Literature Review Chapter

Foundations of Establishing Sustainable and Liveable Cities

The overall research seeks to determine the degree of social sustainability of higher density living, in cities in the Global South and the implications of spatial fragmentation. In order to do this, the research seeks to determine the relationship between urban form and spatial transformation in overcoming the history of social and spatial fragmentation. The research also seeks to determine the appropriate strategy that should be implemented by South African cities needed to achieve spatial transformation required to achieve social sustainability and liveability.

The literature review will provide an analysis of the social sustainability and liveability concepts as they have been theoretically debated. The scope of the literature review extends to the application of these concepts in the Global North. However, due to the lack of discussion and examples based on the Global South, the literature is used to identify the main models and key concepts that can be applied to determine the sustainability and cities in the Global South. The paradigms and key concepts will be selected based on the preliminary analysis of each model.

Furthermore, a brief discussion of the methodological approach will form part of the literature review. The comparative case study will discuss the historical grounding of social influences of cities in sub-Saharan Africa. The unique development characteristics of Johannesburg and Cape Town and South Africa’s political history, make these case studies an ideal example in the context of developing countries. This is particularly relevant to the establishment of cities and the social influences. This is further encouraged by the undertaking of preliminary fieldwork. Research methods such as observation, exploratory interviews and multisensory walking will be briefly outlined. There will be a separate chapter on the case studies, which will provide an in-depth analysis of both case studies. This chapter will provide an analysis of the changes over two periods in time, in order to provide a comprehensive understanding of the demographic and spatial transformation of both cities. The proposed periods include (1923 – 1943) and (1994 – 2014) due to the significance of these periods in South African history. The former is indicative of a period of spatial fragmentation and the latter is symbolic of the beginning of social and spatial transformation.

The sustainability concept was first introduced in the 1987 Brundtland Report which defined sustainability as “development which meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability for future generations to meet their own needs” (Littig and Grieẞler,2005:65). Both the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) 1987 Conference and the United Nations Rio Conference 1992 presented the pillars of sustainability as a combination of ecological, economic and social dimensions. While these dimensions are widely used, there is no universal definition for the concept. For the purpose of the study, the most appropriate definition is the one used by Goonetilleke et al., (2011) which states that sustainability is “about increasing the liveability of urban areas with improved quality of life and place, as well as a resilience towards foreseen and unforeseen external pressures” (p154). This definition provides a foundation of the conceptual analysis of the proposed models.

In both academic and international the discussions of sustainability there is often a geographical bias towards European cities having been selected to evaluate sustainability measures. The 2016 Sustainable Cities Index Report ranked 100 global cities according to the dimensions of sustainability, not surprisingly many the cities were located in Europe. The report, indicated that most European cities achieved higher scores than cities located on other continents. In terms of sub-Saharan Africa, Johannesburg and Cape Town ranked 90th and 95th respectively for both environmental and economic sustainability measures. With regards to the people index (social sustainability measures) Johannesburg ranked 99th and Cape Town 100th. This is not surprising as very few Global South cities made the list, yet still very alarming. As cities are fundamentally about people and very few cities ranked high on this measure. Which creates an alert as to the primary function of these citizens and the role of the people that occupy them.

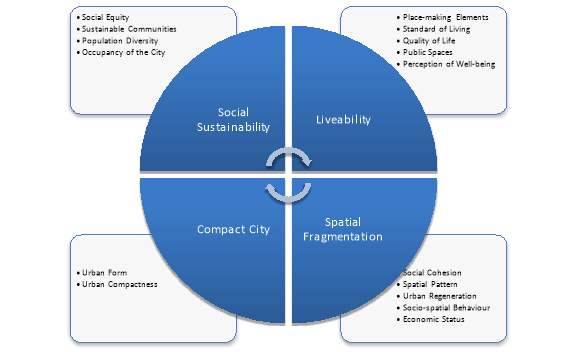

While sustainability comprises of three dimensions, due to the lack of literature focused on the social dimensions, this literature review will primarily focus on the social dimension and the key challenges associated with achieving socially sustainable development in cities. Considering this, the literature review will seek to determine, whether or not the compact city approach can be used effectively to aid spatial transformation. Furthermore, specific analysis of social sustainability, liveability, spatial fragmentation and compact city models will form the foundation of the proposed paradigms as illustrated in diagram 1 below.

Diagram 1: Proposed Paradigms of Sustainability and Liveable Cities

The combination of these models form a cyclical framework of the proposed paradigms needed to achieve socially sustainable and liveable cities. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 11 outlines that cities and human settlements should be “inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable”. The objective of the SDG 11 is to “enhance inclusive and sustainable urbanisation” with specific focus on communities in cities. As outlined in the 2014 State of African Cities Report “sustainable urban planning is necessary to eliminate the causes of segregation and exclusion” (Arcadis, 2016, p39). The framework is reviewed through the exploration of emerging issues associated with achieving spatial transformation. The framework will also be used to examine the compatibility of liveability and social sustainability in achieving sustainable higher density developments in cities in developing countries. Finally, it will also be used to determine the various actors responsible for achieving a sustainable city?

There is also a problem with a universal definition of social sustainability. In order to overcome this problem, Vallance et al. (2011) group social sustainability research focus into four categories, namely: “meeting basic needs and addressing under-development, changing the harmful behaviour of the affluent and promotion of stronger environmental ethics, maintaining or preserving preferred ways of living and protecting particular socio-cultural traditions” (p342). This summary is based on research conducted by Sachs (1999), Godschalk (2004) and Chiu (2002, 2003), who all highlight the importance of certain qualities required to maintain social sustainability. What the authors do not mention, is that collectively the research conducted primarily focused on social sustainability and the environment, as a solution to maintaining “traditions, practices, preferences and places people would like to see sustained or improved” (Vallance et al., 2011, p344). To an extent, these research areas may be of relevance, as the SDG 11 outlines that urban life has been influenced by “cognitive processes”. However, there exists the possibility of “changing of mind-sets in ways that profoundly influence social development” and therefore changing the practices once considered tradition.

The citizens that use the city should be considered as an extension of the city and a representation of the varying types of urban life that exist within it. With that the development of socio-cultural traditions and practices. In the context of sub-Saharan African countries, there is a lack of literature that explores the impact of social sustainability, on the development of urban densities and form. Although terms such as social cohesion, social capital and social exclusion and inclusion are used in relation to discussions of social sustainability. Nonetheless, these overlapping terms should be categorised according to the common characteristics related to human behaviour and experience of the people in it. As cities are places for people, Vallance et al. (2011) alludes to the overall human experience in terms of the “quality of life, social networks” and “living spaces and leisure opportunities” (p344), are neglected as an important aspect in urban development. Dempsey et al. (2012) emphasise the importance of determining the extent to which the compact city model and consequently density contribute towards social sustainability (p92). This may be an underlying warning to the appropriateness of the compact city model or perhaps a consideration of the desired social sustainability outcomes.

In terms of density and social sustainability can be this marginalisation solely in terms of the physical application. This application is examined in relation to the examined relationship between social equity and physical density and the relationship between sustainable communities and perceived density. According to Dave (2011), social equity enables access to services and opportunities, while sustainable communities determines the “attachment to community, social interaction and safety within the neighbourhood, perceived quality of the local environment, satisfaction with home, stability and particularly in collective civic activities” (p190). These elements can be used to measure the social sustainability of a given area although, it may not be a comprehensive indication of the social sustainability achieved. As not everyone will be happy with all the indicators or even feel included. This raises the question of whether it is better to aim for achieving a degree of social sustainability for the majority or rather focus on the minority who feel excluded from the intended purpose of social inclusion. This aspect may be considered in relation to the city function and achieving a ‘good city’.

Mallach (2014) discusses social cohesion as a dimension of the good city, which should reflect a degree of diversity amongst populations in terms of social, economic and racial classification. Furthermore, this diversity is reflected in the multiple functions of the city according to various entities and the people involved. Mallach (2014) has grouped these entities according to economic, social or demographic, physical and political functions. The economic function is primarily based on the economic success and availability of resources in the city, while the social or demographic function place emphasise on the people who live in the city, their specific connections and relationships. This function also includes those who occupy the city less frequently such as commuters and tourists. The physical function is based on the geographical spatial pattern of the city, the vitality of neighbourhoods and the quality of the environment. The last political function is concerned with the legally defined boundaries and the local government.

There are varying definitions and interpretations of the meaning of social sustainability. In general, the consensus is that social sustainability is more of a social matter rather than a spatial matter. This lack of a universal definition also contributes towards multiple overlapping concepts that are often used interchangeably. These include social cohesion, social capital and social exclusion and inclusion. The authors that use these terms so interchangeably provide no descriptive difference in the application of these terms. However, when applied to either the individual or the community they provide meanings of mobility and upliftment. The use of social cohesion refers to the community and the social interaction required to contribute towards a happy community. Social Capital on the other hand describes the assets that communities have, either tangible or intangible. These assets can be used to improve specific aspects of the community, more often this applies to the social aspects. Social exclusion and inclusion help to highlight those citizens that are marginalised based on accessibility. The use of this term can help address certain exclusionary practices and traditions in the community. The community and the individual are considered in terms of the impact that the development and the environment have on them rather than the impact that social behaviour will have on the environment. One can assume that because of the social and environmental link between the concepts that there would be more of a reciprocal relationship. This assumes that the responsibility of looking after the environment and preserving of socio-cultural traditions and preferences will be left to the community and individuals within it. The relationship between social sustainability and urban development is discussed more in terms of the social implications rather than the spatial implications. Reference is more often made towards the impact of density and compact city. The emphasises on social justice in relation to density is not explicitly discussed amongst any of the authors. One would assume that one of the key elements of social sustainability is social justice, however, this has not been proven by any of the academic readings. The final concept discussed was the ‘good city’ and the notion of the right to the city. Various elements are discussed in relation to this concept such as the diversity within a city, spatial boundaries and perceptions. This is the only concept discussed in the social sustainability model that considered spatial boundaries. This concept argues that at the centre of the ‘good city’ is the idea of a diverse community and with that a diversification of social, cultural and economic groups.

In summary, this model can be measured according to social equity, sustainable communities, population diversity and occupancy of the city. Social equity refers to the provision of access to services and opportunities that contribute towards the enhanced livelihoods of citizens within the city. Sustainable communities are assessed in terms of the attachment to the community, level of social interaction, neighbourhood safety, perceived quality of the local environment and the satisfaction with home, stability and civic activity. The population diversity is analysed by the social, economic and racial classification present within the city. Lastly, the occupancy within the city is measured by the number of people living in the city and those that occupy the city less frequently such as commuters and tourists.

Liveability is also often discussed in terms of the measure of the standard of living or the quality of life. Both these measures differ in terms of the primary focus. The standard of living is measured in terms of economic growth and the quality of life is linked to the experienced sense of wellbeing. Spaces that demonstrate the liveability of a city are often associated with physical amenities such as public spaces. There are a broad range of public spaces which include public squares, parks, municipal buildings, cultural sites, sporting arenas, leisure facilities, shopping areas and markets, roads and pavements. Other areas associated with liveability are cultural offerings, career opportunities, economic dynamism & degree of safety and public space. According to Kabir (2006), these spaces may also be described as “fortresses of freedom, spaces of action and islands of humanity” (p41). Even though these spaces encourage social interaction, they may still yield concerns of public safety in which citizen’s desire security in cities. These can lead to areas of exclusion due to the desired protection from either real or perceived fears. Lennard (2012) warns that “no city can overvalue the standard of living and undervalue the quality of life if they want to be socially sustainable” (p4). This point is further emphasised by Kabir (2006) who draws comparisons between urbanisation and the economic development of cities and the concerns it raises about sustainability. Furthermore, this impacts directly on the urban population as the author admits that “life in cities can reduce the wellbeing of some people”. The author does not elaborate further on the status of people that are affected, although one can assume that the vulnerable particularly the homeless and unemployed will be affected. The role of place making is emphasised in the “outcome of patterns of development”.

Even though the principal dimensions of liveability may be known, this paradigm also has no universal definition even though it is often discussed in relation to sustainability and infrastructure. It could be argued that in order to address the liveability of cities, focus should be on reducing automobile dependencies in cities through building more sustainable urban form and creating more liveable places. These places should encourage citizens to use the spaces provided by encouraging interaction and giving meaning to various spaces. This can be through the promotion of open festival spaces, market spaces or event an activity area. Place-making can be used in this regard. Place-making as a principal dimension of the liveability of cities, is the process of transforming space into place, giving identity, meaning and collective memory. Place-making is influenced through urban design and innovative city planning. However, while these may be easily suggested, Ling et al. (2006) suggest that the ideals of liveability are difficult to implement using place-making.

The City of Vancouver, Canada is often referred to as an example of one of the most liveable cities due to its establishment of a liveability agenda in 1976. In the case of Canada, the liveability ideals have mainly been integrated into downtown and infill development. However, the city development has been criticised for not providing equal access to opportunities and subsequently not addressing homelessness. Melbourne in Australia is another city that is referred to as an example of achieving a liveable city. However, in this case liveability is discussed in terms of class. Holden and Scerri (2013) points out that “for the inner city” the City Council carried a more undeveloped “sense of social justice in areas of jobs, housing and public services” (p445). Holden and Scerri (2013) proposes separating cities into three categories, namely: city of satisfied – experience liveability, city of disadvantage – not experiencing liveability and city of future – caught between both. The two examples of liveable cities both demonstrate strengths and weaknesses of the approach to establish liveable cities.

Ling et al. (2006) suggest that in order “to achieve sustainability and liveability, cities must address past challenges and to maintain, cities must address present and future challenges”. This is a very big task for any city especially in South Africa, where the legacy of apartheid spatial planning is still being addressed. The United Nations Human Settlements Programme (2014) pose a very relevant question “how can liveable, safe and prosperous urban locales be developed in Africa?”. Another point worth considering is that of Kenworthy (2006), who outlines that “changing the present unsustainable forms and patterns is a very challenging process”, perhaps the solution is not in simply changing unsustainable patterns but adapting them into more sustainable patterns. Possibly the answer is in determining the elements that contribute towards achieving these liveable, safe and prosperous urban locales as well as the individual study of African cities. This concept is linked closely to sustainability, which implies that improved urban liveability contributes towards sustainability.

However, criticisms of this paradigm include it being a prerequisite of infrastructure goals rather than a policy of participation and inclusive planning. This has been emphasised by various scholars, who have written about liveability in terms of infrastructure development. There is also the possibility of it not providing equal access or opportunities for all, as such not addressing social justice. Other examples include the unintended consequences of exclusion because of added security measures in public spaces. Either to address real or perceived fears by those that utilise the space.

The liveability model and the social sustainability model both have a lack of universal definition. This still poses a problem for the application and interpretation of this concept. This has clearly been demonstrated in the case of the cities of Vancouver and Melbourne, that have been referred to as examples of liveable cities. Both examples have demonstrated advantages and disadvantages of the model. However, one element that remains a constant, is that social exclusion cannot be totally ruled out. It is a by-product of city living that not all citizens will be included or have access to opportunities. This model has less to do with the social aspect of city living and more to do with the spatial development of spaces. This model contributes very little to the concern of social justice and establishing an inclusive and liveable city. This is evident in the undertaking of place-making which, primarily seeks to transform spaces into places that can be utilised and relatable to those that occupy the space. Place-making does not exist only for a certain period but can evolve with the transformation of cities. This is an important aspect in city living, as the urban lives within the city will constantly be evolving and thus the significance of traditions too. This does not override the preservation of socio-cultural traditions or the preservation of certain spaces. This is important in reserving the identity of specific spaces.

In terms of measuring the liveability of a city, place-making, standard of living, quality of life, public space and perception of well-being can be used as indicators. Place-making indicators include identifying those spaces that have been transformed, places with specific identities and places that contribute towards a specific meaning or hold a collective memory. The measure for the standard of living is informed primarily on the economic growth or status whereas the quality of life measure includes a sense of well-being. Other types of indicators include the types of public spaces available to those in the city and the perception of fears or crime.

Fragmentation is described as a spatial phenomenon rationalised by the segregated functions and classes which, has often been influenced by the development of separate residential and business locations. In the case of South Africa, there is a legacy of social and spatial fragmentation. Research conducted by the Gauteng City Regional Observatory (GCRO) has concluded that the impact of apartheid planning is still visibly present in Johannesburg that is often referred to as the apartheid city. The GCRO also have ongoing research which intends to understand the objective of the post-apartheid city. One of the guiding questions is “how do policy makers and users of urban spaces understand the undoing of the apartheid city?” (Ballard, 2016). The research alludes to the overcoming of historical fragmentation being more than a policy outcome but also a behavioural change. Cassiers and Kesteloot (2012) raise the question about whether segregation can be addressed by policies as either a challenge or a problem? The approach adopted should implement the “targeting of the exclusion mechanisms” rather than just assist the poor in selected areas (Anderson, 2006 cited in Cassiers and Kesteloot, 2012, p1915).

The development of urban regeneration policies is an example of policies that assist the poor in selected areas. Rodríguez et al. (2001) refer to the application of urban regeneration as a primary component of urban policy in Europe. In the city of Bilboa, Spain the spatial pattern of the Central Business District (CBD) was altered because of the decline of the manufacturing sector. In this case, urban regeneration was implemented to focus on coping with the consequences of restructuring, rather than managing city growth. Notably, the “1980s marked a decade of increasing concern with social justice and equity consideration in urban planning” (Rodríguez et al., 2001, p168) although this was not evident in the Global South, as no examples in this area have been mentioned.

The socio-spatial nexus of fragmentation is based on the social construct of segregation. In order to address the socio-spatial construct of segregation, there needs to be the possibility of spatial transformation. However, the State of African Cities Report 2014 highlights that “urban planning faces challenges of urban sprawl, housing backlogs, poverty and inequality, segregation and slum and informal settlement with the city centre” (p13). This suggests that in order to address concerns of spatial fragmentation, urban planning challenges should be addressed first as segregation forms part of these challenges. Furthermore, according to the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (2014) the “greatest challenge to urban politics in Africa is the inequality that characterises the ‘urban divide’, with the urban dwellers highly segregated by class and ethnicity” (p44). This statement is further supported by Cassiers and Kesteloot (2012), who consider segregation in terms of social cohesion. Social cohesion is defined as “the existence of different social and territorial groups present in the city” (p1910). The social construction of spaces is given different meanings by different groups through symbolism. According to Madanipour (1999) spatial behaviour “is an integral part of our social existence” (p879). The authors look at the influence of different socio-spatial structures on negotiating the processes between different social groups. They acknowledge that there are flaws amongst the way different social groups are treated. This is once again discussed in the context of Europe, as they point out that socio-spatial inequalities are on the rise. Although, Cassiers and Kesteloot (2012) admit that when compared to other continents “European cities still hold a strong local public power and an active civil society” (p1910).

These are also influenced by the pressure on cities to perform efficiently due to an increase in global competitiveness. This global competitiveness results in the rapid increase of social and spatial inequality. This is primarily seen through the social division of labour as the expanding financial sector is part of globalisation and particularly capitalism. The inequality is noticed by the division in economic status and the marginalisation of the rich from the poor. Other factors linked to economic status, is the accessibility to opportunities. The hypothesis that fragmentation rises and falls with distance is based on accessibility to economic opportunities. According to Cassiers and Kesteloot (2012), “segregation should not be reduced to the spatial separation of different ethnic groups” but “be characterised as spatial separateness” (p1912). In the case of cities, spatial segregation can result in the negotiating of different uses of space with different meanings. These can either result in i) an urban centre for the wealthy and the periphery for the poor or ii) an urban centre for the poor and the periphery for the wealthy. This is a possible outcome of the relation to distance and fragmentation. In the case of South Africa, both examples are demonstrated in Cape Town and Johannesburg respectively. This is further addressed by planning regulations, policies and infrastructure investments. This will be further elaborated on in the case study comparison section.

In summary, the spatial fragmentation model is primarily based on both the social and spatial fragmentation issues. Debates have centred on addressing both issues concerned with the spatial patterns and social segregation. Earlier debates in this section have referred to the segregated functions presumably in terms of land uses. Another reference has been made to the segregation of classes, namely seen in the social status difference between the rich and the poor. So far this seems to encompass aspects of both the social sustainability model and the liveability model. Specifically, in relation to the assessment of spatial behaviour and the role of urban regeneration. Urban regeneration has been proposed as a solution to addressing segregation. It remains to be decided whether segregation is viewed as a challenge or a problem. A problem assumes that there is an underlying cause that can be addressed to alleviate the problem. On the other hand, a challenge can refer to a gap in the present implementation methods in place. Depending on the specific point of view, policies can be developed that address concerns of spatial separateness. These can be assessed by the specific spatial patterns. The spatial pattern is dependent on the type of development in the inner city that influences the type of periphery development. This has a significant impact on the contribution towards inequality which has a significant link to the social construct of segregation. This is a strong theme from the spatial fragmentation model. Another significant link is the effect of global competitiveness of cities on the economic status of citizens and the accessibility to opportunities. To address spatial fragmentation, the following spatial transformation measures are proposed. These measures include social cohesion, spatial pattern, urban regeneration, socio-spatial behaviour and economic status.

Howley (2009) states that sustainable cities relate to an increase in the demand for travel and higher residential densities to reduce negative environmental impacts. The final model is the compact city, which is perceived to have benefits of greater accessibility and better social life opportunities. These include social inclusiveness, economic vitality, cultural attractiveness and environmental wellbeing. Salingaros (2006) states that while the compact city is essentially “a city for the people” (p109), the approach mixes shared civic spaces with concentrated arrangements of structures. These indicators are key to developing a walkable city. The development of a walkable city may be as a result of a city economic strategy. Although, Burton (2001) argues that the compact city model claim of social equity is the “least explored and the most ambiguous claim” (p2). Presumably, compact cities require the promotion of increased population densities which is a similar trait to the sustainable city. Contradictory to this though, is the limitation of population growth in order to achieve the ideals of liveability. As liveability is critical to the establishment of a sustainable community. Howley (2009) points out that there still remain questions about the liveability of compact cities. This may be due to the fact that the compact city model rarely addresses concerns of social issues which focus on the quality of life. The broad range of social justice issues remains a mystery as the relationship between the two has been under researched. The broader debates encourage higher urban densities which results in more productive economies and more vibrant and inclusive communities.

The connection between housing supply and resident population is influenced by the density comprising of two elements, namely: the physical structures and the actual resident population. However, Turok (2011) argues that a “density strategy should provide the means to shift the growth trajectory of a city in a more efficient, equitable and or sustainable direction” (p471). According to Salingaro (2006), there is nothing wrong with either higher or lower densities as long as it is well integrated. Density has both positive and negative impacts on achieving social sustainability. Although, most negative associations related to density are because of the perceptions of density. This is because the perceived density is based on the views of the community, whereas the physical density is based on calculations and ratios. These may extend to urban form as it includes the spatial layout, land uses, housing and building types, transportation infrastructure and density. Turok (2011) recommends justifying the intended purpose of using density as it is important to set priorities. Key considerations in setting priorities include i) determining who the city is for and ii) to what extent are public bodies willing to invest and regulate? This is important in considering the impact of car ownership and sprawl that counteract the aim of creating compactness.

Although advantages of the compact city include, better services and facilities, better public transport and an increased vibrant cultural life. There is limited research around “the claim that the compact city is socially equitable” (Burton, 2001, p2). This is especially true “in the context of developing countries, as very little is known about the social dimension of sustainability in relation to urban densities and form” (Dave, 2011, p189). Although, according to the State of African Cities Report 2014, “development corridors are promoted to geographically disperse both economic activity and populations” (United Nations Human Settlements Programme, 2014, p7). This indicates that urban geography is becoming more of a priority for African nations. The report has also mentioned that South Africa is one of the few countries in sub-Saharan Africa to have a growing urban majority. In the context of South Africa, the historic apartheid cities demonstrate both densified and sprawl city development. The United Nations Programme (2014) recommends changing regulations that have been inherited by colonialist urban planning regimes in order to promote urban sustainability. Since the democratic government election in 1994, urban integration and densification were identified as government objectives. This was implemented in the development of Spatial Development Frameworks at city level.

According to Gordon and Richardson (2007), there are different methods of implementing the compact city model, each with different planning implications in terms of the macro, the micro and the spatial structure approaches. The macro approach is centred on achieving high average densities at citywide and metropolitan level, whereas the micro approach focuses on developing high densities at neighbourhood or community level. The spatial structure approach centres on developing a pattern orientated to the downtown or the central city rather than a polycentric spatial pattern. This is the most appropriate method of implementation for the research being undertaken. These varying implementation methods are largely dependent on the spatial geographies of cities. Another aspect worth considering is the density versus high rise discussion. Although often discussed as interrelated concepts, high rise is discussed in relation to the compact city. Singapore has been referred to as a successful example of a compact city that demonstrates safety even though there are residential buildings of 50+ storeys. However, concerns about the social sustainability of these compact cities has been raised by Lennard (2012), in terms of the affect it has on young people.

According to Howley (2009), “problems such as crime, congestion and pollution are all prevalent in central cities … resulting in the migration of residents to the suburbs” (p793). This has been the result of Johannesburg, many residents left the city centre to purchase property in the suburbs. In order to alleviate these problems, indicators used should measure the effectiveness of urban compactness including density, mixed land uses and intensification. This approach has been criticised for contributing towards congestion and overcrowding as well as a lack of research addressing social issues, which focus on the quality of life. There is also a limitation in terms of the cost of living, lack of living space, transport related issues such as noise and pollution. Perhaps this is the downside to achieving vibrancy and vitality.

The overall compact city model is concerned with the effectiveness of developing higher density developments and increase high rise developments in cities. On one hand, the advantage is the contribution towards community diversification, vibrancy and the efficient use of public transportation. The disadvantage is the negative impact it has on the well-being of citizens in terms of health benefits, the increased noise pollution, the accessibility to opportunities and the lack of living space. However, despite the disadvantages it seems that African countries have adopted the model to encouraged citizens to better utilise the city. Development corridors have been used as an implementation tool for developing increased densities at multi-nodal points. Presently, there are conflicting views regarding the benefits of the compact city model. Both views, do little to address concerns of social justice, instead seem to worsen the effects of social justice. This is further evident by the indicators of urban form and urban compactness. Urban form indicators include spatial layout, land uses, housing types, transportation infrastructure and density. The final measure is urban compactness which includes indicators such as density, mixed land uses and intensification.

The models reviewed in the conceptual analysis vary greatly according to the primary focus. These range from extremely centred around social issues to those extremely focused on spatial issues. These extremes highlight areas of the limitations. The social sustainability model exhibits traits focused mainly on social issues with very limited reference to spatial issues. These are particularly focused on social justice, social equity and sustainable communities. On the other hand, liveability shifts focus on to more spatial issues and less about social issues. Areas of concern centre around the public space or realm, urban form and standard of living. There is a correlation between the focus on the standard of living and the quality of life, which is the only focus on the social issues. There is a strong focus on the link between the environment and the spatial form of the city. The spatial fragmentation model discusses both the spatial and social issues previously highlighted in the social sustainability and liveability models. Spatial fragmentation provides a socio-spatial link between spatial fragmentation, social segregation, inequality and urban integration. The last model is the compact city. There have been mixed debates about the appropriateness of implementing the compact city. However, concerns have been raised about the social benefits of higher density living in cities, the potential development of gentrification as a result of urban regeneration initiatives and the accessibility it provides. Considering the key features of all the models, the diagram overleaf summarises the measures for each of the proposed concepts. The overall diagram provides a foundation for the paradigms of achieving a socially sustainability and liveable city.

Diagram 2: Measures of Proposed Paradigms

The conceptual analysis seemed to answer the following questions i) what are the emerging issues associated with achieving spatial transformation, ii) what is the compatibility of social sustainability and liveability achieving sustainable higher density development and iii) who are the various actors involved in achieving a sustainable city?

The emerging issues that were highlighted in achieving spatial transformation include addressing inequality, accessibility to opportunities, spatial fragmentation and the growing gap between the social status. Addressing inequality requires addressing the challenges associated with urban planning, which has been mentioned as one of the problems facing planning. The challenge of providing opportunities to all citizens through accessibility still remains a challenge in terms of overcoming issues of social justice. These emerging problems are directly linked to issues associated with spatial fragmentation, often inherited from colonialist planning systems. This inherited spatial problem has also resulted in the social divide between citizens of differing economic status levels. This is further enhanced by the globalisation of cities.

The compatibility of social sustainability and liveability in achieving a sustainable higher density development, which is put into question by the conceptual analysis. This is due to the contradicting views of the liveability model as some of the disadvantages are contradictory to the aims of social sustainability. Liveability lacks in addressing effects of homelessness, providing accessibility to all and addressing issues of social justice. On the other hand, the compatibility of place-making principles seems to contribute towards transforming space into place. Notably, both models have no universal definition which is problematic in the application of the models as well as the interpretation of the model by various agencies.

The studies reviewed briefly mention various actors involved in achieving a sustainable city. These include using an interdisciplinary approach which involves citizens, the local authority and private or public planners. Involving citizens provides a grounded approach to any model implemented which often results in a bottom up approach. The involvement of the local authority extends to government agencies as well. They are often responsible for the implementation and decision making. The role of the planners is to establish strategic plans and select focus areas. This is often the trap when applying the compact city model which selects areas of interest based on assisting poor people rather than empowering them. The studies often referred to the models at international scale which could be applied more universally. For a more detailed or specific application at national, local or neighbourhood level requires individual case studies.

In conclusion while the social sustainability, liveability, spatial fragmentation and compact city models have been discussed, the most appropriate model to answer the research questions is spatial fragmentation. It discusses both social and spatial issues more suited to achieving social sustainability. The analysis of the four models provided a conceptual exploration of the strengths and weaknesses and will highlight the most appropriate model used to conduct the research. The following section provides an overview of the methodological approach.

The methodological approach considers the conceptual analysis as well as the preliminary analysis of the case studies. This preliminary analysis focuses on the social grounding of issues caused because of the establishment of both Johannesburg and Cape Town. Therefore, this analysis will provide a historical account that stretches back to the colonialism period and the apartheid era. This includes an analysis of the significant policies that influenced the social and spatial development in both cities. An in-depth analysis of the case studies will be provided in a separate chapter that will look at a closer comparison of the social and demographic change between the periods of (1923 – 1943) and (1994 – 2014) due to the significance of these periods in South African history.

The African continent is the least urbanised in the Global South and has limited research exploring the development of cities. According to van der Merwe (2004) “the continent provides a unique case for studying urban forms due to the variety of city structure influences” (p45). These include European, Colonial, Indigenous, Dual and Apartheid influences. These urban forms represent a period of the importation of the idea of urban living, as indigenous people lived off the land in tribal communities. However, these urban forms also contribute towards the negative factors that necessitate a differential look at the continent. Other factors include the rate of urban development and the population growth, the mismanagement of cities and sustainability of cities especially in terms of addressing poverty, social disorders and reducing the dependency on exports of primary products. Therefore, there is a need for African cities to “rethink what constitutes a ‘city’ since the Western concept is no longer applicable” (United Nations Human Settlements Programme, 2014, p37). Cities have evolved to not only being the centre of activity but also include concepts such as the satellite city. However, as Nicks (2003) points out that limited attention is given to the “implications of distance and time, particularly for low income groups” (p184). The satellite cities according to the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (2014) are being established to guide population pressure away from the capitals yet it does not consider the effect of these cities on low income earners that need to commute to the city centre. The establishment of satellite cities is influenced by the fact that available land within the city centre are normally sold to the highest bidder, which results in “lower-middle and low-income housing to the urban periphery where land prices are lower” (Nicks, 2003, p184). Furthermore, as people are the most important participants, their experience living in new environments is influenced by the urban form implemented. To counter act the negative effects, consideration of the role of urban design should be given to urban form. The implementation of urban design can be used to mediate the bringing together of urban activities including physical, spatial, social economic, symbolic and spiritual. There are general discussions around urban spatial theories, which discuss satellite cities, compact cities and corridor cities. Numerous scholars have referred to the rapid population growth within the continent which, contributes towards uncontrolled urban sprawl, increased poverty, social problems and lack of attracting economic investment (Arku, 2009; Mosha, 2001; van der Merwe, 2004). The compact city and corridor city are recommended as sustainable spatial theories that can be used to address urban sprawl. The compact city this is a way of expanding the city and public transportation. The corridor city encourages population growth from within the CBD towards existing radial links. However, in South African cities, property prices seem to increase with the distance from the city centre. The authors conclude that sustainable development is long overdue in South African cities and should “combine the corridor approach and the compact city approach” (Vanderschuren and Galaria, 2003, p275). Furthermore, Turok (2011) is in favour of residential densification and considers it important in South Africa because of the colonial and apartheid legacy. The author alludes to densification addressing sprawl, fragmentation and racially divided cities, in line with the compact city and corridor city urban theories. The successful implementation of a density strategy requires the shift in growth trajectory into a more efficient, equitable and sustainable direction. This is complimentary to the assumption that higher urban densities result in more vibrant and inclusive communities. This lack of investment has resulted in the disintegration of public transportation which is critical in achieving sustainable infrastructure and providing alternative transport options in areas of overcrowding. Vanderschuren and Galaria (2003) suggest that the separation of transport and settlement planning has resulted in the lack of accessibility in cities. In the State of the African Cities Report commissioned by the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (2014), states that the inequality according to class and ethnicity amongst, urban populations is a major challenge to politics in Africa. In order to overcome this and many other challenges of urban development, Arku (2009) suggests that political will is required to “pass growth management legislation that protect environmentally sensitive areas, reduce urban sprawl and improve quality of life” (p264). This suggestion infers that the lack of planning in African cities could have been avoided along with the economic and social problems associated with it.

While globalisation serves a greater purpose that “enriches the integration of socio-cultural, political and economic life in a post-modern world”, Van der Merwe (2004) refers to is as a “complex set of related processes” (p36). This has resulted in the focus of globalisation studies favouring Western examples of “world city hierarchies” which are defined according to financial, manufacturing, transport and cultural centre roles. Many of these attributes are not associated with African countries, this is further supports by Van der Merwe (2004) account that the African continent has the fewest world cities defined according to the above mentioned centre roles. Exceptions are in the case of two cities in South Africa namely, Johannesburg and Cape Town which are regularly referred to as global African cities. However, Cape Town has a secondary world city status when compared to Johannesburg. Africa is an ever-evolving continent that poses so much untapped potential that is often overlooked due to the history of spatial and social change. A study conducted by Chipkin and Meny-Gibert (2013) identified sites if social change in South Africa. The change was identified as both descriptive and analytical. The descriptive spaces were those “arisen” since 1994 and have been referred to as new spaces. Whereas analytical spaces include both new and more new sites. The authors explain that analytical spaces are “site in South Africa where people and things combine and relate historically in unprecedented ways” (p154). Although these spaces are of little significance unless they are occupied by the people that they are meant for. This is partially the reason why the placing of objects and materials are positioned to attract the attention of potential users of the space. (Boyer et al., 2012, p51) points out that the buildings during apartheid “often had an awkward fit with their sites, in part because of the distancing between the act of design and the context of the building” (p142). If cities are planned in a sustainable manner then the spatial transformation that is so often referred to in the Global North can be applied to African cities. Currently there is “no universal answer and no model for a sustainable African city” (Local Agenda, 2002, p2 cited in Donaldson, 2001, p3). According to Boyer et al. (2012) sustainability is “fundamentally a political rather than a technological or design problem” (p53). The following are assumed preconditions for achieving sustainable urban lives:

Cities play a key role in sustainable development as well as providing a physical structure which comprises design, function and the built form (McCormick et al.,2013). The origin of cities varies greatly across different continents and the function has influenced the role of citizens according to a number of factors such as status, wealth and political affiliations. O’Connor (1983) points out that “cities form critical links in every country between the population as a whole and the outside world” (p16). Therefore, to achieve sustainable development, the concept must be viewed holistically and applied to different city departments. There is an assumption that “African cities are in a permanent state of crisis as a result are largely marked by almost unfathomable levels of deprivation, cruelty, routine dispossession, and … marginal possibility of slight improvement” (Boyer et al., 2012, p51). On the whole, African cities present diverse ethnic and racial groups. This feature is considered an advantage as it “forms the meeting point of different cultures” (O’Connor, 1983, p99). Most African countries provide distinct ethnic divisions more than they reflect racial divisions. These types of divisions are more prevalent in South Africa. The apartheid city was contradictory to the aim of sustainability, particularly social sustainability. Furthermore, Goonetilleke et al. (2011) encourages the incorporation of sustainable development into urban planning as the lack of sustainable urban transformation initiatives which still remains a “challenge facing modern urban settlements” (p152).

South Africa is located in sub-Saharan Africa and is considered to be the most urbanised and developed country in Africa. The country has a population of approximately 55.9 million people according to Stats SA. According to the State of African Cities Report 2014, South Africa is among the cities that are experiencing sustainable growth (United Nations Human Settlements Programme, 2014). The country has undergone numerous city transformations from colonialism to apartheid and finally democracy. These transformations have continuously altered the social connections between citizens in both space and time. These transformations were enhanced by the policy formulation phases during the 1990s. These include i) policy formulation in line with global trends, ii) reconciliation which resulted in the desegregation of society in all spheres and iii) reconstruction through the development and upliftment of underdeveloped and disadvantaged areas. Donaldson (2001), confirms that there have been attempts to recreate the place and space of South African city identities. Planners, department managers and politicians responsible for urban development initiatives have been tasked with “reconstructing the impression of a spatially segregated urban society” (Donaldson, 2001, p1). One of the most visible attempts is the Johannesburg Council’s vision to develop the city into a “World Class African City”. Boyer et al. (2012) points out that “most cities in the global South fall into the trap whereby they define their priorities in terms of what they need to do to become ‘world class’ and ‘competitive’” (p58). South Africa is no exception to this as the City of Johannesburg have fallen into this trap. The research will analyse the implications of urban planning during apartheid, which enforced racial and social segregation. The research is underpinned by the need to understand the social (un)sustainability in the central city of Johannesburg. The investigation of the historical grounding/origins of social problems, will assist with determining the relationship between social segregation and spatial fragmentation.

The debate about the origins of segregation dates to the nineteenth century and the policies of the British colonial administration. It was only in 1914 when a formal political policy of segregation was implemented by the Labour Party. Interestingly, the Labour Party comprised of mainly skilled British mine workers and no Afrikaaners even though they supported the British administration. In 1924, General Hertzog of the National Party claimed that Afrikaaners were the “pioneers of South African civilisation” (p11). Chapman (2015) concludes that “spatial apartheid only really gained significant momentum sometime after the National Party won its first election in 1948” (p95). “Although central government was instituted under the Union, regional variations continued to exist. The Cape for example retained the right to have a non-racial franchise based on property rights, whereas in other regions black political rights were upheld” (Deegan, 2011, p3). In addition to the formal segregation policy, the Population Registration Act, 1950 was implemented to officially racially classify groups according to white, coloured, black, asian/indian. This classification and many others has resulted in ethnicity being a “sensitive subject and academic writes as well as politicians and census-takers, are sometimes reluctant to give explicit attention to it” (O’Connor, 1983, p99).

Arku (2009) alludes to the requirement of political influence to change the existing forms of urban development through growth management legislation such as the smart growth approach. This approach addresses unpleasant urban development patterns through encouraging compact, diverse and walkable developments. Even though there are a limited urban study focusing on compact cities in South Africa. The responsibility to reorganise the urban society often lies with planners, managers and politicians. South Africa has undergone numerous city structures from colonialism to apartheid and finally democracy.

South Africa is still addressing the legacy of apartheid and the spatial fragmentation that has physically and socially divided many residents. Through strict control measures of territorial segregation enforced through forcible relocations of families out of racially diverse areas that were located close to areas classified white areas. This mainly due to the Group Areas Act, 1950 which, justified compulsory zoning of all urban areas into exclusive group areas. One aspect of apartheid that is very rarely mentioned is the fact that is forced a class mix in what was classified non-white areas. The most notable segregation policy is the Urban Areas Act, 1923 which empowered the local authorities to establish separate townships for African residents (Morris, 1998, p760). Another piece of influential laws was the Pass Laws which controlled the movement of black residents specifically. These residents were required to carry around a ‘pass book’ which stipulated whether residents were permitted to travel and live within the city centre. Furthermore, these laws determined in which urban areas an individual can live in. Morris (2004) argues that South African cities continue to reflect the spatial fragmentation encouraged through apartheid planning these further extend to the socio-economic order as well. This could be as a result of race being a determining factor of income and employment. Due to this the author is sceptical at the possibility of establishing a “socially just city”. My research seeks to disprove this scepticism. The “extended spatial patterns characteristic of the apartheid city” (Ballard, 2016, p2). In order to address this, it is recommended that “sustainable urban planning is necessary to eliminate the causes of segregation and exclusion” (United Nations Human Settlements Programme, 2014, p39). South African cities are characterised by low density sprawl, fragmentation and separation. These are largely seen in the long commuting distancing and the work travel patterns. Theoretically we can assume that corridor development can create purposeful interaction that requires high-density development. This contributes towards addressing fragmented urban spatial setting imposed in the apartheid city. Relevant legislation that attempts to address the dysfunctional structure of South African cities include the National Development Plan Vision 2030 and Corridor Development Strategies and Growth and Development Plans for both cities.

Post-apartheid has resulted in more freedom of a racial and social mixing. When questioned about personal identity, answers usually include racial, ethnic, religious, linguistic, national and gender categories. According to Morris (1998), “as the black middle class grows, the deracialisation of the suburbs is intensifying” (p764). This is due to the history of relocation of white residents from the inner city outward towards the suburbs. However, this new-found freedom does not necessarily mean that people will welcome the new change with relocating. There will be a required societal reintegration process after enforced physical separation. Morris (1998) concludes that “most people will continue to live in uni-racial neighbourhoods that are in line with their apartheid racial category for the foreseeable future” (p770). The relocation to the northern suburbs was predominantly for the high-income earners. Although, the high crime level has resulted in the changing of architecture in “wealthy” areas by increased wall heights, sophisticated security systems, limited interaction with neighbours and public spaces considered “no-go” areas. Due to the social history of South Africa, Deegan (2011) considers a person’s ‘quality of life’ of interest because of the “years in which education, life chances and resources were allocated based on race” (p260). As such the author points out that there is a correlation between four categories, namely: economic status, racial group, happiness and life satisfaction responses. Thus, the difference in incomes between various groups is a limiting factor to change, especially in the context of South Africa. According to Donaldson (2006) the “South African city remains an interesting laboratory to explore how a society is grappling with its segregated past” (p351).

Johannesburg is located in the Highveld and has a population of approximately 4.4 million people (Stats SA). Historically, Johannesburg began as a gold mining town due to the discovery of gold in 1886. The town rapidly developed and became the central location for thriving economic institutions in the country and resulted in an economic boom. The boom resulted in the reliance of migrant black labour from outside the city into the central city. According to Deegan (2011), this was the beginning of low-cost labour which was “essential to maintaining profit margins”. Without this migration, the newly developed economic hub would not have been sustained. Parnell (2003) points out that in order for Johannesburg to succeed economically, the local authority realised the need for accommodating a racially diverse population. As such rather than implemented the already national policy of segregation at a local scale, poor non-white workers were housed in the inner city in order to maximise production efficiency. This resulted in the local authority providing “housing for a multi-racial working class” during the first decades of the twentieth century (Parnell, 2003, p616). However, this was soon coming to an end due to the Native Urban Areas Act, 1923 forced the Local Council to overturn “its earlier strategy of condoning African settlement in the inner city” (Parnell, 2003, p616). In 1933 Johannesburg inner-city was declared a “white-only are” under the Native Urban Areas Act, 1923. This was problematic as the demand for shelter increased due to the growth of the economic centre. This resulted in the practice of renting rooms in yards, even without permits. This contributed towards the racial division, white dominance and the divisions in class. Within this period, Johannesburg achieved the status of “the largest urban centre in Africa south of the equator” and the “economic hub of South Africa” during a time when the mining industry was new (Harrison and Zack, 2012).

During 1923, the municipality approved the Native Urban Areas Act which prevented non-white South Africans from purchasing or leasing property in white suburbs, including racial zoning laws that imposed racial segregation (Harrison and Zack, 2012). During the rapid development of the city, physical planning was implemented by town planning officials as an absolute with the specific purpose to racially divide residents. This resulted in the relocation of residents into racially allocated townships. This method of racial segregation was initiated by the Johannesburg local authority prior to the National Party implementing apartheid. The city of Johannesburg has been viewed as a city of “uitlanders” or foreigners. This term was introduced by the Afrikaaners to describe the British occupants in the city, since the establishment of Johannesburg. The Group Areas Act, 1950 further enforced the separation of land use functions and spatial fragmentation. The spatial development of the city was such that, the inner city was the centre of economic activity and home to white South Africans. Non-white South Africans were permitted to travel in the city to work but were prevented from living and socialising in the city. Hoogendoorn and Gregory (2016) agree that the “introduction of the Group Areas Act, 1950 and its amendments, which had more far-reaching effects on the socio-economic development of South Africa’s cities” (p403). The northern suburbs were home to the elite and wealthy white South Africans, where large plots and houses were built. Areas to the North and North-East of the inner city, produced economic growth among the well-off and was the selected area for the main international airport. The areas to the South and South-East of the inner city developed rapidly as low income settlements, were the sites for the relocation of forced removals and were poorly serviced informal settlements. While the development of apartheid caused effects that are still experienced twenty-four years in democracy, Parnell (2003) admits that there was a “complicated process by which the practice of urban segregation evolved in South Africa” (p636).

The inner-city landscape has undergone several image evolutions, according to Bremner (2000), these range from Western Modernity, Fin de Siècle European style, the Boer War monumental imperial buildings and finally British Edwardianism. Whether these evolutionary phases can still be seen within the city centre is yet to be proven through analysis of the existing building forms. The inner city seems to be a melting pot of urban form styles and seems to be an exhibition of the different images that can exist within a city. So much so that it is possible to have spaces spatially defined by different ethnic groups. According to Tomlinson et al. (2005) the city must be reimagined in ways that both remember the past and resist the modernist logics of states (p12). This is largely due to the different ways in which the city has been occupied in the psyche of non-white South Africans. Tomlinson et al. (2005) accounts for three differences firstly, the history of the city in terms of opportunities and employment, secondly the city represented a place of oppression and thirdly the segregated laws made the city a forbidden place. King and Flynn (2012) state that Johannesburg lacks the traditional attractions, its tourism appeal emerges from the urban fabric and is aimed at people who would be in the city for reasons other than site-seeing, such as business or visiting family” (p74). The study of heritage development could be to blame for this lack of interest as these types of studies primarily concentrate on Cape Town and neglect other cities.

The decline of the inner city began from 1980 until 1991 which, resulted in many business headquarters relocating to the northern suburbs. During 1990, the Johannesburg local authority implemented economic development initiatives to “reinvent, re-imagine and reformulate” the inner-city scene. To achieve this, there is a need for nation building but without city building this will be a wasted experience. However, by 1997 many of the city’s retail spaces were in the suburbs. Problems within the inner-city were assumed to be a result of crime and the mismanagement of the city by local government. As a result, business improvement districts were proposed as a strategy for regaining control of the streets.

Post-apartheid the inner city has since transformed and accommodated migrant jobseekers and an increase in informal economic activity. However, many migrants are poor. The inner-city regeneration strategy has the possibility of resulting in further social and spatial exclusion of the poor inner city residents. Winkler (2009) concludes that the “City of Johannesburg’s current regeneration practices and policies stand to benefit only the new urban elite, while prolonging the global age of gentrification” (p377). This is due to the impact of regeneration policy practices that relocate the poor to the periphery which results in exclusionary displacement. While the intention is to “rebrand” the inner city as a “cultural capital” in line with global city status, Winkler (2009) accounts for “significant inward migration of jobseekers” and an increase in the development of informal economic activity. The redevelopment of the city into a cultural capital can only be successfully achieved when “its residents also identify with it and feel a moral attachment” (Tomlinson et al., 2005, p1). Bearing in mind that “urban regeneration initiatives lives in changing perceptions about the areas that are economically depressed and feared” (Raco, 2003 cited in Hoogendoorn and Gregory, 2016, p409).

Due to the various cultures amongst residents, these groups may experience the city differently. Simone (2004) further supports this point by confirming that “particular spaces are linked to specific identities, functions, lifestyles and properties” (p407). Winkler (2009) also points out that there is a large majority of existing inner city residents that are poor. Even though the urban regeneration includes social cohesion and social mix strategies, this initiative may still lead to the social and spatial exclusion of these residents. The emergence of a central African ghetto image has scared tourists away from the inner city for fear of crime and safety. This is due to a focus on economic strategies rather than social policies. Literature also constantly makes comparisons between Johannesburg and American Cities, because desegregation has extensively been studied in the USA. Simone (2004) states that “many of the economic and political mechanisms that produced American inner-city ghettos have been at work in Johannesburg and these are only reinforced by the strong influence of the United States urban policy on South Africa” (424). The comparisons do not consider the difference in demographic and economic pressures between the countries. The no-white population is a minority group in America and in South Africa the non-white population is a majority group. The desegregation on this level needs to be at a macro scale. Authors such as Christopher (2001) have examined the extent to which desegregation has taken place since the democratic elections in 1994. Since the democratic elections in 1994, the local authority implemented economic development initiatives aimed to creatively change the image of the city into a “World Class African City” (City of Johannesburg, 2011). With this change, we can also expect a shift in the “use of the city”, until desegregation has successfully been implemented, this new use is largely unknown. Johannesburg Council still has a long way to go to eliminating the effected of racial segregation. Authors such as Chapman (2015) still feel that while segregation policies are no longer implemented, the effects are still felt.

According to Frenzel (2014) slum tours has been implemented as a means of promoting areas that are considered less desirable. The history of slum tourism dates to the apartheid period when ministers and government officials were taken around townships in order to meet a particular quota. More recently slum tours have been extended to inner city neighbourhoods in areas that are considered “no-go” areas such as Hillbrow and Yeoville. This may be due to the “social and spatial degeneration and urban grime found in the in the city” (Manase, 2005, p125). The author confirms that “walking tours aim at opening up South Africans to the beauty of the inner-city life” (Frenzel, 2014, p440). This conclusion makes you wonder why South Africans should be reminded of the beauty of city life when the experience of the past was only legally available to a minority. This minority experienced what Simone (2004) terms a “cosmopolitan, European city in Africa”. These areas were once considered elite white only areas in the inner city during the apartheid period. However, since the mid-1970s there was in increase in the movement of non-white residents into these neighbourhoods, the influx of these residents prior to the abolishment of the Group Areas Act in 1991 resulted in white flight. This is where white residents fled from the inner city to areas outside of the city centre in the suburbs. This relocation to the suburbs provided easier access to high quality schools and facilities. Another striking yet unsurprising conclusion is that the tours attract international visitors rather than locals that live in the country. In an effort to attract residents back into the city centre strategies have been implemented that promote the cultural quarters of the city. However, neither Hillbrow nor Yeoville have yet to be redeveloped according to this. Areas part of this strategy include Newton Cultural Precinct, Maboneng District and Braamfontein. These cultural precincts are considered safe nodes and have emerged as popular areas even though they are located on the fringe of the city. This resulted in the altered racial composition of the inner-city according to Morris (1994). Simone (2004) recommends the use of social infrastructure as it “is capable to facilitating the intersection of socialites so that expanded spaces of economic and cultural operation become available to residents of limited means” (p407). Much like walking tours provide an experience of city life, the notion of social infrastructure can be linked directly to the everyday activities of people within the city. Complimentary to the walking tours are “instawalks” which are walks in different urban and rural spaces, these are organised by key role players in the Instagram community. This method can be used to explore the movements, behaviours and perceptions of those that organise and take part in the walks. Graham and James (2007) argues that driving through the city can be as beneficial as walking through the city, yet this aspect is often overlooked and not considered an important part of social and cultural representation in Johannesburg.

Johannesburg displays efforts of corridor development from the link between Johannesburg to Pretoria. Most notably is the rapid rail link, referred to as the Gautrain, that has been developed around three anchor stations. One in Johannesburg CBD, one in Pretoria CBD and the last one at OR Tambo International Airport. The development in the CBDs is part of a national government urban sprawl strategy, aimed at inner city redevelopment. The most recent corridor development strategy is the Corridors of Freedom which intends to re-stitch the city to create a new further through the development of land adjacent to Bus Rapid Transit routes.

Cape Town is a coastal city located at the south-western tip of South Africa. Cape Town is well known for unique landmarks such as Table Mountain and Lions Head Peak. According to Statistics South Africa (Stats SA), Cape Town has a population of approximately 3.7 million people. Scott (1955) confirms that Cape Town is “ranked among the oldest permanent white settlements in the southern hemisphere”. Not surprising as Cape Town was discovered by Jan van Riebeck of the Dutch East India Company in the 1600s. It was during this time that is was “established as a way station in the mid-1600s to provide fresh produce to passing ships” (Gibb, 2007, p540). Worden (1992) confirms that Cape Town became the “gateway to Africa”, as it was the main harbour for ships to off load cargo and purchase fresh produce before proceeding further. It was only in the nineteenth century when the British settled in the Cape, that the Victoria and Alfred Basin located in the Table Bay harbour, became “the centre of Cape Town’s shipping trade”. According to Bickford-Smith (1995), the city of Cape Town “has a reputation of having a history of racial tolerance before apartheid” (p63). Due to the multi-storeyed and multifunctional buildings in central Cape Town, there is no unmistakable evidence that confirms Cape Town was segregated. The author accounts for the population of Greater Cape Town in 1951 to have totalled 632 987 comprising of 42.21% Europeans, 39.35% Cape Coloureds, 9.46% Africans, 7.67% Cape Malays and 1.3% Asiatics. The composition of the population in Cape Town has been described as unique in South African terms due to Coloureds comprising more than half of the resident population. This is presumably prior to the implementation of segregation during British colonialism and racial segregation during apartheid. When apartheid was implemented, racial segregation was enforced in schools, hospitals, churches and prisons.

The redevelopment of the Victoria and Albert Basin only occurred after 1980, when the area was cut off from the centre of Cape Town. In the mid-1980s the council decided that tourism was the most desirable option for Cape Town, as it would attract investment. The city was only known for shipping trade unlike Johannesburg which was established as an industrial economic centre. The Victoria and Albert Waterfront was redeveloped into “Cape Town’s prime tourist venue” and became one of the most publicised private investment commercial developments. This form of privatised public property was criticised for alienating “restauranteurs, small scale tourist enterprises and fisherman” (Worden, 1992, p8). The authors investigation into the heritage representation of the historic development of the Waterfront, paints a picture of British occupancy “as a more fitting element of Capetonian past” (p13). This account of the history of the harbour excludes contributions towards development, such as the “sailors, soldiers, slaves, Khoi, political exiles and fishermen who crowded the harbour before” (Worden, 1992, p13). During the development of the Victoria and Albert Basin, convicted labourers were employed to carry out work, yet their contribution is not remembered in the heritage account of the Waterfront. The exclusionary contribution towards heritage development “perpetuates the myth of the apartheid tradition that Africans formed no part of the Western Cape” (Worden, 1992, p17). The author concludes that the Cape Town Waterfront “is predominantly patronised by the middle classes”, further demonstrating the exclusion of the lower classes from what was developed as a tourist venue. While the Waterfront was developed as a local identity rather than a national identity, it does not represent the actual local identity representative of all Capetonians, residents of Cape Town.