyzing the interviews, the researcher decided to protect the respondents’ identity (for more details see “Interview duration, place and ground rules” section from Dissertation Interview document attached in Appendix IX).

The participants were approached through email to see if they wished to take part in the research and consequently interviewed. After they confirmed and accepted to be interviewed, the dissertation questionnaire was sent to them. This was to ensure that the respondents will fully understand the researched topic and also know what questions are going to be asked during the interview. Each participant had the right to request clarification in case there was an identified ambiguous process step or question.

To ensure the participation at the interview the location, date and time of the interview was decided upon the preference of respondents. At the start of the interview, each respondent was asked if the interview can be recorded and if they need any other clarification about the interview process or questions asked. In addition, each interviewee was asked if they would like to remain anonymous or not associated with their company they work for. This was to protect them in case the information gathered thorough the interview contained sensitive information about them or the company/corporation they work for. At the end of the interview the participants were asked if they would like to receive a transcript of the interview. This was to reflect a transparent analysis of what exactly they said and stated during the interview.

The analysis of the interviews is based on evaluation and examination made on each interview transcript which are attached in Appendix X. By analysing the first question it was found out that it is not a huge cost incurred on airlines setting their own CAMO but is important to mention that managing the CAM tasks and activities is only a labour intensive job and it hugely depends on the pay rates. This is one of the criteria which will influence an operator to outsource certain CAM tasks and activities and this is where the operator cannot compete with independent CAMOs offer, as they can perform the tasks cheaper. Furthermore, the outsourcing will hugely depend on airline’s fleet size, complexity of operations [flying short, medium or long haul routes], how many aircraft types are operated and to what extent the airline is unionized (in this case outsourcing being the last option). One of the airlines interviewed was outsourcing one of their aircraft type CAM tasks to a well-known technical services provider and the benefit of this was the knowledge pool that the subcontractor has. The CAMO manager stated that the subcontractor helps the airline to keep the aircraft in-service and without a third party input developing the in-service experience might be a challenge.

When the interview participants were asked what are the risks associated with outsourcing CAM tasks and activities, the following potential risks have been highlighted:

All potential risks mentioned above can be prevented by having strong contracts in place and a sufficient level of oversight. A good oversight will comprise from implementing audit processes to assess the performance of the contracted party and to make sure that the contracted work [CAM tasks/activities] are carried out. In addition, the operator’s audit programme shall ensure that the contracted party has proper procedures and resources to manage the contracted CAM tasks/activities. To ensure a good communication between both parties, proper meetings have to be arranged and a good reporting system should be developed. To ensure a ‘good visibility’ for the aircraft managed by a contracted third party and to eliminate the likelihood of ‘cross contamination’ to occur, both parties shall either work on the same IT system/platform or the contracted party has to be fully trained to work as per the operator’s requirements and standards. A very important key point to mention is that the operator has to do his due diligence before contracting any organisation to manage CAM tasks/activities. This is mainly to ensure that the third party provider is a viable company, with a long term commitment and that will not go out of business causing the airline (or aircraft managed) to be grounded.

The fourth question asked, revealed that there is not a high risk between outsourcing CAM tasks/activities to either an approved stand-alone CAMO or a non-approved technical services provider organisation. In both cases it is a must that the operator’s CAMO has to review the contracted work performed by the third party to make sure the operator’s standards are followed and that the contractual agreements are followed. The required level of oversight is usually greater when CAM tasks/activities are outsourced to a non-approved organisation (not CAMO approved). Also, the work performed by a non-approved organisation has to be reviewed and certified by an operator’s CAMO while CAM tasks/activities carried out by an approved CAMO are certified. Additionally, the independent CAMOs are seen as a better choice as they reached a European standard by being approved by a particular NAA. A CAMO already went through the NAA’s audits while a non-approved technical services provider is not regulated. However, there are situations where non-approved organisations are as good as a CAMO and possibly more specialized than a CAMO, having that knowledge pool and in-service experience for certain aircraft types. Consequently, either a poor CAMO provider or a poor non-approved technical services provider will not last long on the market. Ultimately, the outsourcing decision stands with the operator who has to do their due diligence. It is a very common approach that the airlines will look to outsource CAM tasks and activities to reputable organizations disregarding that they are approved or not. Moreover, those reputable organisations are unlikely to go out of business as they have a massive financial back-up and a strong position in the market.

From the fifth and sixth questions it is concluded that the proposed amendment NPA 2010-09 will potentially eliminate the higher risks associated with sub-contracting a non-approved organisation. As the airlines will have the choice of outsourcing all CAM tasks and activities to an approved stand-alone CAMO, certain non-approved organisations providing technical services may look into getting a CAMO approval. This will not only raise the industry standard but will potentially bring them more customers. One of the respondents is stating that “if the non-approved organisation becomes approved by changing their processes to good processes it is an improvement and this will make a difference”. On the other hand there is a demand from the EU aviation industry that EASA has to offer the choice for airlines to outsource all of their CAM tasks and activities. This demand is mainly driven by airlines where the outsourcing is their business model, airlines that have a small fleet (including operations) and airlines which are looking to establish on the market (including start-up airlines). Another advantage is that multiple airlines making part of the same parent company will be able to use a centralized CAMO through which all airlines will share certain CAM services and build up the in-service experience. One potential issue with providing this option to airlines is how the airlines and CAMOs will control the accountability. Another challenge will be to ensure, manage and maintain a good relationship between both parties which will be vital for aircraft continuing airworthiness.

Regarding the development of the outsourcing decision model one interviewee advised that this should be based on an economic model. Before the outsourcing decision will take place the operator has to ask itself why there is a need to take into consideration the outsourcing option. As previously stated, the decision will be based on the airline business model, fleet size etc. Also, the operator has to take into account the competent authority’s acceptability for a third party to be contracted to manage operator’s CAM tasks. After this, the operator has to clarify what CAM tasks and activities have to be outsourced and this has to be supported by arguments which will contribute to outsourcing decision.

As mentioned previously in subchapter 2.2.2 one limitation of using the structured interview as a primary research method is that that the questions prepared by the researcher may restrict the investigation of issues that were not identified in the secondary research and when the questionnaire was developed. For instance, from one interview carried with one respondent, it was highlighted that there is the need to develop legislation to control and standardize those technical services companies and lessors managing engines. At the moment when an engine comes off the wing independent technical services providers can do all CAMO type functions but their work is not certified. The airline is generally re-analysing all information prepared by those independent companies in order to certify the status of the engines. Therefore, there is a scope for EASA to develop regulations to cover those organisations looking to obtain a dedicated CAMO approval for components, engines and APUs. This area is not well developed and regulated at the moment, and the engines, APUs and other aircraft components are more valuable than the airframe itself.

One challenge was that only five out of nine participants expressed their interest to be interviewed. The researcher targeted participants from airlines’ CAMO department, independent CAMOs and competent authorities in order to gather information with the scope to achieve a full industry overview for the researched topic. However, there were no participants interviewed which were involved or worked for a competent authority. Moreover, it was desirable to interview participants employed in all airline business models but only employees from a legacy and a regional airline took part in the interview. Under those circumstances, a full industry overview cannot be provided, as the primary research information cannot be analysed from different perspectives (from each airline business model and competent authority’s point of view). Another challenge encountered by choosing to research this topic is that there are no previous studies, dissertations or other academic papers to discuss about the Continuing Airworthiness Management Organisation concept and gaps within the EU legislation governing this concept.

The author Fillip de Florio (2016) defines the airworthiness concept as being “the possession of the necessary requirements of an aircraft to fly in safe conditions, within allowable limits”. In this simplified definition three important key elements can be identified: possession of necessary requirements, flying in safe conditions, and allowable limits. The possession of the necessary requirements refers to the standards and regulations which are followed to build, design and test an aircraft, its parts and components. In addition, the safe conditions makes reference to those conditions free of causing any harm, injury, illness to aircraft passengers or damage to a property or environment. Furthermore, the allowable limits means that the aircraft is flying within its approved flight envelope for which it is designed to operate into. Therefore, each aircraft type has specific structural load factors and speed ranges that cannot be exceeded and is designed to fly in specific types of operations. (Florio, 2016).

In contrast with the airworthiness concept, continuing airworthiness is regarded to be a set of processes which maintain or restore an airplane, its systems or parts of a system to a standardised airworthiness process established by a type design organisation. Sometimes from a safety perspective, it is identified that the original standards are not stringent enough when the operator may encounter issues such as systems malfunctions and faults while the aircraft is in service. For this reason, service life expectation of the aircraft may be reduced or extended if adequate corrective actions are taken. Therefore, the continuing airworthiness process carried out continuously during the aircraft life cycle may adjust the aircraft service life values and design standards. Equally important, is the revision of civil aviation regulations, standards and recommended practices based on findings while the aircraft is in service (Enders, Dodd, and Fickeisen, 1999).

The continuing airworthiness process comprises from three key steps: generating a database, analysing data and decision process. The generation of database is done through gathering data from operators based on service experience. After that, data is analysed and often compared to the original certification process and results. The final step is the decision making process carried out by either an accident investigation authority or a national aviation authority and certification authorities. Furthermore, the manufacturers and operators of the aircraft, parts and components will be part of the decision making process (see Fig. 3.1) In all steps difficulties may be encountered because the acquisition of human and computer resources information may be insufficient to form a consistent database which makes it difficult to generate a database and analyse it (Enders, Dodd, and Fickeisen, 1999).

|

You have to be 100% sure of the quality of your product to give a money-back guarantee. This describes us perfectly. Make sure that this guarantee is totally transparent.

Read moreEach paper is composed from scratch, according to your instructions. It is then checked by our plagiarism-detection software. There is no gap where plagiarism could squeeze in.

Read moreThanks to our free revisions, there is no way for you to be unsatisfied. We will work on your paper until you are completely happy with the result.

Read moreYour email is safe, as we store it according to international data protection rules. Your bank details are secure, as we use only reliable payment systems.

Read moreBy sending us your money, you buy the service we provide. Check out our terms and conditions if you prefer business talks to be laid out in official language.

Read more