Yes, the hybrid approach of integrated low cost-differentiation strategy can result in a competitive advantage when executed well. Firms operating in the upper right quadrant of the Integration-Responsiveness (IR) Grid face high pressures for both global integration and local responsiveness. As more companies turn to global markets for growth, which necessitates cost efficiency gains through standardization and at the same time requires adapting to local conditions because of diversity of principles, practices, agents, and consumer preferences, the transnational strategy provides a means to configure and coordinate value chain activities to simultaneously manage these competing pressures.

The transnational strategy employs a sophisticated value chain that is configured to simultaneously tap location economies through concentration and is dispersed sufficiently, subject to minimum efficiency standards, to satisfy local preferences. The firm coordinates value creating activities by championing “global learning” that emphasizes learning from various environments and then integrating and deploying the knowledge throughout its global operations.

The transnational strategy supports optimization of global efficiency and local effectiveness and leverages learning that drives innovations throughout the corporation. The learning also enables managers to respond to changing business environments quick to reorient activities without the imposition of added bureaucracy. On the other hand, a successful implementation of transnational strategy is difficult to execute, poses coordination challenges, and is prone to shortfalls. Also, the strategy imposes excessive costs associated with managing a network organizational structure, a geocentric staffing framework, installing appropriate coordination and control mechanisms, and developing an organizational culture that accepts decision-making ambiguity and promotes multicultural teambuilding. And worse still, aiming for the transnational strategy and falling short can result in the “stuck in the middle” syndrome. These firms suffer from a lack of coherent strategy and struggle to compete in the marketplace.

There are many companies that have successfully evolved a transnational strategy either through necessity or through a Darwinian system of retaining what worked and rejecting what no longer worked. GE is one such firm that became global in the 1980s and pursued a vision of boundary less company that embraces an open environment, seeks and shares learning regardless of origin, and finds and develops the right people for the right job to lead businesses worldwide that suggests a transnational strategy. As a result, GE saw increased efficiencies, improved productivity and effectiveness, cost reductions, and refined account management practices. Its “global learning” initiatives spread the lessons learned and deployed best practices corporate wide and became one of the most respected and profitable companies in the world. However, in the last few years, GE has struggled to keep up with technology disruptions, slowing economies, and increasing protectionism worldwide. In recent years, its stock price has underperformed, and the company suffered major investment losses. And this year, the stagnated growth and investor pressures to rethink strategy led to the ouster of Jeffrey Immelt, the star CEO who took the reins from Jack Welch in 2000. This goes to show that even the most sophisticated companies with a proven track record of successes have trouble sustaining an effective transnational strategy to deliver consistent returns.

At the country level, Porter’s national diamond framework stipulates that four features – demand conditions, factor conditions, related and supporting industries, and firm strategy, structure, and rivalry – are important for global competitive advantage and seeks to explain why some countries develop and sustain competitive superiority in certain industries. One example that illustrates such a pattern is the prestige enjoyed by Germany’s auto manufacturers in the performance/sports car segment.

Factor Conditions: Thanks to its metal-working traditions, Germany has historically benefitted from availability of highly skilled labor for industrial production. Germany is also renowned for its engineering universities and government support for scientific research. This provides an abundant skilled human resource that is necessary for sophisticated industries such as high-performance automobiles and machinery. In addition, Germany has vast iron ore resources – a key ingredient used in the production of high quality steel used in high-end car manufacturing. Germany is also the financial powerhouse of continental Europe and firms enjoy access to low-cost capital needed for investment in industrial innovation and product development.

Demand Conditions: Germany has a large domestic population of over 80 million people and is centrally located to serve a large customer base in Europe. Historically, Germany has had a fascination with automotive industry starting with the invention of the four-stroke internal combustion engine by pioneers such as Nikolaus Otto and Karl Benz in late 1800s. The subsequent “motorization” policy by the Nazi regime created domestic demand for German automobiles. The technological advancements in post-WWII Germany further helped develop a savvy customer base that appreciated technologically superior and well-engineered products. Today, the EU market and global brand reputation ensure high demand for German sports car products from manufacturers such as Mercedes-Benz, BMW, and Audi. Furthermore, the Autobahn highway system with no speed limits in certain parts ensures a substantial home market customer base that enjoys powerful cars and helps the companies assess emerging buyer preferences to innovate and adapt quickly.

Related and Supporting Industries: Germany’s mature iron and steel industry that provided high-quality steel input employed in production of superior automotive engines and car components helped develop the car industry in the country. In addition, German auto companies have had access to a vast network of auto parts suppliers both at home and in neighboring countries. For example, BMW sources interior panels from Dräxlmaier Group, Steering columns, shock absorbers and suspension parts from Thyssenkrupp, brake calipers from Brembo, Drivetrain components from BorgWarner, etc. The presence of high quality competing suppliers and supporting industries enables German auto manufacturers to focus on their core competencies and outsource the rest helping them achieve cost effectiveness and strategic competitiveness.

Firm Strategy, Structure, and Rivalry: German companies tend to have hierarchical organization and management structures and top managers usually come from technical backgrounds. This management system works well for engineering-oriented industries such as automotive and complicated machinery that demand precision manufacturing, disciplined product development, and after-sales service. Also, the nature of capital markets where banks hold substantial share of equity in companies and focus on long-term appreciation means companies do well in mature industries and can escape the strong pressures for short-term gains at the expense of long-term health and sustainability. Finally, the presence of strong rivals in close proximity ensures continuous innovation and a persistent stimulating effect that results in a sustainable competitive advantage – both in home and international markets.

While the favorable conditions may have helped Germany develop a world-wide recognition of its auto industry and a competitive superiority, it should not be taken for granted. Increasing globalization brings new competitors who can overcome absence of favorable conditions at home by acquiring them in international markets. In addition, the increasing speed of technology change implies that the four facets of the diamond are more dynamic and international than ever before.

One key idea that I learned by doing the feasibility study project is that while it is more tractable and manageable to study and analyze the various environments – physical, political, cultural, economic, competitive, legal, and financial – facing a foreign investment decision separately, firms must bring all aspects together and look at the opportunity-risk tradeoffs in an integrated fashion to make the final go-no-go decision.

My team performed the feasibility study on Thailand to assess a foreign direct investment to exploit opportunities to acquire high quality coconut wax for use in the manufacture of natural wax candle products in the U.S. We assigned information gathering and analysis of various environments to individual team members to avoid duplication of effort and complete the tasks on time. Individually, our subjective assessment of each of the environments was that there are tremendous risks involved with the proposed FDI and that the risks potentially outweigh the growth opportunities for the company. However, once we pooled all the benefits and risks each of the environments offered and compared them with the risk-tolerance of the firm, the decision to go forward with the investment became clearer.

For example, the military involvement in Thailand’s political process poses high political instability risk, but at the same time the policies formulated by the junta government to combat corruption and increase business regulation transparency reduces the company’s risk of violating U.S. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act associated with Thailand’s culture of gift giving and bribery practices in business transactions. Another similar example is that Thailand is exposed to a wide-variety of natural disasters that increase supply disruption and raw material price volatility risks for the proposed FDI. However, the availability of cheap labor, abundant warehousing space, and a slew of tax and non-tax benefits for operating in the IEAT Free Zone at Lad Krabang in Bangkok enables us to maintain an excess inventory and cost-effectively mitigate most of the risk associated with raw coconut supply disruptions.

The key takeaway for me is that we should avoid assessing risks and benefits of each of the dimensions separately. A more meaningful approach is to pool all the benefits and risks and evaluate the total risk posed after considering potential risk mitigation activities and make a final go-no-go decision after weighing the total risk against both the strategic opportunities the FDI provides and the risk-tolerance of the firm.

The metaphor that I found most interesting is “The German Symphony”. In my previous job, having collaborated with a German engineering team for a design project, I now realize that the metaphor could have been immensely useful in understanding their perspectives on key issues and in improving communication clarity. With this new-found knowledge, I now believe that with an improved understanding of the German culture, I could have been more effective in work-place negotiations and avoided many of the gridlocks and frustrations we as a team faced on collaborative engineering projects.

The symphony’s positional arrangement reflective of compartmentalization of society, respect for privacy, and formality in business dealings explains some of the perplexing behaviors I encountered in the work-related dealings with my German-counterparts. As described in Gannon’s book, I found that my German co-workers would not inform me of their vacation plans and so missed important task-deliverables, which meant my peers and I took on the extra work to meet project deadlines. I also found that in design review meetings we spent significantly more time analyzing and arguing about the engineering details than we typically do for U.S. product design programs. Back then, I attributed the issues to language barriers and lack of understanding of corporate engineering best practices by the German engineers. Now, I realize the behavior is attributable to their risk-averse nature and a desire to understand opportunities and risks before fully committing to them. If I had understood such German business practices, I would have been better prepared by planning for vacation-related contingencies during the project scheduling phase and could have resolved interpersonal conflicts within the team much more amicably.

The precision and synchronicity aspect of the symphony that reflects Germans’ consciousness of time, directness in communication, and deductive style of scientific analysis towards problem solving helps me understand both my past errors and the approaches I could have taken to succeed in my negotiations and in reaching mutually acceptable agreements. I found that meetings initiated and led by my German counterparts tended to go long, delved into historical design changes, and emphasized logic and in-depth complex analysis, which ran counter to the U.S. team’s approach of using speed and simplicity to drive important decisions. In addition, there were times when the U.S. and German teams took opposing sides on key issues that resulted in delayed tasks because of differences in opinion and lack of trust. I now think that most of the issues could have been avoided had our team better understood communication preferences and differing approaches to decision making between the German and U.S. business cultures. In future dealings with German counterparts, I will better prepare by including ample detail in the discussion content, communicate it in a direct and respectful manner, and be persuasive by making principles and theory based arguments.

Analysts attribute the growth of globalization in recent times to these seven factors:

Opportunities

Globalization enables the world’s businesses to gain significant benefits in the areas of expanding sales, acquiring key resources, and reducing risk by engaging in international business. The rising middle class in emerging markets and increasing disposal incomes throughout the world in recent times implies that companies with international business activities now have access to a significantly higher number of potential customers than found in any single domestic market. By engaging in international business, the companies can spread their fixed costs over a larger number of units sold and as a result improve their profitability and competitiveness in their chosen industries. Many of the world’s largest companies such as IBM, Michelin, and Sony make over half their sales to customers outside their home markets.

Challenges

A company engaging in international business faces challenges in the physical, social, and competitive domains and some of those might require the firms to significantly alter the way they run their operations abroad. The physical and social factors include geographic influences, political policies, legal policies, behavioral differences, and economic conditions, while the competitive factors include product strategy, resource base and experience, and intensity of competition. For example, a U.S. company wanting to exploit sales opportunities in an emerging market, say China, will have to navigate a myriad of regulations concerning ownership, taxation, transfer pricing, local content requirements, employment and termination, IP and trademark protection, and foreign exchange transactions. For instance, local content requirements could force a company that traditionally relied on high quality suppliers in the home market for some key components to build factories in China and make them in-house, source them from a lower-quality supplier, or form a partnership with a local company. All these options increase cost of doing business and adversely impact profit margins and increase business risks.

Winners & Losers

Globalization has had different effects on different industries. Some industries saw their fortunes decline while others benefitted tremendously.

Industries such as the pharmaceuticals that rely on large investments in R&D to develop products, but have low barriers to entry in terms of manufacturing have lost as a whole. Globalization and offshoring to lower development/production costs resulted in transfer of manufacturing know-how to low cost countries and as a result the generics medicine market has exploded. Companies like Ranbaxy, Cipla and Teva produce enormous quantities of generic medicines at low cost while the big pharmaceutical companies that spent millions of dollars developing the formulations have incurred enormous costs in their efforts to enforce patent and market exclusivity rights. In addition, these generic drugs increasingly compete with branded drugs in developed nations and put a downward pressure on profit margins in the pharmaceutical industry. As a result, many pharmaceutical companies find it difficult to recoup sufficient returns from their R&D investments and are increasingly reluctant to fund large research projects to make new innovations in discovering treatments for complex and chronic diseases such as cancer.

On the other hand, industries such as luxury automobiles that have high brand differentiation are winners of globalization. Increasing global GDP and growing affluence in emerging markets because of globalization have created new markets for all the firms in these industries. Companies in these industries enjoy tremendous benefits such as increased sales, access to low cost resources, and reduced risk from market diversification. In addition, they escape the commoditization-trap that plagues other industries by marketing status and prestige associated with brand reputation.

The world’s first working Liquid Crystal Display (LCD) was built by George H. Heilmeier in 1964, the same year the plasma display panel was invented. In the 1970s and 1980s, LCD technology was used successfully in calculator displays and competed with plasma displays for portable computer displays due to their light weight and low cost. However, the refresh rates on LCD displays were too low to be useful for television application. In years that followed, the LCD TV industry closely followed the international product life cycle theory of trade.

Introduction (1980s – early 2000s)

The earliest commercially made LCD TV was the Casio TV-10 made in 1983 with a 67-mm screen size and was offered exclusively for the Japanese market. In the next few years, while a few other Japanese manufacturers such as Epson and Citizen offered a few competing products, Casio had a near-monopoly position and sold color LCD portable TV models such as Casio TV-1000, Casio TV-6100, and Casio TV-800 (see Figure 1). In 1990, Sony entered the mobile color TV market with the Watchman FDL-310 with an active LCD matrix technology in the entertainment electronics category (see Figure 2). In the mid-1990s, the innovations continued, and LCD technology was incorporated in high-end gadgets alongside FM/AM radio, portable loudspeakers, and incorporation of PAL and NTSC signal formats for worldwide early adopters. During this time the plasma displays outpaced LCD displays in performance and became the go-to technology for high definition TV gadgets. The early LCD TVs manufactured by Sony and Sharp cost $15,000 or more and were novelty items that served as status symbols for the wealthy.

Figure 1. Casio TV-1600 and Casio TV-800 models. Adapted from “The short history of Pocket-TV,” by Gunthor, F., 2005 (http://www.taschenfernseher.de/e-history.htm). In the public domain.

Figure 2. Sony Watchman FDL-310. Adapted from “The short history of Pocket-TV,” by Gunthor, F., 2005 (http://www.taschenfernseher.de/e-history.htm). In the public domain.

Growth (2004 – 2013)

The introduction of HDTV programming in Japan, US, and other industrialized nations in late 1990s and early 2000s produced a market for new television technologies such as LCD and plasma display that could take advantage of the wider 16:9 aspect ratio and clearer picture quality. During this time, the excessive cost and low refresh rates associated with LCD meant the traditional Cathode Ray Tube (CRT) technology maintained a large footprint in spite of its disadvantages, and plasma displays became the standard for HDTV sets.

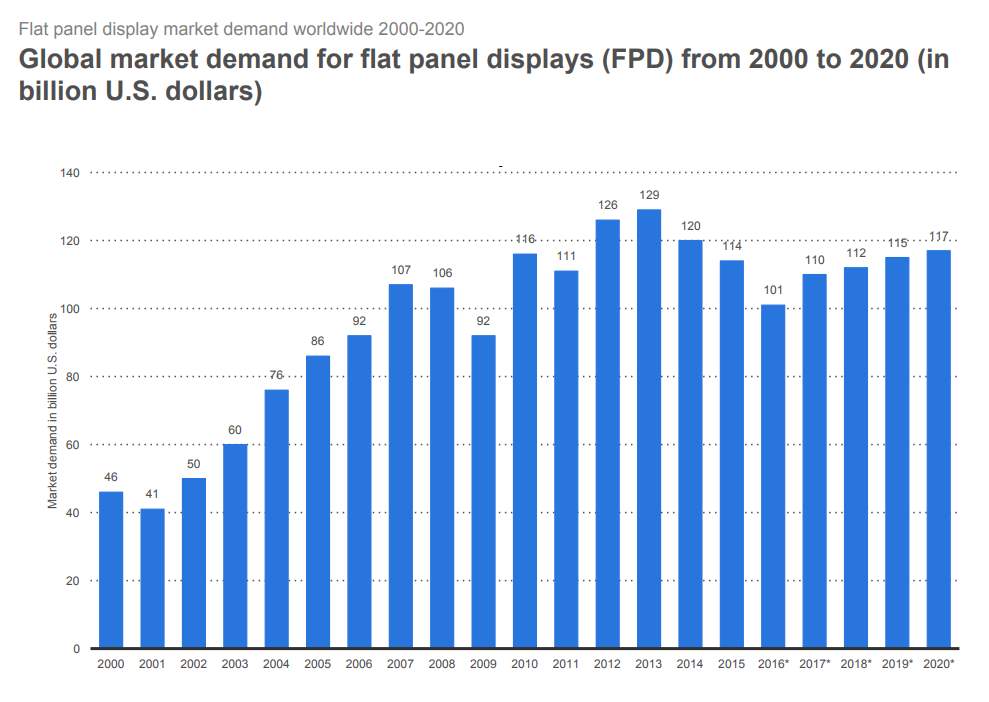

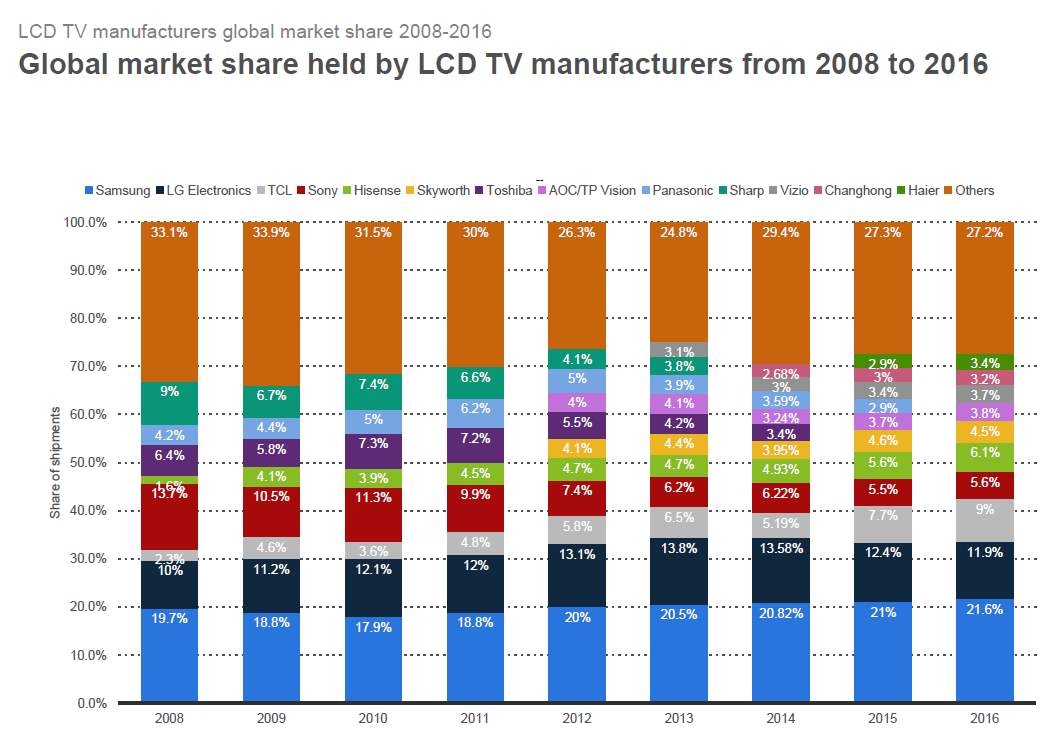

The situation changed rapidly with LCD technology achieving economies of scale in the smaller display sizes such as in laptops and inventions such as LCD Overdrive technology that made LCDs practical for television refresh speeds. By 2004, LCD TVs were competing with plasma TVs in 32” size class in terms of price and larger screen sizes above 42” were starting to become available. In 2007, for the first time LCD TVs outsold both CRT and plasma TVs in the developed markets such as the U.S., Japan, and Europe. Much of the growth in the flat panel displays in the years 2004 to 2013 (see Figure 3) is due to the market dominance of LCD TV technology and its ability to scale both up and down in size. During this period, as the number of competitors increased (see Figure 4) and as LCD TVs dominated the flat panel TV market in both the sub 30” size class as well as over 40” category, the prices dropped rapidly, and production methods became more standardized. In this stage, manufacturers used a combination of exports and local assembly operations in key markets such as the U.S. and the EU to exploit sales opportunities.

Figure 3. Global market demand for flat panel TVs. Adapted from “Statista dossier about television (TV) technology,” (https://www.statista.com/study/15703/tv-technology-statista-dossier/). In the public domain.

Figure 4. Global market share of LCD TV manufacturers. Adapted from “Statista dossier about television (TV) technology,” (https://www.statista.com/study/15703/tv-technology-statista-dossier/). In the public domain.

Maturity (2014 – present)

At the current time, the LCD TV industry appears to have entered the maturity stage. Since 2014, the demand for LCD TV units has stabilized in the industrialized world. Much of incremental growth in developed markets is now from feature advances such as ultra HD (4k and 8k), internet connectivity, 3D, and HDR technologies. On the other hand, manufacturers are experiencing strong demand in China, India, and other emerging markets and have begun shifting manufacturing and sales focus to those countries. For example, in Jan 2017, Sharp and Foxconn announced the construction of a LCD panel plant in India to exploit sales opportunities in the region. In 2016, while developed country markets had declining sales, India’s LCD TV market grew by over 18% with most of the demand coming from LED backlit LCD TV units in the sub 32” category due to their low power consumption and affordable price point.

Decline (near future)

Based on current trends in the TV industry and growth of other disruptive technologies that is changing the consumption habits, I expect LCD TV industry to transition into the decline stage in the next 10 years. New TV sets based on Organic Light Emitting Diode (OLED) technology promising better picture quality, lower power consumption, and more environmentally friendly manufacturing practices could easily push LCD TVs to extinction much the same way CRT TVs have become antiques in a span of few years. In addition, the new holographic technology and shifting media consumption behavior to mobile devices could mean TV sets and television programming may become relics of the past.

Therefore, in the near future, I think the LCD TV industry will strive to introduce new incremental innovations to maintain relevance and encourage consumers to replace their current TV sets to delay the decline stage for as long as possible. In addition, the falling prices and increasing commoditization would drive producers out of the LCD TV industry and into other promising opportunities such as newer TV technologies, mobile entertainment and virtual reality. A few low-cost producers would continue competing primarily on price for the remaining demand in the developing world.

The traditional theory of comparative advantage by David Ricardo seeks to explain trade patterns and products traded by theorizing that global trade is driven by countries specializing in what they can produce most efficiently. Implicitly, the theory advocates that differences in countries such as possession of different resources and different levels of productivity drives trade between them. The comparative advantage theory also makes several assumptions such as perfectly competitive markets, homogeneity of commodities traded internationally, full employment, economic efficiency as the primary goal, fair division of gains, negligible transportation costs, comparative advantage being static, and restricted mobility of resources, some of which may not be valid always.

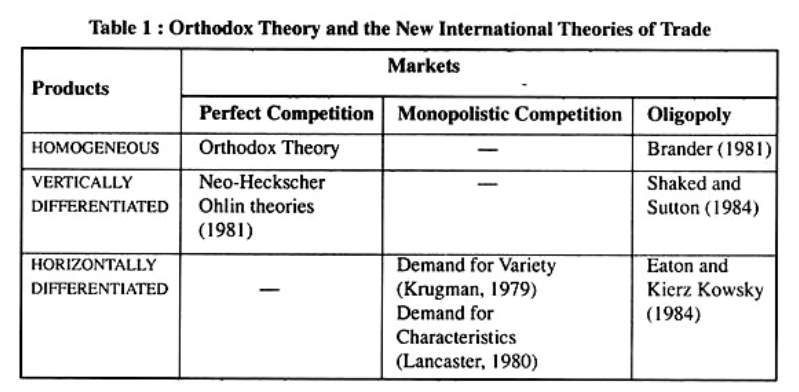

The new trade theories came into existence to explain observed phenomenon that ran counter to the traditional theories of international trade. There is not one “new trade theory” economic model, but several with different assumptions and results. However, there is one common feature shared by all “new trade theory” models, which is dropping the assumptions of perfect competition and product homogeneity. See Figure 5 for classification of trade theories/models based on the type of good and market form.

Figure 5. Classification of trade theories and their application. Adapted from “The New Theories of International Trade,” (http://www.economicsdiscussion.net/international-trade/the-new-theories-of-international-trade-economics/26942). In the public domain.

Paul Krugman starts with the observation that while old trade theories explain a lot of world trade, they also miss a lot such as trade between countries with similar climates and resources. His new trade theory postulates that substantial economies of scale and network effects determines international patterns of trade in key industries. Therefore, while the broad pattern of production in countries is determined by resources and climate, there is substantial additional specialization due to economies of scale, which in turn explains the presence of much more trade than would be expected from a purely resource-based theory.

The new trade theory with the assimilation of factor-proportions-based comparative advantage that explained inter-industry trade and specialization due to economies of scale and increasing returns to explain intra-industry trade offers an integrated look at world trade. The new trade theory with emphasis on economies of scale indicates that early entrants can become dominant firms in the market and enjoy large economies of scale leading to monopolistic competition as consumers seek variety and firms compete on branding or quality and not just price. It also means most lucrative industries will be in developed countries because they were the first to develop the industries and reached industrial maturity before other nations. While the new trade theory predicts big gains through trade liberalization, by relegating factor endowment to secondary status, it also suggests that governments have a significant role to play, especially in developing countries, in supporting the growth of key industries through tariff protections and subsidies for capital-intensive industries until they reach the maturity needed to exploit economies of scale.

Externalities to the Society

From the works of Adam Smith in the 18th century to the formation of World Trade Organization and liberalization of economies post WWII, free trade has slowly but surely won the support of economists and governments worldwide. The underlying notion is that when countries trade concentrating on goods in which they have a comparative advantage, everybody wins because more goods are produced on a per-resource unit basis and therefore consumers enjoy lower prices and higher standards of living. The new trade theory does not advocate protectionism, but by recognizing that economies of scale is a key factor in influencing trade, it gives credibility to the infant-industry argument by suggesting that the government might have a role to play in supporting key capital-intensive industries. The risks and externalities imposed on the society with such an approach are:

The World Trade Organization (WTO) is a global international organization founded in 1995 with 125 members as a successor to United Nations’ General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) to facilitate reciprocal trade negotiations and enforce trade agreements between member nations. The WTO adopted the principles and trade agreements reached under GATT but expanded its mission to include trade in services, investment, intellectual property, sanitary measures, plant health, agriculture, textiles, and technical barriers to trade. Today, WTO has 164 nations as members that collectively make decisions by consensus. The countries make decisions through various councils and committees such as the Ministerial Conference, the General Council, the Council for Trade in Goods, the Council for Trade in Services, and the Council for Trade-Related Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS). There are provisions for a majority vote in case of a non-decision and agreements must then be ratified by governments of member nations.

The Banana Dispute

One interesting dispute, called “the banana dispute”, between the EU and the U.S. representing its producers’ interests in Latin America was about EU’s preferential treatment of banana imports from Africa, Caribbean, and Pacific (ACP) countries in line with the Lomé Convention of 1975. In 1993, the European Commission adopted a Common Market Organization for bananas under which it allowed bananas from ACP countries to be imported at reduced tariffs and with preferential quotas. While the U.S. objected to the banana regime from the very beginning, the Latin American banana-producing countries of Colombia, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Nicaragua, and Venezuela first initiated GATT dispute settlement proceedings in June 1993 to which the EU responded by negotiating a “Framework Agreement” that raised non-ACP quotas and lowered in-quota tariffs on Latin American bananas.

The adverse impact of the banana regime and the Framework Agreement on US producers with operations in Latin America led them to file a petition with the US Trade Representative (USTR) in late 1994. Unable to reach a settlement with EU, the USTR joined by Guatemala, Honduras, and Mexico initiated a dispute settlement in the WTO against the EU in 1995. The WTO found the EU import regime to be illegal in 1997. After multiple scheme-revisions by the EU failed to be accepted by the U.S., in April 1999, the WTO authorized the U.S. to impose trade sanctions valued at $191 million on EU imports. The U.S. implemented this ruling by imposing 100% customs duties on several products from EU member states.

In the years that followed, the EU escalated the Beef hormone dispute, while the U.S. responded by using “carousel retaliation” provision to change the types of EU products targeted for trade retaliation. In addition, the 10 Latin American banana suppliers – Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Peru, and Venezuela – initiated eight separate WTO cases against the EU. An acceptable resolution was reached in 2009 under the Geneva Agreement on Trade in Bananas, under which the EU established a tariff-only banana regime with no special quotas and where the tariffs on Latin American banana imports are being gradually reduced over the period from 2010 to 2017. The agreement was finally ratified by all parties in 2012.

While the Geneva Agreement brought the “banana wars” to an end officially, it has multiple stipulations tied to Doha development agenda. As of 2017, the Doha Round has not gained significant traction and looks like it may never reach fruition. In the short-term, the WTO trade dispute resolution mechanisms on the banana issue seems to have been effective in resolving major disagreements and increasing trade-related cooperation between the EU and the U.S. backed Latin American nations with WTO most-favored-nation status. The long-term effectiveness depends on whether the parties can reach a satisfactory agreement on agricultural trade in general – assuming progress will eventually be made on the Doha development agenda.

A letter of credit is a bank letter guaranteeing that a buyer’s payment to a seller will be received on time and for the correct amount. The exporter receives payment only when the shipping document is accepted to have strictly adhered to the terms and conditions stipulated in the letter of credit.

A confirmed letter of credit is a type of letter of credit, which is guaranteed by a bank other than the issuing bank. The confirming bank, which is typically the seller’s bank, ensures payment if the buyer or the issuing bank are unable to honor the payment terms. A confirmed letter of credit is an important instrument of international trade and reduces the counterparty risk to sellers when dealing with clients in potentially unstable economic environments or if the issuing bank has questionable creditworthiness. Usually, the issuing bank seeks the confirmation of the L/C with a bank it already has a credit relationship with.

Example

Company X based in Georgia, U.S.A sells specialty candles and wants to import $100k worth of candles from Company Y that operates out of Thailand. This is the first order that Company Y received from X, and therefore is concerned about X’s ability to pay for the goods.

To address the issue, Company X applies for a letter of credit at Bank of Georgia, which indicates that Bank of Georgia guarantees the payment of $100k. Bank of Georgia, the issuing bank, sends the L/C to Siam Commercial Bank, the exporter’s advising bank, and pays a fee requesting that the L/C be confirmed, which guarantees that Company Y will be paid $100k in case Company X and Bank of Georgia are unable to honor the payment.

Once Company Y receives the confirmed L/C from Siam Commercial Bank, it ships the candles and receives shipping documents such as Bill of Lading from the shipping company. Company Y then submits the necessary documents that includes both shipping and supporting documents such as Commercial Invoice and Bill of Lading to Siam Commercial Bank and receives payment once the bank confirms all the terms and conditions have been met. Siam Commercial Bank forwards the documents to Bank of Georgia and requests reimbursement of $100k. Bank of Georgia hands the documents over to Company X in exchange for $100k payment and miscellaneous charges for its services. Company X uses the documents to clear the cargo through U.S. Customs at Port of Brunswick and transports the goods to its warehouse via truck.

Clearly, a confirmed L/C is a valuable instrument that reduces risk to both the seller and buyer in international transactions. The seller is assured of payment and can avail the convenience of dealing with only the advising bank. It also protects the buyer because the seller must submit documents that indicate the goods shipped meet all the contractual terms before getting paid.

Unilever is one of the world’s largest and leading fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) company with offerings of over 400 brands focused on health and well-being. The company employs about 170k people, operates in 100 countries and sells products in more than 190 countries worldwide.

Corporate International Strategy: Transnational

During the roughly 90 years of Unilever’s history, the company underwent multiple strategy shifts and in recent times settled on a transnational strategy to optimize worldwide integration and local responsiveness. With increasing globalization, intensifying competition in world markets, and consumer preferences converging in major categories like food, refreshments, home care, and personal care, the company faces increasing pressures to exploit economies of scale by standardizing products. At the same time, the unique cultural, legal, political, and economic conditions of the diverse markets Unilever operates in force it to design, make, and market products that respond to local preferences. The company responds to these competing pressures by following a transnational strategy and aims to offer low costs through efficient production, create unique value by differentiating capabilities from country to country, apply coordination methods to leverage core competencies, and learn systematically from various self-sufficient units and diffuse the knowledge throughout its global operations.

Organizational Structure: Global Matrix

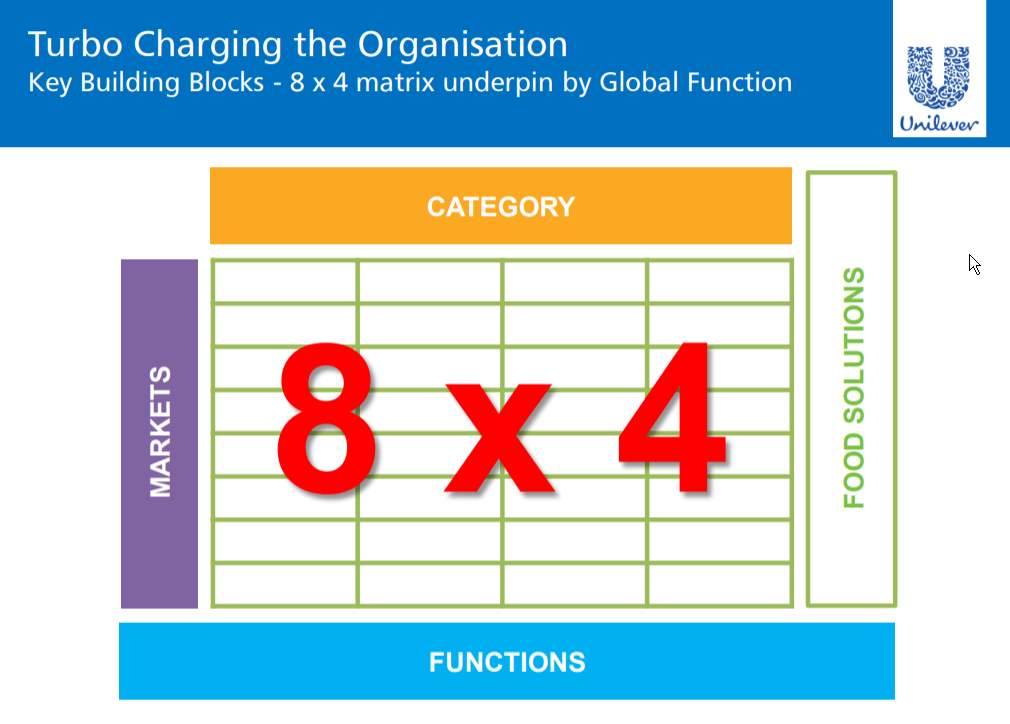

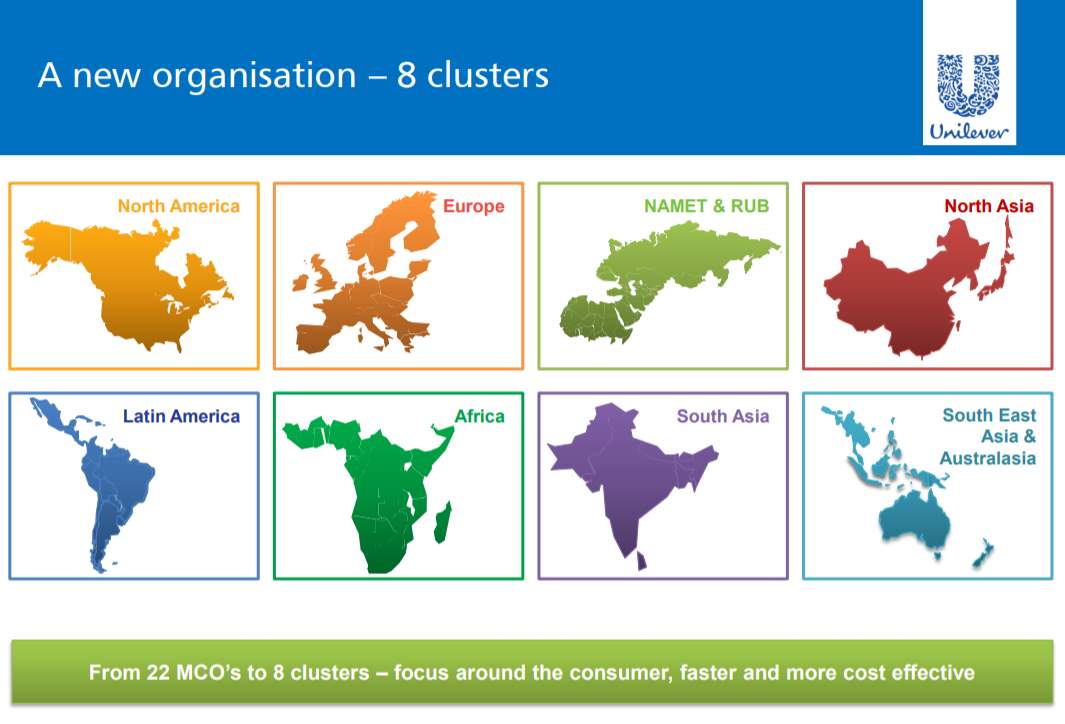

To align organizational structure with its transnational strategy, and to balance the centralization and decentralization needs, Unilever uses a global matrix structure based on four product categories and eight regional market clusters (see Figures 6). The four broad categories are personal care, home care, refreshment, and foods. The world regions are divided into eight clusters: North America, Europe, NAMET & RUB, North Asia, Latin America, Africa, South Asia, South East Asia and Australasia (see Figure 7). To reduce costs and increase operating efficiencies, all operating units in the world work with centralized global groups in the following functional areas: finance, R&D, HR, supply chain, marketing, and IT/enterprise support.

Figure 6. Unilever’s global matrix organizational structure. Adapted from “Unilever Investor Seminary,” (https://www.unilever.com/Images/2011-investor-seminar-2011-driving-towards-a-performance-culture-doug-baillie-chief-hr-officer_tcm244-422757_en.pdf). In the public domain.

Figure 7. Unilever’s eight regional clusters. Adapted from “Unilever Investor Seminary,” (https://www.unilever.com/Images/2011-investor-seminar-2011-driving-towards-a-performance-culture-doug-baillie-chief-hr-officer_tcm244-422757_en.pdf). In the public domain.

Furthermore, the “Unileverization” of all subsidiaries under the Unilever umbrella ensures that the company’s many scattered units share a common corporate culture focused on performance, quality, and efficiency and work cooperatively towards one shared vision.

Sustainable Competitive Advantage Level: High

Unilever’s strong brand recognition, diverse portfolio of brands, large geographic footprint, excellent R&D, leading position in emerging markets, improving efficiencies and product quality combined with the company’s ability to evolve its international strategy to align with packaged consumer goods industry’s changing strategic requirements implies Unilever has strategic fit and possesses high level of sustainable competitive advantage.

While the company has faced headwinds with slowing growth in foods and declining profit margins in home care product categories, the company is well-positioned to exploit growth opportunities in healthy and nutritional food segment and FMCG products in emerging economies. The company’s sharper international strategy and strong support for a transnational network through both its formal structure and informal exchanges between its various units ensure good ideas are transferred seamlessly and implemented quickly to drive future growth and profitability.

REFERENCES

Anushree, A. The new trade theories of international trade. Retrieved December 15, 2017, from http://www.economicsdiscussion.net/international-trade/the-new-theories-of-international-trade-economics/26942

Baillie, D. (2011). Unilever investor seminary. Retrieved December 12, 2017, from https://www.unilever.com/Images/2011-investor-seminar-2011-driving-towards-a-performance-culture-doug-baillie-chief-hr-officer_tcm244-422757_en.pdf

European Commission. (2000, July 5). The banana case: Background and history. Retrieved from http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2003/december/tradoc_114950.pdf

European Union. (2010, June 9). Geneva agreement on trade in bananas. Retrieved from http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2010:141:0003:0005 :EN:PDF

Huet, J. M. (2014, December 4). Driving profitable growth. Retrieved from https://www.unilever.com/Images/unilever-investor-seminar-2014-jean-marc-huet-introduction-driving-profitable-growth_tcm244-423104_en.pdf

Immelt, R. J. (2017, October). How I remade GE. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2017/09/inside-ges-transformation

Krugman, P. (2008, October 15). About the work. Retrieved from https://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2008/10/15/about-the-work/

Library of the European Parliament. (2013, April 22). Principal EU-US trade disputes. Retrieved from http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/bibliotheque/briefing/2013/130518 /LDM_BRI(2013)130518_REV1_EN.pdf

Maljers, F. A. (1992, October). Inside Unilever: The evolving transnational company. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/1992/09/inside-unilever-the-evolving-transnational-company

Maverick, J. B. (2016, March 29). Who are BMW’s main suppliers? Retrieved from https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/060115/who-are-bmws-main-suppliers.asp

Nikkei Asian Review (2017, January 14). Foxconn, Sharp mull LCD plant in India. Retrieved from https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/AC/Foxconn-Sharp-mull-LCD-plant-in-India

Patterson, E. (2001, February 27). The US-EU banana dispute. Retrieved from https://www.asil.org/insights/volume/6/issue/4/us-eu-banana-dispute

Pettinger, T. (2017, February 26). New trade theory. Retrieved from https://www.economicshelp.org/blog/6957/trade/new-trade-theory/

Porter, M. E. (1990, March). The competitive advantage of nations. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/1990/03/the-competitive-advantage-of-nations

Pritchard, J. (2016, November 18). How a letter of credit works. Retrieved from https://www.thebalance.com/how-letters-of-credit-work-315201

PR Newswire. (2017, June 19). Global luxury car market report 2017 – research and markets. Retrieved from https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/global-luxury-car-market-report-2017—research-and-markets-300475704.html

Young, J. (2017, February 21). Unilever’s organizational structure for product innovation. Retrieved from http://panmore.com/unilever-organizational-structure-product-innovation

You have to be 100% sure of the quality of your product to give a money-back guarantee. This describes us perfectly. Make sure that this guarantee is totally transparent.

Read moreEach paper is composed from scratch, according to your instructions. It is then checked by our plagiarism-detection software. There is no gap where plagiarism could squeeze in.

Read moreThanks to our free revisions, there is no way for you to be unsatisfied. We will work on your paper until you are completely happy with the result.

Read moreYour email is safe, as we store it according to international data protection rules. Your bank details are secure, as we use only reliable payment systems.

Read moreBy sending us your money, you buy the service we provide. Check out our terms and conditions if you prefer business talks to be laid out in official language.

Read more