LEADERSHIP CASE STUDY – A MODEL OF CRITICAL EVALUATION

CONTENTS

CRITICAL EVALUATION – INTRODUCTION AND EXPLANATION

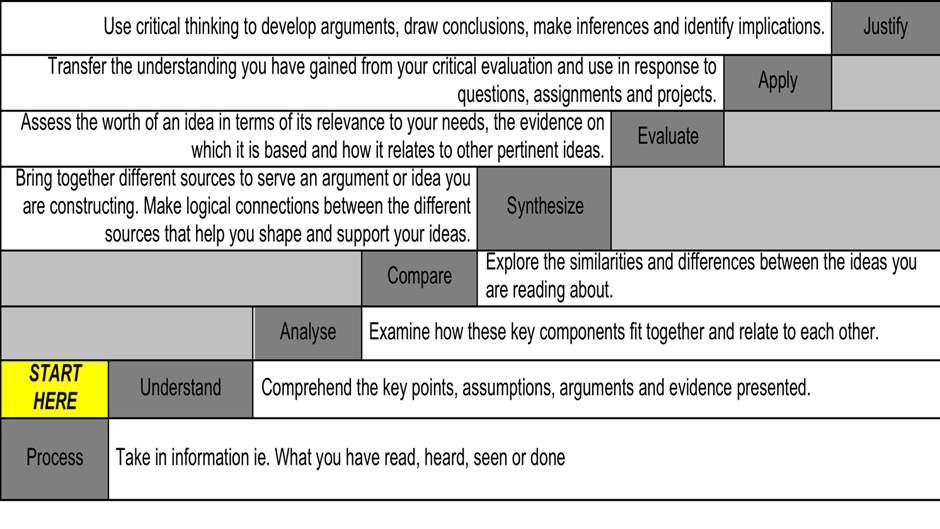

Diagram 1: The Open University’s ‘Critical Thinking Stairway’.

2.3 THE BRITISH ARMY LEADERSHIP MODEL

2.4 CRITICISMS AND WIDER APPLICABILITY

3. CASE STUDY – SERVANT LEADERSHIP IN THE BRITISH ARMY

3.3 THE BRITISH ARMY LEADERSHIP MODEL

3.4 CRITICISMS AND WIDER APPLICABILITY

The following research aims to benefit future final year students studying Leadership and Management. The assignment intents to test the following the learning outcomes of the module. The critical evaluation of different organizational contexts for leadership, management and development, as well as the critical evaluation of leadership, management and development in practice.

In addition following research aims to investigate how accepted models can be reviewed in a different context, facilitating critical analyses which may challenge accepted thinking (Bryman & Bell, 2015). The intent is to consider if and how a particular leadership style may deliver improved business results if applied in a different operating environment, closing with a relevant insight that appears to offer supporting evidence (Grint, 2005). However, given the length of the case study, the synthesis, evaluation and subsequent justification are only carried forward in outline and the intent is to encourage further critical evaluation (Open University, 2016).

Whilst it is probably relatively easy for the reader to appreciate the principles behind the servant-leadership style, it is the wider business/operating environment that introduces the intellectual challenge allowing pertinent arguments to be formed (Hanscomb, 2017). Linking the concept of leadership to the challenges associated with managing change and maintaining an enduring competitive advantage adds a further layer of synthesis (Kotter, 2010; Porter, 2004). It also demonstrates a willingness to challenge potential ‘structural’ constraints in how such topics are presented within academic texts and mainstream business discourse (Mullins & Christy, 2016; Williams, 2014).

The fundamental point of critical thinking is to effectively capture the reasoning that is applied in a range of contexts to both improve our ability to generate strong/valid arguments and to refine our ability to assess the strength and impact of the arguments presented by others (Hanscomb, 2017). In conducting any balanced evaluation, it is therefore important to understand the process and concept of reasoning in addressing problems, questioning the basis for our own beliefs and actions as well as being able to present (to others) why we hold such views and opinions (Williams, 2014).

Critical evaluation is therefore about applying reasonable, reflective thinking which is focussed on deciding what to believe or do – essentially reaching an end statement or opinion built on a review of evidence (Norris & Ennis, 1989). It therefore requires the ability to improve the quality of thought/thinking applied by applying an element of structure in order to impose an intellectual standard and rigour (Fisher, 2001). As well as the ability to collate, present and evaluate evidence, the willingness to identify the flaws presented in any argument – as well as any underlying assumptions or implied (and untested) statements upon which that argument may be built – is a core element of any critical evaluation (Williams, 2014).

If critical evaluation therefore requires the application of structured intellectual review in order to help develop and challenge any arguments presented, then it is appropriate to consider models and tools that can provide a rigorous analytical framework (Thomson, 2009). One such model is the Open University’s ‘Stairway to Criticality’ (2016) which suggests the following stepped approach:

(Open University, 2016)

From a consideration of the model outlined in Diagram 1, the following should be noted:

The target of critical thinking is to try to keep an ‘objective’ position. (Fisher, 2001). This mean that the reader must try and be aware of any presumptions about an argument. The researcher should always identify the drive of the data, analyse the material, compare and contrast different resources. (Williams, 2014). Furthermore the resources that the research is using should be trustworthy and reliable in order for the research to be respectable and critical.

In building our level of comprehension, it is essential to develop a knowledge base that can differentiate between the nature of the information and the value that is applied to it (Fisher, 2001). This requires the willingness and ability to select the best evidence available with a careful consideration of its authenticity (undisputed origin), validity (relevant to the arguments under review), current (not dated – still valid) and reliable (trusted) (Cottrell, 2011). For those undertaking qualitative research, this often involves a particular challenge in differentiating between fact and opinion and if the nature/size of any sample gives a true reflection of majority or minority views and understanding (Bryman & Bell, 2015).

Only by conducting an effective comparison and analysis of the arguments and ideas presented can the knowledge base of the researcher be developed and key assumptions, exclusions and causal explanations identified (Hanscomb, 2017). The aim must be to consider the argument from a range of differing perspectives, ensuring that accepted (and personal thinking) is challenged where appropriate (Williams, 2014). Even apparently clear, undisputed facts can lead to a range of causal explanations e.g. an argument could be framed that blames poor street lighting for increased traffic accidents at night (poor visibility) or it could be stated that it reduces traffic accidents (as drivers take greater care (Fisher, 2001). Capturing such interpretations is essential if subsequent ideas and concepts are to be effectively evaluated.

In capturing and considering different perspectives, models, concepts and theories, any researcher will find some arguments more or less compelling and this will be shaped by their own viewpoint(s) and the context of the case they are seeking to build (Thomson, 2009). The final proposition made should present a synthesis of mutually supporting perspectives whilst recognising the contrary arguments that may exist (Cottrell, 2011). Any subsequent evaluation needs review and challenge any remaining assumptions, consider relevance and meaning (i.e. ‘this is relevant because’) and confirm if the reasoning applied supports the conclusions being made (Fisher, 2001).

Having taken such a stepped approach, it is then possible to return to the core questions presented (the context set for the critical thinking applied) and transfer the knowledge and insight captured in a way that is relevant and useful (Hanscomb, 2017). However, when reaching and presenting conclusions – even if they are only recommending further investigation – it is important to ensure that the arguments made are robust, evidence/knowledge based and rooted in critical thinking (Williams, 2014). Care must be taken not to present findings built on equivocation and ambiguity (using peripheral evidence to create a proposition), false dichotomies (only exploring binary arguments), perfectionist fallacies (e.g. ignoring ‘better’ because ‘best’ can’t be reached) and circular arguments (ignoring alternative positions or only seeking evidence supporting a particular perspective) (Hanscomb, 2017).

The British Army’s attitudes and approach to leadership are presented as a case study which can illustrate the application of critical thinking and evaluation in developing an argument (Thomson, 2009). The organisation is often cited as a particular example of effective leadership practices within academic papers, but such arguments are often rooted in untested assumptions and potentially circular arguments i.e. the British Army is ‘good’ and respected within society, so therefore its leadership is ‘good’ (Grint, 2005; Hanscomb, 2017).

The analysis is conducted in the context of the servant-leadership model which is used as a developmental framework within British military training and educational institutions (Royal Military Academy Sandhurst, 2017). Whilst this provides a clearly bounded entity for analysis, as a hierarchical and functional organisation which meets its objectives through the effective deployment of people the observations made are likely to have wider interest and applicability (Mullins & Christy, 2016). Change management and transformation remain particular business challenges and an examination of how the British Army balances leadership, organisational culture and a regulated environment against the need to maximise flexibility in the face of any enemy has the potential to capture key lessons for the corporate sector (Latawski, 2011).

The case study seeks to examine what the British Army have done to create a responsive and flexible leadership approach (Schedlitzki & Edwards, 2014). Their model appears to provide people with the skills and autonomy needed to decide how they choose to achieve objectives rather than simply follow direction, rules and procedures (Grint, 2005).

(In reviewing the case study, its relevance to the Open University’s ‘Critical Thinking Stairway’ is shown in footnotes in order to maintain a distinction between the case study arguments (Harvard referencing) and an explanation of the critical evaluation adopted (Open University, 2016)).

CASE STUDY – SERVANT LEADERSHIP IN THE BRITISH ARMY

Leadership is essentially a process whereby the leader is able to influence others to achieve a common goal (Northouse, 2010). In order to successfully exert this influence, how the leader interacts with the people around them – often described as the styles and attributes of leadership – is often a critical factor (Yukl, 2010). Leadership is seen to be vested in the person (how their character and personality shape their effectiveness), embodied within processes (reflecting the culture and context being faced), built around position (organisational hierarchies) and achieving results (a successful leader gets things done) (Grint, 2005).

there is general consensus that it is built around the need to exercise power and manage power relationships (Mullins & Christy, 2016). This power can be built on information (the leader possessing knowledge others do not), reward and/or coercion (people depend on the leader), in legitimacy (their right to lead is recognised by others), expertise (seen as superior) or referent (the leader is a source of respect and admiration (Iszatt-White & Saunders, 2014). The effectiveness of a leader is further shaped by the organisational culture that exists and how they exercise power within that construct (Kakabadse, Ludlow & Vinnicombe, 1988).

The British Army’s approach to leadership is often cited as being distinctive and a model that should be emulated by more mainstream corporate entities (Yukl, 2010). The British Army’s leadership model is therefore examined in order to consider what potential lessons can be developed.

Whilst different models, theories and styles of leadership are stated to exist (Schedlitzki & Edwards, 2014),

Definition of Servant Leadership

“Servant leadership begins with the natural feeling that one wants to serve, to serve first. Then conscious choice brings one to aspire to lead…The difference manifests itself in the care taken by the servant – first to make sure that other people’s highest priority needs are being served’’ Greenleaf (1970)

The core academic texts appear to distinguish five key leadership styles :

(Iszatt-White & Saunders, 2014; Yukl, 2010)

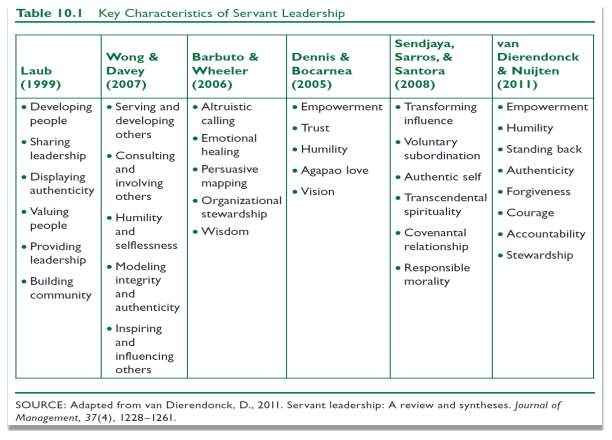

Alongside ethical leadership (doing the right things in the right way for the right reasons) and spiritual leadership (generating meaning, engagement and involvement, servant leadership – the ability to empower and direct others whilst giving clear direction and showing an element of humility – is regarded as a particular manifestation of the authentic leadership approach outlined (Manning & Curtis, 2009). However, the British Army have developed a different perspective, considering servant-leadership to be the core of any successful/enduring system of leadership that is able to quickly respond to changes in the operating environment (Joint Warfare Publication 0-10, 1999; Army Staff Officers Handbook, 1999) .

The Army’s approach is more of a cultural philosophy, rooted in the ethical responsibility of leaders, an innate almost spiritual understanding of people and values built around honesty, respect, trust and the development of talent (Mullins & Christy, 2016). The British military constantly strive to apply the hard-won lessons gained in conflict and – surprisingly for many external observers given the nature of the organisation – one of the most important observation has been the danger of relying on directive or autocratic leadership approaches (Latawski, 2011).

An over-prescriptive or leadership approach leads to military units being unable to respond quickly, efficiently and effectively to new threats, emerging tasks and fast-changing scenarios. The traditional (World War 1 and early World War 2) view of the strong, autocratic leader commanding from the centre of the battlefield actually creates a culture lacking in challenge, innovation and agility (Campbell, 1997). The British therefore seeks to adopt the ‘auftragstaktik’ (literally mission-tactics) approach learned from their early losses against the German Army in World War 2 (Campbell, 1997).

On the battlefield, emerging, (potentially favourable) situations will never be fully exploited if subordinate leaders have to seek new instructions or follow rigid, established procedures (Heifetz, Grashow & Linsky, 2009). Consequently, soldiers are encouraged to work in support of the mission rather than follow set orders, giving the freedom to adapt and exploit any evolving situation providing that they still carry out the mission concept outlined by their superiors (Matthews & Laurence, 2012).

Given the increasing complexity of the defence environment and significant resource constraints, subordinates must feel comfortable challenging the status quo without believing that they may risk their own position in the organisation (Yukl, 2010). The military therefore expend considerable effort in providing development interventions that provide soldiers with the knowledge, skills and support needed to strike an appropriate balance between following orders and exercising independent judgement (Price Waterhouse Change Integration Team, 1996; Joint Warfare Publication 0-10, 1999).

Servant-leadership as a military philosophy is therefore seen as essential if military forces are to remain cohesive and combat effective under such circumstances (army Staff Officers Handbook, 1999). It ensures that no gap between the leaders and the led can emerge – leaders remain visible, sharing the hardships and dangers faced by their staff when it is appropriate to do so (Latawski, 2011, Royal Military Academy Sandhurst, 2014).

Ultimately, servant-leadership provides one of the key determinants for military success – flexibility. This is seen as being a core principle of war-fighting and comprises agility, responsiveness, resilience, acuity and adaptability) (Latawski, 2011).

Within the corporate business environment, leaders are increasing required to act as agents of change. They are expected to be strategic thinkers, but also demonstrate an ability to create a shared vision that drives success and create the culture required to maintain that success (Yukl, 2010). As this is founded in the need to respond to a rapidly changing operating environment, then adopting/adapting the British Army’s approach to leadership could deliver an enduring competitive advantage (Porter, 2004).

However, the British Army has been criticised for its continuing inability to adapt to the cultural and social changes present within the community from which it recruits, leading to significant capability shortfalls (BBC, 2015a: Farmer, 2017). The leadership have also been challenged for being too flexible and responsive when faced with Government demands, allowing imposed resource constraints to undermine essential defence capabilities (BBC, 2015b). It can be argued that the ‘can do’ approach that underpins mission-command and servant-leadership has allowed the military to lose its longer-term strategic focus when faced with current operational imperatives (Henry, 2011).

However, when faced with significant structural change, if appropriately applied the servant-leadership approach can provide the essential engagement needed to overcome the resistance to change that a business is likely to face (Kotter, 2010). When staff are given the opportunity to shape and take some ownership of the business transformation required, then changes are more likely to become embedded within the organisational culture and a shared appetite for continuous improvement can be developed (Lynch, 2009).

Servant-leadership approaches are more likely to result in the development and articulation of a shared vision, accepted by all staff and wider stakeholders (such as shareholders), particularly when people are given the flexibility to shape how they achieve their objectives in support of that vision (Linstead, Fulop & Lilley, 2009). The emergence of ‘change fatigue’ (where the perception of a constant crisis or series of crises undermines organisational confidence in the leadership) can also be mitigated as the engagement required allows staff to develop some ownership of the challenges being faced (Mullins & Christy, 2016). As a consequence, staff are likely to feel more empowered to anticipate emerging business situations, rather than simply react to them once corporate direction has been received (Johnson, Whittington, Scholes, Angwin & Regnér, 2014).

Since 2005, Greene King (the UK’s leading integrated pub retailer and brewer) has been led by Anand Rooney who has been credited with delivering increasing profitability and sustained expansion (CEO Dossier, 2015). It is argued that part of this success is due to Anand’s ability to move from the more directed and assigned leadership styles of his predecessor (i.e. relying on his hierarchical position) to a servant-leadership approach (Yukl, 2010). In doing so, he sought to engage the organisation in the development of his expansion vision, demonstrating that he understood the importance of balancing empowerment and understanding the tacit knowledge held by the people in his organisation (Johnson et al, 2016). Ultimately, he was able to change the corporate culture in order to gain engaged and committed followers rather than indifferent, disenfranchised subordinates (Zaccaro, 2007).

Ultimately, Anand built a shared corporate identity that reflected the culture and values of Greene King, ensuring that his vision was shared by the majority of people in the business (Mullins & Christy, 2016). In adopting a servant-leadership style, demonstrating greater flexibility and a willingness to support increased staff autonomy in how they met their objectives, Anand appears to have been able to create a critical point of competitive differentiation building a more responsive business model (Porter, 2004; CEO Dossier, 2015).

Leadership is essentially a process whereby the leader is able to influence others to achieve a common goal (Northouse, 2010). In order to successfully exert this influence, how the leader interacts with the people around them – often described as the styles and attributes of leadership – is often a critical factor (Yukl, 2010). Leadership is seen to be vested in the person (how their character and personality shape their effectiveness), embodied within processes (reflecting the culture and context being faced), built around position (organisational hierarchies) and achieving results (a successful leader gets things done) (Grint, 2005).

Whilst different models, theories and styles of leadership are stated to exist (Schedlitzki & Edwards, 2014), there is general consensus that it is built around the need to exercise power and manage power relationships (Mullins & Christy, 2016). This power can be built on information (the leader possessing knowledge others do not), reward and/or coercion (people depend on the leader), in legitimacy (their right to lead is recognised by others), expertise (seen as superior) or referent (the leader is a source of respect and admiration (Iszatt-White & Saunders, 2014). The effectiveness of a leader is further shaped by the organisational culture that exists and how they exercise power within that construct (Kakabadse, Ludlow & Vinnicombe, 1988).

The British Army’s approach to leadership is often cited as being distinctive and a model that should be emulated by more mainstream corporate entities (Yukl, 2010). The British Army’s leadership model is therefore examined in order to consider what potential lessons can be developed.[1]

Definition of Servant Leadership

“Servant leadership begins with the natural feeling that one wants to serve, to serve first. Then conscious choice brings one to aspire to lead…The difference manifests itself in the care taken by the servant – first to make sure that other people’s highest priority needs are being served’’ Greenleaf (1970)

The core academic texts appear to distinguish five key leadership styles[2]:

(Iszatt-White & Saunders, 2014; Yukl, 2010)

Alongside ethical leadership (doing the right things in the right way for the right reasons) and spiritual leadership (generating meaning, engagement and involvement, servant leadership – the ability to empower and direct others whilst giving clear direction and showing an element of humility – is regarded as a particular manifestation of the authentic leadership approach outlined (Manning & Curtis, 2009). However, the British Army have developed a different perspective, considering servant-leadership to be the core of any successful/enduring system of leadership that is able to quickly respond to changes in the operating environment (Joint Warfare Publication 0-10, 1999; Army Staff Officers Handbook, 1999)[3].

The Army’s approach is more of a cultural philosophy, rooted in the ethical responsibility of leaders, an innate almost spiritual understanding of people and values built around honesty, respect, trust and the development of talent (Mullins & Christy, 2016). The British military constantly strive to apply the hard-won lessons gained in conflict and – surprisingly for many external observers given the nature of the organisation – one of the most important observation has been the danger of relying on directive or autocratic leadership approaches (Latawski, 2011).

An over-prescriptive or leadership approach leads to military units being unable to respond quickly, efficiently and effectively to new threats, emerging tasks and fast-changing scenarios. The traditional (World War 1 and early World War 2) view of the strong, autocratic leader commanding from the centre of the battlefield actually creates a culture lacking in challenge, innovation and agility (Campbell, 1997). The British therefore seeks to adopt the ‘auftragstaktik’ (literally mission-tactics) approach learned from their early losses against the German Army in World War 2 (Campbell, 1997).

On the battlefield, emerging, (potentially favourable) situations will never be fully exploited if subordinate leaders have to seek new instructions or follow rigid, established procedures (Heifetz, Grashow & Linsky, 2009). Consequently, soldiers are encouraged to work in support of the mission rather than follow set orders, giving the freedom to adapt and exploit any evolving situation providing that they still carry out the mission concept outlined by their superiors (Matthews & Laurence, 2012).

Given the increasing complexity of the defence environment and significant resource constraints, subordinates must feel comfortable challenging the status quo without believing that they may risk their own position in the organisation (Yukl, 2010). The military therefore expend considerable effort in providing development interventions that provide soldiers with the knowledge, skills and support needed to strike an appropriate balance between following orders and exercising independent judgement (Price Waterhouse Change Integration Team, 1996; Joint Warfare Publication 0-10, 1999).

Servant-leadership as a military philosophy is therefore seen as essential if military forces are to remain cohesive and combat effective under such circumstances (army Staff Officers Handbook, 1999). It ensures that no gap between the leaders and the led can emerge – leaders remain visible, sharing the hardships and dangers faced by their staff when it is appropriate to do so (Latawski, 2011, Royal Military Academy Sandhurst, 2014).

Ultimately, servant-leadership provides one of the key determinants for military success – flexibility. This is seen as being a core principle of war-fighting and comprises agility, responsiveness, resilience, acuity and adaptability) (Latawski, 2011).[4]

Within the corporate business environment, leaders are increasing required to act as agents of change. They are expected to be strategic thinkers, but also demonstrate an ability to create a shared vision that drives success and create the culture required to maintain that success (Yukl, 2010). As this is founded in the need to respond to a rapidly changing operating environment, then adopting/adapting the British Army’s approach to leadership could deliver an enduring competitive advantage (Porter, 2004).

However, the British Army has been criticised for its continuing inability to adapt to the cultural and social changes present within the community from which it recruits, leading to significant capability shortfalls (BBC, 2015a: Farmer, 2017). The leadership have also been challenged for being too flexible and responsive when faced with Government demands, allowing imposed resource constraints to undermine essential defence capabilities (BBC, 2015b). It can be argued that the ‘can do’ approach that underpins mission-command and servant-leadership has allowed the military to lose its longer-term strategic focus when faced with current operational imperatives (Henry, 2011).

However, when faced with significant structural change, if appropriately applied the servant-leadership approach can provide the essential engagement needed to overcome the resistance to change that a business is likely to face (Kotter, 2010). When staff are given the opportunity to shape and take some ownership of the business transformation required, then changes are more likely to become embedded within the organisational culture and a shared appetite for continuous improvement can be developed (Lynch, 2009).[6]

Servant-leadership approaches are more likely to result in the development and articulation of a shared vision, accepted by all staff and wider stakeholders (such as shareholders), particularly when people are given the flexibility to shape how they achieve their objectives in support of that vision (Linstead, Fulop & Lilley, 2009). The emergence of ‘change fatigue’ (where the perception of a constant crisis or series of crises undermines organisational confidence in the leadership) can also be mitigated as the engagement required allows staff to develop some ownership of the challenges being faced (Mullins & Christy, 2016). As a consequence, staff are likely to feel more empowered to anticipate emerging business situations, rather than simply react to them once corporate direction has been received (Johnson, Whittington, Scholes, Angwin & Regnér, 2014).[7]

Since 2005, Greene King (the UK’s leading integrated pub retailer and brewer) has been led by Anand Rooney who has been credited with delivering increasing profitability and sustained expansion (CEO Dossier, 2015). It is argued that part of this success is due to Anand’s ability to move from the more directed and assigned leadership styles of his predecessor (i.e. relying on his hierarchical position) to a servant-leadership approach (Yukl, 2010). In doing so, he sought to engage the organisation in the development of his expansion vision, demonstrating that he understood the importance of balancing empowerment and understanding the tacit knowledge held by the people in his organisation (Johnson et al, 2016). Ultimately, he was able to change the corporate culture in order to gain engaged and committed followers rather than indifferent, disenfranchised subordinates (Zaccaro, 2007).

Ultimately, Anand built a shared corporate identity that reflected the culture and values of Greene King, ensuring that his vision was shared by the majority of people in the business (Mullins & Christy, 2016). In adopting a servant-leadership style, demonstrating greater flexibility and a willingness to support increased staff autonomy in how they met their objectives, Anand appears to have been able to create a critical point of competitive differentiation building a more responsive business model (Porter, 2004; CEO Dossier, 2015).[8]

In developing the arguments and analysis outlined within the case study – particularly if seeking to challenge the assertions made – the following further reading is recommended:

Army Staff Officers Handbook. (1999). Army Code Number 71038, London: The Stationery Office.

BBC. (2015a). Army needs more minority recruits – Gen Sir Nick Carter. [Online], Available: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-31158062 [22 March, 2017].

BBC. (2015b). Can the UK afford to defend itself? [Online], Available:

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-31692143 [22 March, 2017].

Bryman, A., Bell, E. (2015). Business Research Methods, 4th Edition, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Campbell, A. (1997). A British General Staff – Imperial Throwback or Strategic Imperative?, Royal United Services Institute Journal 97(8), pp51-56.

CEO Dossier. (2015). Rooney Anand [Online], Available: http://www.worldofceos.com/dossiers/rooney-anand [21 March, 2017].

Cottrell, S. (2011). Critical Thinking Skills: Developing Effective Analysis and Argument, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Farmer, B. (2017). Army fights troops shortfall with new recruitment ads about camararderie. [Online], Available: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/01/06/army-fights-troops-shortfall-new-recruitment-ads-camaraderie/ [22 March, 2017].

Fisher, A. (2001). Critical Thinking: An Introduction, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gotsis, G., Grimani, K. (2016). The role of servant leadership in fostering inclusive organizations, Journal of Management Development, 35(8), pp. 985-1010.

Grint, K. (2005). Leadership: Limits and Possibilities, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hanscomb, S. (2017). Critical Thinking: the basics, Abingdon: Routledge

Heifetz, R., Grashow, A., Linsky, M. (2009). The Practice of Adaptive Leadership: Tools and Tactics for Changing your Organization and the World, Boston: Harvard Business Press.

Henry, A.E. (2011). Understanding Strategic Management, 2nd Edition, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Johnson, G., Whittington, R., Scholes, K., Angwin, D., Regnér, P. (2014). Exploring Strategy: Text and Cases, 10th Edition. Harlow: Pearson Education Ltd.

Joint Warfare Publication 0-10. (1999). United Kingdom Doctrine for Joint and Multinational Operations, London: The Stationary Office.

Iszatt-White, M., Saunders, C. (2014). Leadership, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kakabadse, A., Ludlow R., Vinnicombe, S. (1988). Working in Organisations, Aldershot: Penguin.

Kotter, J.P. (2010). Leading Change: Why Transformation Efforts Fail, Boston: Harvard Business Review Press.

Latawski, P. (2011). Sandhurst Occasional Papers No.5: The Inherent Tensions in Military Doctrine. [Online], Available: http://www.army.mod.uk/documents/general/RMAS_Occasional_Paper_5.pdf [21 March, 2017].

Linstead, S., Fulop, L., Lilley, S. (2009). Management & Organization: A Critical Text, 2nd Edition, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Lynch, R. (2009). Corporate Strategy, 5th Edition, Harlow: Pearson Education Ltd.

Manning, G., Curtis, K. (2009). The Art of Leadership, 3rd Edition, New York: McGraw-Hill Companies Inc.

Matthews, M.D., Laurence, J.H. (2012). The Oxford Handbook of Military Psychology, New York: Oxford University Press.

Mullins, L.J., Christy, G. (2016). Management & Organisational Behaviour, 11th Edition, Harlow: Pearson Education Ltd.

Norris, S., Ennis, R. (1989). Evaluating Critical Thinking, Pacific Grove (CA): Critical Thinking Press and Software.

Open University. (2016). Critical Thinking Stairway. [Online], Available: https://learn1.open.ac.uk/mod/oublog/viewpost.php?post=178090 [21 March, 2017].

Porter, M.E. (2004). Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance, New York: Free Press Inc.

Price Waterhouse Change Integration Team. (1996). The Paradox Principles: How High-Performing Companies Manage Chaos, Complexity and Contradiction to Achieve Superior Results, Chicago: Irwin Professional Publishing.

Royal Military Academy Sandhurst (2017) [Online], Available: http://www.army.mod.uk/training_education/24475.aspx [21 March, 2017].

Schedlitzki D., Edwards, G. (2014). Studying Leadership: Traditional and Critical Approaches, London: Sage Publications Ltd

Stone, G.A., Russell, R.F., Patterson, K. (2004). Transformational versus servant leadership: a difference in leader focus, Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 25(4), pp. 349-361.

Thomson, A. (2009). Critical Reasoning: a practical introduction, 3rd Edition, Abingdon: Routledge

Williams, K. (2014). Getting Critical: Critical Evaluation, 2nd Edition, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Winston, B., Fields, D. (2015) Seeking and measuring the essential behaviors of servant leadership, Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 36(4), pp. 413-434.

Yukl, G. (2010). Leadership in Organizations, 7th Edition, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Zaccaro, S.J. (2007). Trait-based perspectives of leadership, American Psychologist, 62(1), pp. 6-16.

[1] These opening paragraphs set the context and bound the argument to be presented based on what is ‘read, seen, heard or done’ – the initial process step of the Open University ‘stairway’ model

[2] The following section creates the basis for understanding – placing the subsequent discussion of servant-leadership in a recognised and accepted academic context.

[3] In developing essential understanding, referencing that provides appropriate context is essential. The military publications cited are therefore important elements and support the critical thinking required. Where the situation or context is likely to be unfamiliar to the target audience, then it is appropriate to spend longer developing this aspect in order to ensure that any subsequent analysis and synthesis is understood. This has been the approach taken in this case study.

[4] This examination of the Army’s leadership approach/philosophy takes the academic model and provides essential context and argument as to why it is seen to be effective. This outline analysis provides the foundation for subsequent critical evaluation.

[5] The proposition must now be carefully examined in order to consider its wider relevance. Model comparisons are made, an analytical synthesis is proposed which can then be reviewed and evaluated.

[6] Synthesising/Evaluating Kotter’s Change model and relating it to the concept of servant-leadership as a critical change enabler.

[7] Here, the military’s approach to servant-leadership is applied in a different context – both as part of a change process and within a (civilian) corporate setting.

[8] Extrapolating the arguments presented provides the required justification i.e. the implication/suggestion that adopting a (military) leadership style in a commercial context could deliver an enduring competitive advantage. In a longer case study, it would be essential to challenge this assertion.

You have to be 100% sure of the quality of your product to give a money-back guarantee. This describes us perfectly. Make sure that this guarantee is totally transparent.

Read moreEach paper is composed from scratch, according to your instructions. It is then checked by our plagiarism-detection software. There is no gap where plagiarism could squeeze in.

Read moreThanks to our free revisions, there is no way for you to be unsatisfied. We will work on your paper until you are completely happy with the result.

Read moreYour email is safe, as we store it according to international data protection rules. Your bank details are secure, as we use only reliable payment systems.

Read moreBy sending us your money, you buy the service we provide. Check out our terms and conditions if you prefer business talks to be laid out in official language.

Read more