|

Table 1 |

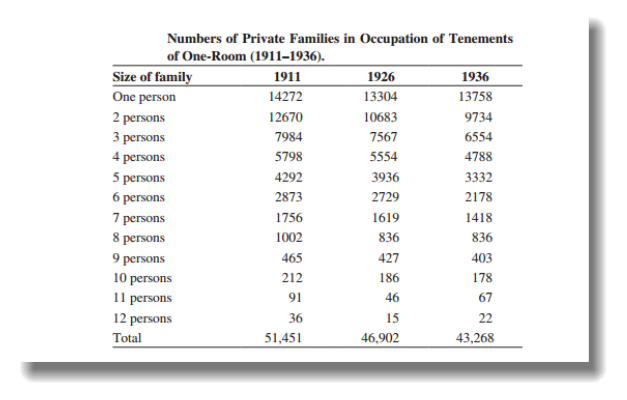

Number of Private Families in Occupation of Tenements of One-Room (1911-1936) |

|

Table 2 |

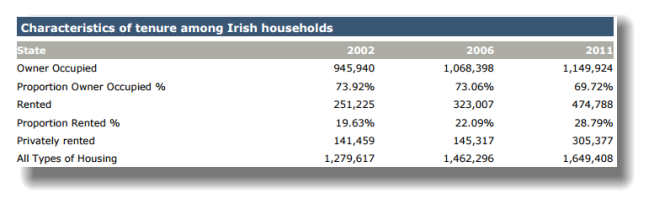

Characteristics of Tenure among Irish Households |

|

Table 3 |

List of The top 10 AHBs by size |

|

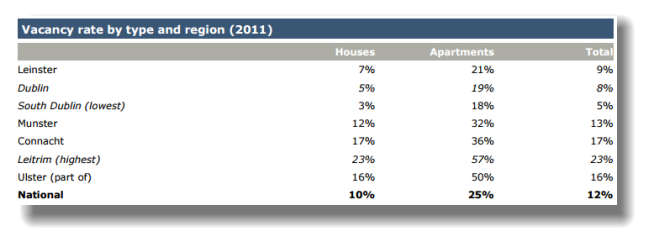

Table 4 |

Vacancy rate by type and region in 2011 |

|

Table 5 |

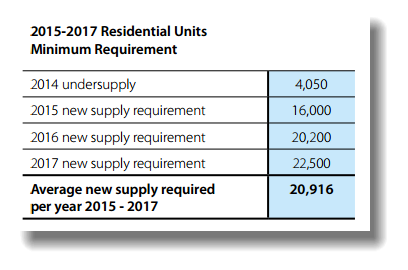

2015-2017 Residential units minimum requirement |

|

Table 6 |

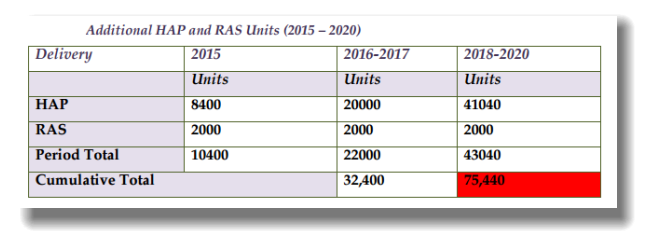

Additional HAP and RAS Units (2015-2020) |

|

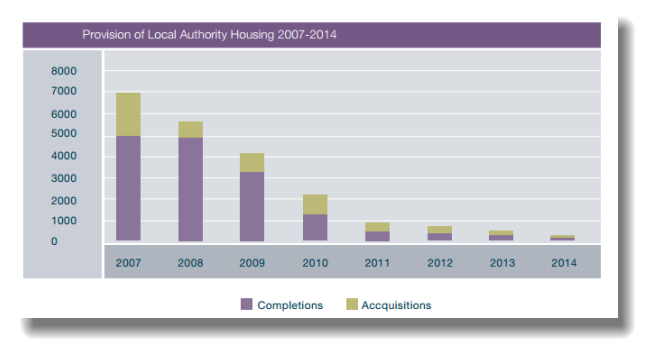

Figure 1 |

Provision of Local Authority Housing 2007-2014 |

|

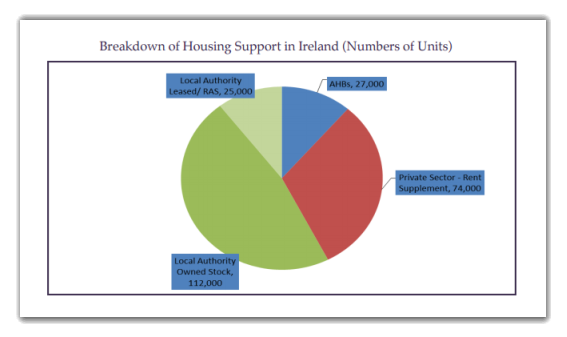

Figure 2 |

Breakdown of Social Housing Support in Ireland (Number of Units) |

|

Figure 3 |

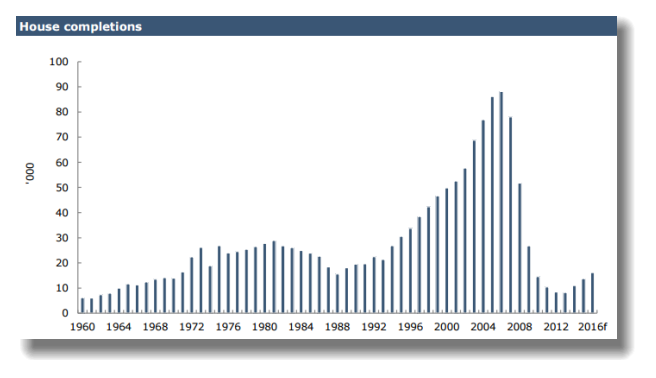

House completions |

|

RAS |

Rental Accommodation scheme |

|

HAP |

Housing Assistance Payment |

|

AHBs |

Approved Housing Bodies |

|

CAS |

Capital Assistance Scheme |

|

PAA |

Payment and Availability Agreement |

|

CALF |

The Capital Advanced Lending Facility |

|

NESDO |

National Economic & Social Development office |

‘The development of the Irish housing system from the iconic period of the 1840s to the 1970s, when a new era of development began in Ireland, laid the foundations for the system today.’ (CHAPTER 2. 2011, p.54).

This literature review outlines the evolution of social housing in Ireland from the beginning to the present day. It comprises of seven parts. Part 1 provides a brief history of tenements in Dublin; Slum clearance and Dublin’s corporation housing schemes; ownership. Part 2 examines the Social housing providers in Ireland. Part 3 Funding for social housing. Part 5 analyzes Social housing Supply and Demand; Part 6 is about Social Housing Need; Part 7 describes what the sources of social housing supply in Ireland are.

‘The origin of tenements in Dublin may be tracked back as far as the sixteenth century when the population probably did not exceed sixty thousand.'(Kearns, K.C.2006)

The vast majority of the Irish population lived in rural areas. Great famine and industrialization in urban areas had led to a growth in slum housing due to increased population, as well as poor sanitation and the spread of disease. (Chapter 2. 2011).

Between 1841 and 1900 Ireland’s population declined but Dublin’s increased from 236,000 to 290,000. Dublin’s slums were the worst in all of Europe for nearly 150 years. Between 1900 and 1938 there were over six thousand tenement houses in Dublin occupied by over one hundred thousand tenement dwellers. Those people had occupied spacious Georgian houses abandoned by their original owners who left into newly-built suburbs. House prices dropped and went into the hands of landlords who tried to fit houses with as many residents as they could. Dwellings that had once been single-family homes were increasingly divided into multiple living spaces to accommodate this growing population. It was a logical solution for the city’s lower classes who were simply seeking space to sleep in and shelter. (Kearns, K.C.2006).

Tenement dwellings were overcrowded, some areas had 800 people to the acre. In one house lived as many as a hundred persons. Accordingly, in a single tiny room lived fifteen to twenty family members. (Kearns, Kevin C.2006).Table 1 demonstrates how many people lived in a one room tenements. (Census of Population. 1936). Despite the fact that Dublin’s overall density was 38.5 persons per acre the density statistics were astonishingly high as for example: Inns Quay 103, Rotunda 113, Mountjoy 127, and Wood Quay 138. Massive population was concentrated in close-knit communities around the Liberties, dockland and Northside.

Table 1Source: Census of Population 1936

The living conditions were hellish. The buildings were not properly maintained and therefore were decayed, dangerous, and sometimes collapsed, killing occupants. The greatest deterioration and decay that buildings suffered was the second half of the nineteenth century. Those tenement districts were known as slumlands. (Kearns, K.C.2006).

‘The slums along Church Street, Beresford Street, Cumberland Street, Railway Street, Gardiner Street, and Corporation Street and on Mary’s Lane were particularly appalling. The worst tenement slums around Liberties were on the Coombe and Francis Street, Cork Street, Chamber Street, and Kevin Street.’ (Kearns, K.C.2006, p.8).

Maintenance and repair of the buildings was very expensive, so only the remaining wealthy Georgian house residents were able to do so because residents had no financial resources to keep buildings in a prime form. As a result over 60,000 people were in need of re-housing. There was a critical housing shortage.

Dublin’s slums existed until 1940s. (Kearns, K.C.2006)

The first nationwide system of welfare was formed on The Poor Relief (Ireland) Act 1838. Unfortunately system was not able to manage such huge levels of poverty and homelessness. (Meghen. 1955, p.44)

In the end of 19th century there were a lot of various schemes, and legislation acts such as Public Health Act 1848, Artisans and Laborer’s Dwellings Act 1875, Housing of the Working Classes Act 1890, etc.; Charitable trusts, Philanthropic trusts, Guinness Trust, Sutton Housing Trust and many others that had to provide affordable and good quality social housing and also housing for the working classes. (Chapter 2. 2011, p.21-25).

Despite all efforts the housing shortages were growing and by the 1914 tenement housing situation was so desperate that a real solution was needed without delay. (Kearns, K.C.2006).

First intentions to promote slum clearance was not successful due to high cost of slum sites and re-housing of households. (Chapter 2. 2011).

‘Only with the creation of the 1913 Housing Bill and the 1932 Housing Act did attention focus on financing slum clearance schemes and the provision of local authority housing for the lower-income classes. For the first time local authorities were empowered to deal directly with the slum problem in a systematic way. Unfit properties could be officially condemned and acquired compulsorily to be renovated or demolished.’ (Kearns, K.C.2006, p.21).

During the 1940s and 1950s the Corporation has set a target that was a part of slum clearance program, to build four and five-story blocks of flats across the city center. Also at the same time, new housing development projects have been implemented in Cabra, Ballyfermot, Crumlin, Glasnevin, Donnycarney and Marino. (Kearns, K.C.2006, p.21).

According to the Kenny’s Report (1973) the Irish population had increased from 1,229,000 in 1961 to 1,556,000 in 1971. Migration and economic growth increased need for housing and White Paper (1969) estimated that 15-17,000 houses would be required by the mid-1970s annually.

In the nearly 20th century only 20% of all Irish population were the owners of their houses and the rest 90% have rented their accommodation. (Sirr L. 2014).

‘Home ownership quelled agitation for three reasons: having improved living conditions removed a primary cause of protest and discontent; a regular income was needed in order to maintain the newly owned home in respectable manner, which implied the requirement to be in work; and home owners were less likely to strike or protest due to fact that they now had something to lose-their homes.’ (Sirr L. 2014. p3).

There was a various sales and taxation schemes that encouraged and facilitated Home ownership. (Sirr L. 2014). Over the number of years Ireland become as a nation of home owners. (Goodbody. 2015, p.15).

However ‘there are new generation of renters, not forced, but wanting to rent for personal and professional reasons, and the private rented sector is now replete with people who choose to rent, not because they couldn’t get a mortgage but because they do not want to own a property.’ (Sirr L. 2014. p6).

The table 2 below shows the number of renters increased during decade. Goodbody states that in 2011, there were 29% of households rent, with 18.5% of those in the private sector. (2015)

Table 2Source: Goodbody 2015

More people are now renting, while people on lowest incomes are squeezed out of the relatively small rental market and are at greater risk of homelessness. (Irish Times, 8 Oct, 2015)

In 2011 the National Economic and Social Council stated that the main future providers of new social housing will be the housing associations. (2014). There are three main providers of social housing accommodation in Ireland:

Local authorities are the largest providers of social housing that dominate for nearly 120 years and controlled approximately 137,000 dwellings in 2014. The provision of social housing units by local authorities which is evident from Figure 1.

Figure 1Source: Department of the Environment, Community and Local Government

Approved Housing Bodies (AHBs). There are some 500 in Ireland that manage approximately 27,000 homes. Until 2011 AHBs were 100% funded by government under Capital Assistance Scheme (CAS). The top 10 are listed by size in the table 3 below.

Table 3Source: Housing Agency, 2014

Private rental sector provides accommodation for 74,000 households supported by Rent Supplement.

(Environment, Community and Local Government. 2014).

The breakdown of housing support in Ireland is demonstrated in a Figure 2.

Figure 2Source: The Social Housing Strategy 2020

According to Social housing newsletter published in 2012 there are the main grant funding schemes in Ireland:

Local authority acquisition/construction program. By this programme local authorities buy or construct new housing units. Government provides 100% capital grant.

Capital Assistance Scheme (CAS). Operates since 1984. Funding up to 100%. Scheme is for AHBs that provide housing for people with specific needs i.e. elderly, homeless people, and people with disabilities.

Payment and Availability Agreement (PAA). This programme is designed to assist Approved Housing Bodies that make their properties available for use as social housing for around 30 years.

Capital Advance Leasing Facility (CALF) Provides a long-term government loan for a 25 year period with a simple fixed interest rate of 2% per annum. Established in 2011.

The Housing Finance Agency Provides loan to local authorities and AHBs social housing and other housing-related purposes. Established in 1982.

Commercial lenders. Some interest in lending to the sector with a maximum duration of 7-10 years have shown Bank of Ireland, Allied Irish Bank and Ulster Bank.

(Fund Structuring Services Final Report, 2014)

The Social Housing Leasing Initiative Launched in 2009. Properties are leased from private property owners. The purpose is to provide accommodation to those on social housing waiting lists.

The Capital Advanced Lending Facility (CALF). This is along-term government loan, when 30 per cent of the total funding required is covered by government, and balance is covered from a financial institution. Introduced in 2011 and is for term of between 10 and 30 years.

Demand for housing will continue to increase. According to new figures from the Housing Agency homes that were built in Dublin last year only met half of the demand’. Ireland’s population increased by 30% in the last 20 years. At the moment approximately 4.6 million people live in a country. It is the highest population for 150 years. An increasing population and a declining household size will both increase demand for housing units. (2015).

National Economic & Social Development office (NESDO) defines the factors that stimulate housing demand:

According to Goodbody’s research, to meet demand the housing supply needs to increase. (2015)

The Irish housing market experienced an oversupply due to an overbuilding in the 2000s boom years. As a result 11.5% of the housing stock was vacant in 2011. But at the same time there was significant supply shortages in Dublin standing at 5%. (Goodbody. 2015). Table 4 demonstrates vacancy rate by type and region in 2011.

Table 4Source: Goodbody 2015

Table 4Source: Goodbody 2015

In recent years demand for social housing has been rising due to increased population. Table 5 below outlines that almost 21,000 additional residential units are required to be supplied each year over the next three years to meet demand.

Table 5Source: Housing Agency. Outlook for 2015-17

Factors that may affect the slow supply:

There are now 100,000 people on the social housing waiting list. Government announced recently that it will supply 35,000 additional housing units over the next six years as part of its Social Housing Strategy. In 2014 Irish housing completions grew by 33% to 11,000 units (Goodbody. 2015) as the figure 3 shows below:

Figure 3Source: Goodbody 2015

‘The Irish housing market has changed radically in recent years and the existing framework underpinning the supply and funding of social housing supports is no longer adequate to address housing need.'(Coffey, 2004).

The Environment, Community and Local Government (2014) excludes six main groups in the Housing Needs Assessment:

‘It is estimated that c.40% of households in the private rental sector are in receipt of some form of government support.’ (Goodbody. 2015, p.16).

Rent Supplement was started in 1970s as a short-term housing or welfare support. (Sirr L. 2014, p.79). It ‘has played a central role in the expansion of the private rented sector”p31 and has become increasingly important for low-income tenants.’ (Sirr L. 2014, p.31). Rent Supplement is paid to people who are jobless and whose main income comes from social welfare payments. In other words it is payable for those who cannot provide accommodation from their own resources. People who are in full-time employment cannot claim Rent Supplement. (Sirr L. 2014, p.80)

Rental Accommodation Scheme (RAS) was established in 2004 for those who were getting Rent Supplement for long time (eighteen months or longer). ‘If Social housing was not available, they were accommodated in a private rented dwellings which were leased by local government for four to ten years.’ (Sirr L. 2014p31). Contracts were drawn up between Local authorities and Landlords to provide housing for people with a long-term housing need. Rent is between 88 and 92 per cent of the market rent and is paid directly to the landlord. (Citizens information, 2012).

Housing Assistance Payment (HAP) is a new social housing support that replaced Rent Supplement introduced in 2014. Rent is directly paid to the Landlord by Local authority. (Citizens information, 2015).

Table 6 outlines the number of households that are expected to be accommodated directly under HAP and RAS during 2015-2020.

Table 6Source: Environment, Community and Local Government (2014)

Social Housing Strategy 2020

Minister for the Environment, Community and Local Government Alan Kelly said that ‘Working together, and through combining public, voluntary and private investment, we can provide our growing population with the required level of quality, affordable homes.’ (2014)

‘The strategy responds robustly to that challenge by providing a roadmap that will accommodate 90,000 households, the entire Housing Waiting List, by 2020.’ (Coffey, 2004). It has a new vision to provide an access to secure, good quality and affordable housing every household in Ireland. Over a period of six years should be provided 35,000 new social housing units, also 75,000 households should be supported through the private rental sector. (Environment, Community and Local Government. “The Social Housing Strategy 2020: Support, Supply and Report”. 2014).

Environment, Community and Local Government states that their plans should be delivered during two phases: ‘Phase 1, building on Budget 2015, sets a target of 18,000 additional housing units and 32,000 HAP/RAS units by end 2017. Phase 2 sets a target of 17,000 additional housing units and 43,000 HAP/RAS units by end 2020.'(2014).

Census of Population, (1936), [Online]. Available: http://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/census/census1936results/volume1/C,1936,Vol,1.pdf [Accessed 6th October 2015].

Chapter 2, (2011) Outline of the Development of the Irish Housing System [Online]. Available: http://www.nuigalway.ie/media/housinglawrightsandpolicy/Chapter-2-Outline-of-the-Development-of-the-Irish-Housing-System-Housing-Law,-Rights-and-Policy.pdf [Accessed 6th October 2015].

Citizens’ information (2012) Rental Accommodation Scheme [Online]. Available: http://www.citizensinformation.ie/en/housing/local_authority_and_social_housing/rental_accommodation_scheme.html [Accessed 7th October 2015].

Coffey, P TD Minister of State Department of the Environment, Community and Local Government (2014). In Environment, Community and Local Government. The Social Housing Strategy 2020: Support, Supply and Report. [Online]. Available: http://www.environ.ie/en/PublicationsDocuments/FileDownLoad,39622,en.pdf [Accessed 30th September].

Environment, Community and Local Government (2014). The Social Housing Strategy 2020: Support, Supply and Report. [Online]. Available: http://www.environ.ie/en/PublicationsDocuments/FileDownLoad,39622,en.pdf [Accessed 30th September].

European Investment Bank (2014) Final Report for the Department of Public Expenditure and Reform: Social Housing and Energy Efficiency in Ireland. Fund Structuring Services. [Online] Available: http://per.gov.ie/wp-content/uploads/EIB-Report-on-Financial-Instruments-and-Social-Housing.pdf.[Accessed 3rd October 2015].

Goodbody (2015) Irish Housing Market: A detailed analysis. [Online] Available: http://www.finfacts.ie/biz10/Irish%20Housing%E2%80%93Goodbody_via_Finfacts.pdf [Accessed 28 September 2015].

Housing Agency (2015) National Statement of Housing Supply and Demand 2014 and Outlook for 2015-17. Housing Agency, Dublin.

Kearns, K. C. (2006) Dublin Tenement Life: An Oral History of the Dublin Slums. Gill & Macmillan Ltd.

Kelly. A TD Minister for the Environment, Community and Local Government (2014). In Environment, Community and Local Government. The Social Housing Strategy 2020: Support, Supply and Report. [Online]. Available: http://www.environ.ie/en/PublicationsDocuments/FileDownLoad,39622,en.pdf [Accessed 30th September].

Kenny J. 1973 Committee on the Price of Building, Dublin

Lorcan, S (2014) Renting in Ireland: The Social, Voluntary and Private Sectors

Meghen, P.G (2011) Building the Workhouses, In Chapter 2, Outline of the Development of the Irish Housing System[Online]. Available: http://www.nuigalway.ie/media/housinglawrightsandpolicy/Chapter-2-Outline-of-the-Development-of-the-Irish-Housing-System-Housing-Law,-Rights-and-Policy.pdf [Accessed 5th October 2015].

National Economic & Social Development office, Housing in Ireland: Performance and Policy Background Analysis. The demand for housing in Ireland. [Online] Available: http://files.nesc.ie/nesc_background_papers/NESC_112_bg_3.pdf. [Accessed 5th October 2015].

Norris, M. (2014) Policy drivers of the retreat and revival of private renting: Regulation, finance, taxes and subsidies. In Lorcan, S. Renting in Ireland: The Social, Voluntary and Private Sectors

O’Connor, N (2015) Housing crisis: Ireland needs five to 10 new Ballymun as soon as possible. Irish Times, 8th October

Redmond. D (2014) The private rented sector and rent supplement: The emergence and development of social housing. In Lorcan. S. Renting in Ireland:The Social, Voluntary and Private Sectors

The Irish Council for Social Housing (2012) Social Housing Newsletter: Budget 2012 Report. Impact on Social Housing [online] Available: http://www.icsh.ie/sites/default/files/attach/publication/385/socialhousing-winter2011.pdf [Accessed 1st October 2015]

White Paper (2011) Housing Progress and Prospects. In Chapter 2 Outline of the Development of the Irish Housing System [Online]. Available: http://www.nuigalway.ie/media/housinglawrightsandpolicy/Chapter-2-Outline-of-the-Development-of-the-Irish-Housing-System-Housing-Law,-Rights-and-Policy.pdf [Accessed 6th October 2015].

You have to be 100% sure of the quality of your product to give a money-back guarantee. This describes us perfectly. Make sure that this guarantee is totally transparent.

Read moreEach paper is composed from scratch, according to your instructions. It is then checked by our plagiarism-detection software. There is no gap where plagiarism could squeeze in.

Read moreThanks to our free revisions, there is no way for you to be unsatisfied. We will work on your paper until you are completely happy with the result.

Read moreYour email is safe, as we store it according to international data protection rules. Your bank details are secure, as we use only reliable payment systems.

Read moreBy sending us your money, you buy the service we provide. Check out our terms and conditions if you prefer business talks to be laid out in official language.

Read more