A Critical Review of “Chickens prefer beautiful humans” by Ghirlanda,Jansson, & Enquist (2002)

Introduction and summary of the reviewed paper

Ghirlanda, Jansson, & Enquist (2002) conducted an experiment on chicken’s preferences for human faces and compared such preferences to humans’ facial preferences in attempt to explain the origin of humans’ sexual preferences for faces. In this study, six chickens (two males and four females) were trained to response to an average human face with opposite sex to them (indicated with an arrow in Figure 1), which were created by averaging 35 different human face images of each sex (Ghirlanda et al., 2002). The trained chickens were then tested with a whole set of seven faces (Figure 1), which consisted of the two average male and female faces, an average face of the two averages and two faces with enhanced sexual traits of each sex (Ghirlanda et al., 2002). The number of pecks of the chickens to each face was recorded (Ghirlanda et al., 2002). Further, 14 human subjects were required to rate the seven faces on a scale from 0 to 10 in respect of the extent that they would like to date with that ‘person’ (Ghirlanda et al., 2002).

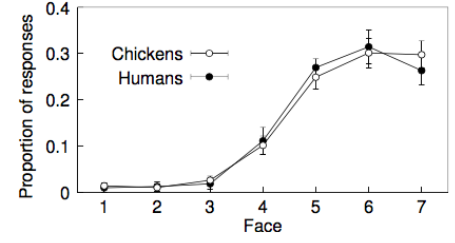

The relative scores of each face given by human subjects were compared with the proportion of pecks of chicken subjects to each face (Ghirlanda et al., 2002). Figure 2 shows that the facial preferences of both the human and chicken subjects are remarkably similar and this result is statistically significant (Ghirlanda et al., 2002). Based on the above findings, Ghirlanda et al. (2002) concluded that similar results of facial preferences can be found in any nervous system,chickens’ in this case,if appropriate trainings of reacting with human faces are provided,which indicates that facial preferences are justby-products of general information processing mechanismsand are not adaptation to mate choice.

In this review, the above study by Ghirlanda et al. (2002) will be critically analysed in respect of two main possible issues: are facial preferences just by-products of general information processing mechanisms instead of adaptations to mate choice? And does comparing chickens’ perception of human face images with that of humans have any validity? In addition, an implication for further research on human recognition ability will be suggested.

Figure 1 A set of face images presented in Ghirlanda et al. (2002)

Figure 2 Results of Ghirlanda et al. (2002)

Are facial preferences just by-products of general information processing mechanisms instead of adaptations to mate choice?

According to Thornhill & Gangestad (1999), the mate quality hypothesis suggests that facial preferences are adaptation to sexual selection as facial traits are indicators of an individual’s quality. For instance, attractive faces are associated with health (Zebrowitz & Rhodes, 2004). Zebrowitz & Rhodes (2004) reanalysed the data of a study on the relation between facial attractiveness and infectious diseases by Kalick, Zebrowitz, Langlois, & Johnson (1998). Kalick et al. (1998) collected data of the severity and frequency of some infectious diseases and the facial attractiveness of a large sample size. It is notable that the samples were individual that were born in the 1920s as this indicated that the relation between facial attractiveness and infectious diseases would be less likely to be affected by the use of vaccinations and antibiotics (Kalick et al., 1998). Results showed that there was a moderate effect of facial attractiveness at 17 on later health (Zebrowitz & Rhodes, 2004). Although evidences support that facial attractiveness correlates with health, health is just one of the factors that determine the quality of an individual. Little evidence indicates links between facial attractiveness and other components of quality such as fertility and intelligence (Rhodes, 2006).

However, Rubenstein, Kalakanis, & Langlois (1999) conducted four studies on six-month-old infants’ facial preferences, which suggested that facial preferences are just by-products of general information processing mechanisms. In the first two studies, face images of 32 young adult females and an averaged face image of these 32 faces were presented to both groups of participants, adults and infants, separately (Rubenstein et al., 1999). The adults’ rating and the infants’ time spent looking at each face were recorded (Rubenstein et al., 1999). Results indicated that both the adult and infant subjects showed preferences for the averaged face (Rubenstein et al., 1999). In the other two studies, infants were presented with eight face images of similar level of attractiveness, rated by adults (Rubenstein et al., 1999). After familiarising with those face images, different face images, including the eight familiar faces, an averaged face of the familiar faces and some novel faces, were shown to the infants (Rubenstein et al., 1999). Infants spend significantly more time looking at the novel faces than both the familiar and averaged faces, while no significant difference was found between the infants’ time spent looking at the familiar and averaged faces (Rubenstein et al., 1999). By concluding the results of all these studies, it was suggested that infants have the cognitive ability to average a large set of faces in a short period of time, which then contributes to their development of facial preferences (Rubenstein et al., 1999). In addition, Quinn, Kelly, Lee, Pascalis, & Slater, (2008) conducted several experiments on the preferences for attractive faces of another species and the results showed supporting evidences the above study (Rubenstein et al., 1999) that the emergence of facial preferences is due to general information processing mechanisms. During the experiments, four-month-old human infants were provided with both attractive and unattractive cat face pictures, rated by adults, and the time spent looking at each picture was recorded (Quinn et al., 2008). It was found that infants spent significantly more time looking at the attractive cat face pictures than the unattractive ones, indicating a preference for cat faces (Quinn et al., 2008). As this result suggests that facial preference in infants is not human-specific and preferences for attractive cat faces are not related to mate choice, it supports that facial preferences are in fact by-products of general information processing mechanisms (Quinn et al., 2008).

From the analysis of above literatures (Rubenstein et al., 1999; Quinn et al., 2008), the claim by Ghirlanda et al. (2002) that chickens have facial preferences for attractive human faces just like humans do implies that such preferences are not species-specific and therefore support that facial preferences are not specific adaptations to mate choice but instead, they are activities of general information processing mechanisms. Zebrowitz & Rhodes (2004) argued that preferences for attractive faces are adaptation to mate choice as facial trait indicates individuals’ quality, however, there is little evidence to support this claim. Therefore, it can be concluded that the conclusion of Ghirlanda et al. (2002) is logical and well supported.

Does comparing chickens’ perception of human face images with that of humans have any validity?

In order to examine chickens’ ability to recognise human faces, an experiment using controlled rearing method was carried out in the study by Wood & Wood (2015). 13 chicks were reared in experimental conditions with no exposure to light for their first week of life and a video with a human face was shown to the chicks using a projector (Wood & Wood, 2015). On the second week, the human face of that video and another unfamiliar human face were presented to the chicks at the same time (Wood & Wood, 2015). Results showed that chicks spent significantly more time staying near the familiar face than the unfamiliar one, which indicates that chicks could accurately discriminate different human faces (Wood & Wood, 2015). Additionally, a study by Stephan, Wilkinson, & Huber (2012) suggested that not only chicken, pigeons also have the ability to discriminate human faces. Eight pigeon were tested with a discrimination task by providing photos of some familiar and unfamiliar faces (Stephan et al., 2012). The pigeons peck significantly more at the photos of familiar faces than the unfamiliar ones (Stephan et al., 2012). The above results are in line with findings of a biological study of birds by Karten (2013), which suggested that the visual systems of both humans and birds in terms of forming facial images are similar. Despite the fact that the brain structures of humans and birds are significantly different from each other, they are almost the same in the aspect of neural circuits for processing sensory information (Karten, 2013).

The results of Ghirlanda et al. (2002) were produced by comparing chickens’ perception of human face images with that of humans. However, chickens and humans have different brain structures, making it questionable to use such methodology to produce the results. Nevertheless, the above research (Wood & Wood, 2015; Stephan et al., 2012; Karten, 2013) provided strong evidence that birds, especially chickens, could distinguish between different human faces and form face images in similar ways as humans. Therefore, the methodology used by Ghirlanda et al. (2002) in producing its results had high validity.

Implications for further research

As mentioned above, the methodology of comparing humans with chicken in the aspect of recognition ability has high validity and thus further research on topics related to humans’ recognition ability or visual system can adopt a modified version of the above method. There are several advantages of using chickens as study subjects (Wood & Wood, 2015). First of all, as previously mentioned, humans and chickens have almost identical information processing mechanisms and chickens have similar visual recognition ability as humans (Karten, 2013). Second, chickens are suitable for living in experimental conditions as they have fewer needs for parental care and are highly adaptive to environment without any objects (Wood & Wood, 2015). Third, chickens, especially chicks, can form bonds with any objects easily without any training, which may reduce time costs of an experiment (Horn, 2004). These attributes make chickens a decent animal subject for the purpose of studying human visual recognition. This may be applied to study on inability of face recognition in humans, such as prosopagnosia (Barton, Press, Keenan, & O’Connor, 2002).

Conclusion

In this critical review of the study by Ghirlanda et al. (2002), the original conclusion that facial preferences are just the activities of general information processing mechanisms and the validity of its methodology of comparing chickens’ perception of human face images with that of humans were criticised. Several research (Rubenstein et al., 1999; Quinn et al., 2008; Wood & Wood, 2015; Stephan et al., 2012; Karten, 2013) have shown supporting evidences, as mentioned above, to the claims of the original paper, which suggests that both the conclusion and the methodology of the reviewed paper have high validity. Based on the ideas of the reviewed study, an implication suggesting that further research on human recognition ability can choose chicken as an animal subject for obtaining reliable results has been developed. Despite the fact that this review has some limitations, as it does not include a wide variety of studies, for instance, neuroimaging studies, overall I believe this to be a logical analysis.

References

Barton, J., Press, D., Keenan, J., & O’Connor, M. (2002). Lesions of the fusiform face area impair perception of facial configuration in prosopagnosia. Neurology, 58(1), 71-78.

Ghirlanda, S., Jansson, L., & Enquist, M. (2002). Chickens prefer beautiful humans. Human Nature, 13(3), 383-389.

Horn, G. (2004). Pathways of the past: the imprint of memory. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 5(2), 108-120.

Kalick, S., Zebrowitz, L., Langlois, J., & Johnson, R. (1998). Does Human Facial Attractiveness Honestly Advertise Health? Longitudinal Data on an Evolutionary Question. Psychological Science, 9(1), 8-13.

Karten, H. (2013). Neocortical Evolution: Neuronal Circuits Arise Independently of Lamination. Current Biology, 23(1), R12-R15.

Quinn, P., Kelly, D., Lee, K., Pascalis, O., & Slater, A. (2008). Preference for attractive faces in human infants extends beyond conspecifics. Developmental Science, 11(1), 76-83.

Rhodes, G. (2006). The Evolutionary Psychology of Facial Beauty. Annual Review Of Psychology, 57(1), 199-226.

Rubenstein, A., Kalakanis, L., & Langlois, J. (1999). Infant preferences for attractive faces: A cognitive explanation. Developmental Psychology, 35(3), 848-855.

Stephan, C., Wilkinson, A., & Huber, L. (2012). Have we met before? Pigeons recognise familiar human faces. Avian Biology Research, 5(2), 75-80.

Thornhill, R. & Gangestad, SW. (1999). Facial attractiveness. Trends Cogn Sci., 3(12), 452-460.

Wood, S. & Wood, J. (2015). Face recognition in newly hatched chicks at the onset of vision. Journal Of Experimental Psychology: Animal Learning And Cognition, 41(2), 206-215.

Zebrowitz, L. & Rhodes, G. (2004). Sensitivity to “Bad Genes” and the Anomalous Face Overgeneralization Effect: Cue Validity, Cue Utilization, and Accuracy in Judging Intelligence and Health. Journal Of Nonverbal Behavior, 28(3), 167-185.

You have to be 100% sure of the quality of your product to give a money-back guarantee. This describes us perfectly. Make sure that this guarantee is totally transparent.

Read moreEach paper is composed from scratch, according to your instructions. It is then checked by our plagiarism-detection software. There is no gap where plagiarism could squeeze in.

Read moreThanks to our free revisions, there is no way for you to be unsatisfied. We will work on your paper until you are completely happy with the result.

Read moreYour email is safe, as we store it according to international data protection rules. Your bank details are secure, as we use only reliable payment systems.

Read moreBy sending us your money, you buy the service we provide. Check out our terms and conditions if you prefer business talks to be laid out in official language.

Read more